Archive for the ‘The South’ Category

The Gurney’s Pitta: Thailand’s flagship species

THE GURNEY’S PITTA – A bird no more…!

Now officially extinct in Thailand

A male Gurney’s Pitta photographed by me way back in early 2001 in Southern Thailand…!

In October 2001, I did a story entitled ‘On the verge of extinction’ for the Bangkok Post’s ‘Nature Section’ about an amazing bird that had been rediscovered in 1986 by my close friend and associate Phillip D. Round, Thailand’s eminent ornithologist after almost three decades of no sightings. Prior to that, it was thought to be extinct in the Kingdom. The bird was listed as a flagship species for conservation and put on Thailand’s 15 reserved species list.

The Gurney’s pitta (Pitta gurneyi) is a medium-sized passerine bird that completely disappeared from all lowland evergreen forest south of Prachuap Khirikhan province where natural forest was destroyed primarily to grow palm oil and rubber trees except for one little patch in Krabi province. This site is known as Khao Nor Chuchi or Khao Pra-Bang Khram Wildlife Sanctuary – the only known place in Thailand where this rare pitta still survived. The area definitely needed extreme management to save this creature from extinction.

In historic times, the range of the Gurney’s pitta was along the coast and inland areas on both sides of the Thai peninsula, in the provinces of Trang and Krabi on the western side, and Nakhon Si Thammarat, Surat Thani, Chumphon up to Prachuap Khirikhan on the east. It also survived in southern Burma where this beautiful bird was first discovered way back in 1875 by a wildlife specimen collector working for Allan Octavian Hume, a prominent ornithologist. The exotic bird was named rather prosaically after Hume’s friend, J.H. Gurney, a Fellow of the Zoological Society of London.

Lowland rainforests up to 200 meters above sea level are home to an unsurpassed diversity of flora and fauna including the Gurney’s. Due to excessive human settlement and agriculture, this unique bird has diminished to the point of no return here in Thailand.

A male Gurney’s Pitta in photographed in Khao Phra-Bang Kram Wildlife Sanctuuary – 2011…!

However, over in Burma, there are purported to survive after quite a few surveys since early 2003 when Jonathan Eames with BirdLife International and other associates found the bird at four different sites. Jonathan returned in 2004 and found more locations with the bird but political instability and very restrictive government regulations threaten to keep researchers away, while landmines and bandits further discourage access.

My first encounter with a Gurney’s was back in 2001 when I made an effort to capture this bird on film. I managed to get one shot…the following is that account. “Dark morning stillness in thick lowland rainforest is broken by muffled footsteps as two humans move slowly down the trail. We carry heavy camera equipment to a photographic blind erected deep in the jungle the previous evening. Condensation is heavy as I set up in the hide. My friend and guide, Douglas Judell departs quickly and noisily – the intent being to convey the message that both of us have left the area.

As animals of the night retreat, I wait for the first signs of dawn. My goal is to photograph this elusive pitta known to frequent this small patch of forest. Morning light awakens the jungle and the sounds of dripping moisture begin to be replaced by the noise of birds and insects starting their day. Hidden in the blind, I remain vigilant for the slightest movement on the forest floor. About 8am, light from the sun filters through the canopy in patches.

The Emerald Pool in Khao Phra-Bang Khram Wildlife Sanctuary, home to the Gurney’s Pitta in Krabi province…!

A sudden movement shows a hooded pitta, another species common here, hopping about looking for earthworms. This striking blue, green and red bird with a dark brown crown moves closer to the blind seemingly oblivious to the looming structure. Snapping only a few shots for fear of alarming the other denizens of this forest, I continue to sit quietly hoping the ‘forest spirits’ will answer my wish.

A passing morning rain shower is short and as if on cue, a blue, black, yellow and white bird suddenly appears in front of the blind about five meters away as the rain stops. Perhaps sensing danger, it quickly hops into the darkness of the forest but a minute later returns just long enough for only one shot of this rare bird. I quickly forgot about the wet grubby conditions and the long road trip of more than 700 kilometers from Bangkok to this place. I was elated to say the least.”

When I did the story in 2001, there were about 11 pairs and some individuals left in the sanctuary. The decline was evident and it became a worry for the Department of National Parks (DNP). Drastic measures were needed but they never came. When Khao Pra-Bang Khram was up-graded in 1987 by the Royal Forest Department (RFD) from a non-hunting area to a wildlife sanctuary, most of the forest where the bird was actually found unfortunately was not included in the protected area. It is a wonder how things sometimes come to pass.

This then became a pitched battle between conservationists, local villagers and the DNP. Forests were being cleared for palm and rubber and there was nothing the department or NGOs’ could do in certain areas because this land was outside the sanctuary and was the property of the locals. Forest destruction was severe and it put a terrible strain on the ecosystem.

