Wildlife Candid Camera – Infrared cameras ‘trap’ Thailand’s elusive wildlife

Wildlife Candid Camera – Infrared cameras ‘trap’ Thailand’s elusive wildlife

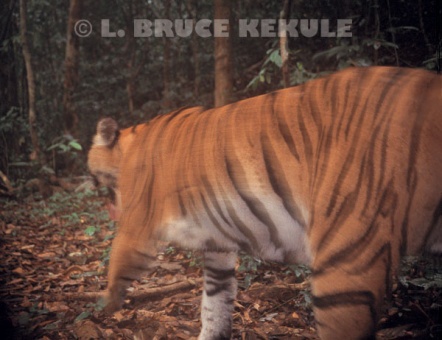

Indochinese tiger camera trapped in Sai Yok National Park

One evening as the shadows were melting into darkness in the jungle of Sai Yok National Park, an Indochinese tiger Panthera tigris corbetti was meandering up to a forest pool for his evening drink. At the planned position, a camera-trap mounted on a dead tree tripped a photograph of the cat, causing it to bound into a bamboo thicket. The tiger could not of course have understood exactly what had just taken place. Instinct triggered its reaction to the flash and the camera’s mechanical click. Taking a photograph of a tiger in the wild is a very daunting task but the wizardry of modern electronics has made the job much easier.

Gaur herd caught at a mineral deposit in Kaeng Krachan National Park

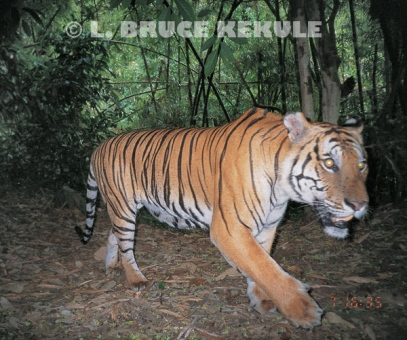

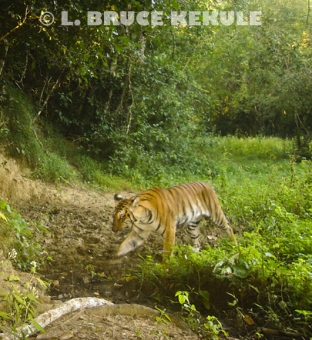

A few days later and just two kilometers away, another tiger pads slowly through the forest topping a 600-meter-high ridge in late afternoon. Its senses are on high alert for any movement or sound that could lead to its next meal. A passive infrared camera-trap set on a wildlife trail catches the tiger as it passes through an invisible motion-detection field. The time and date is recorded and the wildlife photographer has just triumphantly photographed one of Thailand’s rarest mammals in the wild – without even being there at the time; a rare candid wildlife photograph set off by the subject itself.

Mother and cub in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary

Far away in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Western Thailand, a mother leopard guides her young cub to a sambar kill. The carcass is ripe after a few days but still good for a full meal. In early-morning darkness the leopards trigger an active infrared SLR camera and strobe strategically positioned close to the dead deer. When the film was processed, I saw two feeding leopards – a mother and its cub. The female is yellow but the young one is black. Photographs of the notoriously elusive leopard would be far rarer if not for modern technology.

The history of camera traps goes back more than a hundred years. In 1906, pioneer wildlife photographer George Shiras III used a flashlight camera with trip wires to photograph wild animals. His equipment was very heavy and very complicated to use, with the lens aperture being very difficult to anticipate. Two other men experimented with camera traps activated by pressure-plates: F.M. Chapman in 1927 and F.W. Champion in 1928. Their primitive traps produced many superb black-and-white photographs that thrilled magazine and book readers at the time.

Banteng herd at a waterhole in Huai Kha Khaeng

For the last four decades or so, researchers and biologists to collect data on wildlife and also to investigate the secretive and nocturnal lives of such rare and endangered species as the tiger and leopard use camera traps. Beyond glamorous predators, species such as wild cattle, deer and pig are also, without discrimination, recorded to reveal such useful information as relative abundance and activity patterns. Camera trapping can lead to important scientific databases.

The units are most often attached to a tree, usually half a meter above the ground and three to four meters away from water holes, mineral licks, wildlife trails, forest roads or stream beds. The time and date is imprinted on each frame for scientific research.

An American hunter whose goal was to survey designed one of the first camera traps utilizing infrared technology and scout possible locations for big game like deer and bear. These active infrared sensors manufactured by TrailMaster.com in Kansas used a separate transmitter and receiver connected to a small ‘point-and-shoot’ camera which is triggered when the beam between the two units is interrupted by any moving object. A major drawback of active systems is that even an insect momentarily blocking the sensor will stimulate a photograph of seemingly empty forest. Active infrared camera traps are best suited to conditions that are dry with minimal insect activity. Further, three separate units are quite complicated to set up and maintain.

Problems with active infrared systems caused a researcher in Texas to ask a friend to develop a passive infrared camera trap, leading to the establishment of CamTrakker.com in Georgia. Passive camera-traps are a self-contained unit with the camera, batteries and sensing electronics sealed in a box. The sensor detects motion. The chief advantage of the passive system is the ease of a single unit installation with no alignment or external wires.

Asian leopard feeding on a sambar carcass in Huai Kha Khaeng

Passive infrared camera traps, which can work for one month or more between battery changes, have proven the most utilitarian for both researchers and wildlife photographers. The relatively high cost of commercial units is the major drawback, particularly to budget-strapped researchers in developing countries.

Both TrailMaster and CamTrakker have steadily improved their equipment over the years. Other companies have now joined the competition, bringing prices for entry level units down to about US$250 (Top-of-the-line models are about US$500 and CamTrakker offers a digital model that costs US$1,200).

Throughout my early years of wildlife photography, the thought of camera trapping had frequently crossed my mind. Finally, with many years of mechanical experience, I decided to build my own camera-traps. Using existing units as a model, I built a passive infrared camera-trap housed in a 6” x 6” tig-welded aluminum alloy box with a removable front cover. The camera-trap as an enclosed unit that is fixed to a tree using two stainless steel lag bolts contained within the box. A small bag of dessicant (silica gel) is set inside to protect the delicate electronics and camera from moisture, and the front cover is hermetically sealed using silicon sealant and stainless steel screws. The unit is elephant-proof that is very important in the forests I work in. Elephants destroy plastic camera-traps.

Tuskless bull elephant in Kaeng Krachan

Out of my home workshop, I was able to make these custom-built cameras for way less than half the price of imported commercial units. My very close friend Yutdhana Anantavara from Chiang Mai modified the cameras and installed the infrared electronic systems. This early work really helped me onto the road to successful home-made camera traps.

Feral cat camera trapped at my home in Chiang Mai

The first batch of prototype units employed several brands of ‘point-and-shoot’ cameras and different experimental housings. To evaluate each camera’s quality and reliability, I intensively tested each on the domestic cats that regularly walked on top of a wall behind my machine shop. Various films were tested but slide film at 400 ISO proved to produce the highest quality image.

My 1st camera trapped tiger in Sai Yok

To field test the new gear I took a trip to Sai Yok National Park in western Thailand. All of the cameras were placed along wildlife trails, waterholes and mineral licks. Over several months, the film was collected and developed. I was ecstatic when I saw two different tigers, an elephant, serow, muntjac, stumped-tailed macaque, bear, porcupine, water monitor, jungle fowl and wild pigs. The omnivores were the most frequently photographed and probably the tiger’s main prey species. A totally unexpected bonus was photographs of a few poachers.

Serow male camera trapped in Kaeng Krachan NP

Numerous camera trap surveys have been conducted in many of Thailand’s forests. A 2001 survey produced a photograph of a Siamese crocodile in Kaeng Krachan National Park. The croc was caught in broad daylight on a sandbar along the river. Park staff set cameras for a month along the Phetchaburi River. The amazing discovery of this very rare reptile has prompted more investigation into this endangered species. In 2003, I camera trapped a crocodile in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary.

Wild Siamese crocodile camera trapped in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

To analyze wildlife in a given area, researchers use two main techniques: a trail-based survey (where cameras are randomly placed along wildlife trails and roads covering 100 to 300 square kilometers) and a more intensive plot-based method. A smaller plot is chosen (usually 40-50 sq. kilometers) and a camera is placed in each one-kilometer grid. An area can eventually be exhaustively surveyed – the duration depending on the number of cameras used – to prove the presence or absence of tigers and other animals. The data then can be used for conservation management of the protected area.

