Sign Up or Log In

Gallery

Recent posts

- THAILAND’S NATURAL HERITAGE: A look at some of the rarest animals in the Kingdom – Part One

- WILDLIFE in THAILAND: A Photographic Portfolio of Thailand’s Natural Heritage – Part Three

- WILDLIFE in THAILAND: A Photographic Portfolio of Thailand’s Natural Heritage – Part Two

- WILDLIFE in THAILAND: A Photographic Portfolio of Thailand’s Natural Heritage – Part One

Archives

- May 2020

- April 2020

- November 2019

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- August 2017

- July 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- January 2017

- November 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- July 2009

Links

Wildlife Links

Posts Tagged ‘muntjac’

First time DSLR Camera Trap Location

‘Tiger, leopard, tapir, gaur, elephant, sambar and barking deer visit a Nikon D90 camera trap…!

A female Indochinese tiger camera trapped near a ‘hot spring’ in the ‘Western Forest Complex’ of Thailand…(image cropped)…!

For some twenty years, I have been visiting a natural seep in the Western Forest Complex of Thailand to photograph wildlife that come for important minerals flowing from a rocky formation. It has been extremely rewarding over the years, and I finally decided to set a DSLR camera trap just above the natural hot springs.

In one frame, this female stepped forward and turned its head because of the flash…!

I knew that tiger and leopard visited this place hunting prey species like muntjac (barking deer), sambar, wild pig and tapir plus other animals such as gaur, banteng and elephant. I chose a trail that is about 4 meters away from the hot spring. I left the cam for almost two months and it was still working when I returned, but flash power had long drained away.

Same female tiger back again 2-weeks later at night…!

A female tiger visited first at night on Feb. 14, 2017. She then came back past the cam three times on Feb. 21, again at night passing the camera several times. Then a leopard came by during the daytime on Feb 26th. Other creatures like sambar, muntjac, tapir, gaur and elephant tripped the camera many times during the two-month soak.

The female once again that night…need to move the cam for future head-on shots…!

And again making for a very good record of her visit to this cam…!

However, most shots are all butt shots. It looks like they have come to the spring and then walked past my camera going up-hill hence mostly rear-end shots.

A male leopard walking past in the morning. Daytime shots of carnivores are rare here…!

I hope to go back here in a week or so where I will be moving the camera with a wide-angle lens for more on-coming shots.

A female tapir in mid-afternoon passing the cam.

Tapir pair with the male on the left…

I’m also after a black leopard that I have seen here almost twenty years ago and then again recently about two years ago.

A young female gaur on the way down to the hot-spring…!

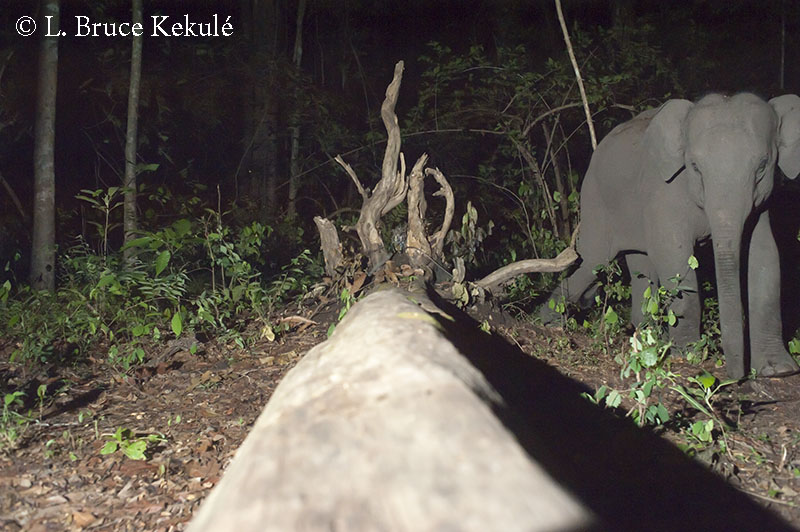

Elephant trunk, tail and legs…! These giants always test my ‘elephant proof’ cameras…!

A scruffy sambar yearling at night…!

I was delighted to get this amount of wildlife traffic and look forward to future set-ups’ here…!

Tiger Hunter testing his Nikon D90 DSLR camera trap…!

PLEASE NOTE: Recently, an American so-called ‘Wildlife NGO’ stole one of my tiger images, cut my name and copyright off the image and published it on their website without any permission to use said image and credit to me. At this time, I’m not sure what course of action I should take. However because of this, I will now be ‘water marking’ through the subject on all of my images for the future with my name as follows: © L. Bruce Kekulé

I thought that an American NGO would be honest and sincere about © copyright…but that is not the case as proof of theft has been recorded and action is being taken against this NGO and its CEO.

Camera trap blues plus a close encounter…!

Two stolen cams and a female elephant in the dense bush on Dec. 30, 2016…!!

An Indochinese tiger passes my Nikon D700 DSLR camera trap on 8/13/2016 – 6:24 AM…!

