Archive for the ‘The West’ Category

A bad ‘hair-ball’ day….!

Every once in awhile, I make a serious mistake and drive badly. With my good friend Kevin Denley in the passenger seat driving into Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary on Aug. 15th. 2016, I did not see a huge ditch by the side of the road and ended up falling into said ditch with my truck lying on it’s side. The passenger window was completely shattered and the whole left side of my truck was bashed in. Everything in the truck was on that side with Kevin wedged down. I was absolutely dumbfounded. We were stuck badly and it took some serious effort for Kevin to climb over me as I could not lift my door to get out. If I had been alone, I would have been in serious trouble. We finally climbed out and took stock.

Luckily, a ranger on a motorbike came along and I was able to get to the nearest village (20 kilometers away) to arrange a tractor (5 hour round trip) in order to pull us out. It took some time but we finally got up on 4-wheels. Luckily, neither of us were hurt but my pride took a beating. It was late at night by the time we got back to civilization, some food and a hotel with a hot shower. All I can say is: it was a bad ‘hair-ball’ day…!!

When it rains tapir, it pours tapir…!

A rare late afternoon capture of an Asian tapir Tapris indicus

A female tapir at a mineral hot spring in the Western Forest Complex of Thailand…!

Recently (Nov. 2014), I caught a female tapir that looked pregnant on my Canon 400D trail cam down in Southern Thailand at Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary located in Surat Thani province far off the beaten track.

First shot coming down the hill …!

The site is 60 kilometers by boat into the protected area. I got some really nice shots of the odd-toed ungulate as it moved along a wildlife trail on a ridgeline down to the reservoir. Also got a beautiful clouded leopard even though it was a bit out of frame. I counted my lucky stars…!

I have named this old girl ‘White Spot’ seen on her right shoulder…!

Then, I went back to Bangkok for some rest and after a few days, decided to go into my favorite protected area in the ‘Western Forest Complex’ to check and set-up a couple trail cams, and to sit in a photo blind where I got a black leopard 16 years ago, and then again in 2013.

What a pose with her rear leg extended just like a pedigree dog…!

I recently missed a black cat here when my Nikon 400 ƒ2.8 lens went on the blink in November last year. In 2010, I camera trapped a tapir in the morning just down from the blind. It has been a marvelous place and I have caught many species of Asian wildlife through the lens and by camera trap that come to the hot spring.

She must have heard me rustling in the leaves…!

As I was setting up my Canon 400D trail cam below the photo-blind, I got a bit frustrated as the camera would not trip after setup and so I left it. I was only 15 meters away from the blind. Somehow, I had nudged the control button to ‘Auto’ as I was to find out the next day.

And she high-tailed back up the hill but stopped short and came back down…!

I got five-steps, and there stood a female tapir out in the open coming down the hill to the hot spring. As I always carry a Nikon D7000 and a 70-300mm VR lens, I immediately started shooting.

Making her way back down to the mineral hot spring…!

I was also out in the open but as she looked the other way, I moved a little bit closer to get to my big lens (Nikon D3s and 200-400mm VR II) sitting on a tripod ready for action.

Still has not seen me…!

Tapir have very poor eyesight but hearing and smell are good. She must have heard me as she bolted back up the hill. She stopped short and then came back down. I was still shooting with the D7000. I finally got into the blind and started shooting the big camera. It was very exciting to see this odd-toed ungulate as they are nocturnal for the most part and hardly ever seen in the day.

A female for sure and a large wound on her rump: maybe a tiger or leopard, or wild dogs…!

I know of someone who has spent many years trying to photograph this species with no luck. He once spent 10 days at this hide unsuccessfully and then at another location for eight days. He left the sanctuary in despair and has been chasing them ever since..!

The moral of this story: Have a camera over your shoulder at all times if you are in the forest working or traveling through. You never know when something might pop out…I learned this from a National Geographic staff photographer (William ‘Bill’ Albert Allard) when he was here in Thailand as we chased down domestic elephants for a story in N.G. magazine…!

He said: “if you don’t have a camera, you aren’t going to get a shot”. It was a neat job and the pay was great. But it was the knowledge and ‘tricks-of-the-trade’ I picked up from him that has really paid off over the years. I think he took a shower with a camera around his neck..! Needless to say, I always have one ready just in case. I might have missed this tapir if I had left it up in the blind…! Enjoy

BLACK LEOPARD BLUES

My Nikon 400mm ƒ2.8 bread and butter lens fails when a black cat shows-up at a hot spring deep in the ‘Western Forest Complex’ of Thailand.

My ‘black leopard’ 16 years ago posing for the camera…!

For more than 10 years, I have used my trusty Nikon 400mm ƒ2.8 ‘Silent Wave’ lens for 90% of my ‘through the lens’ photographic work capturing many wild animals in Thailand and Africa. It has been a workhorse and the photos it produces are my best. This big telephoto lens is very heavy but is amazingly sharp and handles low-light photography extremely well.

I had no idea it was on the blink until I actually looked through the eyepiece on my camera as a ‘black leopard’ walked into the hot springs one afternoon recently. The lens would not focus and I struggled to get it going. I flipped switches and even changed out my Nikon D3s for my D300s to see if that would work. It was a hopeless feeling not being able to catch this beautiful melanistic cat going about its business in nature.

Walking into the hot springs in the afternoon showing its spots…!

In the meantime, my friend Sarawut Sawkhamkhet in the blind with me was busily clicking away as the black leopard moved about the hot spring taking in minerals. I became frustrated and sat there for a while before I rushed back to my truck (some 500 meters away) where my spare 200-400mm ƒ4 VRII lens was sitting. By the time I got back, the feline had melted back into the forest to further ruin my day.