Indochinese tiger abstract in Kaeng Krachan

Camera traps can reveal very disturbing information. Extensive surveys around Khao Yai National Park indicate that only two tigers survive. The patterns of tigers are as unique as human fingerprints so it is essential to get photos of both sides of each animal so that individuals can be identified. Researchers often set cameras on either side of a trail to capture both sides simultaneously. Khao Yai might have more tigers but the fact that only two individuals are confirmed is depressing. As of 2005, no tigers have been seen in intensive surveys carried out by Kate Jenks from the Smithonian Institute.

Indochinese tiger camera trapped abstract

Poachers have also been camera trapped here. Usually they walk obliviously past the camera but they sometimes damage or steal cameras. Elephants also destroy cameras, tearing the plastic commercial housings off the tree and smashing them or lobbing them into the bush. A Royal Forest Department researcher at Hala-Bala Wildlife Sanctuary in the deep south of Thailand found a unit damaged by elephants, but the camera was still working and developed the film. The last frame shows a very close view of an elephant’s trunk! Some researchers have built stronger steel boxes to protect the plastic units.

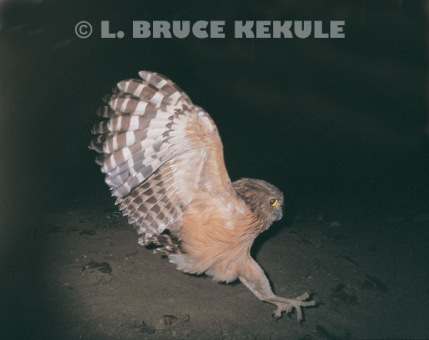

Buffy fish-owl landing by the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan NP

My aluminum-cased camera-traps firmly bolted to a tree have survived many inquisitive elephants. However, they can be stolen or vandalized by determined people who do not want their photo taken. In May of 2005, I lost three cameras near the headwaters of the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan National Park. Forest fires in the dry season destroy cameras. Insects will invade the interior of imperfectly sealed units, playing havoc with their operation. High humidity in the rainforest also damages electrical circuitry, cameras, film and batteries not protected by a well sealed unit and a small bag of moisture absorbing silica gel.

Infrared camera trapping has undoubtedly become a uniquely useful tool for conservation biologists. This ‘candid camera’ is also a blessing for wildlife photographers wanting images of rare and endangered animals. Who knows? In the future, a camera-trap could photograph a species new to science. I’m always excited when I get camera-trap film back from the lab. But the digital age had arrived. Film is being slowly phased out and digital cameras have now overtaken the market dominating it.

Asian Leopard hunting on old logging road in Kaeng Krachan NP

***************************************************************************************************

Wildlife Candid Camera: The Digital Age has arrived

LBK camera trap attached to a tree using Python locking cable

LBK camera trap with Yeticam board and Sony W7 in custom aluminum case

Digital camera traps have now become the new sensation, especially the home-brew (self-made) market. It is now a huge business with a few companies vying for market share. The most predominant are Snapshotsniper.com and Yeticam.com, and they offer parts (sensor boards, lens, battery packs, cases, etc.) to the home builder.

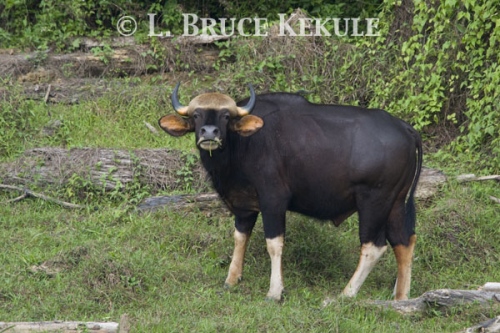

Very old bull gaur at a waterhole in Huai Kha Khaeng WS

My friend Chris Wemmer, the ‘Cameratrap Codger’, was the first person to tell me about a new company in the US producing infrared circuit boards and other accessories for the home-brew camera trap market. The company is Pixcontroller.com. Unfortunately, they no longer offer parts but now sell completed units with digital camera and video.

Mature bull gaur at water hole

As a wildlife photographer, I decided to produce my own digital camera traps using passive infrared circuit boards acquired from the U.S., and digital cameras modified locally with housings and constructed from tig-welded aluminum alloy at my machine shop at home in Chiang Mai. The first cameras used Nikon L11 and L14 cameras and Snapshotsniper boards that were set-up in the forest of Kaeng Krachan National Park in Phetchaburi province in Southwest Thailand over a three-month period in October to December 2008.

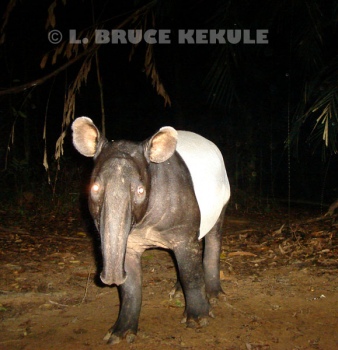

Asian tapir – mother and calf in Khlong Saeng WS, Southern Thailand

Animals captured were elephants, gaur, tiger, sambar and muntjac. One camera had over 300 captures in one month at a mineral deposit in the park.

Asian tapir calf in Khlong Saeng

Down in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary in the first part of 2009, I set both film and digital camera traps deep in the forest. Elephants, gaur, tapir, sambar, muntjac, golden cat and Argus pheasant were captured.

Tuskless bull elephant camera trapped at waterhole in Huai Kha Khaeng

I now have more than a dozen digital camera traps using primarily ‘Sony S600’ and W5-7 cameras, Snapshotsniper.com and Yeticam.com circuit boards.

Tusker elephant in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

The Sony cameras have been the best and most durable due to the manual features like ISO and f.stop adjustments. Picture quality with the ‘Carl Zeiss’ lens is usually good.

A herd of wild pigs including a runt in Khlong Saeng

Camera trapping has allowed me the sheer pleasure of seeing Thailand’s amazing wildlife on both film and digital. As of this writing, I have expanded my camera trap fleet to more than 20 units and continue to run a trap-line in Sai Yok National Park. On my first setting in July 2011, I got a mature Gaur bull up a hill in the interior. Still waiting on a tiger.

Big Cats in Kaeng Krachan: The tiger and leopard

A look at tiger and leopard evolution in Asia

At the beginning of the dry season in January, the jungle canopy is still mostly green but falling leaves begin to carpet the forest floor as the first cold snap arrives. Some species of trees start their transformation, producing a mosaic of yellows, oranges, reds, browns and greens. For the first few hours each morning, heavy fog blocks out the sun as moisture dissipates from the forest. The Phetchaburi River is crystal clear as it flows through this magnificent forest.

Indochinese tiger camera trapped by the Phetchaburi River

A large predator walks the trails seeking its next meal. Sensing danger, a muntjac barks a warning. The whole community of wild animals is on alert as macaques and langurs cry out from the trees above. A striped carnivore stalks a herd of wild pigs. The nervous omnivores squeal and panic, running through the underbrush to escape. But the big cat is lightning quick – it catches a young pig with sharp claws. The struggle is over in seconds as fangs penetrate to the spine.

Leopard camera-trapped on an old logging road

The tiger has just made a kill. It lifts the lifeless prey into deep cover and devours the carcass. After feeding, the big cat seeks water for a thirst quenching drink. It will then lie down and rest until the desire to eat or drink begins again. Tigers will sometimes move great distances in search of food. But where there is an abundance of prey species, these magnificent cats continue to live in balance with nature. The average kill ratio for a tiger is about twenty unsuccessful attempts for one actual kill. At a certain time of year, the male tiger will seek out a female to carry on his legacy.

Another tiger by the Phetchaburi River

Kaeng Krachan National Park is a great wilderness that sits in the Tenassarim Range in southwest Thailand. It is one of the most beautiful protected areas left in the country. Elephants, gaur, tiger, leopard, tapir, gibbons, hornbills and literally thousands of other plants and animals still survive in a rich ecosystem that is world class.

A tiger camera trapped at a mineral lick in Kaeng Krachan

To understand how the tiger and leopard evolved, we must go back to the beginning of these wild creatures. After the carnivorous dinosaurs died out about 65 million years ago, mammals with sharp teeth, strong jaws and claws replaced them as the top land predators. The first successful mammalian carnivores were the Creodonts that evolved during the Eocene epoch 57-35 million years ago. Creodonts ranged in size from smaller than a weasel to as big as a bear. A bear-dog also evolved during this period. These carnivores all had voracious appetites that were satisfied by large concentrations of prey species, mainly the odd-toed and even-toed ungulates that browsed and grazed the lush forests and plains of the time. The early Creodonts evolved into the modern carnivores that we know today: the bears, cats, dogs and other predators.