Another very negative aspect is the visitation by hundreds of tourists almost daily at the Emerald Pond not far from the core area. This place use to be peaceful and beautiful, and a decade ago there were just a few noodle stands and trinket shops at the front. Now this has expanded 100 percent and has become a big business catering to the visitors. Buses and vans are parked everywhere. There are very few birds around the pond now and trash is a serious problem.

The Gurney’s pitta is now officially extinct in southern Thailand’s lowland rain forests..! In 2004, I published ‘Thailand’s Natural Heritage’ and I predicted then that the species would eventually disappear. Now that this beautiful creature is gone from the natural world, it is a sad day for nature conservation in the Kingdom of Thailand.

Gurney’s Pitta – The last few stragglers

WILD SPECIES REPORT

Avian fauna on the brink of extinction in Thailand

Gurney’s pitta male – one of the last few surviving birds at Khao Nor Chuchi

In October 2001, I did a story entitled ‘On the verge of extinction’ for the Bangkok Post Nature section about an amazing bird that had been rediscovered in 1986 by my close friend and associate Phillip D. Round, Thailand’s eminent ornithologist after almost three decades of no sightings. Prior to that, it was thought to be extinct in the Kingdom. The bird was listed as a flagship species for conservation and put on Thailand’s 15 reserved species list.

The Gurney’s pitta Pitta gurneyi is a medium-sized passerine bird that completely disappeared from all lowland evergreen forest south of Prachuap Khirikhan province where natural forest was destroyed primarily to grow palm and rubber trees except for one little patch in Krabi province. This site is known as Khao Nor Chuchi or Khao Pra-Bang Khram Wildlife Sanctuary – the only known place in Thailand where this rare pitta still survived. The area definitely needed extreme management to save this creature from extinction.

A Gurney’s pitta female in Khao Nor Chuchi

In historic times, the range of the Gurney’s pitta was along the coast and inland areas on both sides of the Thai peninsula, in the provinces of Trang and Krabi on the western side, and Nakhon Si Thammarat, Surat Thani, Chumphon up to Prachuap Khirikhan on the east.

It also survived in southern Burma where this beautiful bird was first discovered way back in 1875 by a wildlife specimen collector working for Allan Octavian Hume, a prominent ornithologist. The exotic bird was named rather prosaically after Hume’s friend, J.H. Gurney, a Fellow of the Zoological Society of London.

Lowland rainforests up to 200 meters above sea level are home to an unsurpassed diversity of flora and fauna including the Gurney’s. Due to excessive human settlement and agriculture, this unique bird has diminished to the point of no return here in Thailand.

A male Gurney’s pitta photographed is 2001

Encroachment and forest destruction has not been the lone evil. Some poaching of the Gurney’s for the black market trade have also taken its toll. It is said a pair of a male and female fetches a hundred thousand baht or more from rich collectors of exotic birds at the infamous Chatuchak Market in Bangkok. In fact, the bird’s beauty has been its worst enemy. Even though protection and enforcement has improved over the years, catching the big traders and buyers of wildlife black market items has been slow and sometimes non-existent at times.

However, over in Burma, thousands of Gurney’s are purported to survive after quite a few surveys since early 2003 when Jonathan Eames with BirdLife International and other associates found the bird at four different sites. Jonathan returned in 2004 and found more locations with the bird but political instability and very restrictive government regulations threaten to keep researchers away, while landmines and bandits further discourage access.

Since then, Dr Paul Donald of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) has surveyed many areas and confirmed that almost all of the world’s population of Gurney’s pitta is located in Myanmar but the forests there are also being decimated for palm and rubber agriculture and hence, the bird there is still under serious threat. This granted the species a reassessment from the IUCN, going from critically endangered to endangered.

Hooded pitta with worms feeding its chicks somewhere in the forest

My first encounter with a Gurney’s was back in 2001 when I made an effort to capture this bird on film. The following is an account of that wonderful moment that was very brief, and I only managed to get one shot shown in the story.

“Dark morning stillness in thick lowland rainforest is broken by muffled footsteps as two humans move slowly down the trail. We carry heavy camera equipment to a photographic blind erected deep in the jungle the previous evening. Condensation is heavy as I set up in the hide. My friend and guide, Douglas Judell departs quickly and noisily – the intent being to convey the message that both of us have left the area.

As animals of the night retreat, I wait for the first signs of dawn. My goal is to photograph this elusive pitta known to frequent this small patch of forest. Morning light awakens the jungle and the sounds of dripping moisture begin to be replaced by the noise of birds and insects starting their day. Hidden in the blind, I remain vigilant for the slightest movement on the forest floor. About 8am, light from the sun filters through the canopy in patches.

One of several hooded pittas that showed-up looking for earthworms

A sudden movement shows a hooded pitta, another species common here, hopping about looking for earthworms. This striking blue, green and red bird with a dark brown crown moves closer to the blind seemingly oblivious to the looming structure. Snapping only a few shots for fear of alarming the other denizens of this forest, I continue to sit quietly hoping the ‘forest spirits’ will answer my wish.

