Posts Tagged ‘gaur’

Kuiburi National Park: Natural evolution in Southwest Thailand

Home to wild elephant and gaur:

Elephants and gaur just after a rain in the grassland

“Wild elephants should live here in the wild, but the forest must be restored to a state in which it is able to be a source of sufficient food. We must dedicate small plots of land throughout the forest that will serve as food sources. Moreover, elephants must be protected when roaming near the forest edge.”

His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej on July 5, 1999 said on the management of the human-elephant conflict in Kuiburi National Park

A gaur bull in the grassland

Just about every afternoon, a natural phenomenon has evolved into one of Thailand’s greatest wildlife shows. A savannah or grassland situated in Kuiburi National Park in the southwest province of Prachuap Kirikhan provides a backdrop for sighting three of the Kingdom’s majestic wild animals.

Elephants, gaur and banteng seen in daylight are rare occurrences in other protected areas around the country but not here. Due to increased attention, conservation, research, funding and better protective enforcement management, the park is now world famous as a place to see these creatures. Even a tiger was recently seen here in broad daylight.

Asiatic jackal at one of eleven waterholes

This has taken place because many people now see the important aspect and value of protecting Thailand’s natural resources for the world to see. Conservation success stories are as rare as intact ecosystems and our precious wildlife. Kuiburi has become a role model for wildlife conservation in the nation.

His Majesty the King and Her Majesty Queen Sirikit have taken a special interest in Kuiburi from the early 1970s when Their Majesties provided assistance in the construction of the Yang Chum earthen irrigation dam in Kuiburi. Through their guidance in 1979, this Royal Project when completed provided access to 32 million cubic meters of water for the lowland people.

Elephant herd in late afternoon near a waterhole

After a big flood in 1996, the dam’s height was raised two meters with His Majesty providing funding to restrain more water. This was the first dam in Thailand that used earthen material from the United States to raise dam height. Water volume was increased another 9 million cubic meters and still operates to this day providing water for farming and subsidence to the people in the province.

His Majesty was also instrumental in coaxing villagers and farmers out of Kuiburi in the early 1990s, and in 1999 the protected area was finally established as a national park encompassing an area of 969 square kilometers. A large portion of the interior had already been cleared for agriculture with pineapples as the main crop plus sugar cane, vegetables, and several pine and eucalyptus tree plantations. Many people-elephant conflicts arose to become a serious problem for all. The degradation was quite severe but the park was saved just in the nick of time due to His Majesty’s efforts.

Elephant in a waterhole cooling off

Chalerm Yoovidhya of ‘Red Bull’ fame and owner of Siam Winery, has financed many projects improving the habitat for elephants and wild cattle. His first efforts were to develop firebreaks during drought periods and build check-dams in some streams to provide water in case of forest fire.

Another very important program implemented by his team and headed by Chayapol Sornsil has also improved salt licks and the grassland that attract these huge herbivores. Other programs like helping the rangers with food and equipment for patrolling has been undertaken. Chalerm recently started the ‘Thai Gaur Conservation Group’ based just outside the park. He is also organizing a foundation to help the infrastructure, up-keep of the grasslands and other important issues like the patrol rangers.

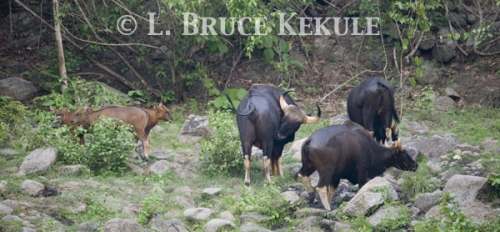

Banteng cow, mynhas and gaur in Kuiburi

Another important partner is the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Thailand who has also been very busy with many projects in Kuiburi including helping the elephant-people conflict plus doing research and camera trapping in the interior to see what has survived the onslaught of poaching and encroachment over the years. Illegal hunting still goes on but now on a very limited scale. It is a tough one to stamp out completely but under proper guidance and supervision with ‘Outreach’ programs, there is a chance for zero poaching and no encroachment over the long run. They have also been involved in the grassland, salt lick and check-dam projects.

According to Dr Robert Steinmetz with WWF, there are five confirmed tigers and probably more, plus a multitude of other carnivores and prey species. Rare animals like tapir, Fea’s muntjac, clouded leopard plus Asiatic jackals, black bear, sun bear, golden cat among others has also been camera trapped by Robert. Wayuphong Jitvijak, also with WWF, has been extremely busy coordinating with the park’s personnel and local villagers on conservation, especially with the elephants.

Elephants in an old eucalyptus plantation

The most important aspect was the establishment of the grassland just a short four years ago that was compatible with wildlife. Huge areas of invasive Guinea grass (Megathyrsus maximus var maximus) that is not suitable to wildlife were removed, and replaced with Ruzi grass (Brachiaria ruziziensis), a species that elephants, gaur and banteng can live on and propagate. More than 12,000 Rai has been developed. Major funding from the National Lottery Bureau and grass seed from the Department of Livestock in conjunction with more funding from Siam Winery and WWF has been invested.

Another man has also been a very important asset for Kuiburi. He is Boonlue Pulnil, a former superintendent here who took a vested interest in the continued existence of the park. He managed to get funding to establish 11 waterholes that now provide water for the animals especially during drought periods. He still works for the Department of National Parks (DNP) and with several NGOs and groups on improving Kuiburi’s ecosystems and the wildlife. One such group is the Foundation for the King’s Wild Elephant.