A female black leopard leaving the hot springs in late 2013…!

Some 16 years ago, I was at this very same location but a little higher up in a tree-blind. This mineral deposit is visited by many predators and prey species alike and is one of the top wildlife photography locations in western Thailand. Large herbivores like gaur, banteng, elephant, sambar, wild pig and barking deer come here, and the big cats including tigers and leopards also come looking for something to eat and drink.

Probably the same leopard as above but camera trapped on a trail next to the blind in early 2013…!

Back then about 4:30pm, a black leopard (probably its grand-father) stepped in as the sun was sinking in the West. This creature moved across the opening in the forest and its spots glowed in the diffused light. It stayed at the springs for an hour before moving down towards me and flopping down on all fours on a fallen log posing for me. That was back in the old slide film days and I was not sure that I had got the shots until they were processed at a lab in Bangkok. The photos from that shoot many years ago are shown here and certainly illustrate how great this location really is.

An important mineral deposit/hot springs visited by many animals situated in the ‘Western Forest Complex’…!

In 2013, I was in the blind again when most likely the same leopard came in. She stayed for sometime and I got some nice shots. I also managed to get a camera trap shot shown here as she walked past the blind.

The moral of this story: Always check your camera and lens before putting it to work, and have a spare close-by in case of failure. If it’s going to happen, it will when you most likely need it as in my case.

Conclusion: Looking back, it was a valuable lesson and hopefully I will learn from it. I have gotten over it now and all I can do is just remember when I captured a beautiful black cat right here when very few images of this species were out there. And finally, there will always be another encounter down the road as these mystical cats live here and I’ll be going back…!

Indochinese tiger sequence

The following images are my best of an Indochinese tiger caught in late afternoon in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, Uthai Thani province, Western Thailand on December 11, 2009. This male moved through the waterhole and did not stay. I had just enough time to get 20 lucky shots of the big cat. A rare sighting of an elusive carnivore..!

Tiger moving into waterhole at 5 pm

Tiger takes a quick drink.

Tiger takes a first look at my location.

Tiger stops and take a second look.

Tiger moves on.

Tiger takes one last look.

The highlight of my wildlife photographic career and a dream come true….!

Photos taken with a Nikon D700 and a 400mm f 2.8 lens on a Gitzo tripod. Exposure: 1/60 sec; f/2.8; ISO 800

Keang Krachan: Rare creatures surviving in the park

A collection of photographs taken from 2001 to 2008

of some rare Asian animals still thriving in this amazing forest

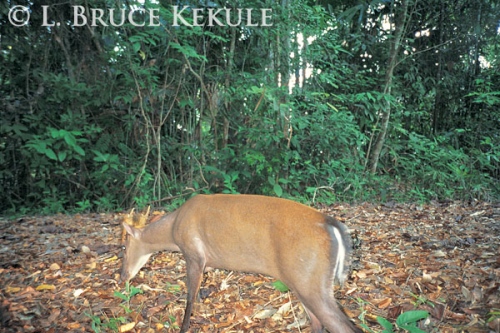

Fea’s muntjac camera-trapped at Kilometer 33 on Phanern Thung mountain

Male muntjac also known as common barking deer at a mineral lick

Male muntjac feeding on leaves

Gaur cow at a mineral lick in the interior

Small gaur herd at another mineral lick

Gaur bull and cow footprint compared to my hand

Asian tapir swimming in the Phetchaburi River

Tapir camera-trapped near the Phetchaburi River

Serow camera-trapped on old logging road

Tusker camera-trapped at a mineral deposit at kilometre 12

Tuskless bull elephant in ‘musth’ camera-trapped on an old logging road

Tiger camera-trapped at a mineral lick in the interior

Indochinese tiger camera-trapped by the Phetchaburi River

Asian leopard camera-trapped on a nature trail

Indian civet caught near Ban Krang campground in the park

Banded linsang camera-trapped on a dry streambed

Banded palm civet camera-trapped by a stream deep in the interior

A king cobra hunting for prey by the Phetchaburi River

A green pit-viper and carpenter ant on a small tree

A green pit-viper swallowing a skink

Reticulated python on the road in Kaeng Krachan

Horny tree frog in a stream deep in the park

Giant tree frog further upstream

Great hornbill flying out of a fruit tree

Oriental Pied hornbill feeding its chicks at the nest

Wreathed hornbill at a nest

Oriental dwarf kingfisher near it nest

Pied kingfishers with a fish on a tree branch

Blue-bearded bee-eater with a beetle for its chicks

Red-bearded bee-eater close to its nest in a sandbank

Black-and-red broadbill with a bamboo leaf

Black-and-red broadbill building a nest

Javan Frogmouth by the Phetchaburi River

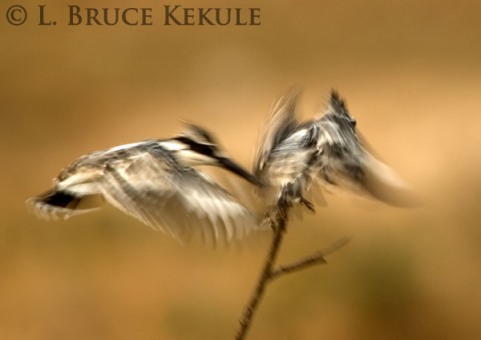

Lesser fish-eagle chick exercising its wings high up a very tall tree

Lesser fish-eagle mother and chick on the nest above the Phetchaburi River

Lessor fish-eagle on a tree branch behind my blind over the Phetchaburi River

River carp in the Phetchaburi River

Gibbon hanging from a bamboo on Phanern Thung mountaintop

Dusky langur near the Phanern Thung ranger station

Stumped-tailed macaque by the river

Rainbow over the Phetchaburi River

Kaeng Krachan National Park is an amazing place but is fraught with poor management and protection. There are many other animals and ecosystems not shown here but this place is truly one of Thailand’s greatest protected areas.