Tiger camera trap abstract

The order Carnivora is separated into three superfamilies: The Arctoidea includes marten, weasel, badger, otter, bear and the panda; the Cynoidea are made up of the dog, fox and the wolf; and the Herpestoidea includes the mongoose, civet, hyena and the cat. Most carnivores are dedicated meat-eaters, but some groups such as civet, panda and bear are omnivorous, eating meat and plants.

Leopard camera trapped on a nature trail in the park

Nimravidae were the first cats to evolve in the Early Oligocene epoch, about 35 million years ago. They lasted till the Late Miocene, some eight million years ago, when huge grasslands had developed around the world. The large saber-toothed cats were the first of the family Felidae. These long-fanged felines evolved alongside huge herds of grazing mammals like antelope and cattle. There were several different species of saber-tooth, but they all became extinct about two to three million years ago.

Black leopard camera trapped on the main road in the park

Modern cats belong to the family Felidae and include: tiger, lion, leopard, jaguar, cougar and cheetah, and all the smaller cats such as lynx, bobcat, jungle cat, fishing cat to name just a few plus domestic cats. Wild carnivores feed almost exclusively on vertebrate prey and sit at the top of the food chain. Tiger and lion have few predators apart from man but a pack of wild dogs however are a constant threat to the large cats and their offspring. The tiger and leopard belong to the genus Panthera, or roaring cats, that include the lion and the jaguar.

Leopard camera trapped in the interior

Thousands of years ago when primitive humans lived off the land as hunters and gatherers, they survived by pure instinct. They killed animals for meat and skins, and also gathered many different tools and plants from the forests. As humans became more sophisticated, they used weapons to take down larger animals. Clubs, spears, knives, bow and arrows were all that separated them from almost certain death at the claws and jaws of a predator many times their size.

Black leopard camera trapped on an old logging road

The possibility of being eaten by a carnivore like a tiger or leopard must have been on everyone’s mind that lived in or near the wilderness. Entering the forest where every step could be the last was like walking a tightrope. Attack normally lasted only seconds as a huge predator pounced from behind, biting the neck and causing almost instant death. Very few people survive such an incident. It must have been a scary environment to live in.

The will to survive, however, was strong and men eventually conquered his fear of the wild cats with more modern weaponry. The tables had finally turned and the predators became the hunted. As human populations and settlements grew, the forests were quickly transformed into agricultural land.

An Indochinese tiger on the prowl at night by the Phetchaburi River

After firearms were invented, European royalty, native kings, landlords, planters, foresters, government officials and many adventurers journeyed to the forests of Asia in search of the tiger. Mostly, they came to prove their dominance over the big cat. A trophy of tiger on the wall or floor at home proved beyond doubt that the owner was the supreme species. One could boast of their prowess as a hunter.

But the fact is most hunters shot tigers and leopards from the safety of a tree-blind, vehicle or elephant back. The cats would be attracted to within gun range by cattle, buffalo or a goat used as bait. For special hunts, hundreds of local villagers were recruited as beaters, trackers and mahouts. To join a shikar (Indian word for the hunt) was the ultimate experience for the adventurous.

The same tiger as above a few moments later

More tigers have been killed for sport in India then anywhere else in the world. In the days of the Raj, it was common to see five, ten or twenty cats lying dead on the ground in front of a hunting party. The Maharajah of Surguja killed some 1,157 tigers during his reign. Some Englishmen claimed to have shot more than 100 tigers. Fortunately in 1972, the Indian government finally banned hunting because the tiger and many other species were threatened with extinction.

The most famous hunter ever to overcome his fear of the big Asian cats was Jim Corbett of India. From 1907 to 1939, he single-handedly dispatched scores of man-eating tigers and leopards. His book ‘Man-eaters of Kumaon’ is a classic. Some cats mentioned in the book had killed hundreds of people. Corbett National Park was established in his honor, and the Indo-Chinese subspecies of tiger Panthera tigris corbetti is named after him.

In Thailand, the tiger and the leopard were also hunted for sport but on a much smaller scale than in India. In the past, rural Thai people living near wilderness areas built houses high off the ground that protected them during the night. But daytime was another thing. If they worked in fields bordering thick jungle or they went into the forest, they risked their lives.

At the turn of the 20th Century as modern firearms, agriculture and transportation took hold in the Kingdom, the forests and wildlife began to disappear. Man-eaters also declined. However, during World War II along the death railway in the Sai Yok district of Kanchanaburi province there were still accounts of man-eating cats. In recent times, there has been no such record. From time to time, domestic cattle are still killed by a tiger or leopard but this is now very rare. Low wildlife densities in the forest and easy prey are the main reason for this occurrence.

Thailand is fortunate in that tiger and leopard plus another seven species of cat still survive in some of the larger national parks and wildlife sanctuaries. Kaeng Krachan National Park is one of those protected areas that still harbor the big cats. Tigers can and do kill the leopard. Although their paths do cross, normally the spotted cat will avoid the striped predator. Documentary accounts and photographs do exist of tigers eating leopards.

In 2002-2003 while carrying out camera trap work in Kaeng Krachan in cooperation with the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department, I was surprised and elated to see both species tripping the same cameras in several areas only days apart. In one month, four different leopards, one of them black, were caught on film. In the following month, a leopard was caught during the day, and a huge male tiger stopped and posed for the camera. Both species were using the same trail for their hunting forays. A few other protected areas like Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai Naresuan wildlife sanctuaries have records of overlapping.

In Kaeng Krachan, an important discovery is that tiger and leopard hunt at all times during the day. It is usually thought they are only active in the late afternoon and throughout the night preferring to rest during the day. More research is required if we are to determine the pattern of daytime hunting by the big cats here. It is probably due to the pristine state of this forest and the lack of human activity.

Without doubt, the future of the big cats depends on one thing only – the complete protection of the remaining forests where they live. If the national parks and wildlife sanctuaries remain intact with a high number of prey species, the big cats will survive. But if overdevelopment and encroachment is allowed to continue, these magnificent animals will eventually disappear.

Unfortunately, too much time and money is wasted by too many organizations talking about saving the tiger and other wildlife, with very little actually being done. Human population growth will eventually destroy most wild places. Only true protection by a few dedicated people will slow the destruction of nature’s precious wildlife and wilderness areas. It is only hoped that the tiger and leopard will continue to survive as they have for millions of years.

Leopard – Panthera pardus

The leopard is closely related to the jaguar of South America. Both have a spotted coat pattern, incidence of melanism (black phase), and relatively short legs. The present distribution of the leopard is restricted to Asia Minor, India, Southeast Asia, the Himalayas, Tibet, China, Siberia, and Africa. Fossils of leopards were found in Pleistocene deposits throughout Europe, the Middle East, Java, and Africa, some 1.5 million years old. These secretive cats are mainly nocturnal. Their populations and ranges are difficult to determine but radio tracking of collared animals has shed new light on their movements and area they live in. ‘Spots’ is more tolerable to humans and their settlements.

Tiger – Panthera tigris

According to fossil evidence Panthera cats branched from the other Felidae about five million years ago in Asia. The first tigers originated in eastern China. Fossils of the earliest tigers date back to the Pleistocene epoch, about 1.6 to two million years ago, have been found in Henan, southeast China, and on the island of Java in Indonesia. The historic range of the tiger covered much of Asia and some of its islands.

However, humans have had an enormous impact on the geographic range of the species. The big cat only survives in 13 countries: Russia, China, India, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Burma, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. The present range is less than five percent of the tiger’s former range. There are less than 5,000 tigers left in the wild.

Goats in the Mist: Thailand’s Goat-Antelopes

Goral and Serow – Rare goat-antelopes

Photographing endangered species has become an obsession to me. Many of Thailand’s wild animals have come so close to extinction that their numbers are counted not in thousands or even hundreds but rather handfuls. Goral Naemorhedus goral are one such animal. Surviving on a few scattered mountaintops in northern Thailand, these even-toed ungulates are on the critically endangered list. With fewer than 60 individuals nationwide and low numbers at each site, the goral is considered one of the Kingdom’s rarest mammals.

Goral kid in early morning light at Keiw Mae Pan cliff – Doi Inthanon NP

Acquiring photographs of these goat-antelopes is a daunting task considering their natural habitat. Hunting pressure and encroachment have forced them to retreat to the steepest, most inaccessible limestone cliffs and forested mountains. Goral are still found in seven protected areas including Doi Inthanon and Mae Ping National Parks, and in the wildlife sanctuaries of Om Koi, Doi Luang Chiang Dao, Mae Tuan, Mae Lao-Mae Sae and Lum Nam Pai, all in the north of Thailand.

