Posts Tagged ‘Kaeng Krachan’

Keang Krachan: Rare creatures surviving in the park

A collection of photographs taken from 2001 to 2008

of some rare Asian animals still thriving in this amazing forest

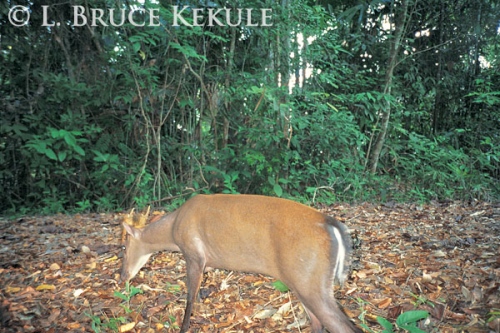

Fea’s muntjac camera-trapped at Kilometer 33 on Phanern Thung mountain

Male muntjac also known as common barking deer at a mineral lick

Male muntjac feeding on leaves

Gaur cow at a mineral lick in the interior

Small gaur herd at another mineral lick

Gaur bull and cow footprint compared to my hand

Asian tapir swimming in the Phetchaburi River

Tapir camera-trapped near the Phetchaburi River

Serow camera-trapped on old logging road

Tusker camera-trapped at a mineral deposit at kilometre 12

Tuskless bull elephant in ‘musth’ camera-trapped on an old logging road

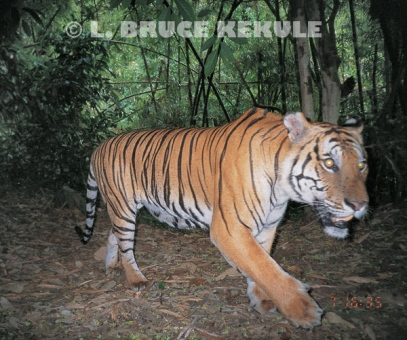

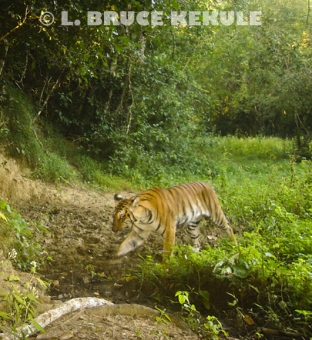

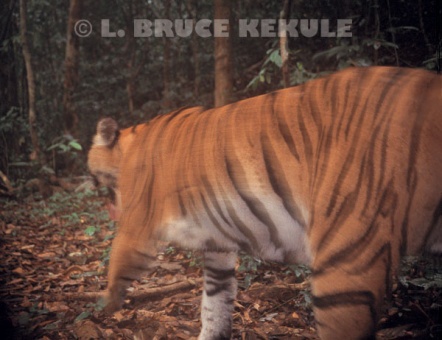

Tiger camera-trapped at a mineral lick in the interior

Indochinese tiger camera-trapped by the Phetchaburi River

Asian leopard camera-trapped on a nature trail

Indian civet caught near Ban Krang campground in the park

Banded linsang camera-trapped on a dry streambed

Banded palm civet camera-trapped by a stream deep in the interior

A king cobra hunting for prey by the Phetchaburi River

A green pit-viper and carpenter ant on a small tree

A green pit-viper swallowing a skink

Reticulated python on the road in Kaeng Krachan

Horny tree frog in a stream deep in the park

Giant tree frog further upstream

Great hornbill flying out of a fruit tree

Oriental Pied hornbill feeding its chicks at the nest

Wreathed hornbill at a nest

Oriental dwarf kingfisher near it nest

Pied kingfishers with a fish on a tree branch

Blue-bearded bee-eater with a beetle for its chicks

Red-bearded bee-eater close to its nest in a sandbank

Black-and-red broadbill with a bamboo leaf

Black-and-red broadbill building a nest

Javan Frogmouth by the Phetchaburi River

Lesser fish-eagle chick exercising its wings high up a very tall tree

Lesser fish-eagle mother and chick on the nest above the Phetchaburi River

Lessor fish-eagle on a tree branch behind my blind over the Phetchaburi River

River carp in the Phetchaburi River

Gibbon hanging from a bamboo on Phanern Thung mountaintop

Dusky langur near the Phanern Thung ranger station

Stumped-tailed macaque by the river

Rainbow over the Phetchaburi River

Kaeng Krachan National Park is an amazing place but is fraught with poor management and protection. There are many other animals and ecosystems not shown here but this place is truly one of Thailand’s greatest protected areas.