It takes lots of hard work to get down to the river and collect photographs of the creatures thriving there. But diligence, determination, the right equipment, money and with good guides, is also within the reach of serious amateur photographers or naturalists who just want to look.

The opportunities are endless. It is hoped these photographs will create awareness and help this place survive into the future, so that generations to come can also enjoy the beauty of nature in Thailand’s largest national park.

My next post will be a collection of photographs from Huai Kha Khaeng like this of that amazing World Heritage Site, and hopefully sometime before I travel to Africa for a safari to Kenya in mid-August.

Laem Phak Bia Royal Project in Phetchaburi

Bird sanctuary and haven for many species of avian fauna

Laem Phak Bia Environmental Research and Development Project

Pied kingfishers landing in Phetchaburi province

Birds are among nature’s most fascinating creatures. They are the direct descendants of dinosaurs as shown by their detailed anatomy. Archaeopteryx, a 125 myo fossil from a slate quarry in Germany, is the best-known intermediate between toothed dinosaurs and modern birds, but a rich fossil of feathered dinosaurs has since been uncovered by Chinese researchers. The ancestors of modern birds were adaptable enough to survive the great extinction 65 million years ago that wiped out the rest of the dinosaur assemblage.

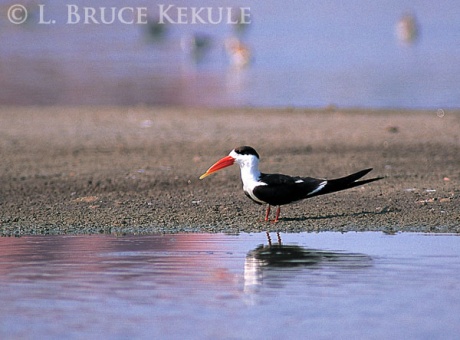

Indian skimmer in salt pans next to Laem Phak Bia

At last count, c. 1000 birds had been recorded in the Kingdom of Thailand. Although some, such as the Giant Ibis and Sarus Crane, have been lost due to hunting and habitat destruction, the continued richness and accessibility of Thailand’s birds and birdwatching sites makes the country a magnet for birders and photographers from around the world.

Indian pond-heron in Laem Phak Bia

One of the best-known birdwatching areas lies in Ban Laem district of Phetchaburi, on the coast of the Gulf of Thailand. It includes the Laem Phak Bia Environmental Research and Development Project, established in 1991, and fully operational by 1995.

Painted stork in Laem Phak Bia

H. M. King Bhumipol Adulyadej initiated the project to treat both wastewater and solid waste through environmentally and ecologically sustainable methods. From a pumping station in Phetchaburi city 18.5 km away, wastewater is fed to Laem Phak Bia through a pipeline. This has created a 1 sq. km freshwater oasis among the surrounding expanse of brackish saltpans. The nutrient input makes this a rich feeding area for water birds and insectivorous land birds, including many that are migrants from northern Asia, together with some other animals such as monitor lizard.

Grey heron in Laem Phak Bia

Laem Pha Bia takes its name from a 3 km ‘sand-spit’ that juts into the gulf. This landform is a meeting point for birds, mammals, reptiles and fish from both sheltered mudflats and mangrove habitat of the Inner Gulf and those inhabiting the exposed sand-beaches of the southern Thai peninsula. The project area includes extensive secondary, regenerating, low stature mangrove forest along its coastal margin.

Little egret and mud-skipper in Phetchaburi

The freshwater lagoons, salt and brackish water expanses, mudflats, sand beaches, marsh grasses, and mangroves, plus the garden and tree plantations around the offices at Laem Phak Bia together constitute an unparalleled diversity of habitats in a small area. In turn, this attracts the highest diversity of birds of any place on the gulf shoreline.

Black-capped night-heron in Laem Phak Bia

From 1999 onwards Philip D. Round, Thailand’s most experienced ornithologist, and others have studied the life-cycles and populations of birds in the project. Such dedication by both professional and amateur birders has made Laem Phak Bia a de facto “bird observatory”, like those in Australia, N Europe and N America. A book, ‘Birds of Laem Phak Bia’, published with support from the Chaipattana Foundation in August 2009, is available from bookshops and at the Royal Project for those interested in learning more about the biodiversity of the site.

Great egret breeding nearby at Ban Laem town

Among the 242 species of bird recorded from the project and surrounding areas one of the most outstanding was an Indian Skimmer that arrived to delight bird watchers and photographers in April 2004. Another scarce visitor was an Indian Pond Heron that showed up on the freshwater ponds in 2006. I was fortunate to photograph both these birds during their short stays.

Brown seagulls in a freshwater pond in Laem Phak Bia

In March 2006 a rare and virtually unknown vagrant bird, the Large-billed Reed Warbler, was also netted and banded inside the project area before being photographed and released. At the time the only previous record in the whole world for this species was from the Sutlej Valley, Northwest India back in 1867. Such an amazing discovery shows both the significance of the project, and the continued conservation importance of the Thai Gulf.

Sunset at Laem Phak Bia

Without doubt, the highly successful Laem Phak Bia Environmental Research and Development Project has not only helped the people of Phetchaburi province by reducing pollution, but also provided nature lovers, bird watchers and photographers a chance to get close to some of Thailand’s remarkable endangered birds and eco-systems. This, of course, is a plus for wildlife conservation, and an example how protection and the safety of wild creatures is enhanced by a Royal Project.

