Posts Tagged ‘pig-tailed macaque’

Pig-tailed Macaque in Mae Lao-Mae Sae Wildlife Sanctuary

A mature pig-tailed macaque up on a ridge-line in the sanctuary

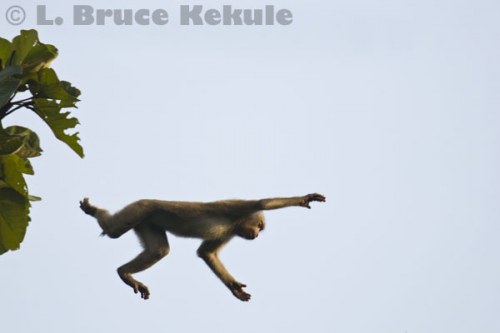

This monkey showed-up in front of a Bushnell Trophy Cam set to video, and then made an amazing leap to a tree overlooking the lower valley. As a loner or solitary primate, he must have been pushed out of the group by a larger male. But the big question: What was he doing all the way at the top of this mountain?

Thailand’s Primates: Terrestrial and arboreal mammals

Wild Primates: Gibbon, macaque, langur and loris

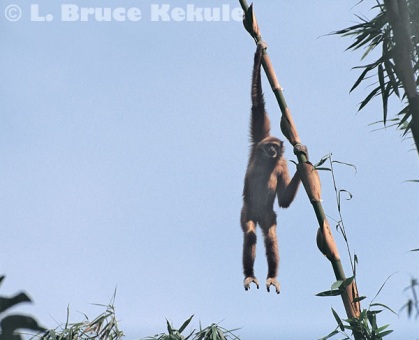

Gibbon hanging from bamboo in Kaeng Krachan National Park

During the Miocene Epoch (5.3-23.8 million years ago), a relative of the orangutan ape lived in the dense jungles in what is now north and northeast Thailand. Scientists digging in coalmines and sandpits have produced some very amazing fossils.

Other primates like a 13-million year old tarsier and an early Adaptiform primate have also been found in the Kingdom. The oldest anthropoid from the fossil record is Siamopithecus eocaenus, or known as ‘Siam Ape’, and found in 40 million year old strata in Krabi province down South. This legacy is just another part of Thailand’s remarkable natural heritage.

Pig-tailed macaque in Khao Yai National Park

In 2003, an extremely important discovery was made by paleontologist Dr Yaowalak Chaimanee of the Department of Mineral Resources in a lignite mine near Chiang Muan district in the northern province of Phayao. Fossilized teeth of a hominid primate about 10 to 13.5 million years old, was brought forth. The ape was first named Lufengpithecus chiangmuanensis and is related to orangutans. It has latterly been reclassified and renamed to Khoratpithecus chiangmuanensis all because of another amazing new discovery.

In 2004, a new species of fossil orangutan about 7-9 million years old was dramatically uncovered on the Khorat Plateau in Nakhon Ratchasima province. Thailand once again found itself on the world’s paleontological map. The new ape was named Khoratpithecus piriyai (ape from Khorat) after Piriya Vachajitpan, who played a major role in the discovery at the Tha Chang sandpits in Chalerm Phrakiat district. The lower jawbone and teeth have a U-shaped dental arcade similar to that of a living ape – and of human beings.

Crab-eating macaque in Sai Yok National Park

Modern orangutans hail from the Pleistocene era, from 2 million to 100,000 years ago. Their geographic distribution once included much of Southeast Asia. However, they became extinct from many areas because of deforestation and hunting. Today, the orangutan can only be found in Borneo and Sumatra.

The orangutan is the only great ape with a fossil record. Strangely, no African fossils have ever been found that are related to chimpanzees or gorillas. But determining the ancestry of the orangutan has still proven extremely difficult.

Dusky langur in Kaeng Krachan

Dr Yaowalak has also discovered other primates like Siamoadapis maemohensis, a primitive primate. A new species – named Tarsius sirindhornae (named after HRH Princess Sirindhon) – that lived about 13 million years ago has also been found. Tarsiers are primates that share a common ancestor with monkeys and humans.

Primates started evolving more than 50 million years ago during the Eocene when mammalian evolution accelerated. A newly found species small enough to fit in the palm of a hand is North America’s oldest known primate, according to a new study. Christopher Beard, a paleontologist at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, recently discovered fossils of the 55-million-year-old creature on the Gulf Coastal Plain of Mississippi.

Slow loris in Kaeng Krachan

Named Teilhardina magnoliana, the animal is related to similarly aged fossils from China, Europe and Wyoming’s Big Horn Basin and is the oldest primate ever discovered. They are very primitive relatives of living primates called tarsiers, which live today in Southeast Asia.

A new kind of primate that lived 43 million years ago has been discovered in the Big Bend region of West Texas. Named Mescalerolemur horneri, it was among the last primates endemic to North America. This petite creature, weighing just 370 grams, is related to modern-day lemurs found only in Madagascar.

Pileated gibbon male and female in Khao Ang Run Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

The Primate order includes tarsiers, lemurs, lorises, monkeys, gibbons, large apes and humans. Also known as simians, the sub-order Anthropoidea is comprised of apes and humans, and New and Old World monkeys.

Some scientists now believe that some hominoid primates evolved in Asia, possibly in parallel with Africa. A faunal dispersal corridor is believed to have existed between Southeast Asia and Africa during the Middle Miocene. Fossils of human species Homo erectus have been found both on the island of Java and in China. Many new hotly debated theories have erupted within scientific and academic circles.