It takes lots of hard work to get down to the river and collect photographs of the creatures thriving there. But diligence, determination, the right equipment, money and with good guides, is also within the reach of serious amateur photographers or naturalists who just want to look.

The opportunities are endless. It is hoped these photographs will create awareness and help this place survive into the future, so that generations to come can also enjoy the beauty of nature in Thailand’s largest national park.

My next post will be a collection of photographs from Huai Kha Khaeng like this of that amazing World Heritage Site, and hopefully sometime before I travel to Africa for a safari to Kenya in mid-August.

Photographing three wild species in one day

The beginning of my 3rd book project entitled Wild Rivers

Three species on one lucky day in March of 2005

Like most of my mornings in the forest, getting out of the hammock before dawn is a routine affair for me. Sleeping by the pristine Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan National Park in southwest Thailand is a peaceful and soothing experience with the sound of rushing water flowing down to the lowlands. The night creatures fade into their abodes and daytime is greeted by singing birds and insects. As the sun comes up, gibbons call and hornbills honk from the treetops. It is nature at its very best.

Buffy fish owl by the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan National Park

I adhere to an old saying; “an early bird get’s the worm” to sometimes work wonders. This was the case one particular morning in March 2005. After a quick cup of coffee, I got my cameras ready for the days’ shoot. I was about to embark on my third book project capturing some extremely lucky wildlife photographs of three different species in one day.

The mighty Phetchaburi River during the dry winter season

About 6am, one of the Karen porters went upstream and found a buffy fish-owl stuck in his fishnets. I was upset at them to say the least but had to think quickly. The bird was going into shock as hypothermia took control over the owl. It was on the verge of dying and only quick thinking saved this creature from certain death. The campfire was going well so I placed the bird close to warm it up and get its blood flowing. I’m sure the creature had no idea what was going on but the bird was calm and collective as I assured it everything would be OK.

Buffy fish owl just after being saved from certain death

The owl began to perk up and I knew then it would survive. I placed it on a tree branch by the river and it locked its talons into the bark. The bird of prey just sat there while I played wildlife photographer. After shooting almost an entire memory card and without further ado, I left the owl in peace.

As I sat down to eat breakfast, it left its temporary perch and flew across the river disappearing into the dense forest. The bird was not seen again. I felt pleased at having saved this beautiful creature’s life. I had just switched to a Minolta digital SLR camera and was able to double-check all my shots for exposure, color and focus. Everything looked good and I was excited at having photographed this owl during the day as they are nocturnal.

King cobra hunting along the Phetchaburi River

After breakfast, we packed up our gear for a day trip headed upriver. In March, the water level is low, and the riverine habitat easy to transverse. The team and I crossed the river several times till about 4pm when I decided to turn back to camp. Just then, my research companion Detchart “Top” Saengsen sighted a large snake and called out. I reached for my camera with a 280mm lens and found a slithering black reptile in the underbrush. Its head appeared and I started shooting, not thinking about the danger. The king cobra – the world’s largest venomous snake – moved into an overhang so I flipped up the flash and took a few more shots. The reptile did a u-turn and was gone in a split second.

The big snake just before it made a u-turn and disappeared in a split second

The rest of the team had already retreated, leaving the crazy photographer to his own devices. It certainly was an exciting experience. I was elated that I had just photographed the true king of the forest. It is said large mammals like elephants, gaur and tigers stay out of the king cobra’s way. I checked my camera and had two shots left on my card. I decided not to delete any poor images until later as I felt nothing would show itself after the big snake.