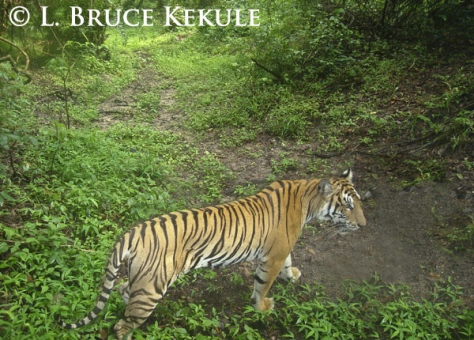

Tiger photographed near the grassland in Kuiburi

Other people have taken an interest in Kuiburi’s long-term survival. The present chief of Kuiburi, Cholathorn Chamnankid is actively involved in improving protection and enforcement with a program of wildlife conservation and zero poaching. Other dignitaries include the Governor of Prachuap Khirikan, Weera Sriwathanatrakoon, who has been at the forefront of protecting Kuiburi. General Noppadol Wathanotai, advisor to His Majesty’s Projects, Office of the Principal Private Secretary is also working with the group. Kuiburi District Chief Officer Phongphan Wichiansamut, an avid nature fan, is supporting all activities on wildlife conservation and protecting the park for the future.

In July 2012, a MOU singing ceremony between the main agencies in Kuiburi including the Royal Thai Army (First Army Area of Thailand), Border Patrol Police Bureau and Provincial Police Operation Center made a dedicated effort in the province supporting the Tenasserim Agreement at Yang Chum Dam. These conservation results are positive showing a 100 percent increase in both populations of gaur and elephants. The grassland north of the headquarters is the key.

Mixed banteng and gaur herd in the savannah

Due to its status and improvement in awareness from near extinction to herds of about 250 elephants and more than 150 gaur, the road to recovery is positive. These amazing animals are now thriving very well, mainly around the savannah. Banteng however, is still highly endangered here with just a few individuals remaining including two mature bulls and one cow sighted mixing with gaur. It is hoped there are more banteng in the interior.

The need to protect these forests and wildlife in the lower Tenasserim Range is of vital importance. In the old days before roads, Kuiburi, Practakor reserved forest and Kaeng Krachan National Park to the north was all connected by naturally occurring corridor of thick rainforest along the border with Burma by these mountains.

Some 50 years ago, Thung Plai Ngam – a hunter’s paradise – was a favorite place of the rich to go on hunting trips. It is situated behind Pranburi reservoir but is now completely void of wildlife. Back then there were crocodiles in the river and large herds of elephant, rhino, gaur and tiger were common. Kuiburi was famous for its tigers in the old days.

The grassland success in Kuiburi National Park

As humans built roads and expanded into virgin forests after wood and other resources, agriculture and villages followed and replaced the jungle. All the classic Asian animals and ecosystems were systematically wiped out in man’s eager quest to survive. It is impossible to get all this back but it is imperative that the remaining patches of forest and wildlife must be saved and protected to the full extent of the law.

One of the most important aspects of wildlife conservation is to educate the people on the importance of saving Kuiburi for future generations and the world to see. Also, to keep any expansion in the park to an absolute minimum, and make sure the rangers undertake constant patrols, and arrest and put law-breakers behind bars for long periods of time. It is a fact! With zero poaching and no encroachment, the forest and wildlife will come back over time.

It now seems that Kuiburi is a special place in Thailand, and we all should be proud of the people who are or have been involved it its continued survival. They should be commended for their efforts. It has made the difference and the Kingdom’s natural heritage has recoved from near extinction to this. Finally, constant pressure must be applied to all aspects of protecting the Kuiburi forests so generations to come will see the heroes and successes of today..!

Chasing a Wild Dream

A video about Thailand’s Amazing Wildlife in the Western Forest Complex. From wild elephants to green peafowl, this film shows the world the wildlife in the Kingdom’s protected areas, and the need to save this wonderful natural heritage for present and future generations to come.

In the heart of Southeast Asia, the Kingdom is blessed with some of the best and last remaining examples of Asian animals and ecosystems that harbor the tiger, leopard, elephant, gaur, banteng, wild water buffalo, tapir, sambar, muntjac, gibbon, green peafowl, hornbill, plus thousands of other amazing creatures and biospheres that have evolved over millions of years and show-case Mother Nature and her magnificent beauty…!

Camera trap videos in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary

Early in 2011, I set several camera traps and video units including a Bushnell Trophy Cam around a mineral deposit and water hole visited by wild animals including wild pig, banteng, sambar, tiger, gaur, peafowl and crab-eating mongoose plus more. This is a collection of video clips from the Bushnell captured over the course of one month from January to February.

Escape to Nature – Photographing rare animals

Visiting the forest during Songkran: Thailand’s New Year and water festival

Huai Kha Khaeng reveals some wild endangered Asian creatures

Indochinese tiger camera-trapped in Huai Kha Khaeng

When I was 19 years old, I arrived in Bangkok at the end of March spending a week or so in the ‘City of Angels’ enjoying the sights and sounds. This was in 1964 just as the Vietnam War was getting into high gear. Pollution was mild and the klongs were not that bad.

I remember riding around in Datsun Bluebird taxis with no air-con and watching the road flash-by between my feet. The gaping hole made me nervous but the capital was an amazing experience all stored in the old memory bank.

Banteng bull and cow at a waterhole in Huai Kha Khaeng

After the hustle and bustle of the city, Dad and I caught the train headed north to Chiang Mai. The next morning at dawn, we passed through Phrae province surrounded by misty mountains. I opened the window and the cool breeze was refreshing. I instantly fell in love with the countryside and decided that Thailand was for me.

We arrived in the northern capital just in time to celebrate Songkran water festival for the very first time. As a teenager, it was a blast. But it was still tough getting around on my motorcycle as the main object of some people especially at intersections was to kill the bike, and then completely drench the rider (me) with water and powder.