A passing morning rain shower quickly passes by and as if on cue, a blue, black and yellow bird suddenly appears in front of the blind about five meters away. Perhaps sensing danger, it quickly hops into the darkness of the forest but a minute later returns just long enough for only one shot of this rare bird. I quickly forgot about the wet grubby conditions and the long road trip of more than 700 kilometers from Bangkok to this place. I was elated to say the least.”

My first Gurney’s pitta male photographed by ‘U’ trail

When I did the story in 2001, there were about 11 pairs and some individuals left in the sanctuary. The decline was evident and it became a worry for the Department of National Parks (DNP). Drastic measures were needed but they never came. When Khao Pra-Bang Khram was up-graded in 1987 by the Royal Forest Department (RFD) from a non-hunting area to a wildlife sanctuary, most of the forest where the bird was actually found unfortunately was not included in the protected area. It is a wonder how things sometimes come to pass.

This then became a pitched battle between conservationists, local villagers and the DNP. Forests were being cleared for palm and rubber and there was nothing the department or NGOs’ could do in certain areas because this land was outside the sanctuary and was the property of the locals. Forest destruction was severe and it put a terrible strain on the ecosystem.

Emerald pond algae not far from the sanctuary headquarters

Another very negative aspect is the visitation by hundreds of tourists almost daily at the Emerald Pond not far from the core area. This place use to be peaceful and beautiful, and a decade ago there were just a few noodle stands and trinket shops at the front. Now this has expanded 100 percent and has become a big business catering to the visitors. Buses and vans are parked everywhere. There are very few birds around the pond now and trash is a serious problem.

Two weeks ago, I made one last ditch effort to photograph this bird. Permission to enter the sanctuary was graciously given by the Wildlife Conservation Division at DNP in Bangkok. I packed-up my old pickup truck and headed South to the small village in Krabi province named Ban Bang Tieo where the sanctuary headquarters is situated.

I met with the new superintendent Nikom Srilamoon of Khao Pra-Bang Khram, requesting authorization to enter the sensitive area in order to catch the Gurney’s on digital. He has certainly inherited a tough job!

Emerald Pond in Khao Pra-Bang Khram

The first day was comprised of walking the nature trails ‘U’ and ‘N’ where the bird is normally found to see first hand the situation on the ground. Many parts are, overcome by humans and their destructive vises of throwing trash on the ground and cutting trees down. Someone has established a rubber plantation in the remaining core area of the sanctuary. Motorcycle tracks are everywhere and it is said spot-lighting for night creatures like frogs and mouse deer goes on. It seems that just about every square meter is under threat.

The next morning, I decided to set-up a quick blind in a palm plantation that borders forest early the next morning at first light. About 7am, a couple female pitta skirted the forest for a couple of meters and then melted back into the thick vegetation. I did not get a shot, as they were too quick.

Palm oil plantation butted-up to the forest in Khao Pra-Bang Khram

In the afternoon, I went back into the trail system to scout a new location. I chose to erect a blind in a gulley with a stream that cuts through the habitat. Sharp thorns are everywhere but it is very secluded from the main nature trails and excessive activity.

The following morning I was sitting alone in the dripping forest at 5.30am sharp. My two helpers departed quickly after installing a slave flash on a tree to the left of my position. Then the rain started and did not let up until late afternoon when the sun finally peaked through the clouds for a short period.

Another male photographed in the sanctuary

Birds immediately began calling and activity picked up. Then, I saw movement ahead and a male Gurney’s popped out of the forest and stayed in front of the blind for only a few seconds as I fired off a short burst including the lead photo. It was exciting, and will be etched in memory. These creatures are still surviving here but they are now hard to locate and stay elusive for the most part. I thanked the ‘spirits of the forest’ for this rare encounter, and the rain came again till just before darkness.

BirdLife International, BirdLife Denmark, DANCED, Bird Conservation Society of Thailand, the Oriental Bird Club and the RSPB have helped the DNP to implement numerous projects at Khao Nor Chuchi, but these efforts have only slowed rather than halted new settlements and the destruction of the forest.

Banded pitta male at Khao Nor Chuchi

The population of Gurney’s pitta at Khao Nor Chuchi has declined drastically, dropping from an estimated 40 pairs in 1986 down to about 20 pairs in the mid-1990s’. At one abandoned nest, local researchers found bird (mist) nets placed by some people to capture this rare bird. The last estimate from various sources on the number of birds is less than ten individuals (both male and female) survive in the core area. This is serious and the prospect of extinction is truly depressing.

Banded pitta female at Khao Nor Chuchi

Unless Khao Pra-Bang Khram protection and enforcement can be quickly implemented and expanded to include all the remaining intact lowland forest, and previously cleared areas are reforested, the species in Thailand faces a very bleak future. Quick and decisive action is the only remedy and it is absolutely no use pointing the finger of blame on anyone.