Water monitor or locally known as the ‘Water Dragon’

***************************************************************************************************

Notes on Laem Phak Bia by Phillip D. Round

I was immediately struck by the potential of Laem Phak Bia for studying a huge diversity of both resident and migratory birds when first introduced to the site in March 1999. I also fell in love with the tranquility and remoteness of the nearby coastline. Since that time I have spent as many weekends as I can manage there. In collaboration with the Wildlife Research Division of the Department of National Parks, and with the full support and encouragement of the Environmental Research and Development Project director and staff, I my students, and Bird Conservation Society of Thailand helpers, erect mist-nets in order to catch wild birds. These are then marked with a numbered metal band provided by the department; carefully examined, photographed and released.

Collared kingfisher with a bird band by P.D. Round

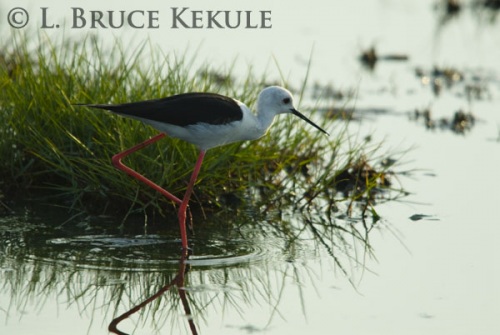

The long-legged and highly migratory shorebirds are additionally marked with coloured leg-flags that enables their country of marking to be recognized by an observer using binoculars or telescope. Birds marked at Laem Phak Bia have been found as far afield as Australia and NE China.

Black-winged stilt in Laem Phak Bia

But even the resident (non-migratory) birds are of enormous interest. Any bird that bears a numbered metal band is effectively carrying an individual identity card throughout its life — essential for detailed ecological study. Who would have guessed that our longest-lived bird was a diminutive (less than 8 g weight) nok krachip (Common Tailorbird) banded as long ago as 2001! Not only have we learnt much about the life-histories, movements and annual cycles of birds, but we have also taught students the safe bird-handling skills they need to run their own research projects elsewhere in Thailand.

Philip Round is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Biology, Mahidol University, and is also the region al representative of The Wetland Trust (UK).

****************************************************************************************************

COMMENT: Over-development in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Since the cover story was about birds, a report on the other famous bird-watching site in Phetchaburi is called for. Kaeng Krachan National Park is one of Thailand’s most important protected areas for wildlife conservation. The dry-evergreen forest is habitat to more than 400-recorded species including the rare Ratchet-tailed treepie found only in northern Vietnam and Kaeng Krachan.

Ten-wheeled dump truck and backhoe at kilometer 18 in Kaeng Krachan

Last year, several expansion projects were introduced into the park including tree clearing, camp area expansion and construction work were undertaken at several locations including the headquarters area, plus Ban Krang and Phanern Thung ranger stations situated in the interior. Bird watchers and photographers from around the world come regularly to see and photograph the birds, animals and these forest ecosystems.

Her Majesty Queen Sirikit visited Phanern Thung and her palace is maintained past the station. Campgrounds and parking areas have now been expanded into every empty space to increase visitors. A roast chicken and ‘som tam’ restaurant is now open every day at the top.

Chicken shop at Phanern Thung ranger station

About 20 years ago when the road into the park was extended past Phanern Thung to a car park at kilometer 36, a new tourist trap was established known as the ‘Sea of Fog’. Then, some professors at Kasetsart University walked down to the Phetchaburi River along a very tough track and set-up camp for extended stay building bamboo furniture and shacks by the waterway known as ‘KU Camp’.

Now, an even more complex VIP bungalow with tables and seats plus two toilets has been erected here, and recently used by some big shots with a campfire, armrests and drink-holders to boot. The trail down to the river is now widened to accommodate rafting crews and one could almost drive down.

Backhoe digging a huge hole to build a water holding tank

And finally the worst: at kilometer 18, a 10-wheeled truck is parked and a big backhoe is digging an enormous hole, supposedly to build a water storage tank. One of the best bird sites in Kaeng Krachan constantly visited by nature lovers is now completely destroyed by heavy equipment working everyday seen in the accompanying photograph.

Also, a natural stream crosses the road past Ban Krang at three locations but are now covered over with pipes and dirt to accommodate cars and two-wheeled traffic. By the look of things, more construction projects will be on the drawing boards to expand visitation even more. It is doubtful if any feasibility studies have been carried out on the impact of all this construction and destruction of natural tranquility.

After visiting and working in Kaeng Krachan for more than a decade, and knowing how important and beautiful this forest truly is, I feel sadden by all this over-development. It is only the beginning but quickly destroying the park to the point of no return, much like Khao Yai National Park in the Northeast. It is hope someone will read this and go see for themselves what has transpired. Action should be taken by the ‘powers to be’ to ensure anymore degradation is stopped before it is too late!

Jewel in The Kingdom – Part Three

Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary

The Ecology

The fauna of Thung Yai includes some 120 mammals, 400 birds, 96 reptiles, 43 amphibians and 113 freshwater fish. Unfortunately, elephant have almost disappeared from the area due to the mining road breaking up migration routes, although passing migrants have been recorded from time to time.

Stream in Thung Yai

There is still a large herd of gaur. However, these ungulates are split up into small groups that prefer to remain in deep cover or ravines during the day. They only come out on to the plains at night. Occasionally, in May and June, after the grassland fires and subsequent first rains, they can be seen during the morning or evening, feeding on the newly sprouted young grass.