Bull gaur arrived at the same waterhole a few minutes after the banteng

Yes, downtown Chiang Mai and the surrounding countryside was a madhouse even back in ‘64’. Songkran lasted for more than seven days in the north starting a few days before April 13th and finishing up a couple of days after the 15th.

As Thailand’s northern forests and mountains provided plenty of water for the festival, there was a seemingly unlimited supply. The watersheds were still very healthy at that time. In late March – early April, the temperature was cool in the evening and warm to hot during the day.

Crested Serpent-eagle flying out of the same waterhole

Eventually I met-up with some fellow Americans and the three of them are life-long friends to this day. John C. Wilhite lll was attending classes at the newly built Chiang Mai University, and his father was a Major in the U.S. Air Force for JUSMAG (Joint US Military Advisory Group) advising Royal Thai Air Force personnel on tactics and operation of AT-28 training aircraft. Johnny and I still continue to communicate after all these years.

Wayne (Beak) Sivaslian and Ed (Mac) McDonnell with the U.S. Army were stationed in Chiang Mai. Their mission was sensitive and classified but we were close friends and still are to this day. We recently held a 40-year reunion back in the States.

Asiatic jackals at a ranger station in the interior

When Songkran rolled around, we got out the old U.S. Army deuce and a half (2 1/2 ton truck) and took off the tarp and filling the back with three or four 200-liter drums with water and ice. We then headed downtown to do battle. As we were higher up than most, we had an advantage and usually won the water fights. At the end of the day, our lips, hands and feet would turn blue and we would be shivering but boy was it fun. Finally, the police outlawed trucks with large drums of water but that did not last long.

Asiatic jackal on the run

One year, I took my family including the wife and daughter plus all the in-laws out on the town in the back of my old Series One Land Rover with no cover, doors or windows. I was the driver and had to keep my wits about me. As we were nearing Suan Dok Hospital, a drunken hooligan dipped a bucket full of dirty klong water to the brim. He then threw the entire load straight into my ribs and face with extreme force from a distance of less than a meter, and that really hurt. All he did was laugh. However, with the family in tow, I kept my cool and carried on.

Asiatic jackal on the run

That was the last time I drove an open vehicle out on the streets of Chiang Mai during the festival. I once saw a bunch of people by the Ping River with a platform and fire-fighting nozzle in a tree, and a pump down by the water’s edge (obviously from the fire department nearby). After a day, the police came around and shut them down as they had damaged several cars with the high-pressure spray.

I went running through town with the Hash House Harriers a few times but again, it was even worse with water in my ears, eyes, nose, and usually contracting a serious cold afterward. I finally decided to retire permanently from the madness.

Abstract- Asiatic jackal on the run

Some may wonder why I am talking about Songkran in this post but it is the main reason I now ‘run away to nature’ every year to enjoy peace and quiet, the birds and bees plus the refreshing coolness of the deciduous and evergreen forests I frequent. No traffic jams or crazy water-throwing people here.

This year I was granted permission to enter Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary by the Wildlife Conservation Division in the Department of National Parks (DNP) to photograph wildlife. It was a great opportunity and I made the best of it.

Jackal pair near the ranger station

Leaving Bangkok on the 11th of April, I arrived at the headquarters and met-up with the new chief Uthai Chansuk who was there to meet me. After consultations with him, I made my way into the interior with three other friends to a ranger station and settled in for a day.

A Thai friend and fellow wildlife photographer Sarawut Sawkhamkhet, has been with me on many occasions and knows this place well. He opted to sit in a permanent blind situated at a mineral lick close to the station.

Jackals chasing each other

My other two friends are Paul Thompson and Ian Edwardes, both Englishmen, and they set-up temporary blinds not far away. These two keen photographers got barking deer and a banteng bull on the very first day.

In the meantime, the rangers took me down to a platform overlooking a water hole and mineral deposit several hours walk away. We arrived at the blind about 10am and they went back to the station. I settled in for an overnight stay. I had plenty of water and food, and the weather was cool. Fortunately, my hammock fits perfectly between two trees that are part of the structure. This was April the 14th as the water festival was in full tilt.

Crested serpent-eagle taking off

The afternoon dragged on and about 2pm, a crested serpent eagle came for a drink. The raptor stayed for short while taking in copious amounts of water and then lifted off while I got a series of shots. About 5pm, as if the ‘Spirits of the Forest’ had granted my wish, a herd of banteng showed up coming straight down to the water hole for a refreshing drink. A huge bull with an enormous set of horns pushed his way through. I immediately began shooting my cameras. All of a sudden, they spooked and retreated up the hill. I thought they had scented me but this was not so.

Banteng herd at the waterhole in late afternoon

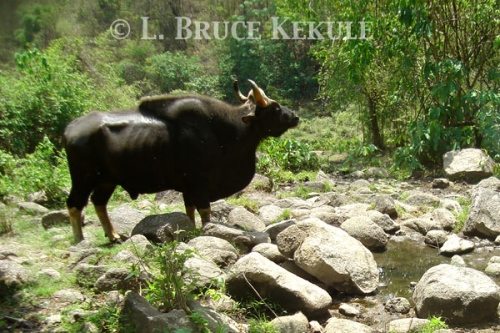

Just then, a huge mature bull gaur came down to the waterhole from the same direction as the banteng had come. Two species of large wild bovid in less than five minutes is simply amazing. This bull is very old with many rings at the base of his horns with both tips almost completely worn down. Definitely near the end of his life.

Gaur bull taking a drink at the waterhole

Dr Sompoad Srikosamatara at Mahidol University and Dr Naris Bhumpakphan at Kasetsart University estimated this solitary bull to be somewhere between 14-16 years old judging from the amount of rings. This old boy stayed at the waterhole for more than a half hour taking in his fill. He then snorted and bolted up the hill looking extremely powerful and quick on his hooves.