As a flagship species for the conservation of southern Thailand’s lowland rainforest, only time will tell if the Gurney’s pitta can survive. If this beautiful creature disappears, it will be a sad day for nature conservation in the Kingdom.

THAILAND’S 15 RESERVED SPECIES

Thailand’s list of 15 reserved species is so out-dated it is now covered in dust and needs updating. Two lists should be established: one for species that are truly extinct in the wild, and another list for rare creatures like tiger, leopard, gaur, banteng, Asian elephant, Asiatic bear and sun bear plus the remaining survivors shown below. There are also many other wild animals that need special status!

1) White-eyed river martin: Presumed extinct globally since 1985-86. The last known specimens were from Bueng Boraphet Non-hunting Area in Nakhon Sawan province.

2) Javan rhino: Once found in many large forests and now extinct in Thailand for more than 25 years.

3) Sumatran rhino: Extinct in Thailand for more than a decade or two. A few individuals were reported in Hala-Bala Wildlife Sanctuary. down south in Narathiwat province.

4) Kouprey or grey ox: Extinct in northeasternThailand for at least 30-50 years and absolutely no reports from Cambodia although extensive surveys have been carried out. The Khmer Rouge during wartime is probably responsible for their demise.

5) Dugong or sea cow: Extremely endangered in the seas of Thailand. There are a few survivors but are probably doomed by excessive fishing and tourism.

6) Wild water buffalo or Asiatic buffalo: Endangered with about 50 individuals surviving in only one location: Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in western Thailand.

7) Eld’s deer: There are two sub-species (Siamensis and the Burmese) and both are extinct in the wild of Thailand.

8) Schomburgk’s deer: Extinct globally since 1935. They were endemic to the Central Plains of Thailand and the last one was killed in a temple in Samut Prakan by a village drunk in 1932. Sad fact!

9) Serow: These goat antelopes are endangered but they still survive in some mountaInous areas that are protected. Their horns are eagerly sought after and used in making knives for fighting cocks in the South.

10) Chinese goral or grey tailed goral: These goat antelopes are seriously endangered; a couple of hundred might live on mountaintops in northern Thailand.

11) Gurney’s pitta or black-breasted pitta: They are technically extinct in Thailand. There are a few individuals surviving in Khao Phra-Bang Kram Wildlife Sanctuary in Krabi.

12) Eastern Sarus crane: Extinct in Thailand for more than 50 years. They do survive in Vietnam and Cambodia but their numbers are low.

13) Marbled cat: They still survive in the thick evergreen forests of Thailand but their numbers are unknown.

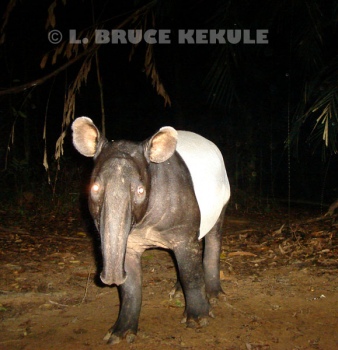

14) Asian or Malayan tapir: They still survive in the western flank of Thailand from Thung Yai Naresuan WS all the way down to Malaysia. However, they are hunted for bush meat in many places in the South.

15) Fea’s muntjac: They still survive in the western flank of Thailand from Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary all the way down to Phang Nga and Surat Thani in the South, and are hunted for meat throughout their range.

PLEASE NOTE:

While I was researching the Gurney’s Pitta on the web, I found a resort website in Krabi using my ‘first’ Gurney’s pitta photograph with out my permission. On photographs of great importance, I will now be using a new watermark covering the subject matter with my name and copyright. I regret this action but do not appreciate people stealing my photographs off the web for their own business purposes. These people have no professional ethics!

CREDIT FOR PHOTOGRAPHS

I would like to thank my good friend Kanit Khanikul for the use of his photographs of Gurney’s and Banded pittas. He certainly has one of the best collections of birds from Khao Nor Chuchi in Thailand and he has spent a lot of time and money recording avian fauna there. He should be praised for his great work!

Gurney’s Pitta – On the verge of extinction

The Gurney’s Pitta – Thailand’s rarest bird

Gurney’s Pitta in Khao Phra Bang Khram

The dark morning stillness of thick lowland rainforest of Khao Nor Chuchi, Krabi province, is broken by thumping footsteps as two humans move slowly down the trail. We carry heavy photographic equipment to a photo-blind set the previous evening, deep in the jungle. Precipitation is heavy as I set up in the hide. My helper departs quickly, conveying the message to the wildlife in the area that the intruders have left.

The ‘Emerald Pool in Khao Phra Bang Khram

Animals of the night fade into their homes and the ecosystem enters its daylight cycle. As morning light awakens the rainforest, sounds of dripping moisture begin to subside while forest birds and insects start their incessant calls as they have for millions of years.