Samurai spider

Sambar, common muntjac (barking deer), wild pig and serow are common here. An area in the western part of the sanctuary supports tapir. Fea’s muntjac, a rare deer species similar to barking deer is also found here. With sizeable herds of large prey animals, tiger, leopard and Asian wild dog will survive. Smaller mammals like the leopard cat, civet cat and porcupine are very common and easily seen along the road at night. The bamboo rat is often heard gnawing away underground in bamboo clumps but is seldom seen. Unfortunately, these large rodents are poached by the ethnic tribes people for their meat and are thought to be dwindling in numbers.

There are a quite a few mineral licks in Thung Yai visited by gaur, sambar and barking deer plus many species of birds including the mountain imperial pigeon, pin-tailed pigeon and blue magpie, all of which come to take in minerals. The magpie is often seen perched on the herbivores eating bothersome ticks.

Oakleaf butterfly

Many other bird species live here, including the very rare white-winged duck spotted at a few remote forest lakes. The crested kingfisher and the Oriental darter, also rare, have been seen along a few waterways.

One of the oldest plant species in Thailand, the cycad, can be found in Thung Yai. These beautiful plants were around during the time of the dinosaur and may be seen from the road. Many types of orchid flower here during February and March. One of the most notable is the elephant orchid, which can be found in the interior. Beautiful wild ginger is also found in the grasslands.

The flora and fauna of the sanctuary intermingled includes Sundaic, Indo-Burmese, Indo-Chinese and Sino-Himalayan species, with many not found elsewhere. It is a researcher’s heaven, and some of the Kingdom’s last untamed riverine habitats.

Tokay lizard at Song Tai ranger station

The topography is generally mountainous with a network of many permanent rivers and streams dividing the area into valleys. The principal vegetation types are hill evergreen, dry evergreen, mixed deciduous, dry dipterocarp, savannah forest and grasslands. Red-brown earths and red-yellow podzolic are the predominant soils. A physical feature that is important for wildlife is the presence of mineral deposits or licks. These occur throughout the sanctuary, either wet or dry, and most appear to be located on or around granite intrusions in areas with red-yellow podzolic soil. They may be associated with the massive faults or lines in the intensely folded geology of this area. Small lakes, ponds and swampy areas occur, some seasonable while others are perennial; these are important wildlife habitats. Limestone sinkholes are found; most are about 20 meters across, but some are two kilometers long, 250 meters wide and drop as much as 30 meters in depth.

Wild ginger in the savanna

Caves, just south of Thung Yai, are well-known sites of early hominid occupation, dating back thousands of years. Paleolithic, Mesolithic and neolithic stone tools have been found in the Khwae Noi and Khwae Yai valleys. Burial sites from a much later period have also been found here, and in Huai Kha Khaeng to the east. The only Thai presence known in history was sometime between 1590 and 1605 when King Naresuan based his army in Thung Yai to wage war against the Burmese invaders.

Jewel in The Kingdom – Part Two

Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary:

Thailand’s largest protected area and World Heritage Site

A look at present-day Thung Yai

When construction of hydroelectric dams was in vogue back in the early 1980s, the Mae Nam Choan dam project was put on the drawing board. If completed, it would have devastated about a thousand square kilometers of absolutely pristine habitat in Thung Yai including parts of the grassland. Many beautiful creatures would have perished or been pushed into the steep terrain by the rising floodwaters.

Mae Nam Choan

Logistics was a nightmare due to the rough terrain where the dam site was planned but the designers persisted. The Electrical Generating Authority Thailand (EGAT) cut a road through virgin forest in the sanctuary to the Mae Nam Choan River and a large supply camp was built.

Female muntjac in Song Tai ranger station

Conservationists organized a protest against construction of the dam. Grassroots people, NGOs, movie stars, pop stars and religious groups all joined the fracas and stayed until 1988, when the project was officially scrapped. This long-lasting protest was the first big success for wildlife conservationists in Thailand, and an instance in which the government was forced to yield to public opinion. The river still runs wild today. A legacy of preserving the natural world was set in place. Further outcries against mega-schemes in other parts of the country were brought to the forefront.

Large Indian civet at night in Song Tai

Nonetheless, the threat of large-scale destruction of natural habitat through the building of dams remains today, both within Thailand, and on key rivers in adjacent countries. Power producers, irrigation officials and others with political influence, want to build dams, sometimes just for the money. But with other alternate sources of power, building a dam purely to generate electricity is not credible.

China, Burma, Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia all have dam projects on the drawing board, recently completed or are under construction. The future of many rivers and wilderness areas in Southeast Asia is grim as modernization continues to wreck havoc on the natural world.

Forest monitor on a tree close to the Choan River

In 1996, I began visiting this wonderful place photographing its wildlife and forest. On my first trip into the interior, I miscalculated the distance to the headquarters at Song Tai and almost run out of fuel for my old ‘Series 1 Land Rover’. The chief at the time, Manop Chumpoochun gladly helped with enough gas to get back out to the nearest pump. Manop (now retired from the government) and I have been friend’s ever-since and we get together from time to time. He was a big help in finding wildlife subjects to photograph.

In those days, the road was tough especially after a rain but was still negotiable in most places. However, off-road groups from Bangkok would sometimes enter in large groups of 25 or more vehicles tearing up the road in certain areas making deep ruts where water naturally seeps from the ground creating havoc. Detour roads were then cut where possible further destroying the forest and making the road extremely rough on standard 4X4 trucks used by the rangers.