Asian tapir swimming in the Phetchaburi River

The team and I were in good spirits as we headed back to camp. Suddenly, an Asian tapir bounced out of the thick forest on the opposite bank about a hundred meters away. It dove into the river and started swimming towards us, now fifty meters off. Tapir have fair eyesight but this black and white creature did not notice five humans standing out in the open up on a sandbank. I took one shot of the swimming tapir then waited, knowing very well I only had one frame left. The creature got closer and then stopped in the water about 20 meters away. I centered the focusing ring on the eye and took the shot. Then we watched this elegant animal go back the way it had come.

Asian tapir posing for me in the late afternoon sun

I know I missed quite a few shots because of old age, forgetfulness (not having spare memory cards), but then again, the two shots I had were more than enough. I was thrilled to photograph the world’s largest tapir in daylight. These creatures are mainly nocturnal and rarely seen. That day was truly the beginning of a new dream and my last shot of this tapir made the front cover of my third book Wild Rivers now published and available at bookstores in Thailand and the region. It certainly was a special day for me and one that is etched in memory.

I am now working on book four which will be a collection of stories published over a two year period in the Bangkok Post, Thailand’s number one English daily. Chapters about the top protected areas in Thailand and ‘wild species reports’ on the animals thriving in the remaining forests including mammals, birds, reptiles, insects and other categories. Hopefully, this book project will create conservation awareness among the present generation. My dream to produce wildlife books continues, but that is another story.

The Asian Leopard: Thailand’s second largest cat

WILD SPECIES REPORT

An ambush predator – solitary, stealthy and naturally camouflaged

The late French poet Robert Desnos (1900-1945) wrote a short poem entitled “The Leopard”

“If you go into the woods, beware of the leopard.

He meows in subdued voice and arrives from nowhere”

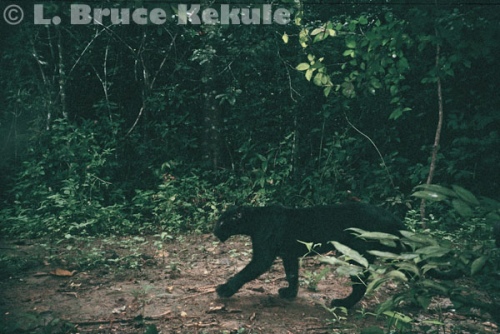

Black leopard in the late afternoon sun

The leopard Panthera pardus described by Linnaeus in 1758 is the second largest cat in Thailand. Once upon a time, leopards could be found in all the forests of the Kingdom. These felines are still surviving quite well in protected areas in the West, and some in the South. The central, eastern and northeastern regions have no reports of leopard for some time now.

A few have been reported in Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary in Chaiyaphum province, but for some reason they have disappeared from most remaining forests. The reason these areas have no leopards are quite simple; prey species has been hunted out including the leopard itself for its pelt and bones, and encroachment has destroyed much of its habitat.

Sighting a leopard in Asia is extremely difficult, and even catching a rare glimpse of this very essential top predator is tough due to its solitary and stealthy behavior. However, luck can sometimes play an important part in viewing the leopard and I feel lucky to have seen and photographed them on quite a few occasions.

Leopard camera trapped in Kaeng Krachan National Park

The most thrilling or heart stopping adventure with a black leopard happened in Huai Kha Khaeng about five years ago while I was sitting up on a bluff overlooking the river. A photographic blind was erected on the rock-face about 20 meters up with a small trail that enabled me to get into the hide. It was a neat location that I had dreamed of sitting here for many years prior. The sun was bright and the weather was warm during the dry season.

About 9am, several monks down by the river passed on but did not see the camouflaged structure as they went their way. After that, I came down for lunch and set some camera traps at a mineral deposit nearby. At 2pm, I settled back in the blind and began a vigil of the river. I started to feel a bit groggy as the sun was beating down on my position. I moved my camera in to save it from the direct sunlight.