Another species of goat-antelope surviving in Thailand is the serow Capricornis sumatraenis. Both species belong to the Bovidae family, which includes cattle, sheep, goats and antelope. Bovids are ruminants with four-chambered stomachs. In some areas, goral and serow share the same habitat. They have short bodies with long legs ending in padded, gripping hooves enabling them to inhabit steep mountainsides and cliffs. They eat grasses, herbs and shrubs and gain moisture from the plants they eat. Their keen eyesight provides early warning of danger. Like all bovids, they do not shed their horns like deer do with antlers. Serow are normally solitary whereas goral are usually form small herds from four to twelve individuals.

Male serow caught by camera trap

Serow and goral are creatures of habit. These lofty creatures have favorite places to sun themselves, usually a rock or grassy mound. They can stand for hours on one rock as I witnessed in Doi Inthanon where a goral stood from about 9am to almost 12noon. Another habit is to defecate at the same place. Piles of pellets can be found wherever they live, usually on or around a large rock. Research on both species has now been undertaken by Mahidol and Kasetsart University staff studying the impact of human settlements near goat habitat and surveying the remaining populations.

Unfortunately, both species have been hunted for their meat, horns and oil which comes from boiling the head. Supposedly, the oil is used to relieve arthritis and bone ailments. The horns of goral and serow are black, corrugated at the base, pointed and swept back (like their relatives, the Rocky Mountain goat of North America). Their horns are not impressive but are still sought after by poachers. The tip of serow horn is used to make deadly spears which can be attached to a rooster’s spur during a cock fight. It is eagerly sought after, especially in southern Thailand.

Goral kid close-up

Hunting has decimated both goral and serow populations that numbered in the thousands as recently as 50 years ago. In many mountainous areas hill tribe people live and encroach on the forest for the purpose of slash-and-burn agriculture. This has played a major role in the disappearance of both species in the North. Lowland people also hunted them. In other areas where the serow are found, they have declined due to continued pressure from man.

Two sites were chosen to photograph these mountain creatures: Doi Inthanon National Park about 80 kilometers south of Chiang Mai and Mae Lao-Mae Sae Wildlife Sanctuary some 60 kilometers to the north. Staff at the protected areas confirmed goral and serow were still surviving. Working closely with the Wildlife Research Division in Bangkok. My plan was to set up photographic blinds as close to wild goat domain as possible and use a long telephoto lens. But this was easier said then done.

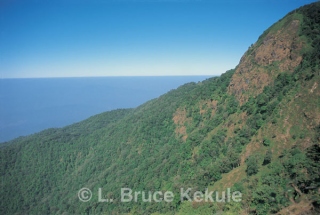

Keiw Mae Pan cliff in Doi Inthanon

Doi Inthanon, Thailand’s highest mountain, supports several small herds of goral around the summit. The animals are quite often seen close to Kew Mae Pan Nature Trail, developed in partnership with the Electric Generating Public Company Limited (EGCO) and the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department (DNP). Three kilometers from the road, a huge cliff rises some 2,500 meters above sea level and is criss-crossed with goat trails etched from thousands of years of use by goral and serow.

The skies are crystal clear over Doi Inthanon in November. This is truly a beautiful and remarkable place. But it does take some effort to get close to the cliff. The nature trail is strictly regulated and a local guide must be used for the three to four hour trek. If you are lucky and get up early, you may see goral and serow sunning themselves on rocky outcrops near the trail. Take a good pair of binoculars or telescope. This is also a good place for birdwatching, and you may see many species including the beautiful endemic green-tailed sunbird.

Doi Inthanon National Park

Mae Lao-Mae Sae is situated along the highway from Chiang Mai to Pai. A part of the sanctuary is divided by the road and Mon Liem, a giant granite massif, rises up to 1,200 meters above sea level. The sanctuary is home to a small herd of goral that survive on the summit. It is also criss-crossed by goat trails, and huge pine trees hundreds of years old are found here. The view is majestic, especially to the north where Doi Luang Chiang Dao Wildlife Sanctuary, another haven for goral, is situated. Wildlife sanctuaries are not open to the general public since they have been set aside for wildlife and biodiversity research. In October 2001, I glimpsed a male goral near the summit as the sun was going down. The goat unfortunately, was out of photographic range.

In November 2001, I visited the superintendent of Doi Inthanon to arrange a photographic trip after both goat species at the cliff. At 2,300 meters above sea level, temperatures can plunge at daybreak to zero degree Celsius with ice forming on the grass. It was tough getting out of the tent at 4 a.m. but it was important to move into the blind near the cliff face before the sun was up in order to photograph these wild goats. For the best photographic opportunities, the blind had to blend into the surrounding terrain so as not to spook the goats.

After four days of freezing, windy conditions, I spotted goral and serow on several occasions about a kilometer away. While scanning the cliff with my binoculars on the last morning, I detected a slight movement. A closer look revealed a male goral lying down on a buff about 500 meters from the blind. A short while later, he stood up. Using my 600mm Minolta lens with 2X tele-converter, I got some acceptable photographs of him.

This male had a fluffy white throat and underbelly. His gray winter coat was beautiful. After some time he did what goral do best – jumping straight down off the ledge in order to get closer to his mate who was feeding below. They butted heads affectionately a few times before disappearing into the maze of the cliff.

I made four trips to Doi Inthanon during the winter of 2001 and 2002 in search of goral and serow. Several herds of goral are still breeding here and can be seen almost every day. Serow are more elusive and only a few individuals were spotted from time to time. The spirits of the mountain listened to my prayers. On the last day of the fourth trip, a young goral about five months old appeared twenty meters away from me stamping its feet and snorting. It was nature at its best, making the front cover of this book.

Siriphum Waterfall in Doi Inthanon National Park

These wild goats have an uncertain future. Uncontrolled human population growth both inside and outside of the protected areas is bound to affect them in the long run. There is also the danger of disease carried by domesticated cattle and buffalo around the mountaintops decimating wild goats – something that needs to be checked and stopped at all costs.

Hunting of goral and serow continues in some areas, and the poachers are rarely brought to justice. Jail terms are too light and outdated. As a result, these animals need serious efforts to protect them from the dangers of the modern world with all the resources available, or they could vanish from the Kingdom’s mountaintops forever. A crime against nature should be on par with a crime against a fellow human being. Enforcement must be improved and implemented on a long term-basis. The Thai community needs more wildlife conservation education at all levels of society.

Serow – Capricornis sumatraenis

Serow share much the same predicament as goral but with a larger world range, they have fared slightly better and can be found in many mountainous areas in the Kingdom. In a few places they live all the way down to sea level. These goat-antelopes still survive in the Himalayas, northern India, southern China, mainland Southeast Asia and Sumatra. Several subspecies have been recorded and most populations are localized.

Serow have black or dark-gray coarse hair and a long shaggy mane down their backs. Two subspecies of serow are recognized in Thailand: those found in the steep limestone mountains of the south have black legs and those surviving in the Tenasserim range and further north to Burma have rufous colored legs below the knee. Breeding lasts from October to November and a single kid is born after seven months of gestation. Occasionally, twins are born.

Goral – Naemorhedus goral

Goral are found from about 1000 up to 4,000 meters. Their range is from the Himalayas and northern India, to southern China, Burma and northern Thailand. The Thai species are mainly gray-brown in color much like the boulders and rocks that they live around. A thin black stripe runs along their spine to a short tail. As with other wild Asian bovids like gaur and banteng, goral have white stockings from the knee to the hoof. With white patches on their throat and underbelly that stands out in bright sunlight, goral are distinct. They are compact mammals that can move up and down vertical cliffs with ease, and are tough to spot in their habitat. The breeding season lasts from November to December. One or two kids may be born in May or June.

Gurney’s Pitta – On the verge of extinction

The Gurney’s Pitta – Thailand’s rarest bird

Gurney’s Pitta in Khao Phra Bang Khram

The dark morning stillness of thick lowland rainforest of Khao Nor Chuchi, Krabi province, is broken by thumping footsteps as two humans move slowly down the trail. We carry heavy photographic equipment to a photo-blind set the previous evening, deep in the jungle. Precipitation is heavy as I set up in the hide. My helper departs quickly, conveying the message to the wildlife in the area that the intruders have left.

The ‘Emerald Pool in Khao Phra Bang Khram

Animals of the night fade into their homes and the ecosystem enters its daylight cycle. As morning light awakens the rainforest, sounds of dripping moisture begin to subside while forest birds and insects start their incessant calls as they have for millions of years.