Siamese cat snake after eating a bird from a nest

Years later, the department set-up a new rule allowing only three off-road trucks at a time, which was suppose to cut down on the amount of vehicles that entered. However, the trick then used by these off-road groups was to mass outside the sanctuary and enter in groups of three gathering in the forest later where big parties were held. Racing at breakneck speed and testing their automobiles, tires and suspension systems was the program without any thought for the rangers or the forest and wildlife.

Due to political pressure and leverage, it seems some of these off-road groups continue to enter Thung Yai when permission is granted. Evidence of their passage is found every few kilometres or so. It is without doubt – Thung Yai is the toughest challenge for these thrill seekers in Thailand. It certainly needs attention and a proper mandate set-up by the DNP. These off-road groups should be scrutinized before allowing entry to minimize further destruction.

Asian barred owlet in the morning at Song Tai

Due to the state of the road, patrolling has always been kept to a minimum. It is also very difficult with just a few vehicles, a small staff, and a restricted budget that continues to cripple the protected area. Both Thung Yai west and east have similar problems relating to encroachment and poaching.

Another damaging aspect is the amount of regular traffic on the road through the middle of the sanctuary to the Karen village of Jagae. There is almost daily travel to and from the village, either people walking through or as motorized transport, especially during the dry season. Also, Buddhist monks enter for spiritual reasons or are in transit, possibly in the hundreds during the dry season. A taxi service of off-road vehicles runs from the mining town of Klity to Jagae and back, and the flow of people are basically unrestricted.

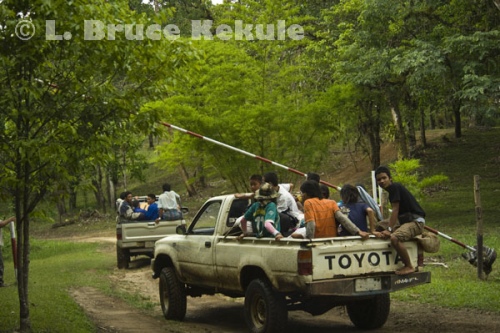

Taxi service in Thung Yai – Excessive traffic through the sanctuary

and a drain on the environment

Recent settlements are either Hmong or Karen, and there are about 15 villages situated within the boundaries of the protected area. The villagers claim they have been here for more than 150 years. The big question is: where will these people expand? They seem most likely to take over more fertile areas, displacing the wildlife, and turning it into agricultural farmland, or for grazing livestock.

In 1996 the village of Jagae had about a 100 households compared to just a dozen when the sanctuary was gazetted in 1974. Now there are more than 300 homes plus a school with possibly a thousand children. A large contingent of Border Patrol Police exists here too. It would be near impossible to move the mine and or the village, which has become completely entrenched.

My Ford Ranger entering a deep hole

To protect the grassland interior, a substitute route should be built from Jagae, going west into the town of Sangklaburi. Several bridges would need to be constructed to make the road suitable for all-weather use. So far, that remains just an idea. Hopefully some day, the government will address this problem and do something about these concerns to help preserve Thung Yai for the future.

As it stands, more and more people will continue to use the road, year in, year out, polluting it with trash. Poaching and forest gathering still remains a serious problem. Several years ago, a research team found two headless gaur carcasses side by side at an important mineral lick, indicating the beasts were killed with a large caliber rifle. Only the trophy and some meat were taken. All the protected areas in the ‘Western Forest Complex’ is plagued by the same problems related to gathering, poaching and encroachment.

Thung Yai’s tough road and my poor truck

It is vitally important to preserve Thung Yai Naresuan and Huai Kha Khaeng plus Umphang wildlife sanctuaries as one continuous conservation area – to maintain the integrity of habitats, the diversity of the flora and fauna, and complexity of all their ecosystems. Not enough is being done to restrain the relentless tide of humanity. Quick and decisive action is the only recourse, before it is too late.

Jewel in The Kingdom – Part One

Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary:

Thailand’s largest protected area and World Heritage Site: A look at present-day Thung Yai

Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary established in 1974 is the single largest protected area in Thailand encompassing 3,647 square kilometers. Named after King Naresuan the Great who repelled Burmese invaders back in the 16th century gaining independence for the Thai nation. The sanctuary is not only historically famous but one of the Kingdom’s greatest natural wonders.

Sunset over the grassland in Thung Yai

Due to its size, the sanctuary is divided into two separate administrative blocks – east and west for easier management, and each with its own superintendant. The most important part of this great place is the grassland or savannah in the middle of the western section. The sanctuary gained this status due to the biodiversity of its flora and fauna, and the absolute need to save this vast area from further human destruction.

Cycad on the savannah

Thung Yai is a UNESCO World Heritage Site (established in 1991) along with Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary to the east. Adjoining Thung Yai in the south is the Sri Nakharin, Khao Laem and Lam Klong Ngu national parks, and Umphang Wildlife Sanctuary to the north. This cluster is part of the Western Forest Complex that comprises of 18 protected areas under the responsibility of the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP).

Bamboo by the road in Thung Yai

After many months of planning, a trip with my team to Thung Yai (west) situated in Kanchanaburi province on Thailand’s western border with Myanmar was undertaken. We entered the sanctuary on May 1st at Ti Nuay, the present day headquarters area. I was interested to see how this important wildlife sanctuary was coping in the present day, and to observe the impact of humans on its fragile ecosystems. Unfortunately the protected area has a history of ill-fated exploits.

On May 1, 1973 a military helicopter coming from Thung Yai crashed in Nakhon Pathom rice fields northwest of Bangkok. The son of the pilot was killed on impact. Trophy heads, antlers and elephant ivory including weapons were splayed all over the crash site. It made big news and led to the fall of Field Marshal’s Thanom Kittikachorn and Praphas Charusathien’s regime.