Lone gaur bulls will sometimes shadow a banteng or gaur herd for protection against tiger attack and poachers. They also sometimes team-up with other bulls. Simply put, more eyes, ears and noses act as security from predation.

Wild pig at the waterhole just before darkness

However, it was not my scent that had spooked the ungulates as a mature wild boar with large tusks then came for a drink just before darkness. Eventually, night set in. I had my little gas stove and boiled up some water for noodles and coffee. After eating, lightning and thunder began in the west but eventually subsided. The weather was nice and crisp, and I slept like a log.

Mineral hot spring deep in the interior of Huai Kha Khaeng

The next morning, I was up at daybreak. After a quick cup of coffee, the banteng herd from the previous day came to the waterhole again. This time they stayed for some time taking in refreshment. Funny enough, the bull had a leafy branch stuck between its left ear and horn. I of course kept shooting until they had gone. These cattle are rare in Thailand and tough to see in the wild. Banteng are a favorite wildlife subject and I felt lucky.

Sambar stag in a mineral lick in the interior

At noon the next day, the rangers and Thompson came to pick me up. Before leaving, we set camera-traps around the mineral deposit leaving them for a month. A young Indochinese tiger visited one of my cameras catching it in a broadside pose shown in the lead photo. This shot is one of my best tiger camera-trap captures ever, as it is close and in beautiful light early one morning just after Songkran.

Young sambar stag at another mineral deposit

Back at the station two Asiatic jackals that had been released by someone who had kept them in captivity were romping about. They have now made the area their home. I was able to get some exciting photographs of these two wild canids as they scavenged around the station. The pair, a male and female, once brought a deer leg from a carcass nearby and devoured it. They certainly have adapted to a life in the wild but are not afraid of humans.

Wild pig and piglets at a mineral deposit

A day later, we moved to a hot springs deep in the interior. Here, we photographed wild pig and sambar. As the rains have come early this year, insect activity is already in full swing. Thompson and I got out our macro lenses and had a great time chasing down the little creatures. We both photographed several new species for us including a lantern bug. The trip finally came to an end and we left the sanctuary with loads of new photographs showing the amazing biodiversity of this place.

Thick-billed pigeon at the hot spring

I know I have written many times about Huai Kha Khaeng in this column, but as the nation’s top wildlife sanctuary, it needs special attention and its continued survival cannot be stressed enough. More work is needed to improve protection with everything else taking a backseat like research and development. Ranger patrolling should be more consistent with revolving teams to create no loopholes for poachers and gatherers. Better budgets and personnel are the key.

Tree frogs mating in a pool on the road in the sanctuary

Thailand contains some of the most beautiful habitats and creatures in the world. The Kingdom is home to more than 70 million people, yet it supports an incredible variety of wildlife. However uncertain the future of the country’s wild flora and fauna may be, their presence today remains a spectacular, intriguing and mystical natural wonder.

Orb web spider at a ranger station deep in the interior

Lantern bugs at the same ranger station

*************************

Gaur – Majestic Wild Forest Ox

WILD SPECIES REPORT

Rare mammal and the largest bovid in the world

Endangered wild cattle close to extinction

Gaur cow in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

About 20 million years ago, the first ungulates evolved from small, hornless deer-like ancestors. Cattle, sheep, antelopes and goats are grouped together in the family Bovidae, and the most common hoofed grazing animal seen today. Sometime during the Pleistocene Epoch 1.8 million years ago, the genus Bos evolved in Asia and spread to Europe, Africa and eventually North America. Gaur Bos gaurus is a descendent of Bos Bibos, a wild cattle that lived on the great plains of Asia. Saber-toothed cats were one of the top carnivores at the time, and evolved alongside the ancient herbivores.

Gaur calf in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

Gaur, the largest bovid in the world, is threatened with extinction and deserves much greater attention. The tiger and elephant have taken most of the conservation spotlight but gaur, like all the other wild animals need just as much protection, research and concern. Unfortunately, these wild forest ox continue to vanish from the wilderness areas in the Kingdom. After years of poor protective management and neglect, poaching and trophy hunting, plus a disappearing habitat suitable for these enormous creatures once found throughout Thailand, is the main reason for the decline.

Over their entire range, they are classified as internationally threatened. But not all is lost as gaur still survive quite well in a few of Thailand’s top protected areas in fair numbers, and where there are true safe havens, the species has actually made a come back. It is now estimated that more than a 1,000 individuals remain in Thai forests. This number is up from the 500 recorded in Dr Boonsong Legakul and Jeffery McNeeley’s book Mammals of Thailand published in 1977. Dr Sompoad Srikosamatara and Varavudh Suteethorn published a paper in the Siam Society’s Natural History Bulletin in 1995 about gaur and banteng. Their estimate then was about 1000 gaur were surviving so the number is basically stable and most likely on the increase.

Gaur herd at a mineral deposit in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary

In Southeast Asia and India, gaur is found in scattered and splintered habitats. Other large wild bovine are banteng and wild water buffalo of Southeast and Southern Asia, the yak of Central Asia, the cape buffalo of Africa, and the bison of North America and Europe. In recent times, the number of these wild creatures has dwindled as humans continue to hunt them for meat and trophies, and destroy and encroach on their habitat in some places. The American bison came close to extinction but was saved in the nick of time. Thousands of wild bison now survive due to conservation efforts initiated by many people including the late U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt.