Well hidden in the blind, I settle down, ever-vigilant for any movement on the forest floor. As the sun arches into the sky, light filters through the forest canopy in patches, illuminating the surroundings. There is a movement near the trail and a Hooded Pitta, common to this forest, hops about looking for food. The striking little blue-green bird with dark brown crown moves closer to the blind seemingly unconcerned about the looming structure.

Gurney’s pitta male

Snapping a few shots of the feathered creature but not wanting to alarm the other inhabitants of the forest, I continue to sit quietly hoping the spirits of the forest will answer my wish.

A morning rain shower passes by but quickly dissipates. As if on cue, a small black and yellow bird magically appears in front of the photo-blind, catching my eye. It’s the creature I’ve been waiting for: the Gurney’s Pitta!

Gurney’s pitta male

The little bird, perhaps sensing danger, quickly disappears into the darkness of the jungle but within minutes, is back again just long enough for only one shot with the camera.

The chance to see and photograph the Gurney’s Pitta, one of the rarest species in the world, has been my goal for several years. And this particular forest is the last known habitat for the bird which is both Thailand ‘s most endangered and a flagship species for the conservation of southern Thailand ‘s lowland rainforest.

Gurney’s pitta female

Gurney’s Pitta (Pitta gurneyi), or sometimes-called Black-breasted Pitta, is a small terrestrial forest bird endemic to Thailand and Burma . The male, with golden brown wings, bright yellow upper breast and flanks, black head and lower breast, white throat and brilliant iridescent blue crown and tail feathers, is striking indeed. The female is less colourful but, nevertheless, also very beautiful.

The species nests in spiny under-story palms laying three to four eggs but usually fledging at most two or three young. They hop about the forest floor and eat mainly insects and earthworms found amongst leaf litter but also take snails and little frogs.

Banded Pitta male

Extremely secretive, they keep as much jungle between themselves and any intruders. When danger approaches, they hop into the underbrush and disappear.

Of the world’s 31 known pittas, found from Africa to the Solomon Islands , and from Japan through Southeast Asia to New Guinea and Australia , 12 species are found in Thailand . They are Gurney’s, Giant, Banded, Hooded, Blue-winged, Blue, Blue-rumped, Eared, Mangrove, Garnet, Rusty-naped and Bar-bellied, of which the first five mentioned are found at Khao Nor Chuchi. The probable geographic origin of the Family Pittidae is in the Indo-Malayan region.

Banded Pitta female

Gurneys Pitta was first discovered in 1875 by W. Davison, a wildlife specimen collector working in Southern Burma for Allan Octavian Hume, a British civil servant working in India , and doyen of ornithology at that time. The bird was named after Humes friend, J.H. Gurney of the English county of Norfolk , and a fellow of the Zoological Society of London.

In the early 20th century, the bird was actually considered common in southern Thailand . Around the 1980s, it was thought to be extinct after no reported sightings had taken place for at least three decades. Then, in 1986, Philip Round, Thailand ‘s top birder, rediscovered the Gurney’s Pitta at Khao Nor Chuchi. It was big news for bird conservation groups and was heard around the world.

Historically, the world range of Gurney’s Pitta was a small concentrated area of lowland semi-evergreen forest along the coast and inland areas of the Thai peninsula, in the provinces of Trang, Krabi, Nakhon Si Thammarat, Surat Thani and Chumphon and Prachuap Khiri Khan. However, the once magnificent lowland tropical forest, its diversity of flora and fauna unsurpassed, has disappeared from most of those areas, due to man’s incessant greed, and his urge to destroy natural forest for the sake of agriculture and profit.

Khao Nor Chuchi, at Khao Pra-Bang Khram Wildlife Sanctuary, Khlong Thom district, Krabi, about 56 kilometres southeast of the provincial capital, is the last known site for Gurney’s Pitta in Thailand . Khao Pra-Bang Khram, with its headquarters at Ban Bang Tieo village, was established as a non-hunting area in 1987 by the Royal Forest Department (RFD), at the behest of Bangkok Bird Club (now Bird Conservation Society of Thailand-BCST), specifically in order to protect Gurney’s Pitta. It was upgraded to a wildlife sanctuary in 1993, with a total area of 183 square kilometres.

The Emerald Pool (Sa Morakot) within Khao Pra-Bang Khram Wildlife Sanctuary is a beauty spot visited by many local and foreign tourists. There are many trails open to nature explorers and bird watchers known as Thung Tieo Nature Trail Network. At least 318 different bird species have been recorded here.

The site’s alternative name, Khao Nor Chuchi, comes from the 650-metre-high conical mountain which overlooks the area. Bird photographers also come to Khao Nor Chuchi after images of the Gurney’s.

Many people, after travelling thousands of kilometres from different parts of the world, have left very disappointed after not seeing or photographing it. Gurney’s Pitta is a tough bird even to see, let alone photograph.

Although the species once occupied about 40 square kilometres of this area, most of the extreme lowlands where they live and breed were excluded from the sanctuary. As a result, forest is still being destroyed to grow rubber, oil palm and coffee, and human settlement has taken up most of the area.

Villagers still engage in poaching of animal and forest products from the reserved forest. On the day I photograph this Gurney’s Pitta, I still heard a gunshot.

Pitta numbers at Khao Nor Chuchi have declined drastically in the last two decades from an estimated 40 pairs in 1986, down to 21 pairs in 1992. This slide was due primarily to uncontrolled forest destruction, perhaps abetted by capture of the species for the black market trade in forest birds, and even for some government-run zoos.

According to BirdLife International’s Red Data there were only 11 breeding pairs and two extra males remaining in mid-2000. This year, only four to five nests have been found and sightings of individual birds have been minimal. At one nest that was abandoned, local birdwatchers found bird-nets put there by villagers who used the nets to capture the birds.

The species was also found along the coast and inland at the most southern tip of Burma but no reports of them have come from there since about 1914 and it is anybody’s guess whether it still survives. No surveys can be done due to inaccessibility of the area and danger of land mines. Tough government regulations have also kept most researchers away from the area.

BirdLife International, BirdLife Denmark , and NGOs such as BCST and the Oriental Bird Club have implemented a number of projects at Khao Nor Chuchi, in collaboration with RFDs Wildlife Conservation Division. However, these have slowed, but not halted, new settlements and further forest clearance.

Ultimately, unless the wildlife sanctuary can be expanded to encompass all remaining lowland forest, and previously cleared areas reforested, Gurney’s Pitta faces a very bleak outlook for survival. This magnificent bird could disappear before we know it and that would be a sad day for conservation in Thailand .

With just 11 breeding pairs left, the Gurney’s Pitta is very likely to be the first species to go extinct in this millennium, unless all parties concerned join hands in protecting it. On the day this male bird was photographed, a gunshot was heard.

Khlong Saeng: The Lost River

One of the Kingdom’s top wildlife sanctuaries still harboring many endangered but classic Asian animals

The weather is mostly clear as the sun drops behind a huge cloud close to the horizon. Light monsoon rains have begun at the end of April but hang in the mountains to the west. It has been a scorcher and heat from the day lingers over the reservoir. The light is soft and warm. About 6pm, a small herd of gaur drift out of the forest to drink at the waters’ edge and forage tender new grass. In a boat-blind about a kilometer away, I silently motor the craft closer using a battery operated trolling motor. The timing is perfect as I move in for a shot of Thailand’s magnificent but endangered wild ox.

Gaur cow in late afternoon light in Khlong Saeng

As I get closer, a mature cow feeding on an island in the lake sees something moving 100 meters offshore, and swims across to the mainland to investigate, all the time keeping her eyes locked on the strange anomaly moving in the water. Water drips from her underbelly, and her reddish-brown coat and deeply curved horns standout in the late-afternoon magic. I fire off a salvo of images hoping my camera and lens will capture this beautiful creature so late in the day. For a few brief moments, the old cow showcases Thailand’s natural heritage.

Young gaur bull

There are many beautiful forests in the South, but one in particular is truly a tribute to nature. Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary was once a magnificent natural watershed that provided water throughout the year to the inhabitants of the lowlands on the east side of the Thai Peninsula. It still harbors some very impressive animals such as elephant, gaur, tapir, serow, sambar, clouded leopard, sun bear, Great Argus (second largest of the pheasant family in Thailand), and the mighty king cobra – and the list goes on.

Gaur calf

Royal Decree encompassing 1,155 square kilometers of dense forest established Khlong Saeng in 1974. The sanctuary is the biggest in the Khlong Saeng – Khao Sok Forest Complex totaling more than 5,316 square kilometers and incorporating 12 protected areas, 11 of which are terrestrial and one with offshore islands in the Andaman Sea. Its forests are predominantly moist evergreen and most of the plants and animals are of Sundaic origin with some Indochinese species interspersed.