As most of my friends know, I went to the USA back in September 2016 to do a road trip and my first ‘bucket list’ visiting the Grand Canyon, Zion, Grand Teton and Yellowstone national parks respectively, and then up into Canada. It was a great trip and I was able to tick those items off my list. I returned to Thailand on Nov. 15th and it took me sometime before I could get into the forest to check my camera traps.

A young bull elephant taking in minerals…!

Before I left, I set four DSLR traps, and three video cams where I usually work in the ‘Western Forest Complex’ northwest of Bangkok. Over the years, this place has proven very productive capturing photos of tigers and other cryptic creatures in the wild forests found here. Thailand’s natural legacy is still thriving and I have some remarkable images of nature on file.

A banteng bull bolts as the cam’s flashes go off…!

Unfortunately, lady luck decided to look the other way. Two videos (a Bushnell Trophy Cam and a ‘Fireman Jim’ DXG 125-day only cam) were stolen by poachers (or some other dishonest and very undesirable people) which of course was a shock to me…I’ve been working in this sanctuary for more than 20 years and never lost anything…I was proud of this fact and record. So it’s back to the drawing board to improve the possibility of theft. I have ‘elephant proofing’ down pat but a new design to double-up the security of all my cams is needed (extra work for me) and I will post this at a later date.

A pair of banteng cows bolt from the mineral deposit…!

So I decided to move out of the area and not set any camera traps here for now. But there is a hot-spring close by with a blind set up to facilitate photography through the lens. This natural place has tiger and leopard that roam around and it is here 18 years ago, that I photographed a black leopard up at the mineral deposit. I got my Nikon D4s with a 200-400mm lens and tripod, and a Nikon D3000 with a Tamron 70-200mm lens ready plus some snacks, water, camo material plus my pistol (remember elephant country) and hiked in about a kilometer to the blind. On the way in, I bumped into a wild elephant camp with fresh tracks and poop all over the place. A big herd was nearby…!

A young sambar stag in the morning…!

As usual, I just moved through and then sat in the blind that afternoon collecting some nice shots of barking deer and a young male peafowl shown here. Around 6pm, I packed-up for the walk back to the truck. About 100 meters down the track, I saw a big elephant on the trail…oh poop, my trail back to the truck was blocked and I certainly was not going to put my life in jeopardy (mother’s with small baby elephants or big tusk-less bulls means certain death). I turned back towards the blind and there was another smaller jumbo behind me.

A pair of sambar does late at night…!

This was serious as it seemed I was surrounded by the herd. So the only thing was to pop-off a round in the air with my Colt Government .38 Super Auto which brought out a roar from the big one down on the trail but the little one fled into the bush. I rushed back to the blind and threw down my chair and some trash in a plastic bag, and then hauled butt up another hill with a trail back to my parked truck. Up I went and it was rough going but I continued on. After about 20 minutes of thrashing around, it turned dark. With my headlamp on, I still struggled to find a trail. I got the shock of my life when I bumped into a huge female elephant not more than 6 meters away. She snorted at me and made a short mock charge but some small trees and saplings stopped her short. My pistol was out again and I let off another round in the air, and then yelled for her to Go, Go, Go as loud as I could.

A very old tapir taking in minerals…!

I was lucky as she was alone, and squealed high-tailing it in the opposite direction. I let out a sigh of relief and took stock…I had my iPhone and turned on the compass and went west. I then found a worn path back to a mineral deposit at the front near the road and eventually my truck. Now that was a close call and one that I do not want to repeat.

Muntjac (barking deer) pair at the hot-springs in mid-afternoon…!

It was about 8pm before I got going. About 10 kilometers down the track back to camp, I took a wrong turn and ran over a huge bolder getting stuck. Had to winch myself over it (just replaced a broken cable a few days before – lucky). I got back to camp arriving about 9pm. At the station, had a few sundowners to calm my nerves and then it was straight to bed. I had to go back to the blind the next morning to pick-up my camp chair and that rubbish I had left behind the night before. As I went through the mineral deposit, the elephants had retreated to the deep bush and I passed through without incident..!

A female muntjac jumping in front of a young male peafowl in display…!

I then left the area and went to where I had set the four DSLRs. During the time I was in the States, my D700 performed extremely well. Got a tiger a few days after I set the cam in late Aug. 2016. Also, got banteng (wild cattle), elephant and sambar and barking deer plus an old tapir. The other three cams did not work at all and I got nothing (primarily battery problems). One of the D700’s flashes and the sensor got ripped up by elephants as I did not have a sturdy tree to attached them to and just laid them on the ground (big mistake). The other flash and the D700 were fine having attached with lag bolts to a tree. I will be setting this D700 nearby at another deposit with a bigger tree…!!

All that’s left of a Bushnell Trophy Cam…!

All in all, getting the tiger was a plus even though it’s not a very nice photograph with leaf shadow on its face from the flash on the ground. As soon as time permits, I’ll be setting more DSLRs at my favorite places before a scheduled trip to India in late-February…! Finally, I want everyone to know that I carry a pistol for protection, and as a noise-maker when necessary as in this case. I might not have made it back on the 30th December if I did not have my sidearm…!!