Gaur is Thailand’s second largest terrestrial animal after the elephant and tends to inhibit deep mountainous terrain far from humans. They survive in dry and moist evergreen forest plus mixed deciduous forests and therefore, have fared better than their cousin, the banteng that live in more open lowland forest. Gaur occasionally mixes with banteng that has been documented in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, Uthai Thani province. Gaur will also shadow elephant herds using the same trails made by the larger mammals.

Gaur herd in Khlong Saeng

My favorite photographic wildlife subject is gaur. In Thailand, these majestic ungulates can still be found in the following places: the Western Forest Complex and Kaeng Krachan Forest Complex, both in the west; the Khao Ang Rue Nai Forest Complex in the east; the Dong Payayen – Khao Yai Forest Complex and the Phu Khieo – Nam Nao Forest Complex, both in the Northeast; and down south in the Khlong Saeng – Khao Sok Forest Complex. Due to the serious instability in the deep south, very few surveys have been carried out and there is no consensus on gaur but they do survive in the Hala-Bala Forest Complex situated along the border with Malaysia. It is doubtful if any gaur survive in the North but the Omkoi – Mae Tuen Forest Complex might have few left.

Gaur has a keen sense of smell and hearing, and is always alert for danger. As a result, they can be tough to spot in the dense forests of Asia. However, luck does come sometimes, and the following accounts describe the few times I have had the great fortune to observe these magnificent beasts in the wild.

Gaur bull camera-trapped at a mineral lick in Huai Kha Khaeng

My first photographic encounter with gaur in 1986 was at the beginning of my career as a wildlife photographer deep in the interior of Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. A natural deposit or mineral lick several hours walk from the road attracts many animals – gaur, banteng, elephant, sambar and muntjac come for the life-giving minerals, plus tiger, leopard and Asian wild dog hunt for prey. The balance of nature runs in harmony where “eat or be eaten” is the rule. I was extremely lucky and photographed two mature bull gaur that arrived late one afternoon as the sun was setting. The old bull on the front cover of my first book ‘Wildlife in the Kingdom of Thailand’ stayed at the waterhole for quite sometime and I shot several rolls of film. This place has always been special to me.

A year later, I began visiting Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary along the western border with Burma specifically to photograph gaur. In 1985, a herd of more than 50 individuals was seen from a helicopter by park officials on the huge grassland in the center of the sanctuary. Thung Yai is a tough place to work as many mining trucks plus off-road 4X4 enthusiasts with big tires and jacked-up truck chassis have abused the road into the sanctuary for many years. Deep ruts in many areas make travel along the road difficult even for normal off-road vehicles. The rangers have a real rough time patrolling this sanctuary.

Young gaur bull in Khlong Saeng

On one of my many trips to Thung Yai, and after many grueling hours of travel, and then a couple hours’ walk to a mineral lick in the sanctuary, I set-up a photographic blind along the forest perimeter. Late in the afternoon, two bachelor bulls entered and drank from the spring at the top end. I managed to get some good photographs as they went about their business. One bull snorted at our position as I had placed fresh gaur droppings in front of the blind, and I believe he was just letting us know who he was. Both bulls then departed peacefully and I was elated to say the least. It is estimated that more than 100 individuals thrive in Thung Yai.

In October 2008, I began a camera-trap program and set several units at a mineral lick visited by gaur and elephant in Kaeng Krachan National Park in Phetchaburi province, southwest Thailand. A month later, I visited the park and collected the cameras. A herd of gaur had come to the deposit including several cows and their offspring. It seemed as if the camera had spooked them initially, but the herd came back again the next day and a long series of captures was obtained. There are about 70 of these beautiful creatures thriving and breeding in this protected area.

Over in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in the west during December 2008, I also set some digital camera-traps at a water hole, and after one month, two gaur bulls visited the waterhole. I also sat by the river in a photo-blind across from another mineral lick and photographed a large herd of gaur that had come for the minerals and lush grass. It is estimated that 350 gaur survive in this sanctuary. Better protective measures have allowed gaur to breed profusely and this World Heritage Site lives up to its name. Predators like tiger and wild dogs capable of taking on gaur, also thrive here. In the whole of the Western Forest Complex, it is estimated that more than 500 individuals live in scattered areas covering some 15,000 square kilometers.

Gaur cow camera-trapped at a mineral lick in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Early this year while photographing wildlife in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Surat Thani province down south, I had an amazing journey of discovery. Deep in the protected area, gaur is still thriving quite well. I set camera-traps in the sanctuary and managed to capture a very old bull gaur and several herds at many locations. A close look at the photograph shows seriously worn hooves on his hind feet. He is definitely past his prime and would not be a contender for female gaur in heat. With poor traction, he could not fight the younger bulls with stronger hooves and horns.

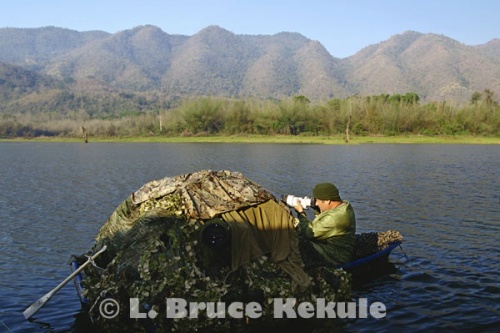

I also toured the flooded forests of Khlong Saeng and Khlong Ya rivers created by the Chiew Larn or Ratchaprapra Dam using a boat-blind and silent electric trolling motor. I was able to approach many herds and individuals over a four-month period. In every herd, there were young calves and yearlings indicating a healthy breeding population. Most of the mature bulls have become nocturnal due to past and present poaching pressure in the reservoir. In the Khlong Saeng – Khao Sok forest complex, it is estimated that more than 100 gaur are thriving.