The implications of this scandal were serious. In the group were high-ranking government officials, army and police plus movie stars and big business men. Personnel and equipment were provided by the army including a helicopter, GMC trucks, jeeps and local guides hired out by the organizers. It was suppose to be a ‘safari’ for the rich on Thailand’s largest savannah after large wild trophy animals.

Gaur bull camera trapped in a mineral lick

One story floated out that gaur and elephants had been slaughtered in the grassland using the door guns on the Huey helicopter. Other stories like nightly spotlighting and large mammals left to rot in the forest while wild deer meat was served during parties that went on into the night. All the officials on board the disastrous crash were transferred to in-active posts. It certainly made a dent on wildlife conservation and the long-term plight of the sanctuary. However, this prompted the Royal Forest Department (RFD) to gazette Thung Yai as a protected area the following year.

Prior to the crash, mining companies in Bangkok gained mineral concessions in several areas around Thung Yai to mine lead-zinc and other associated minerals like silver, palladium and antimony to name a few. The concessionaires cut a road right through the heart of Thung Yai from the town of Klity northeast of Thong Pha Phum. The dirt and rocky road snakes all the way to the Burmese border and then carries on into Burma for about 10 kilometres before looping back into Thailand. The thoroughfare then continues on to the town of Sangklaburi (Three Pagoda Pass) and is used by local villagers. In the past, big 10-wheel mining trucks with straight exhaust pipes screamed through Thung Yai during the dry season causing extreme noise pollution and disturbing the wildlife.

Gaur cow camera trapped at a mineral lick

A group of mines situated along the sanctuary’s border include Phu Jue, Phu Mong and Kao Lee mines. On the southern side are the Klity, Bo Ngam, and KEMCO (or Song Thor) mines plus a number of other small-scale operations, all with lead separation plants.

These lead mines are killing ethnic communities and contaminating water sources here. Several Karen villagers particularly at Lower Klity village have already died from lead contamination while many dozens of people particularly women and children are suffering from acute lead poisoning by drinking, fishing and washing in the Klity stream near the village.

More than 100 cattle have died and the villagers cannot drink from the waterway because it makes them ill. Some forest rangers in Thung Yai believe that wildlife is also suffering as they have seen deer and other animals dying in the same way as the cattle.

Red-whiskered bulbul

The Pollution Control Department investigated the area and found the amount of lead in sediment in Klity stream below the mine is 165,720 to 552,380 ppm (parts per million). Thailand’s safety standard is 200 ppm. A subsequent investigation by the department revealed the mine failed to treat its wastewater and illegally dumped it into the stream.

The mines have been operating for more than 40 years by influential people with connections to local officials and a political party. Although the lead mines are located just outside Thung Yai Naresuan Sanctuary, the effects of contamination from toxic discharge is spreading far beyond the mine concession areas.

In July 2006, the Natural Resource and Environment Minister Youngyuth Tiyapairat said the RFD reported that the permit for the mining firm to use the land in the forest was about expire (2007) while the Director General Damrong Pidej of the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department would not allow the company to go into the forest either. Damrong also said operations at the mine, which is located in a 70,000-rai forest just past the Karen village of Jagae, has been stopped for almost a decade but the mining company now wants to re-open it and is fighting with the court to resume operations.

Mr Damrong said he would use environment-related laws to bar mining of all kinds of minerals in the wildlife sanctuary especially since it is a World Heritage Site. He called on other agencies concerned, including the RFD and the Department of Minerals to stop granting mining concessions in forested areas.

Mr Yongyuth also ordered forest officials to tightly guard the area to prevent the transport of mining equipment in or out of Thung Yai. He also pushed legislation through parliament to help the rangers improve their standard and grade, and today, more than 50 percent of the DNP’s staff is now permanent hire, a big improvement over the old days when 90 percent were temporary hire.

Mae Nam Choan river

The sanctuary has many rivers and streams. These include the Mae Khlong (Upper Khwae Yai), Suriya, Dongwee, Songthai, Tsesawoh and Maekasa, plus other smaller tributaries. The Mae Khlong River begins its long journey in Umphang Wildlife Sanctuary in the western part of Tak province near the border with Burma. The Mae Chan River, another major tributary, merges with the Mae Khlong in Thung Yai. From there, this waterway, known as Mae Nam Choan or the Upper Khwae Yai River, is steep, swift and rocky. It eventually flows into the Sri Nakharin reservoir which inundated 418 square kilometers to the south of the Thung Yai. The Sri Nakharin Dam in Kanchanaburi was built to harness this powerful river and provide power and water to people on the lowlands.

Wild Water Buffalo – Part Two

WILD SPECIES REPORT: The last wild herd in Thailand

Massive beasts with a mean temperament

Wild water buffalo calf by the river

Probably, the most significant species in Huai Kha Khaeng is the wild water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis). Due to a very small population with only about 50-60 individuals surviving, the future of these remarkable creatures in Thailand is uncertain. Many perils threaten them, such as foot and mouth disease, which could easily be passed on by domesticated buffalo living just outside the southern boundary of the sanctuary. Poaching and encroachment are also serious concerns.

Mother buffalo fully alert to any danger

I once photographed a female (with a rope through her nose) and a few of her calves mingling with a wild herd in the sanctuary not far from the southern boundary. I made a report to the authorities, and these domestic buffalo were separated from the wild herd and quickly chased out by the rangers.