All that’s what is left of a ‘Fireman Jim’ DXG 125 video cam: Opened by humans and then bent by elephants…!

Following is a gallery of elephants by camera trap and through the lens…!!

This is what they call a ‘Tuskless Bull’…taller and bigger than a tusker…!

A family unit has just left the hot-spring close to where I was sitting….they were about 100-yards away…!

Bumping into one of these guys or gals at night can be scary…!

And they can ring your neck and that’s be all she wrote…!

A youngish elephant at the old ‘tiger log’…!

Elephants camera trapped by the river…!

A young tusker and female on a trail in the bush at night…!

Even a very young bull could wreck havoc if you bumped into him deep in the bush…!

The ‘tiger hunter’ setting one of his cams in the ‘Western Forest Complex’…!

For the most part, wild elephants will flee at the first sight or smell of humans. However, there are exceptions and many a trekker, poacher and ranger has met their fate with a mother and infant, or an old mean bull. The best option is to climb a tree but this is not always possible. Running uphill is another way to escape these beasts if they are determined to stomp you…I always pray to the forest spirits not to bump into the jumbos period….life is too short…!!

A goral and a muntjac on the D3000 in India

Two even-toed ungulates caught by my DSLR travel cam…!

Another two species captured on my Nikon D3000 travel cam was a goral (goat-antelope) and a muntjac male (barking deer). Even though these two even-toed ungulates are not as glamorous as the tiger, they are still an indication of the prey base found in Vanghat Wildlife Reserve (private land) in the Corbett Landscape. Hopefully sometime next year, I will be able to return to this place but earlier (about Feb.when it’s cooler). It was boiling hot this year and a bit of a fire hazard (many areas are now being razed by fire) and certainly if I had waited any longer, my camera may have been burnt to crisp)…!

Goral (goat-antelopes) are found in Northern India in the foothills of the Himalayan Mountains…!

A muntjac male (barking deer) are found all over India and a main food source for the big cats…!

Sony P41 catches tiger and black leopard

Last month I posted some photos collected from my BFOutdoors P41 trail cam and decided to leave it for one more set. The following pics are what the great little trail cam has captured. Of note: I got four captures of a black leopard which is simply amazing….plus I two Indochinese tigers…I have moved this cam to another location further up the road and have installed my Canon 600D on the tree across from the daytime black leopard shot so that could also be interesting when I visit in a few days…two deer species and a banteng also crossed in front of the P41…Enjoy..!

A black leopard in the afternoon: A Canon 600D is setup on the tree opposite the leopard…!

A female tiger at night.

A male tiger in late afternoon.

Another black leopard capture.

Back again.

A male muntjac (barking deer).

Male muntjac again.

A banteng crossing in the daytime.

A young sambar stag in velvet.

Revisit: Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

Some old camera trap shots of wildlife in Southern Thailand

Limestone ‘karst’ mountains at sunset in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary.

In 2009, I decided to go down south to a wildlife sanctuary that was still teaming with animals common to the wet tropical forests found here. Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Surat Thani province is some 500 miles from Bangkok and is one of the top protected areas in the country.

Flooded forest near the headwaters deep in Khlong Saeng.

Once upon a time, this forest was a magnificent natural watershed that provided water throughout the year to the inhabitants of the lowlands on the eastern side of the Thai peninsula.

Clouded leopard at the entrance to a limestone cave probably searching for dead bats.

It still harbors some very impressive animals such as elephant, gaur, tapir, serow, sambar, clouded leopard, sun bear, Great Argus (second largest of the pheasant family in Thailand), and the mighty king cobra to name just a few – and the list goes on.

A serow (goat-antelope) at the same cave.

Probably the most impressive scenic site in the sanctuary are the massive limestone ‘karst’ formations that were formed sometime during the mid to late Permian over 200 million years ago. Thailand was part of Gondwanaland that was still attached to Pangaea, the ‘Supercontinent’.

A serow at another location at the top of a limestone ‘karst’ mountain.

These colossal outcrops, some reaching as high as 960 meters (3,150 feet), look almost ‘architectural’ in design. These configurations were thrust up when India crashed into the Asian plate some 60 million years ago, and are the remnants of a prehistoric coral reef that once thrived here.

An old tapir up near a cave at the top of a limestone massif.

But in the mid-1980s, a drastic change to the Pasaeng River was to come about. To increase Thailand’s electrical power needs, and back when building hydroelectric dams was in vogue, it was decided by the Electrical Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT), a state enterprise, and the government, to construct the Rajaprabha Dam that eventually inundated a total of 165 square kilometers (65 sq. miles) of the Khlong Saeng valley to become the Chiew Larn reservoir in 1986.

A tapir calf with its mother in the forest near the headwaters.

The water body extends into the sanctuary for more than 50 kilometers (30 miles) but is only about two kilometers at its widest point. As the reservoir filled up, thousands and thousands of trees and animals perished in the rising waters. It was destruction of a natural habitat in the name of modernization.

A tapir with clipped ears; probably nipped by a mature female chasing the young one out.