Curious gaur cow

Situated in the provinces of Surat Thani, Phang Nga, Ranong and Chumphon, the complex includes: Khlong Saeng, Khlong Yan, Khlong Naka, Khuan Mai Yai and Ton Pariwat wildlife sanctuaries, and Khao Sok, Kaeng Krung, Lam Son, Sri Phang Nga, Khao Lampi – Hat Thai Muang, Khao Lak – Lam Ru and Khlong Phanom national parks. They are under the responsibility of the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department (DNP) to provide protection, management and staff.

Gaur in the late afternoon

Khlong is the southern Thai word for a tributary or canal. The main tributaries of the Khlong Saeng valley include the Saeng, Ya, Yan, Ake, Mon, Ye and Mui that made-up the mighty Khlong Pasaeng. This river ran wild from the Phuket Range down to the Mae Tapi River in Surat Thani and eventually into the Gulf of Thailand. The riverine habitat teamed with flora and fauna, and the ecosystem was absolutely pristine. Tigers and leopards lived alongside many prey species like sambar, muntjac and wild pig. Elephants and gaur were fairly common. It was a magnificent wilderness at one time.

Gaur cow and her calves

But in the mid-1980s, a drastic change to the Pasaeng River was to come about. To increase Thailand’s electrical power needs, and back when building hydroelectric dams was in vogue, it was decided by the Electrical Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT), a state enterprise, and the government, to construct the Rajaprabha Dam that eventually inundated a total of 165 square kilometers (65 sq. miles) of the Khlong Saeng valley to become the Chiew Larn reservoir in 1986. The water body extends into the sanctuary for more than 50 kilometers (30 miles) but is only about two kilometers at its widest point.

Flooded forest in Khlong Saeng

Where rivers and forest previously existed, large waterways now provided easy boat access to virgin wilderness. The skeletal forms of what were once huge forest trees stand as a reminder of what disappeared beneath the flood more than a quarter of a century ago. Some trees still stand but many have come crashing down especially up-stream where decaying is severe. Millions of plants and animals perished as the floodwaters rose. The late Seub Nakhasathien, one of Thailand’s hero’s of wildlife conservation plus rangers and wildlife researchers saved hundreds of stranded fauna caught on islands. There are some 160 of them scattered throughout the reservoir when water levels are low. Some denizens were able to swim and move to higher ground but not all. It was the beginning of a new ecosystem – a large lake with a very long and complicated shoreline.

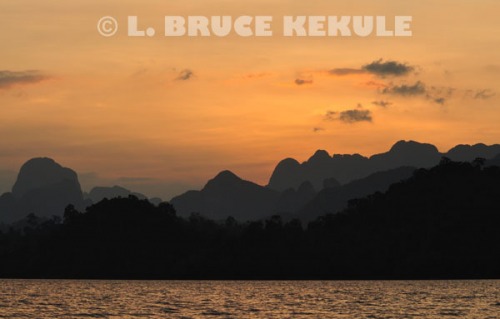

White-bellied sea eagle with a fish

Probably the most impressive scenic site in the sanctuary is the massive limestone ‘karst’ formations that were formed sometime during the mid to late Permian over 200 million years ago. It was a time of widespread mountain-building and volcanic activity. Thailand was part of Gondwanaland that was still attached to Pangaea, the ‘Supercontinent’. These colossal outcrops, some reaching as high as 960 meters (3,150 feet), look almost ‘architectural’ in design and are as impressive as the famous towers in Phang Nga Bay to the south. These configurations are the remnants of a prehistoric coral reef that once thrived here.

King cobra hunting for prey

Of all the animals in Khlong Saeng, gaur is probably the icon of wildlife in the sanctuary. These bovid are now rare in Thailand surviving only in a handful of protected areas, but they thrive fairly well. However, this only occurs around the upper reaches of Khlong Saeng and several other tributaries. The population of gaur here is estimated to be about 100 individuals and is one of the Kingdom’s best reserves for the species due to the dense moist evergreen forest.

Osprey in the mid-day heat

Breeding seems to be healthy; as many calves and young gaur of various ages have been seen in several herds I photographed at this site. Large solitary bulls keep the herd in stable breeding condition. These herbivores need huge tracts of forest free of human presence to survive. Being extremely shy, these wild cattle flee on the first sign of man. Good availability of food, water and minerals are important to their survival and the sanctuary provides these in abundance. There are still some elephants but their numbers seem to have declined. Further downstream, human activity has all but obliterated the large mammals including the tiger, which has not been seen for more than twenty years, even after extensive camera-trap surveys carried out by the research unit at the sanctuary headquarters.

Young Asian Tapir camera-trapped

Next door to Khlong Saeng is Khao Sok National Park covering 739 Square kilometers established in 1980. Khao Sok is well known around the world. The national park’s mandate in Thailand is to promote and encourage tourism into various nature sites within the protected area. After the Rajaprabha dam was completed, boats and wooden rafts were built at an alarming rate to accommodate this new business of boating visitors into the lake. Now there are hundreds of craft, many extremely noisy. Fishing was allowed and it was a free-for-all in the beginning with everyman for himself. All forms of fishing were used including explosives, electricity, nets, trap-lines and spear guns. Many areas were quickly depleted of fish, and fisherman must now venture deeper into the reservoir trying to eek out a living.

Old bull gaur camera-trapped

Actually, the Fisheries Department (FD) has a regulation in place that states ‘no fishing’ is allowed from the dam five kilometers to the limestone cliffs during the breeding season from 15th May to 15th September. This ban should extend completely into Khlong Saeng. Unfortunately, there seems to be little or any formal protection in place as boats and people come and go with no restrictions. Also, in Khao Sok, there are many rafts that have extensive facilities including a ‘karaoke’, which seems distant from nature. Every year the FD releases several species of fish into the reservoir. The ‘giant catfish’, a species found in the Mekong River, was released here and are most likely competing with other large resident fish. The FD has banned its capture but all fish are being caught for the pot, or sale to waiting ice vendors at the dock.

Dusky langur on a stump

However, a more serious problem exists that needs immediate attention before it is too late. When the Rajaprabha hydroelectric dam was finished and working on-line, EGAT passed a regulation and transferred protection duties to Khao Sok National Park. This included the complete waterway and 100 meters up into the terrestrial landscape meaning the entire water body intrudes deep into Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary for more than 50 kilometers and the mandate for its use and protection is controlled by the national park. People easily penetrate Khlong Saeng to poach, gather and fish, and the sanctuary officials have no authority on the waterway. Budgets are low and therefore, protection and enforcement is minimal. It is an extremely large loophole that needs to be fixed soon!

Gaur cow feeding on grass

EGAT, DNP and FD should join forces to find a viable solution, and take corrective steps to re-zone the reservoir. The solution is easy. About 20 kilometers into the lake at the mouth of Khlong Mon, the lake narrows down to about two hundred meters across. A rope barrier and guard post has been erected by the sanctuary but is unmanned for the most part due to the national park’s mandate. Constant overfishing and visitation to the upper reaches of Khlong Saeng over the long run will definitely have a serious impact on this sanctuary, especially gaur due to their very shy nature. Another very sensitive species is the Great Argus. These beautiful birds will abandon a breeding site if disturbed by humans. There are six hornbill and two gibbon species indicating a pristine forest. Stump-tailed macaque is the largest primate and dusky langur or leaf-monkeys are common. White-bellied sea eagle, lesser fish-eagle and osprey plus otters depend on fish and even though there is still some species in abundance, saturation fishing will eradicate most fish over time.

Sunset over the Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

The DNP’s mandate for ‘wildlife sanctuaries’ is straightforward; they have been set aside for wild species propagation, biodiversity research and habitat preservation. With hundreds and possibly thousands of people visiting Khlong Saeng every year, it is doubtful whether the sanctuary can sustain its habitat diversity over the long term. Also, trash and oil pollution from the boats is serious problem that needs attention and constant surveillance.

Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary is a beautiful but forbidding forest, and its incredible biodiversity it a tribute to the Kingdom’s natural heritage. In terms of research, very little is actually known about the interior but its future depends on many things. Most of all; the protected area should become the focus of attention so that all concerned may take a hard long look and save it for the future. Decisive and quick action in the only recourse before it is too late.

In the field:

After more than a decade of visiting forests in the East, West and North, I decided it was about time I went down South. From January 2009, I began a photographic and camera-trap program in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary. Over the course of five months, a trip every month was scheduled. On the very first outing, we arrived at our final destination after a four-hour boat ride. I jumped onto a floating raft (ranger station) not far from the headwaters of the Khlong Saeng. After a few minutes of unpacking and getting settled in, someone shouted out that an elephant was by the waters’ edge across from the ranger station in plain sight.