In Kui Buri National Park, Prachuap Kirikan province, gaur has definitely made a come back due to increased awareness by the park staff plus financial support extended to help the rangers. It is now estimated that the population of gaur is about 70 individuals. Khun Chalerm Yoovidhya, MD of the Huai Hin Hills Vineyard and Siam Winery has taken a special interest in gaur at Kui Buri. Working with the park officials, he has funded many projects to help these creatures by sending volunteers to plant grass in selected areas to propagate grasslands, and setting up salt licks and check dams to attract the herbivores. Other projects initiated by Khun Chalerm include selling wildlife photographs and paintings at the vineyard to help the park rangers with food, clothing and equipment giving them more incentive to patrol the forest. Over time, other areas will put on the list for special help to protect Thailand’s natural heritage from the damaging effect of human poaching and intervention.

Gaur spooked by camera-trap in Kaeng Krachan

In the northwest section of Thap Lan National Park, my very close friend Gate Glomchum who worked for the Petroleum Authority of Thailand (PTT) as chief reforestation officer (retired) did some amazing things during his career as a reforester. Prior to 1996, a 10,000 rai area in Wang Nam Kheaw was completed degraded by a logging concession and squatters. Under his management and following a mandate set by His Majesty the King, this forest was replanted and the people were moved out. Today, this forest has completely grown-over, and there is elephant, gaur and tiger plus many other classic Asian species living in total harmony with nature. Other areas in Thailand also reforested under his supervision have had similar success.

Over in Khao Phang Ma just outside the eastern part of Khao Yai National Park, a national forest reserve was reforested by Wildlife Fund Thailand (WFT) and Khun Suthirat Yoovidhya (Director of CSR) of Red Bull-Thailand fame. Gaur moved back into this forest from Khao Yai after protective measures increased. There are about 50 gaur at this location and is probably the only place in Thailand where gaur live outside a protected area. Many projects like helping the rangers, setting-up salt licks and check dams have also been funded by Khun Suthirat under the ‘Red Bull Spirit’ program that is on-going. A couple of years ago, WFT shutdown all conservation operations due to internal conflicts but the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP) took over responsibility of the reserve. They should be commended, and it is reassuring that some people are serious about conserving the Kingdom’s natural heritage.

Gaur herd camera-trapped at a mineral lick in Kaeng Krachan

In the long run, the importance of protecting a prey species like gaur should be the number one priority for the government. The DNP need to increase budgets and personnel to look after these forests and animals. Thailand remains one of the best places for the survival of gaur in Southeast Asia. Protection, conservation awareness, education and monetary support are the keys to the future of these magnificent creatures of nature, and it is hoped they will continue to live in their natural habitat far from the destructive forces of man.

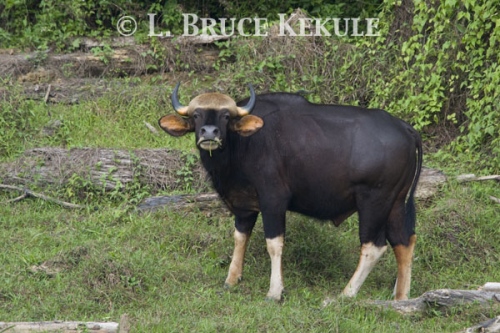

Ecology and Behavior

Gaur is the largest bovid in the world with a distinctive dorsal ridge and a large dewlap, forming a very powerful appearance. A fully mature bull stands about 1.6-1.9 meters at the shoulder and average weight of a big bull is 900 kilograms on up to a ton. Cows are only about 10cm shorter in height, but are more lightly built and weigh 150 kilograms less. These even-toed ungulates have stout limbs with white or yellow stockings from the knee to the hoof. The tail is long and the tip is tufted. Newborns are a light golden color, but soon darken to coffee or reddish brown. Old bulls and cows are jet black but south of the Istamas of Kra, many take on a reddish hue.

All bovine share common features, such as strong defensive horns that never shed on males and females, as well as teeth and four-chambered stomachs adapted for chewing and digesting grass. Their long legs and two-toed feet are designed for fast running and agile leaping to escape predators. They are gregarious animals, staying in herds of six to 20, or more.

Due to their formidable size and power, gaur has few natural enemies. Leopards and Asian wild dog packs occasionally attack unguarded calves or unhealthy animals, but only the tiger has been reported to kill a full-grown adult. Gaur grazes on grass but also browse edible shrubs, leaves and fallen fruit, and usually feed through the night. They also visit mineral licks to supplement their diet. During the day, they will rest-up in deep shade.

There are three separate sub-species of gaur: Bos gaurus gaurus of India and Nepal, Bos gaurus readi of Indochina and Bos gaurus hubbacki of Southern Thailand and Malaysia. However, in 1983, the zoological classification of both the Indochinese and Southern gaur was changed to Bos gaurus laosiensis. In 1993, Pleistocene fossil evidence of Bos gaurus grangeri, an ancient sub-species, was uncovered by G.B. Corbet and J.E. Hill in Sichuan province, China.

Khlong Saeng: The Lost River

One of the Kingdom’s top wildlife sanctuaries still harboring many endangered but classic Asian animals

The weather is mostly clear as the sun drops behind a huge cloud close to the horizon. Light monsoon rains have begun at the end of April but hang in the mountains to the west. It has been a scorcher and heat from the day lingers over the reservoir. The light is soft and warm. About 6pm, a small herd of gaur drift out of the forest to drink at the waters’ edge and forage tender new grass. In a boat-blind about a kilometer away, I silently motor the craft closer using a battery operated trolling motor. The timing is perfect as I move in for a shot of Thailand’s magnificent but endangered wild ox.