Awhile back, my friend Greg McCann, founder of ‘Habitat ID,’ a NGO setup to investigate forests in Southeast Asia contacted me. He was interested in starting a camera trap program somewhere in Thailand and Khlong Saeng was chosen as the first forest to see what is still thriving there.

A gaur calf on the trail up on a limestone mountain.

We have just returned from the sanctuary where eight cameras including one DSLR (Nikon D90), a Sony W55 ‘home brew’ and six Bushnell Trophy Cams were set-up in some of the areas where I previously captured some amazing animals.

A very old bull gaur with its hooves in poor condition…!

We will let these cams soak for two-three months and I will be going back then to see what has transpired. It should be interesting…!

A couple of young gaur in the mountainous forest.

When I first began visiting the area, I took my boat-blind (kayak with pontoons and electric trolling motor as a stable shooting platform) to navigate the waters and shoreline.

Another young gaur on a trail up in the limestone mountains.

Over the course of two years, I was able to get some really neat images of the wildlife that had adapted to the new environment. I also began a camera trap program to see what cryptic animals were thriving up in the evergreen forest.

A mature sambar stag on a trail in the forest.

A mature male muntjac (barking deer) on a wildlife trail.

A female muntjac with white spots along the spine and rear torso: a strange anomaly…!

A stump-tail macaque (monkey) up in the limestone crags with its jowls full of food.

An Argus pheasant at the mouth of a cave.

This gallery of shots is just some of the creatures collected over a two-year period (2009-2010). Some of these images are not the greatest but do show the biodiversity of this amazing place. I plan on setting up several DSLRs at these old camera trap locations and will post any new images down the road. Enjoy…!

Wild Thailand Part One and Two

For the first time, a snarling tiger shows what their reaction is to a video cam with red LEDs when actuated at night. This male tiger is a resident at this location in the ‘Western Forest Complex’…a black leopard also passed the cam several times but did not actually look at the LEDs and so no reaction was recorded.

At the second location, the tigers did not seem too bothered by the red blob…! I now have a few cams including my Nikon D700 set-up here and hopefully will catch a tiger with my DSLR trail cam…!! Please enjoy these videos and even though they are a bit fuzzy, still show Thailand’s amazing natural heritage at its best.

Muntjac: Thailand’s Barking Deer

Small cervidae and even-toed ungulate

Persecuted for the pot, muntjac still thrive in many protected areas around the Kingdom

Male muntjac in Khao Yai National Park

As the sun starts its daily ascent from the eastern horizon, the early morning air is crisp and cool. It is November and not a single cloud is seen in the clear blue sky. Heavy dew blankets everything in Mae Lao-Mae Sae, a wildlife sanctuary situated in the northern province of Chiang Mai northwest of the capital. Mist rises from the forest as the morning heat builds. Scent from pine trees, some hundreds of years old, is refreshing. A ‘sea of fog’ covers the lowland valleys and the view from the mountaintop is breathtaking.

Birds begin their incessant chirping, and a single gibbon calls from the interior. Butterflies cling to tree branches waiting for their wings to dry out, and other creatures of nature begin daily rituals. Life in this northern wilderness is pure as it has been for millions of years.

Fea’s muntjac male camera trapped in Kaeng Krachan

A huge granite massif sits in the sanctuary a couple kilometers from the main road. A pack of Asian wild dogs are zigzagging through the forest searching every nook and cranny for prey near the peak. They bump into a local resident muntjac male munching on fallen fruit.

The mature buck hears the dogs yelping and is instantly on high alert. Sounding much like a domestic dog, this small-sized deer emits a loud bark continuously until the threat is gone. The warning call is heard over many kilometers distance alerting all the other animals within audible range that a predator is on the prowl. This extremely fast cervid is now on the run weaving and darting through the forest. It escapes the slower dogs to live another day, and the pack carries on with the hunt.

Female muntjac on the run in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary

In another scenario, a lone leopard hunting for quarry gives chase to a female muntjac in Huai Kha Khaeng. The doe becomes confused and makes a wrong turn. In seconds, the big cat pulls the creature to the ground and goes in for the kill. But it is just another day in the balance of nature where the struggle for life and death between predator and prey is played out.

Muntjac, also known as “barking deer”, is a small deer of the genus Muntiacus with short antlers on the male joined on a very long pedicel or bony base. Females have no antlers. Both sexes have long canines, elongated in males and used for fighting for mates or for defense against predators. The males shed their antlers annually which re-grow through a phase called ‘velvet’.

Muntjac doe in Huai Kha Khaeng

They are the oldest known deer, appearing 15–35 million years ago, with fossil remains found in Miocene deposits in France, Germanyand Poland. The present-day species can be found from Sri Lanka to southern China, Taiwan, Japan (Boso Peninsula and Oshima Island), India and Indonesia. They are also found in the eastern Himalayas and throughout Indochina. There are twelve species of muntjac and they all show similar traits.