Young tusker elephant in Khlong Saeng

What a strange bit of luck. We immediately jumped back in the boat and crossed over to where a young tusker was feeding on bamboo leaves and occasionally taking a drink from the lake. He was alone and we could not figure out why. Possibly the herd bull or an old belligerent cow elephant had pushed him out. We will never know. This little bull was in good condition and looked fine. The next day, I was back at the same spot waiting but he did not show. The morning after, he was back. I left the next day but before we parted company, I decided to name him ‘Nong Saeng’ after the river. I thought that would be the last time I would see the little youngster.

Young bull gaur

A month later I was back at the station and the first thing I asked; where was ‘Nong Saeng? No one had seen him. Two days later about 4pm while I was traveling up-river in my boat-blind, I bumped into him again, but much farther into the reservoir. He was back by the shoreline feeding and I was elated to say the least. I stopped the boat and had a great time photographing this lively young elephant once again. He was seen a couple more times by the rangers but since then, ‘Nong Saeng’ has probably gone up into the hinterland as the monsoon rains have begun. This encounter will always create fond memories of nature’s little quirks and how things work out sometimes. Hopefully, I will get a chance to see him again next year in January when I return to continue documenting the wildlife at Khlong Saeng.

Khao Ang Rue Nai – Natural splendor in the East

Thailand’s largest remaining tract of lowland evergreen rainforest and a very important wildlife sanctuary

During mid-morning at a secluded murky stream deep in the Eastern evergreen rainforest, a single reptile glides effortlessly through the water to a favorite basking spot. Lying on the bank some three meters long, this freshwater Siamese crocodile warms-up in the bright sunlight. Judging from the many photographs taken of this individual, it is a mature animal. Sex and actual age are not known, but it has been here for sometime now. The habitat consists of several connecting deep ponds with abundant fish stocks. The crocodile takes occasionally small mammals and birds. It is a lucky but lonely survivor.

Sunrize in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

During mid-morning at a secluded murky stream deep in the Eastern evergreen rainforest, a single reptile glides effortlessly through the water to a favorite basking spot. Lying on the bank some three meters long, this freshwater Siamese crocodile warms-up in the bright sunlight. Judging from the many photographs taken of this individual, it is a mature animal. Sex and actual age are not known, but it has been here for sometime now. The habitat consists of several connecting deep ponds with abundant fish stocks. The crocodile takes occasionally small mammals and birds. It is a lucky but lonely survivor.

Little grebe in the reservoir

Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary is home to probably the last truly wild Siamese crocodile in eastern Thailand. There are just a few surviving in nearby Cambodia but their future is threatened by the construction of hydroelectric dams. Since Siamese crocs can live for 60-70 years, it is hoped this individual will be in Khao Ang Rue Nai for some time to come.

Bull elephant at a waterhole

Kitti Kreetiyutanont, a forest official working in the sanctuary, recorded the first sighting of this individual in 1987 by photograph. The croc still survives to this day, and is a tribute to the tenacity and longevity of the species. However, it is a case in point where humans are to blame for the disappearance of these remarkable creatures, from the lowlands all the way up into the forest; by encroachment, poaching and logging that went on for decades.

Bull elephant on the move

Some 230 million years ago judging from fossil evidence, the first crocodilians evolved from the Archosaur. Crocodiles have outlived the dinosaur but here in Thailand, the demise of the wild species is close at hand. In the past, crocodiles were found in just about every main river system throughout the Kingdom. Modernization has brought these mystical creatures to the brink of extinction. They were mainly captured to stock crocodile farms, and were also killed by the people who mostly feared the sometimes aggressive reptiles. With no laws in place at the time to protect these animals, extinction was imminent.

Banteng herd at a waterhole in Khao Ang Rue Nai

However, a very small reintroduction program could be implemented here, and with increased protection, could work to save the remarkable Siamese crocodile from extinction in the wild. There are several other sites that can also be used for reintroduction such as Yot Dom National Park in Ubol Ratchathani province, and Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary in Chaiyaphum province where crocs were once common. There are thousands upon thousands of crocodiles in farms, mostly by crossbreeding and hybridization. A wild population is the only option. A few of the crocodile farms still have

Banteng herd at a waterhole

Siamese crocodiles taken from the wild and could easily start a program to save the species. There has been one attempt at a national park to release crocodiles but it apparently was abandoned. Also, several Siamese crocodile have mysteriously showed up at Khao Yai and Thung Salang Luang national parks and believed to have been released clandestinely. These crocodiles should be captured and DNA checked to see if they are truly wild crocs.

Banteng cow with a lame right rear hoof

Khao Ang Rue Nai is situated in the provinces of Chanthaburi, Prachin Buri, Chachoengsao, Chon Buri and Rayong. The sanctuary headquarters is located about three hours drive from Bangkok and was established in 1977 by Royal Decree. The protected area consists mainly (80 percent) of dry-evergreen forest with moist and hill evergreen, dry dipterocarp and mixed-deciduous forests interspersed with many streams, and are eastern Thailand’s largest remaining tract of lowland evergreen rainforest in the country. An annual rainfall of some 3,000 to 4,000 millimeters (118-160 inches) has been recorded.

Mother elephant and infant

The sanctuary is 1030 sq. km (398 sq.miles) in area and is part of the Prachinburi floodplain. It is the largest protected area of the Eastern Forest Complex, which includes four national parks and three wildlife sanctuaries: included are Khao Chamao – Khao Wong, Khao Khitchakut, Namtok Phlio and Khlong Kaeo national parks, and Khao Soi Dao, Khlong Khrua Wai Chaloem Phrakiat and Khao Ang Rue Nai wildlife sanctuaries. Unfortunately, these protected areas are mere islands in a sea of humanity.

Burmese reticulated python

In the old days, the Eastern Forest Complex was known as the Phanom Sarakham forest, and was one of the richest forests in Thailand famed for its abundant flora and fauna covering an area of about 8,000 square kilometers. Just a short 50 years ago, this dense, lush and vast jungle was home to large herds of elephant, gaur and banteng. Tigers and Asian wild dogs were common as were most of the smaller mammals like sambar, serow, wild pig, and muntjac (barking deer). Hornbills and gibbons, indicator species of an intact forest, thrived. But that quickly shrank as the human population expanded in causing irreversible damage to the ecosystems.

Variable squirrel

Due to its close proximity to Bangkok and other cities, many city hunters entered this forest at night spotlighting, either on foot or by jeep. This decimated the wildlife as everything was taken without regard for species, sex or age. The most damaging was the eight 30-year logging concessions carried out by logging companies that cut many roads into the forest. This alone-allowed easy access to virgin forest and it was not long before most everything vanished. In the meantime, this wilderness was also completely surrounded by agricultural land, which also took its toll.

Crab-eating macaque eating ‘mama’ dried noodles found in a trash can

Fortunately, and before it was too late; enough forest was saved so that the mammals and others were able to survive to the present. Although populations of the large herbivores have declined, they can be still be seen at various sites within the sanctuary. Unfortunately, the tiger has disappeared but a few Asian wild dogs still roam the interior and are at the top of the food chain.

Lessor whistling ducks

In 1967 when the Vietnam War was in full swing, the government cut many new roads through the forests in eastern Thailand supposedly to facilitate movement of US personnel and equipment from Utapao Airbase to other airfields in the Northeast. At the end of the Cambodian civil war in 1986, the Thai Army made one such road through the top half of Khao Ang Rue Nai. The impact of the road on this forest and the animals has been devastating and many creatures have been killed or maimed by vehicles on this thoroughfare.

Lessor whistling ducks

The research unit stationed at Khao Ang Rue Nai on road-kill, deer and bovid population, elephant management and jungle fowl has carried out much research. Most accidents happened from 6pm to 6am. After much publicity, the road is now closed from 9pm to 5pm everyday and road-kill has dropped 70-80 percent. This is a plus for conservation where like-minded people have taken action to help prevent further carnage of wild animals.

Lessor whistling ducks

A total of 132 mammal, 395 bird, 32 amphibian and 107 reptile species have been recorded. Thousands of plant and insect species are found. Birds such as the black-and-red broadbill and the Siamese Fireback thrive. The rare woolly-necked stork and lesser adjutant once lived in these forests but have not been seen for sometime and are presumed extinct locally.