Gaur cow in late afternoon light in Khlong Saeng

As I get closer, a mature cow feeding on an island in the lake sees something moving 100 meters offshore, and swims across to the mainland to investigate, all the time keeping her eyes locked on the strange anomaly moving in the water. Water drips from her underbelly, and her reddish-brown coat and deeply curved horns standout in the late-afternoon magic. I fire off a salvo of images hoping my camera and lens will capture this beautiful creature so late in the day. For a few brief moments, the old cow showcases Thailand’s natural heritage.

Young gaur bull

There are many beautiful forests in the South, but one in particular is truly a tribute to nature. Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary was once a magnificent natural watershed that provided water throughout the year to the inhabitants of the lowlands on the east side of the Thai Peninsula. It still harbors some very impressive animals such as elephant, gaur, tapir, serow, sambar, clouded leopard, sun bear, Great Argus (second largest of the pheasant family in Thailand), and the mighty king cobra – and the list goes on.

Gaur calf

Royal Decree encompassing 1,155 square kilometers of dense forest established Khlong Saeng in 1974. The sanctuary is the biggest in the Khlong Saeng – Khao Sok Forest Complex totaling more than 5,316 square kilometers and incorporating 12 protected areas, 11 of which are terrestrial and one with offshore islands in the Andaman Sea. Its forests are predominantly moist evergreen and most of the plants and animals are of Sundaic origin with some Indochinese species interspersed.

Curious gaur cow

Situated in the provinces of Surat Thani, Phang Nga, Ranong and Chumphon, the complex includes: Khlong Saeng, Khlong Yan, Khlong Naka, Khuan Mai Yai and Ton Pariwat wildlife sanctuaries, and Khao Sok, Kaeng Krung, Lam Son, Sri Phang Nga, Khao Lampi – Hat Thai Muang, Khao Lak – Lam Ru and Khlong Phanom national parks. They are under the responsibility of the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department (DNP) to provide protection, management and staff.

Gaur in the late afternoon

Khlong is the southern Thai word for a tributary or canal. The main tributaries of the Khlong Saeng valley include the Saeng, Ya, Yan, Ake, Mon, Ye and Mui that made-up the mighty Khlong Pasaeng. This river ran wild from the Phuket Range down to the Mae Tapi River in Surat Thani and eventually into the Gulf of Thailand. The riverine habitat teamed with flora and fauna, and the ecosystem was absolutely pristine. Tigers and leopards lived alongside many prey species like sambar, muntjac and wild pig. Elephants and gaur were fairly common. It was a magnificent wilderness at one time.

Gaur cow and her calves

But in the mid-1980s, a drastic change to the Pasaeng River was to come about. To increase Thailand’s electrical power needs, and back when building hydroelectric dams was in vogue, it was decided by the Electrical Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT), a state enterprise, and the government, to construct the Rajaprabha Dam that eventually inundated a total of 165 square kilometers (65 sq. miles) of the Khlong Saeng valley to become the Chiew Larn reservoir in 1986. The water body extends into the sanctuary for more than 50 kilometers (30 miles) but is only about two kilometers at its widest point.

Flooded forest in Khlong Saeng

Where rivers and forest previously existed, large waterways now provided easy boat access to virgin wilderness. The skeletal forms of what were once huge forest trees stand as a reminder of what disappeared beneath the flood more than a quarter of a century ago. Some trees still stand but many have come crashing down especially up-stream where decaying is severe. Millions of plants and animals perished as the floodwaters rose. The late Seub Nakhasathien, one of Thailand’s hero’s of wildlife conservation plus rangers and wildlife researchers saved hundreds of stranded fauna caught on islands. There are some 160 of them scattered throughout the reservoir when water levels are low. Some denizens were able to swim and move to higher ground but not all. It was the beginning of a new ecosystem – a large lake with a very long and complicated shoreline.

White-bellied sea eagle with a fish

Probably the most impressive scenic site in the sanctuary is the massive limestone ‘karst’ formations that were formed sometime during the mid to late Permian over 200 million years ago. It was a time of widespread mountain-building and volcanic activity. Thailand was part of Gondwanaland that was still attached to Pangaea, the ‘Supercontinent’. These colossal outcrops, some reaching as high as 960 meters (3,150 feet), look almost ‘architectural’ in design and are as impressive as the famous towers in Phang Nga Bay to the south. These configurations are the remnants of a prehistoric coral reef that once thrived here.

King cobra hunting for prey

Of all the animals in Khlong Saeng, gaur is probably the icon of wildlife in the sanctuary. These bovid are now rare in Thailand surviving only in a handful of protected areas, but they thrive fairly well. However, this only occurs around the upper reaches of Khlong Saeng and several other tributaries. The population of gaur here is estimated to be about 100 individuals and is one of the Kingdom’s best reserves for the species due to the dense moist evergreen forest.

Osprey in the mid-day heat

Breeding seems to be healthy; as many calves and young gaur of various ages have been seen in several herds I photographed at this site. Large solitary bulls keep the herd in stable breeding condition. These herbivores need huge tracts of forest free of human presence to survive. Being extremely shy, these wild cattle flee on the first sign of man. Good availability of food, water and minerals are important to their survival and the sanctuary provides these in abundance. There are still some elephants but their numbers seem to have declined. Further downstream, human activity has all but obliterated the large mammals including the tiger, which has not been seen for more than twenty years, even after extensive camera-trap surveys carried out by the research unit at the sanctuary headquarters.