Two species of muntjac live in the forests of Thailand; the most common is the red muntjac found in many protected areas throughout the Kingdom, and the other anomaly is the very rare Feas’ muntjac still thriving in the West. Both species are similar in size and behavior, and remain solitary for most of the year except during breeding season. Muntjac feed on leaves, buds, seeds and twigs, as well as fallen fruit. They visit mineral deposits daily to supplement their diet like other even-toed ungulates including sambar, wild pig and gaur.

Muntjac buck in Khao Yai on the grassland

I have photographed barking deer on many occasions at just about every location I have ever visited over the last 15 years as a wildlife photographer. I have also camera trapped many. No matter how many images I have of muntjac, I still continue to shoot these delicate deer always looking for the better shot. Some of my best photographs have come from Khao Yai National Park as seen in the lead photo. My good friend Coke Smith recently managed to catch a female Fea’s muntjac in Kaeng Krachan National Park seen in the story. He was lucky as they are tough to see, let alone photograph.

Fea’s muntjac in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Unfortunately, both species of barking deer are taken for the pot. Their antlers even though small in comparison to sambar trophies are still collected. Poaching is a serious threat to muntjac and needs to be stamped out completely. However, this will more than likely be an on-going problem. The Fea’s muntjac status is ‘Near Threatened’ on IUCN’s list but the Red muntjac is not currently at risk though declining owing to excessive hunting and habitat loss.

Female barking deer on the run in Huai Kha Khaeng

Although some improvement has been made in forest protection by the Department of National Parks (DNP) poachers still continue to evade the rangers and stories pop-up in the newspapers, radio and TV all the time. Heavier fines and long jail time for law-breakers is the key. The DNP should up-grade protection with better enforcement, bigger budgets and more personnel needed in this important aspect of taking care of the Kingdom’s protected areas.

Muntjac doe in Huai Kha Khaeng

Hopefully, muntjac will be with us for sometime. However old policies like the treatment of the DNP’s temporary rangers (50 percent of staff) still plagues the department. No pay for months on end from October through the New Year due to a glitch in the system continues to harm the incentive of these tireless men who are the true protectors of the forest.

Male muntjac jumping a motorcycle in Khao Yai

Management is still lost on this most important issue and I say time and time again: fix this problem now so that Thailand’s wildlife and forests can at least have a chance of survival into the future. The ‘temporary’ hired ranger needs to be up-graded to ‘permanent status’ so he has all the benefits of the other 50 percent (permanent and government officials). It is the only way forward!

Red Muntjac – Muntiacus muntjak

Muntjac male in ‘velvet’ in Huai Kha Khaeng

Muntjac is the most numerous of all deer species in Thailand. Its unmistakable bark, which can be heard over long distances, is made when a predator has been detected. These small ungulates are mostly reddish brown to bright chestnut, with a dark brown face and legs. The underside of the tail is white, and when alarmed will flip up like a white flag.

Female on the run in Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary

Only the male has antlers, which are short and joined to a long pedicle or bony base. The antlers are dark brown in color, about 10-15 centimeters in length, and with a short tine about five centimeters long. The females lack antlers and have small bony knobs with a tuft of black hair where the pedicle is on the male.

In some areas they are active during the day, but where heavily disturbed by hunting muntjac become nocturnal. The rut takes place in December and January. After six months of gestation, a single fawn is born. On rare occasions twins may be conceived. These deer are eagerly sought after for meat.

Fea’s Muntjac – Muntiacus feae

Fea’s muntjac female in Kaeng Krachan

Fea’s Muntjac are now considered very rare and survive only in the Tenassarim Mountain range from Umphang Wildlife Sanctuary near the Burmese border in the West, all the way down to Pha Nga in the South.

These delicate creatures have a dark brown coat with a black ringed uppertail and white undertail. The antlers of the male are yellowish and small compared to the common red muntjac, but behavior of the two species is the same.

Fea’s live only in pristine evergreen like in Kaeng Krachan National Park in Phetchaburi province and Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary. Their range in Southeast Asia is very small.

Notes from the field

Male muntjac dead in the Western Forest Complex

A sad day from December 2000, while working in a protected area within the Western Forest Complex, is etched in my memory. A local hunter killed a muntjac in the forest behind his village. It was a young buck and the villagers were ecstatic; fresh meat is always welcome. The men eagerly carved up the carcass. None of the deer meat was sold but shared with the rest of the village. This is called “subsistence hunting” as practised in community forests in Thailand.

But muntjac is protected and these people had just committed a crime. Who was going to turn them in? As a guest of the house, I took a few photographs but kept my mouth shut, knowing that a step in the wrong direction would alienate these people. Rural Thailand can be a tough place sometimes, and after more than three decades of living here at the time, I felt silent discretion was the best option.

Muntjac being carved-up in a protected area in the West

The biggest problem with community forests is poor or no enforcement at all. Local villagers and hill-tribe people take animals from the forest for self-consumption, or for sale. It is hard to blame them when they live off the land, maybe as their forefathers did or out of necessity, because they are poor and scratch out a meagre living.

Modern life influences people. Many have increased desires relating to modern living habits: new homes, cars and pickup trucks, televisions, mobile phones, computers and video games, etc. The list of consumer items that people want is big and many struggle with debt. Living off the land is free for the taking, so why not take advantage of it? But small and large ecosystems are struggling to survive as humans take all and leave little.