Well hidden in the blind, I settle down, ever-vigilant for any movement on the forest floor. As the sun arches into the sky, light filters through the forest canopy in patches, illuminating the surroundings. There is a movement near the trail and a Hooded Pitta, common to this forest, hops about looking for food. The striking little blue-green bird with dark brown crown moves closer to the blind seemingly unconcerned about the looming structure.

Gurney’s pitta male

Snapping a few shots of the feathered creature but not wanting to alarm the other inhabitants of the forest, I continue to sit quietly hoping the spirits of the forest will answer my wish.

A morning rain shower passes by but quickly dissipates. As if on cue, a small black and yellow bird magically appears in front of the photo-blind, catching my eye. It’s the creature I’ve been waiting for: the Gurney’s Pitta!

Gurney’s pitta male

The little bird, perhaps sensing danger, quickly disappears into the darkness of the jungle but within minutes, is back again just long enough for only one shot with the camera.

The chance to see and photograph the Gurney’s Pitta, one of the rarest species in the world, has been my goal for several years. And this particular forest is the last known habitat for the bird which is both Thailand ‘s most endangered and a flagship species for the conservation of southern Thailand ‘s lowland rainforest.

Gurney’s pitta female

Gurney’s Pitta (Pitta gurneyi), or sometimes-called Black-breasted Pitta, is a small terrestrial forest bird endemic to Thailand and Burma . The male, with golden brown wings, bright yellow upper breast and flanks, black head and lower breast, white throat and brilliant iridescent blue crown and tail feathers, is striking indeed. The female is less colourful but, nevertheless, also very beautiful.

The species nests in spiny under-story palms laying three to four eggs but usually fledging at most two or three young. They hop about the forest floor and eat mainly insects and earthworms found amongst leaf litter but also take snails and little frogs.

Banded Pitta male

Extremely secretive, they keep as much jungle between themselves and any intruders. When danger approaches, they hop into the underbrush and disappear.

Of the world’s 31 known pittas, found from Africa to the Solomon Islands , and from Japan through Southeast Asia to New Guinea and Australia , 12 species are found in Thailand . They are Gurney’s, Giant, Banded, Hooded, Blue-winged, Blue, Blue-rumped, Eared, Mangrove, Garnet, Rusty-naped and Bar-bellied, of which the first five mentioned are found at Khao Nor Chuchi. The probable geographic origin of the Family Pittidae is in the Indo-Malayan region.

Banded Pitta female

Gurneys Pitta was first discovered in 1875 by W. Davison, a wildlife specimen collector working in Southern Burma for Allan Octavian Hume, a British civil servant working in India , and doyen of ornithology at that time. The bird was named after Humes friend, J.H. Gurney of the English county of Norfolk , and a fellow of the Zoological Society of London.

In the early 20th century, the bird was actually considered common in southern Thailand . Around the 1980s, it was thought to be extinct after no reported sightings had taken place for at least three decades. Then, in 1986, Philip Round, Thailand ‘s top birder, rediscovered the Gurney’s Pitta at Khao Nor Chuchi. It was big news for bird conservation groups and was heard around the world.

Historically, the world range of Gurney’s Pitta was a small concentrated area of lowland semi-evergreen forest along the coast and inland areas of the Thai peninsula, in the provinces of Trang, Krabi, Nakhon Si Thammarat, Surat Thani and Chumphon and Prachuap Khiri Khan. However, the once magnificent lowland tropical forest, its diversity of flora and fauna unsurpassed, has disappeared from most of those areas, due to man’s incessant greed, and his urge to destroy natural forest for the sake of agriculture and profit.

Khao Nor Chuchi, at Khao Pra-Bang Khram Wildlife Sanctuary, Khlong Thom district, Krabi, about 56 kilometres southeast of the provincial capital, is the last known site for Gurney’s Pitta in Thailand . Khao Pra-Bang Khram, with its headquarters at Ban Bang Tieo village, was established as a non-hunting area in 1987 by the Royal Forest Department (RFD), at the behest of Bangkok Bird Club (now Bird Conservation Society of Thailand-BCST), specifically in order to protect Gurney’s Pitta. It was upgraded to a wildlife sanctuary in 1993, with a total area of 183 square kilometres.

The Emerald Pool (Sa Morakot) within Khao Pra-Bang Khram Wildlife Sanctuary is a beauty spot visited by many local and foreign tourists. There are many trails open to nature explorers and bird watchers known as Thung Tieo Nature Trail Network. At least 318 different bird species have been recorded here.

The site’s alternative name, Khao Nor Chuchi, comes from the 650-metre-high conical mountain which overlooks the area. Bird photographers also come to Khao Nor Chuchi after images of the Gurney’s.

Many people, after travelling thousands of kilometres from different parts of the world, have left very disappointed after not seeing or photographing it. Gurney’s Pitta is a tough bird even to see, let alone photograph.