Crab-eating macaque in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary

Wild primates in the Kingdom include slow loris and various macaques, langurs and gibbons. Most live in the forests of protected areas. Populations are dwindling, however, as forest habitat is slowly destroyed and unsurped by humans. The future of wild primates is on nature’s balancing beam. They only really survive in the top national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and reserved forests where there is little human influence and disturbance.

Undoubtedly, among the world’s most charismatic and vocal members of the rainforest are the gibbons. Their calls are inspirational, beautiful and scientifically fascinating. I once listened to three separate groups calling in mid-morning while trekking through Kaeng Krachan National Park. It was a beautiful moment in my travels through this forest.

Stump-tailed macaque mother and baby in Kaeng Krachan

Once while I was packing-up at the end of the road in the park to go down to the Phetchaburi River, an opportunity to catch a gibbon on film presented itself. This dark-blond white-handed gibbon all of a sudden swung out on a single bamboo and seemed like “here I am and hurry up” as seen in the lead photograph. I quickly got my camera and long lens and rested it on a sandbag at the back of my pick-up. After a few shots, it melted back into the forest. The blue skies, light and subject contrast is a wildlife photographer’s dream.

Four species of gibbon live in the Kingdom: white-handed gibbon, pileated gibbon, agile gibbon and siamang. A few hybrids have been identified where the white-handed and pileated gibbons overlap in forest habitat in Khao Yai National Park.

Dusky langur eating leaves in Kaeng Krachan

If a forest has substantial gibbon populations, it usually means the wilderness is fairly intact. But some suitable forests are becoming as rare as the animals themselves due to the deadly tandem of encroachment and poaching spreading throughout the wild primate range.

Gibbons spend their entire life in the trees. Their whooping calls can be heard over long distances and can erupt at any time during the day or night. Gibbons may start calling at 4:00am in some forests and they usually quiet down after midmorning, although they will sometimes vocalize in the afternoon. Gibbons are very active as the sun rises moving to fruiting trees. The white-handed gibbon, the most common species, is found throughout most of the country while the pileated gibbon survives only in the east. The agile gibbon and siamang live in a small pocket near the Malaysian border.

Dusky langur sitting on a stump in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

There are four species of langur: Phayre’s, banded, silvered and dusky or ‘spectacled’. Known also as ‘leaf monkeys’, they share the same predicament as gibbons. Langurs have slender bodies and limbs, with a tail longer than the head and torso and the species differ in coloring: black, gray, dark brown to reddish with some albino. These monkeys are eagerly hunted for their meat, blood, and for gallstones, which are valued in Chinese medicine. These nimble acrobats live in trees but descend to the ground to eat fallen fruit, drink water and take in minerals. They are one of the most sought after primates.

Five species of macaque are found in Thailand: Assamese, rhesus, stump-tailed, pig-tailed and crab-eating, also known as long-tailed. Macaques are the most common wild primates and some species live near or even within cities, usually associated with Buddhist temples where they have become habituated. Some species live in steep limestone hills and cliffs near human settlements. Pig-tailed macaques beg for food from passing motorists on the road close to the headquarters at Khao Yai. Some people who feed these creatures often receive serious bites, as these monkeys can be vicious.

Leaping langur in Kaeng Krachan

Stump-tailed macaques are probably the fiercest of the five species, living mostly in deep forest far from humans. Males have huge fangs and can inflict terrible wounds. These monkeys are terrestrial creatures foraging for food on the ground. They rarely climb trees, although have been seen in the forest canopy, most often when fleeing poachers and gunfire. Now rare in the wild, stump-tailed macaques are found in a few protected areas.

Slow loris is the smallest of Thailand’s wild primate species. Nocturnal and arboreal, they live in the trees of primary and secondary forest, and also groves of bamboo. These cuddly balls of fur are seldom found on the ground and are renowned for their deliberate, slow hand-over-hand movement while traversing a tree branch. Slow loris can be seen at night on fruiting trees in some of the top protected areas.

Stump-tailed macaque by the Phetchaburi River

Sadly, all these primates are eagerly sought after for the illegal pet trade or Asian medicine trade, and trade in baby gibbons taken from their mothers are an ongoing threat. Macaques are used in the coconut trade (the monkeys are sent up a tree to collect the nuts, usually for a food reward) and some are abused.

Dr Warren Brockelman is widely known as one of Thailand’s top scientists studying primates especially the gibbons in Khao Yai National Park. He established a study plot to monitor the gibbon’s feeding habits and ranging behavior. Other studies included plant-animal interactions and forest community dynamics on the 30-ha ‘Mo Singto’ forest dynamics plot in Khao Yai.

Pig-tailed macaque jumping in Khlong Naka Wildlife Sanctuary

Primatologist Dr Suchinda Malaivijitnond with the Primate Research Unit at the Department of Biology, Faculty of Science in Chulalongkorn University has done a lot of research on primates specializing on the long-tailed (crab-eating) macaques.

Her work in 2005 included surveys of long-tailed macaques at Piak Nam Yai Island, Laem Son National Park in Ranong Province, situated in southern Thailand. Long-tailed macaques found on the island were observed using axe-shaped stones to crack rock oysters and swimming crabs. They smashed the shells with stones that were held in either the left or right hand, while using the opposite hand to gather the meat.

Pig-tailed macaque stealing food in Khao Yai

I have mentioned many times in my stories in the past that the most important issue pertaining to the protected areas is protection and enforcement. If the forests and wildlife are looked after, they will continue to thrive. If poaching and encroachment is allowed to carry on, the Kingdom’s natural ecosystems will decline.

Positive and swift action is the only option for the Thai government in taking care of the natural resources. Better management, up-dated laws and increased funding are most imperative. Only then can the future for all of Thailand’s wild living things be definite.

Crab-eating macaque eating a bag of dry noodles