The problems and dangers of the ‘Community Forest Bill’ are quite simple. Just one example: Close to a protected area in Uthai Thani province, a school was responsible for a small patch of forest under the Community Forest Bill. This forest had barking deer, wild pigs, jungle fowl and other small creatures. The teachers and students faced gun muzzles when villagers from afar, who had already depleted their own forests, came to hunt and gather.

Nobody could stop them. Unfortunately, shortly after this incident, wildlife in the small forest was completely wiped out by a few selfish people. The school project, planned to instil conservation awareness among local children and people, failed to even get off the ground. This is a sad fact of life if “firepower” is allowed to dictate who does what, and the consequences were devastating for the school.

Most community forests outside protected areas are virtual islands protected by local communities, rather than the central government. Some are adjacent to protected areas and have unmarked boundaries. Now that the bill has been passed, most people living in national parks and wildlife sanctuaries can take what they want from the forest if they “misinterpret” the law.

Some people and NGOs fiercely contest the ideology behind it. There are some successful programs in which people responsible for a local forest truly protect it from outsiders, but these are few and far between. The road to extinction for many species will undoubtedly speed up. All humans have a right to exist, but unfortunately, not at the expense of the natural world.

Saving a species like muntjac from extinction should be a top priority of the DNP. Other ungulates like goral, serow, wild pig and banteng should be reintroduced into protected areas where they once thrived. Some may argue against reintroduction, but as we lose more and more species, release is the only practical way to save Thailand’s rare creatures from extinction in the wild.

Khao Yai: Thailand’s first and most famous national park

A World Heritage Site in the Northeast

Khao Yai – ‘The Big Mountain’

The concept of parks or wildlife sanctuaries in Siam dates back to the 13th century Sukhothai Period during the reign of King Ramkhamhaeng the Great who created a park known as ‘Dong Tan’ used for royal recreation and preservation. The people were also encouraged to set-up parks around Buddhist temples and other religious sites because it was against Buddhist strictures to take a life and hence all parks were havens of safety for the animals of the forests. However, from the end of the Sukhothai Period to the 19thCentury, parks and conservation declined.

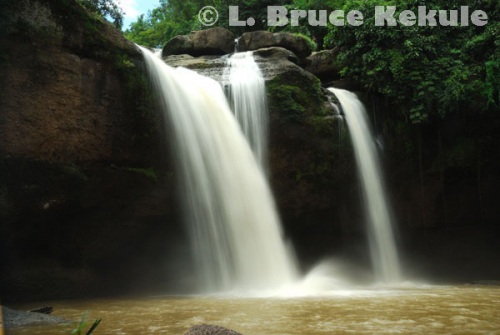

Haew Narok Waterfall in Khao Yai National Park

The Royal Forest Department (RFD) was established in 1896, introducing modern management practices to forestry, especially the teak industry. However, conservation fields were not addressed in the beginning. In 1900, the first law protecting animals was the Law Governing Conservation of Wild Elephants, and thus elephants became the first species protected by a law. In 1921, the law was amended, which superseded the previous act providing better protection.

Haew Suwat Waterfall in Khao Yai

Then in 1943, the RFD began turning its attention to conservation and efforts to manage certain forests for the public’s recreational use. The department established Phu Kradueng National Park in Loei province. However, due to World War II and very limited budgets and trained personnel, the park project was shelved.

Tusker in a mineral lick close to the road in Khao Yai

In 1959, Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat, Thailand’s prime minister, voiced his opinion about protecting some of the immense forests that existed in the Kingdom at the time. He made several inspection tours into the wild areas of the North and Northeast, and became impressed with the natural resources. His idea was to establish reserved areas much like Yellowstone National Park in the US and Kruger National Park in South Africa. His foresight has developed into one of the largest concentrations of protected areas in the world. At last count, there are more than 260 national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, non-hunting areas and marine national parks, plus 1,221 reserved forests situated throughout Thailand.

Tusker near the road

Sarit’s fascination with nature prompted him to establish the National Parks Committee and the Wild Animals Reservation and Protection Committee to hash out necessary protective management plans, and to select pristine wilderness areas suitable for preservation. The first new step to conserving wildlife was the enactment of the Wild Animals Reservation and Protection Act of 1960. The next law passed by legislation was the National Park Act of 1961, which really got the ball rolling. By Royal Decree, on September 18, 1962, the 2,165km2 Khao Yai National Park was appointed, becoming the nation’s first national park, thanks to Sarit and many others.

Muntjac munching on leaves by the road

The core group was made up of General Surajit Jarusaraenee, the Minister of Agriculture and General Prapas Jarusatien, who was the Minister of Interior, along with Chalerm Siriwan, the director general of the RFD and Pramual Unhanand, who was the director of the Bureau of Silviculture under the RFD. The first chief of the park was Boonlueng Saisorn. One man who was also involved in the establishment was Dr Boonsong Lekagul, who was the executive-director of the Association for the Conservation of Wildlife that was actually started up in 1951.