Domestic buffalo mingling with the wild herd

It is a fact though; some local villagers have deliberately mingled their buffalo with the wild buffalo so the offspring would be sturdy. This is a very dangerous situation, which if not checked, may lead to the total demise of all the ungulates like deer, pigs and wild cattle in Huai Kha Khaeng. It may sound drastic, but that could happen one day. Cattle disease has no boundaries.

The southern border at Krueng Krai ranger station still remains a gateway for danger and must be protected at all costs. However, enforcement is difficult due to low budgets and just a few rangers to look after a very large area. This needs a serious revamp. The Department of National Parks (DNP) has increased security here but some locals seem intent on slipping through.

Wild water buffalo herd

Stricter laws are needed as a deterrent, and increased budgets and personnel implemented so this wonderful place is properly looked after. Anyone caught in the interior with firearms and evidence of poaching should do a long prison term. Unfortunately, with the present laws and possibility of corruption, law-breakers usually get off light and become repeat offenders.

Over the years, I have seen these magnificent buffalo on numerous occasions. During the late 1990s’ while I was still shooting film and working in Huai Kha Khaeng at the southern area, I managed to get some good shots of a herd wallowing in the river. But it was not the first or the last time I would bump into wild water buffalo.

Wild water buffalo herd

In 2006 armed with a new Konica-Minolta D7 digital camera and 600mm lens, I bumped into two bulls right across from Krueng Krai ranger station. One was a very old bull with a huge set of horns, and the other a younger bull posed for the camera over the course of several days. I was using a boat-blind but had no power except a paddle, and getting around was a bit difficult. However, it was still very gratifying seeing these rare beasts and photographing them.

Late last year, I had a unique experience photographing a young male calf and its mother. Green peafowl and otters are plentiful but my main objective is always the same, photographing the buffalo. My last encounter was in March of this year. I again motored up-stream and bumped into two large bulls cooling off in the river. They were very shy and took off as soon as they saw me but not before I got a couple of good shots. Judging from their horns, these two were very mature bulls.

Very old wild water buffalo bull

At the beginning of the dry season, the river is very low but still deep enough to navigate up-stream using a new camouflaged kayak with pontoons on either side, and a silent trolling motor hooked up to a 12v truck battery for power and maximum maneuverability. Controlling the boat-blind is easy as I motor along using the electric motor and I can easily steer the craft with a rudder made of aluminum attached to the stern. I use three anchors (one fore and two aft) when I need to be steady in the water.

A Nikon 400mm f 2.8 lens and camera is firmly attached to the hull using aluminum tubing and braces plus a gimbal-styled tripod head suitable for a large telephoto. I sit comfortably behind the camera ready to shoot at a moments notice. This boat actually is very stable and has allowed some close encounters with large mammals. Camouflage material is draped over everything to blend in with the background.

Wild water buffalo herd

Over the years, quite a lot of research has been carried out on the buffalo in Huai Kha Khaeng. One of the first was Napparat Naksathit, the former chief of Khao Nang Ram Research station. He did an ecology and distribution survey of buffalo in 1984. Then Tanya Chan-art in 1986 and Wichan Ucharoensak in 1992, did consensus surveys to determine numbers. Dr Rattanawat Chaiyarat from Mahidol University did his thesis on the buffalo. Dr Terrapat Prayurasiddh, now the deputy director general of the Royal Forest Department, did an aerial survey using a helicopter, also to establish numbers. Around that time, the deputy chief of Huai Kha Khaeng, the late Pongsakorn Pattapong researched and photographed the buffalo. He was an avid photographer but passed away from too much exposure to chemicals while developing his own film. And finally, Manoch Yindee is currently working on wild buffalo genetics in the sanctuary, and domestic buffalo throughout the Kingdom.

A mature buffalo bull can weigh up to a ton with hooves more than 20cm (8 inches) across. They leave deep tracks in the sandy soil by the river. These magnificent bovids are much larger and more aggressive than their domestic counterparts. Wild buffalo have a distinct forehead with horn bases closer together than domestic buffalo, whose boss is wider apart.

Wild buffalo have a fierce temperament and if provoked, can be very dangerous to man. A herd will group together to face a predator like a tiger or Asian wild dog. Male solitary bulls charge without hesitation. Many a hunter has had a close call or been killed by these massive low-slung beasts. A bull will gore and then toss the intruder before stomping on the victim with its huge hooves. They are extremely determined and will sometimes continue to attack until the enemy perishes.

The author in an old boat-blind

Buffalo live in herds with one mature bull looking after the females. During the breeding season in October-November, the herd bull will fight other solitary bulls. Females have one calf, and gestation is about 10 months. A buffalo’s daily ritual is a visit to the river to drink and cool off. They will wallow to coat their hides with mud protecting it from biting insects.

This is the last wild herd in Thailand and, in Southeast Asia for that matter. India and Nepal have some large herds, and Cambodia may have a few individuals but they could be feral. Centuries ago, wild water buffalo were found in alluvial lowland plains and rivers throughout the Kingdom. As most waterways have been overcome by humanity, domestication of the wild buffalo was only a matter of time. It is said wild buffalo were domesticated before 2000 BC. Fossil evidence of buffalo from the Pleistocene Epoch has been uncovered in many sand deposits along the Chao Phraya River.

Antlers of a Schomburgk’s stag

The DNP is responsible for Huai Kha Khaeng and its management, and they should make protection and enforcement around the southern area a top priority. With only one location for wild water buffalo left in the Kingdom, total security is required so these magnificent creatures will be around for future generations to appreciate. It is hoped they will not end up like so many other animals that have gone extinct such as the Schomburgk’s deer and the Kouprey, and that would be a sad day indeed.

Trophy horns of a Kouprey bull