Although the species once occupied about 40 square kilometres of this area, most of the extreme lowlands where they live and breed were excluded from the sanctuary. As a result, forest is still being destroyed to grow rubber, oil palm and coffee, and human settlement has taken up most of the area.

Villagers still engage in poaching of animal and forest products from the reserved forest. On the day I photograph this Gurney’s Pitta, I still heard a gunshot.

Pitta numbers at Khao Nor Chuchi have declined drastically in the last two decades from an estimated 40 pairs in 1986, down to 21 pairs in 1992. This slide was due primarily to uncontrolled forest destruction, perhaps abetted by capture of the species for the black market trade in forest birds, and even for some government-run zoos.

According to BirdLife International’s Red Data there were only 11 breeding pairs and two extra males remaining in mid-2000. This year, only four to five nests have been found and sightings of individual birds have been minimal. At one nest that was abandoned, local birdwatchers found bird-nets put there by villagers who used the nets to capture the birds.

The species was also found along the coast and inland at the most southern tip of Burma but no reports of them have come from there since about 1914 and it is anybody’s guess whether it still survives. No surveys can be done due to inaccessibility of the area and danger of land mines. Tough government regulations have also kept most researchers away from the area.

BirdLife International, BirdLife Denmark , and NGOs such as BCST and the Oriental Bird Club have implemented a number of projects at Khao Nor Chuchi, in collaboration with RFDs Wildlife Conservation Division. However, these have slowed, but not halted, new settlements and further forest clearance.

Ultimately, unless the wildlife sanctuary can be expanded to encompass all remaining lowland forest, and previously cleared areas reforested, Gurney’s Pitta faces a very bleak outlook for survival. This magnificent bird could disappear before we know it and that would be a sad day for conservation in Thailand .

With just 11 breeding pairs left, the Gurney’s Pitta is very likely to be the first species to go extinct in this millennium, unless all parties concerned join hands in protecting it. On the day this male bird was photographed, a gunshot was heard.

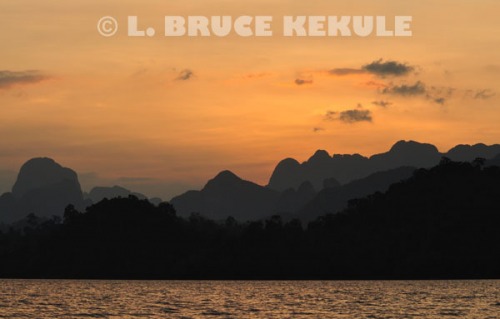

Khlong Saeng: The Lost River

One of the Kingdom’s top wildlife sanctuaries still harboring many endangered but classic Asian animals

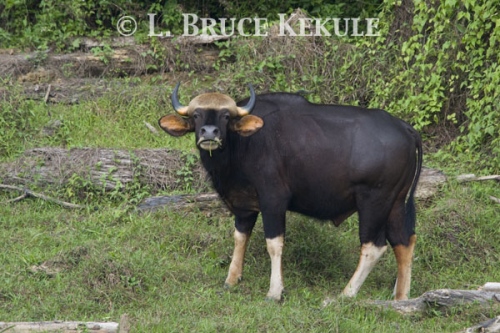

The weather is mostly clear as the sun drops behind a huge cloud close to the horizon. Light monsoon rains have begun at the end of April but hang in the mountains to the west. It has been a scorcher and heat from the day lingers over the reservoir. The light is soft and warm. About 6pm, a small herd of gaur drift out of the forest to drink at the waters’ edge and forage tender new grass. In a boat-blind about a kilometer away, I silently motor the craft closer using a battery operated trolling motor. The timing is perfect as I move in for a shot of Thailand’s magnificent but endangered wild ox.

Gaur cow in late afternoon light in Khlong Saeng

As I get closer, a mature cow feeding on an island in the lake sees something moving 100 meters offshore, and swims across to the mainland to investigate, all the time keeping her eyes locked on the strange anomaly moving in the water. Water drips from her underbelly, and her reddish-brown coat and deeply curved horns standout in the late-afternoon magic. I fire off a salvo of images hoping my camera and lens will capture this beautiful creature so late in the day. For a few brief moments, the old cow showcases Thailand’s natural heritage.

Young gaur bull

There are many beautiful forests in the South, but one in particular is truly a tribute to nature. Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary was once a magnificent natural watershed that provided water throughout the year to the inhabitants of the lowlands on the east side of the Thai Peninsula. It still harbors some very impressive animals such as elephant, gaur, tapir, serow, sambar, clouded leopard, sun bear, Great Argus (second largest of the pheasant family in Thailand), and the mighty king cobra – and the list goes on.