Muntjac male by the road in the park

Dr Boonsong, a well-to-do Thai medical physician, was also a hunter and biologist. He published scores of scientific papers and books on mammals, birds and butterflies found in Thailand. His enormous contribution to natural science was the first stepping-stone to knowledge of the natural world and a better understanding about Thai fauna. Dr Boonsong also collected wildlife specimens to document as many species as possible. He certainly made an impact on the movement of wildlife conservation.

Sambar stag in the campground

Dr George C. Ruhle, an American national park expert from the U.S. National Park Service did a survey in 1959-1960 and a report in 1964 for the ‘International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources’ (IUCN), and the American Committee for International Wildlife Protection’ about the forests. This work contributed to a greater understanding of Thailand’s natural heritage. He made many treks into the wilderness areas of Khao Yai, Thung Salaeng Luang and Doi Inthanon plus many others, and was instrumental in some of the first ‘national parks management plans’ that were to follow.

Banded Kingfisher by the campgrounds

After World War II, about 70 percent of the country was still covered in thick vegetation with an amazing array of wild animals and ecosystems. The first big area to be acknowledged was the primaeval contiguous forest once known as Dong Phaya Fai (or “Jungle of Fire”). This remarkable wilderness stretched from the lower Northeast all the way into Cambodia, and north to parts of the Central and north-Northeast regions. These mountain formations were created during continental uplift about 60 million years ago when the Indian Plate crashed into the Himalayas.

Pig-tailed macaque by the road

Kouprey, a rare wild cattle and now most likely extinct, lived in parts of this great forest. Large tigers preyed on abundant deer and other ungulate species that proliferated in the deep jungle. Smaller species, including clouded leopard, sun bear, gibbons, hornbills as well as many others were common. It was an impenetrable and dangerous place due to the steep mountainous terrain where no roads existed. Very few humans lived in the depths of this once great biosphere. Malaria and fierce creatures reigned supreme.

Great hornbill a its nest by the road

Before Khao Yai was formed, settlers and outlaws used slash-and-burn agriculture in the mountains, creating huge grasslands around the present-day headquarters area. Many of these people were evading the police, but they were evicted after the park was established. The government decided to establish a golf course on the grassland and bungalows to generate income, which was run by the Tourist Authority of Thailand (TAT). Back in the mid-1970s, I actually played golf on the links when it was opened to visitors. It was amazing seeing all those wild animals crossing the fairways. However, the “rough” was jungle, and if you did not hit the ball straight and true, it was a goner! It was a tough course to play on and I lost quite a few balls. It was, however, finally closed in 1991 at the urging of the Anand Panyarachun government.

Male muntjac jumping in front of a motorcycle at khao Khiew

In 1955, a road (Mittraphap Highway: Saraburi to Nakhon Ratchasima) was cut through the forest to facilitate the US military machine at the airbases in Nakhon Ratchasima, Udon Thani and Ubon Ratchathani provinces, as well as Phanom Sarakham district in Chachoengsao province in the Northeast. Later, another road separating Khao Yai and Thap Lan (Route 304: Kabin Buri to Pak Thong Chai) was constructed.

Muntjac jumping 2

These roads basically cut all migration routes of elephant, gaur, banteng and other large mammals established over thousands of years, and opened up virgin forest to settlement. In the meantime, Khao Yai was being encroached on from all sides and can be seen today as resorts, golf courses and agriculture that completely surrounded the park.

Muntjac jumping 3

Khao Yai (“Big Mountain” in English) is part of the Dong Phaya Yen-Khao Yai forest complex covering 6,152km2, and is also Thailand’s second World Heritage Site, which was granted on July 14, 2005 by Unesco. The complex is comprised of five protected areas – Khao Yai, Thap Lan (1981, 2,235km2), Pang Sida (1982, 844km2) and Ta Phraya (1996, 594km2) national parks, and Dong Yai Wildlife Sanctuary (1996, 312km2).

Tusker and tourist bus on the road – a dangerous situation

Khao Yai is Thailand’s third largest national park and covers four provinces including Saraburi, Nakhon Nayok, Prachin Buri and Nakhon Ratchasima (Khorat). It incorporates parts of the Sankampaeng range made up of shale and sandstone at the south-east edge of the Khorat Plateau. The highest peak is Khao Rom at 1,365m and vegetation includes moist evergreen, dry evergreen, hill evergreen, mixed deciduous, dry dipterocarp, secondary forest and grassland. Some formations in the park go back more than 100 million years when dinosaurs roamed here. One set of dinosaur footprints has been found in Khao Yai on an isolated slab of red sandstone by the banks of the Sai Yai River. Some dinosaur fossils have been found close by in Thap Lan and Pang Sida national parks to the east.

Tusker on the road in the late afternoon

Today, elephants, gaur, sambar and muntjac (common barking deer) are still common, but unfortunately, only survive around the Khao Yai headquarters area for about 300km2. Years and years of degradation and poaching have taken its toll imploding towards the centre. Very few animals or birds survive in the outlying areas after many wildlife surveys done by various organisations and individuals came up with data to confirm the void. Even though Khao Yai was the first national park, it certainly has been devastated by years of minimal protective management and prolonged encroachment and poaching.