Oriental darter

Rare water birds like the Oriental dater and great cormorant migrate here and stay for several months at a reservoir built near the headquarters. This water source was created for the elephants during the dry season hoping to help eliminate human-elephant conflict. The marauding giants in search of food and water have killed and hurt many people. There are also recent reports of foraging gaur attacking farmers outside the sanctuary by mostly young bulls kicked out of the herd.

Oriental darter

The dangers facing Khao Ang Rue Nai are now severe as poachers and farmers snare indiscriminately. Cheap and simple rope snares have killed many elephants, gaur and banteng plus many other mammals. The villagers say they are protecting their crops. But many areas are in close proximity to the forest and interaction between wild beast and humans is a serious problem for the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department, who are constantly under pressure from these conflicts. More personnel and protective management plus a bigger budget are needed to protect these forests.

Great cormorant and little cormorant

Great cormorant

Little cormorant

But it must also be understood by the general public that wildlife sanctuaries are not open to the general public and have been set aside for species conservation, protection and bio-diversity research. Unlike national parks, recreation is not encouraged although it does occur, especially at waterfalls and viewpoints. Needless to say, the future of all conservation areas in the Kingdom is in the balance, and only increased protection, conservation awareness and education are the keys to sustain Thailand’s wonderful natural heritage.

Notes from the field:

For capturing images of such elusive creatures like crocodiles and elephants, infrared camera-traps are a very productive alternative to endless days of sitting in a hot photo-blind. Crocodiles are creatures of habit, so I set a camera-trap at its favorite basking spot by Klong Takrow. The croc was caught on film many times during a two-week session. One frame shown above was taken in early morning light. It seems as if the crocodile is smiling, and saying, “I’m right here”. I was elated to get such a lucky shot.

Siamese crocodile camera-trapped at Klong Takrow

Khao Ang Rue Nai is currently home to about 130 wild elephants. The road transects the northern part straight through old elephant habitat. The narrow road was widened and resurfaced allowing faster speed. In 2002, a man and woman in a pickup truck barreling through the sanctuary at high speed did not see the elephants on the road until it was too late. The truck crashed head-on into a 5-year-old tusker. The truck’s driver was killed on impact but the woman survived. The young elephant died shortly after.

The ironic circumstances of this accident – ancient animal and modern machine – weighed heavy in my heart. I had set camera-traps near the crocodile pond in the sanctuary a couple of weeks before. When the film was retrieved and processed, I was elated that a herd of elephants had triggered one of the cameras producing several frames. One frame showed an inquisitive little tusker looking straight at the camera. My elation quickly subsided a few days after the terrible news on TV and newspaper reports that a small tusker had been killed in the sanctuary. My worst fears were confirmed after consultation with Royal Forest Department officials and comparing photographs. A scar on the dead calf’s forehead proved it to be the same animal that I had ‘camera-trapped’.

Such accidents are a terrible blow to the conservation of Thai elephants, because tuskers are particularly vulnerable, being subject to hunting for their ivory. This young tusker was not the first and probably not the last elephant killed by reckless driving on this road. However, the Royal Thai Army and the Department of National Parks should be commended for taking the initiative by partially closing the road at night.

It is hoped that one day the time will be extended from 6pm to 6am to increase the animal’s chances for survival. This is the logical step and humans using this road would have to adjust to the new times for the sake of saving the wildlife.

Kaeng Krachan: Jewel in the Tenasserim Range

One of the Kingdom’s Last Great Tiger Reserves: Thailand’s Largest National Park and Biodiversity Hotspot

Just a short forty years ago, a local Karen hunter sitting alone in a tree-stand made of bamboo waits by the headwaters of the Phetchaburi River. He has trekked south from his humble abode for about a week. This young man is a traditional hunter and knows how to subsist by himself in this forbidding forest. His father before him also hunted this place and taught him all the tricks-of-the-trade: hunting for a living and surviving in the wild.

Rainbow over the Phetchaburi River

Darkness envelopes the man as the sun sets behind him. The moon and stars are brilliant and night visibility is good. The location is a mineral deposit (salt lick) deep in the interior close to the river. This site attracts gaur, banteng, elephant, and the extremely rare Sumatran rhino, plus sambar, muntjac and wild pigs. Tigers and leopards also came looking for prey. It was a magnificent animal kingdom.

Serow camera trapped on old logging road

His primary target was the rhino but would take anything that came to the natural seep for the life-giving minerals. The hunter sets in for the night knowing the large mammals sometimes prefer to visit in darkness. He is armed with a crude self-made muzzle-loading rifle. It is the dry season, and he is not too worried about a misfire. The caliber is as large as his thumb, and the round heavy lead ball and black powder charge is enough to take down an elephant.

A great hornbill lifting off a fruit tree

At last, a dark shape emerges from the forest and slowly ambles straight to the seep. Head down, the odd-toed ungulate drinks to quench its thirst. The hunter switches on his flashlight and temporarily blinds the two-horned rhinoceros. He takes aim and fires his weapon with a resounding boom and tremendous muzzle flash that breaks the still night. The creature is hit in the shoulder and runs for a short distance before collapsing. It is a long wait but dawn eventually comes and the hunter climbs down from the platform to investigate his trophy. Sadly, he just killed one of the last few Sumatran rhinos left in this forest.

Indochinese tiger caught by camera trap by the Phetchaburi River

Shortly hereafter, he dispatched another rhino and then never saw the species again. He sold the horns, which were small, for about 100 U.S. dollars to a waiting middleman: a pathetic return compared to what the horns probably fetched on the black market which was most likely in the thousands of dollars. This voracious wildlife trade has absolutely wiped out many species from the forests throughout the Kingdom. It has been devastating and unfortunately, still carries on to this day.

Indochinese tiger camera trapped at a mineral lick

When Kaeng Krachan was declared a national park in 1981, the hunter, his family and several other families in the little village were relocated more than twenty kilometers outside the boundaries of the protected area. A plot of land was given to them but it was not to much, probably just sustainable. He was told that he could not hunt anymore and had to eke out a living by farming. It was a difficult road ahead for them after living in the forests since they were born. Relocation was tough but they adapted and survived. The hunter and his family now plant pineapples and other crops. He stopped hunting, and his two sons actually care about conserving the forest and wildlife.

Bull elephant camera trapped at a mineral deposit

The Phetchaburi is one of Thailand’s most famous waterways. King Rama V visited this waterway and His Majesty had water sent to his palace in Bangkok for drinking purposes. The King was also presented with rare white elephants found here. During his reign, both Sumatran and Javan rhinos existed in the interior in good numbers.

Tiger camera trapped by the Phetchaburi River

In 1914-1915, an Englishman named K.G. Gairdner made many forays into the Phetchaburi watershed recording the wildlife. He published several papers in the Natural History Society of Siam about his exploits and encounters in this wilderness. Large herds of elephants and gaur were present and many tigers thrived due to the prolific amount of prey species.

Tiger camera trapped by the Phetchaburi River

The Phetchaburi River flows from the Tenasserim Range through Kaeng Krachan, the Kingdom’s largest national park encompassing 2,915 square kilometers (1,125 square miles). It is still pristine within some areas of the park. Montane forest is found on the highest peaks with predominantly dry evergreen forest interspersed with mixed deciduous vegetation. Even though both species of rhino have disappeared, the park continues to showcase a great diversity of wildlife.

Gaur camera trapped at a mineral lick

Rare and endangered animals still survive such as the Siamese crocodile and stumped-tailed macaque as well as elephant, gaur, tiger, leopard, Asian wild dog, tapir, sun bear and Asiatic black bear. Other mammals such as sambar, and the rare Fea’s muntjac plus common muntjac and wild pig keep the balance of nature intact by providing ample prey for the carnivores. Banteng were common in the mixed deciduous lowlands but humans encroaching on the forest soon eliminated most of these wild cattle and there are very few remaining if any at all.

Gaur herd spooked by camera trap

However, the Phetchaburi is still an important watershed and is the main source of water for people on the lowlands. Hornbills and gibbons are plentiful. I once listened to four separate gibbon groups calling at the same time from Phanern Thung Mountain. The surrounding forest contains fertile food in abundance and safe habitats for all the wild animals. Both Sundaic and Indo-Chinese species survive here.

Gaur cow camera trapped at a mineral deposit

The Phetchaburi is one of the Kingdom’s least disturbed waterways and although the lower section is dammed, the upper reaches of the river are still fairly intact. More than 400 bird species have been recorded in Kaeng Krachan and thousands of unusual plant and insect species can be found. There are more than 70 species of fish in the waterway. Many reptiles including the king cobra and reticulated python, and amphibians like the giant tree frog are here. There are probably some species new to science still to be discovered, specially insects and plants.