All of a sudden, I was startled by a guttural growl outside the enclosure. I stood up slightly and peering out the window came face to face with a huge round black head and yellow eyes about two meters away that penetrated my soul. My first instinct reaction; it was a big black dog. But that quickly changed as the creature stared intently at me before bounding down the trail it had come up. The big cat was gone in a split second. Of course there was not enough time to get any photographs. The incident surely is etched in my memory.

Black leopard camera trapped in Kaeng Krachan

Why had the leopard come so close without smelling me? On that particular day, I was using an old hunters technique by collecting fresh wild water buffalo droppings and putting them in front of the blind, and that probably covered my scent. Maybe the leopard thought there was a newborn calf, or an old weaken animal. Or maybe it used this natural place overlooking the river to spot prey like sambar, barking deer or wild pigs that are abundant here and came up to investigate. The vantage point is on a bend in the river and one can see for quite a distance both ways.

I will never know how close I came to being attacked by a leopard but it was a heart stopper for sure. I sat motionless for quite sometime. Only a few sticks and camouflaged material separated me from a wild creature armed with fangs and claws. On that day, the spirits of the forest looked after me, or was it the ‘Spirit of the Forest’. I like to believe that was the case. I hope one day to go back and stake out this bluff, and believe this leopard is probably a resident around here. Previously, I camera trapped tiger and a yellow phase leopard not far from here.

A leopard resting on a wildlife trail

Speaking of leopard attacks, my close friend and associate Dr Lon Grassman was once seriously injured in Kaeng Krachan National Park, Phetchaburi province by a leopard while working there on a survey to camera trap and collar the big cat. When Lon released one, it looked up and turned on him in a split second mauling his legs and arms. It was a close call but he survived to carry on his work researching wild carnivores. Lon established the home range and other behavior patterns of leopards in the park.

He then moved to Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary, Chaiyaphum province in the Northeast and continued this work catching and releasing quite a few golden cats, clouded leopards and a marbled cat. He eventually received his doctorate for his excellent work.

In the beginning of my profession as a wildlife photographer, I was very fortunate. The Director of the Wildlife Conservation Division of the National Parks Department (DNP) at the time, my dear friend Dr Viroj Pimmanrojnagool (now retired), had confidence in me and gave permission to enter the realm of the leopard and the tiger, something not easily acquired. Entry into wildlife sanctuaries has always been very restricted but is possible with the right qualifications. Viroj and I are still very close and I visit him from time to time at his durian farm in Surat Thani down south where he is happily enjoying retirement.

Leopard in the bamboo – my very first photo of the big cat

My first encounter with the sleek cat goes back to the beginning of my career more than a decade ago. Driving into the forest late one afternoon in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, a World Heritage Site, the sun was low but the light still quite good for photography. The protected area is situated in Uthai Thani province and is part of the Western Forest Complex.

I was about to capture my very first Asian leopard on film. This was in my early days as a wildlife photographer with a newly acquired Nikon N90s camera and 300mm lens. I was on a learning curve that would take me into some unique natural habitats and bump into some very unusual animals around Thailand.

Leopard posing in Kaeng Krachan

About 4pm some 10 kilometers from the headquarters as I was driving in, a leopard jumped in front of my truck and bounded up the steep embankment on my right. I gently came to a halt and there looking down at me was these two big yellow eyes that brought my attention to 100 percent. In the meantime, I had already grabbed my camera and started snapping through the window as fast as possible but quickly slowed the pace concentrating on focus. After a few more shots, the spotted cat melted into a bamboo thicket and was gone. The encounter was measured in mere seconds.

I sat in the vehicle for a few minutes to catch my breath as my heart was thumping. A close encounter with a carnivore capable of tearing us apart is something that can get the blood flowing. I finally got going again as my destination was still a couple of hours away deep in the forest.

Leopard on a sambar kill – my first camera-trap photo of the feline

Arriving at the Kabook Kabieng ranger station just at dusk, the head of the station Loong Waitanyakarn, another good friend, came immediately to the truck and said, “ a sambar mother and fawn have been killed by a leopard or wild dogs not far from the station and let’s go look”.