Young Asian Tapir camera-trapped

Next door to Khlong Saeng is Khao Sok National Park covering 739 Square kilometers established in 1980. Khao Sok is well known around the world. The national park’s mandate in Thailand is to promote and encourage tourism into various nature sites within the protected area. After the Rajaprabha dam was completed, boats and wooden rafts were built at an alarming rate to accommodate this new business of boating visitors into the lake. Now there are hundreds of craft, many extremely noisy. Fishing was allowed and it was a free-for-all in the beginning with everyman for himself. All forms of fishing were used including explosives, electricity, nets, trap-lines and spear guns. Many areas were quickly depleted of fish, and fisherman must now venture deeper into the reservoir trying to eek out a living.

Old bull gaur camera-trapped

Actually, the Fisheries Department (FD) has a regulation in place that states ‘no fishing’ is allowed from the dam five kilometers to the limestone cliffs during the breeding season from 15th May to 15th September. This ban should extend completely into Khlong Saeng. Unfortunately, there seems to be little or any formal protection in place as boats and people come and go with no restrictions. Also, in Khao Sok, there are many rafts that have extensive facilities including a ‘karaoke’, which seems distant from nature. Every year the FD releases several species of fish into the reservoir. The ‘giant catfish’, a species found in the Mekong River, was released here and are most likely competing with other large resident fish. The FD has banned its capture but all fish are being caught for the pot, or sale to waiting ice vendors at the dock.

Dusky langur on a stump

However, a more serious problem exists that needs immediate attention before it is too late. When the Rajaprabha hydroelectric dam was finished and working on-line, EGAT passed a regulation and transferred protection duties to Khao Sok National Park. This included the complete waterway and 100 meters up into the terrestrial landscape meaning the entire water body intrudes deep into Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary for more than 50 kilometers and the mandate for its use and protection is controlled by the national park. People easily penetrate Khlong Saeng to poach, gather and fish, and the sanctuary officials have no authority on the waterway. Budgets are low and therefore, protection and enforcement is minimal. It is an extremely large loophole that needs to be fixed soon!

Gaur cow feeding on grass

EGAT, DNP and FD should join forces to find a viable solution, and take corrective steps to re-zone the reservoir. The solution is easy. About 20 kilometers into the lake at the mouth of Khlong Mon, the lake narrows down to about two hundred meters across. A rope barrier and guard post has been erected by the sanctuary but is unmanned for the most part due to the national park’s mandate. Constant overfishing and visitation to the upper reaches of Khlong Saeng over the long run will definitely have a serious impact on this sanctuary, especially gaur due to their very shy nature. Another very sensitive species is the Great Argus. These beautiful birds will abandon a breeding site if disturbed by humans. There are six hornbill and two gibbon species indicating a pristine forest. Stump-tailed macaque is the largest primate and dusky langur or leaf-monkeys are common. White-bellied sea eagle, lesser fish-eagle and osprey plus otters depend on fish and even though there is still some species in abundance, saturation fishing will eradicate most fish over time.

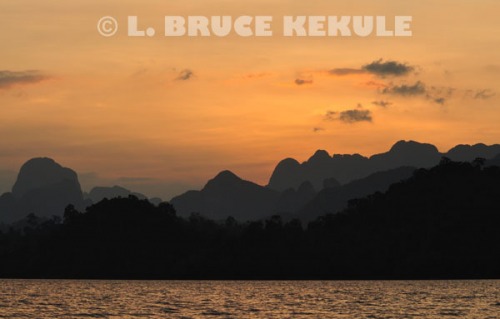

Sunset over the Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

The DNP’s mandate for ‘wildlife sanctuaries’ is straightforward; they have been set aside for wild species propagation, biodiversity research and habitat preservation. With hundreds and possibly thousands of people visiting Khlong Saeng every year, it is doubtful whether the sanctuary can sustain its habitat diversity over the long term. Also, trash and oil pollution from the boats is serious problem that needs attention and constant surveillance.

Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary is a beautiful but forbidding forest, and its incredible biodiversity it a tribute to the Kingdom’s natural heritage. In terms of research, very little is actually known about the interior but its future depends on many things. Most of all; the protected area should become the focus of attention so that all concerned may take a hard long look and save it for the future. Decisive and quick action in the only recourse before it is too late.

In the field:

After more than a decade of visiting forests in the East, West and North, I decided it was about time I went down South. From January 2009, I began a photographic and camera-trap program in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary. Over the course of five months, a trip every month was scheduled. On the very first outing, we arrived at our final destination after a four-hour boat ride. I jumped onto a floating raft (ranger station) not far from the headwaters of the Khlong Saeng. After a few minutes of unpacking and getting settled in, someone shouted out that an elephant was by the waters’ edge across from the ranger station in plain sight.

Young tusker elephant in Khlong Saeng

What a strange bit of luck. We immediately jumped back in the boat and crossed over to where a young tusker was feeding on bamboo leaves and occasionally taking a drink from the lake. He was alone and we could not figure out why. Possibly the herd bull or an old belligerent cow elephant had pushed him out. We will never know. This little bull was in good condition and looked fine. The next day, I was back at the same spot waiting but he did not show. The morning after, he was back. I left the next day but before we parted company, I decided to name him ‘Nong Saeng’ after the river. I thought that would be the last time I would see the little youngster.

Young bull gaur

A month later I was back at the station and the first thing I asked; where was ‘Nong Saeng? No one had seen him. Two days later about 4pm while I was traveling up-river in my boat-blind, I bumped into him again, but much farther into the reservoir. He was back by the shoreline feeding and I was elated to say the least. I stopped the boat and had a great time photographing this lively young elephant once again. He was seen a couple more times by the rangers but since then, ‘Nong Saeng’ has probably gone up into the hinterland as the monsoon rains have begun. This encounter will always create fond memories of nature’s little quirks and how things work out sometimes. Hopefully, I will get a chance to see him again next year in January when I return to continue documenting the wildlife at Khlong Saeng.