Tusker charging my truck – reverse was the only option

However, much research, training and management planning has been carried out in Khao Yai, primarily around the headquarters area. One of the first people in 1975 was Dr Chumphon Ngampongsai, who studied habitat relation of the sambar. Secondly, Dr Warren Brockelman of the US and some of his students from Mahidol University have conducted what is now the longest primate study in the world at “Mo Singto Forest Dynamics Plot” of the intricate lives and habitats of both white-handed and pileated gibbons that live together and sometimes produce a hybrid of the two species.

Philip D. Round and George Gale also carried out a bird survey in the plot. In 1978, a hornbill ecology research team under Dr Pilai Poonswad began hornbill surveys and helped increase nest sites. In the 1980s, Dr Surachet Chettamas from Kasetsart University wrote a Khao Yai park and recreation management plan, and Robert Dobias from the US also did planning at that time.

In the late-1990s, a master student, Sean C. Austin from New Mexico State University, did a survey for sympatric carnivores such as the leopard cat, clouded leopard, Asian wild dog and binturong, as well as radio-collared quite a few of them. He also used camera trap technology to build up a database.

In 1999, “Wild Aid”, now known as “Freeland”, started the Khao Yai Conservation Project including community outreach, wildlife monitoring, ranger training and park management in partnership with the Department of National Parks, and the Wildlife Conservation Society who did camera trapping and managed to catch a few tigers on film plus a multitude of other creatures.

Wild Aid also set up a team to monitor the park’s wild elephants and provided some equipment to the rangers. Another master student, Kate Jenks, from the Smithsonian Institute carried out a camera trap programme that involved an attempt to photograph carnivores in conjunction with Wild Aid from 2004 to 2007. Sadly, she camera trapped no tigers during the program but did record one set of tiger footprints in 2005.

Dr Naris Bhumpakphan of Kasetsart University sent master student Preecha Prommakul to monitor and camera-trap tigers in Khao Yai, but with a lack of data, the program was shelved. Preecha did, however, see a set of tracks around the back of a camera trap, indicating a tiger was possibly avoiding the traps.

Unfortunately, it looks as though the tiger has probably disappeared from the park. These magnificent cats have not been seen or recorded for some time now and no camera trap photos have been collected of tigers since 2001. However, reports of sightings and tracks do come in from time to time, but these are now rare. If leopards once thrived here, it was a long time ago.

Asian wild dogs are now at the top of the food chain. A large pack of more than 20 dogs devouring a sambar in one hour has been observed by a tour guide and the rangers. These pack animals are ferocious carnivores and once a feeding frenzy has begun, it’s every dog for itself. They have been consistently seen and photographed around the headquarters area.

Khao Yai is one of the best places to see wild elephants up close during the day or night. These giants can be seen along the road down to Nakhon Nayok, but from the safety of one’s motor vehicle. They also can be seen at the mineral licks set up on the grasslands. It is definitely recommended not to exit your car and strike out on foot as the elephants can become irritated and things could get dangerous, especially an encounter with a bull in musth, or a mother with a baby. Bull elephants in the park have killed several Buddhist monks in the forest meditating.

A birdwatcher friend of mine took his family out one night and was surrounded by a herd of elephants on the road. These gentle giants dented his van, costing him thousands of baht in repairs, and scaring the heck out of them while they sat motionlessly waiting for the herd to pass.

The most famous waterfalls in Khao Yai are Haew Narok, which takes a hike of about one kilometre and Haew Suwat, not far from the road. During the rainy season all of the rivers in the park become raging torrents. Quite a few elephants have been washed over the falls at Haew Narok and killed during heavy rain with swollen rivers. A temporary ranger station has been set up to ward off any elephants trying to cross during a heavy surge. There are more than a dozen marked nature trails covering about 50km for the adventurous type, but it is advised to hire a guide from the park as some are ever-changing and one could get lost in the dense forests.

During the rainy season, leeches and malaria mosquitoes are a problem. During the dry season, ticks can be irritating and dangerous to one’s health as some carry diseases. Insect repellent, leech socks and heavy clothing are the best way to ward off the bothersome creatures. But seeing the exotic mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians, butterflies and other insects in their natural habitats, plus the beautiful flora is still quite good and worth the effort.

The best time to visit is during midweek. Make your bookings in advance with the department’s online website for accommodations. Food and services are good but close shop at around 6pm. One of the biggest problems facing Khao Yai is the over-abundance of visitors during the holidays and long weekends, plus excessive spotlighting during these times. There is quite a large number of buildings, bungalows and campsites, and rubbish can be a problem for the park.

Many deer and other animals have perished from foam and plastic intact by eating discarded food containers. Khao Yai as Thailand’s first national park should be a role model for all other conservation areas. Given this important heritage, increased efforts by those responsible need to be made to save this magnificent biosphere. It is a fact that, with good protection, animals and plants will make a comeback. The park has the potential and we the people need to ensure its future survival.