Gaur calf

Royal Decree encompassing 1,155 square kilometers of dense forest established Khlong Saeng in 1974. The sanctuary is the biggest in the Khlong Saeng – Khao Sok Forest Complex totaling more than 5,316 square kilometers and incorporating 12 protected areas, 11 of which are terrestrial and one with offshore islands in the Andaman Sea. Its forests are predominantly moist evergreen and most of the plants and animals are of Sundaic origin with some Indochinese species interspersed.

Curious gaur cow

Situated in the provinces of Surat Thani, Phang Nga, Ranong and Chumphon, the complex includes: Khlong Saeng, Khlong Yan, Khlong Naka, Khuan Mai Yai and Ton Pariwat wildlife sanctuaries, and Khao Sok, Kaeng Krung, Lam Son, Sri Phang Nga, Khao Lampi – Hat Thai Muang, Khao Lak – Lam Ru and Khlong Phanom national parks. They are under the responsibility of the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department (DNP) to provide protection, management and staff.

Gaur in the late afternoon

Khlong is the southern Thai word for a tributary or canal. The main tributaries of the Khlong Saeng valley include the Saeng, Ya, Yan, Ake, Mon, Ye and Mui that made-up the mighty Khlong Pasaeng. This river ran wild from the Phuket Range down to the Mae Tapi River in Surat Thani and eventually into the Gulf of Thailand. The riverine habitat teamed with flora and fauna, and the ecosystem was absolutely pristine. Tigers and leopards lived alongside many prey species like sambar, muntjac and wild pig. Elephants and gaur were fairly common. It was a magnificent wilderness at one time.

Gaur cow and her calves

But in the mid-1980s, a drastic change to the Pasaeng River was to come about. To increase Thailand’s electrical power needs, and back when building hydroelectric dams was in vogue, it was decided by the Electrical Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT), a state enterprise, and the government, to construct the Rajaprabha Dam that eventually inundated a total of 165 square kilometers (65 sq. miles) of the Khlong Saeng valley to become the Chiew Larn reservoir in 1986. The water body extends into the sanctuary for more than 50 kilometers (30 miles) but is only about two kilometers at its widest point.

Flooded forest in Khlong Saeng

Where rivers and forest previously existed, large waterways now provided easy boat access to virgin wilderness. The skeletal forms of what were once huge forest trees stand as a reminder of what disappeared beneath the flood more than a quarter of a century ago. Some trees still stand but many have come crashing down especially up-stream where decaying is severe. Millions of plants and animals perished as the floodwaters rose. The late Seub Nakhasathien, one of Thailand’s hero’s of wildlife conservation plus rangers and wildlife researchers saved hundreds of stranded fauna caught on islands. There are some 160 of them scattered throughout the reservoir when water levels are low. Some denizens were able to swim and move to higher ground but not all. It was the beginning of a new ecosystem – a large lake with a very long and complicated shoreline.

White-bellied sea eagle with a fish

Probably the most impressive scenic site in the sanctuary is the massive limestone ‘karst’ formations that were formed sometime during the mid to late Permian over 200 million years ago. It was a time of widespread mountain-building and volcanic activity. Thailand was part of Gondwanaland that was still attached to Pangaea, the ‘Supercontinent’. These colossal outcrops, some reaching as high as 960 meters (3,150 feet), look almost ‘architectural’ in design and are as impressive as the famous towers in Phang Nga Bay to the south. These configurations are the remnants of a prehistoric coral reef that once thrived here.

King cobra hunting for prey

Of all the animals in Khlong Saeng, gaur is probably the icon of wildlife in the sanctuary. These bovid are now rare in Thailand surviving only in a handful of protected areas, but they thrive fairly well. However, this only occurs around the upper reaches of Khlong Saeng and several other tributaries. The population of gaur here is estimated to be about 100 individuals and is one of the Kingdom’s best reserves for the species due to the dense moist evergreen forest.

Osprey in the mid-day heat

Breeding seems to be healthy; as many calves and young gaur of various ages have been seen in several herds I photographed at this site. Large solitary bulls keep the herd in stable breeding condition. These herbivores need huge tracts of forest free of human presence to survive. Being extremely shy, these wild cattle flee on the first sign of man. Good availability of food, water and minerals are important to their survival and the sanctuary provides these in abundance. There are still some elephants but their numbers seem to have declined. Further downstream, human activity has all but obliterated the large mammals including the tiger, which has not been seen for more than twenty years, even after extensive camera-trap surveys carried out by the research unit at the sanctuary headquarters.

Young Asian Tapir camera-trapped

Next door to Khlong Saeng is Khao Sok National Park covering 739 Square kilometers established in 1980. Khao Sok is well known around the world. The national park’s mandate in Thailand is to promote and encourage tourism into various nature sites within the protected area. After the Rajaprabha dam was completed, boats and wooden rafts were built at an alarming rate to accommodate this new business of boating visitors into the lake. Now there are hundreds of craft, many extremely noisy. Fishing was allowed and it was a free-for-all in the beginning with everyman for himself. All forms of fishing were used including explosives, electricity, nets, trap-lines and spear guns. Many areas were quickly depleted of fish, and fisherman must now venture deeper into the reservoir trying to eek out a living.

Old bull gaur camera-trapped

Actually, the Fisheries Department (FD) has a regulation in place that states ‘no fishing’ is allowed from the dam five kilometers to the limestone cliffs during the breeding season from 15th May to 15th September. This ban should extend completely into Khlong Saeng. Unfortunately, there seems to be little or any formal protection in place as boats and people come and go with no restrictions. Also, in Khao Sok, there are many rafts that have extensive facilities including a ‘karaoke’, which seems distant from nature. Every year the FD releases several species of fish into the reservoir. The ‘giant catfish’, a species found in the Mekong River, was released here and are most likely competing with other large resident fish. The FD has banned its capture but all fish are being caught for the pot, or sale to waiting ice vendors at the dock.

Dusky langur on a stump

However, a more serious problem exists that needs immediate attention before it is too late. When the Rajaprabha hydroelectric dam was finished and working on-line, EGAT passed a regulation and transferred protection duties to Khao Sok National Park. This included the complete waterway and 100 meters up into the terrestrial landscape meaning the entire water body intrudes deep into Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary for more than 50 kilometers and the mandate for its use and protection is controlled by the national park. People easily penetrate Khlong Saeng to poach, gather and fish, and the sanctuary officials have no authority on the waterway. Budgets are low and therefore, protection and enforcement is minimal. It is an extremely large loophole that needs to be fixed soon!

Gaur cow feeding on grass

EGAT, DNP and FD should join forces to find a viable solution, and take corrective steps to re-zone the reservoir. The solution is easy. About 20 kilometers into the lake at the mouth of Khlong Mon, the lake narrows down to about two hundred meters across. A rope barrier and guard post has been erected by the sanctuary but is unmanned for the most part due to the national park’s mandate. Constant overfishing and visitation to the upper reaches of Khlong Saeng over the long run will definitely have a serious impact on this sanctuary, especially gaur due to their very shy nature. Another very sensitive species is the Great Argus. These beautiful birds will abandon a breeding site if disturbed by humans. There are six hornbill and two gibbon species indicating a pristine forest. Stump-tailed macaque is the largest primate and dusky langur or leaf-monkeys are common. White-bellied sea eagle, lesser fish-eagle and osprey plus otters depend on fish and even though there is still some species in abundance, saturation fishing will eradicate most fish over time.

Sunset over the Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

The DNP’s mandate for ‘wildlife sanctuaries’ is straightforward; they have been set aside for wild species propagation, biodiversity research and habitat preservation. With hundreds and possibly thousands of people visiting Khlong Saeng every year, it is doubtful whether the sanctuary can sustain its habitat diversity over the long term. Also, trash and oil pollution from the boats is serious problem that needs attention and constant surveillance.

Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary is a beautiful but forbidding forest, and its incredible biodiversity it a tribute to the Kingdom’s natural heritage. In terms of research, very little is actually known about the interior but its future depends on many things. Most of all; the protected area should become the focus of attention so that all concerned may take a hard long look and save it for the future. Decisive and quick action in the only recourse before it is too late.

In the field:

After more than a decade of visiting forests in the East, West and North, I decided it was about time I went down South. From January 2009, I began a photographic and camera-trap program in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary. Over the course of five months, a trip every month was scheduled. On the very first outing, we arrived at our final destination after a four-hour boat ride. I jumped onto a floating raft (ranger station) not far from the headwaters of the Khlong Saeng. After a few minutes of unpacking and getting settled in, someone shouted out that an elephant was by the waters’ edge across from the ranger station in plain sight.

Young tusker elephant in Khlong Saeng

What a strange bit of luck. We immediately jumped back in the boat and crossed over to where a young tusker was feeding on bamboo leaves and occasionally taking a drink from the lake. He was alone and we could not figure out why. Possibly the herd bull or an old belligerent cow elephant had pushed him out. We will never know. This little bull was in good condition and looked fine. The next day, I was back at the same spot waiting but he did not show. The morning after, he was back. I left the next day but before we parted company, I decided to name him ‘Nong Saeng’ after the river. I thought that would be the last time I would see the little youngster.

Young bull gaur

A month later I was back at the station and the first thing I asked; where was ‘Nong Saeng? No one had seen him. Two days later about 4pm while I was traveling up-river in my boat-blind, I bumped into him again, but much farther into the reservoir. He was back by the shoreline feeding and I was elated to say the least. I stopped the boat and had a great time photographing this lively young elephant once again. He was seen a couple more times by the rangers but since then, ‘Nong Saeng’ has probably gone up into the hinterland as the monsoon rains have begun. This encounter will always create fond memories of nature’s little quirks and how things work out sometimes. Hopefully, I will get a chance to see him again next year in January when I return to continue documenting the wildlife at Khlong Saeng.