It didn’t take me long to ponder that an opportunity had presented itself. I had a new infrared sensor for my Nikon camera and decided to set-up the unit next to the dead sambar. A new role of film was loaded and the lens focused on the mother deer. The sensor was active infrared that uses a transmitter and receiver hooked to the camera. When an animal trips the beam, the shutter is activated taking a self-portrait. At the time, this technology was rather new but I needed it to supplement my regular photography.

Black leopard posing for me at a hot spring

The next day at noon some 10 kilometers away, Loong took me to a tree stand over-looking a hot spring. The box-like structure was quite high up and it was a bit scary getting situated in the blind but finally, I settled down with my Nikon 500mm lens and camera scheduled for a three-day stint. The mineral deposit and hot springs attracts many large mammals including elephant, gaur, banteng, tiger, leopard, wild dogs, tapir and many other animals that come for the life-giving minerals, or for prey.

Black leopard at the hotspring

About 3pm, a troop of leaf-monkeys visited the hot springs for a quick drink but did not stay long. They had been spooked by something as they all panicked and gave flight in the trees up the hill. A short time later, a black leopard appeared from the top end and walked over to where the monkeys had just been. The sun was low in the sky and I could see the leopard’s pattern of rosettes through the lens that jumped out at me.

My heart began racing as the stealthy cat stopped at the top to take a drink. It stayed for about an hour. I calmed down but continued shooting changing several rolls of film and watching this magnificent creature. Just before the sun was gone, it moved closer to the tree I was in and then walked across the stream. The cat plopped down on a log and stretched out posing for me, all the while looking up at my position. I kept shooting and then it came even closer before veering off probably spooked by my scent. As the leopard moved through the forest, monkeys, barking deer and sambar barked at the predator.

Leopard mother and cub camera trapped at a sambar kill – A rare photo

showing both color phases

I will never forget these encounters. Three leopards in two days are pretty good going for a new wildlife photographer and it was truly the beginning of many sightings and photographs of this amazing carnivore. I have seen loads of them on film while working in Kaeng Krachan. Both black and yellow phase were camera trapped in three separate locations in the interior at almost every location.

The Tenassarim Range in southwest Thailand is an absolute haven for the leopard due to a very good prey base here. Tigers also survive and have overlapping territories with the spotted cat. Both species hunt during the day and night. My old friend Suthad Sapphu, a forest ranger in Kaeng Krachan, was extremely helpful while we were camera trapping the big cats.

Leopard track in Kaeng Krachan

Without doubt, the future of the leopard depends on one thing only – the complete protection of the remaining forests where they live. If the national parks and wildlife sanctuaries remain intact with a high number of prey species, the big cats will survive. But if over-development, poaching and encroachment are allowed to continue, the large cats will eventually disappear.

Unfortunately, too much time and money is wasted by too many organizations talking about saving wildlife and their habitats, with very little actually being done. Human population growth will eventually destroy most wild places. Only true protection by some dedicated people will slow the destruction of nature’s precious wildlife and wilderness areas. It is hoped the leopard, and the tiger, will continue to survive as they have for millions of years.

Leopard Ecology:

Pound for pound, the leopard can take on some seriously large animals several times its size. The leopard is closely related to the jaguar of South America. Both have a spotted coat pattern, incidence of ‘melanism’ or black phase, and relatively short legs.

The present distribution of the leopard is restricted to Asia Minor, India, Southeast Asia, the Himalayas, Tibet, China, Siberia, and Africa. Fossils of leopards were found in Pleistocene deposits throughout Europe, the Middle East, Java, and Africa, some 1.5 million years old, indicating the leopard arrived after the tiger. These secretive cats are mainly nocturnal but in some localities, they are active in the day too. Their populations and ranges are difficult to determine but radio tracking of collared animals has shed new light on their movements and areas they live in.

Black leopard camera trapped in Kaeng Krachan

The leopard is a member of the Felidae family and is the smallest of the four “big cats” in the genus Panthera, or roaring cats. The other three are the tiger, lion and jaguar. The leopard’s range of distribution has decreased radically because of hunting and loss of habitat. It is now chiefly found in sub-Saharan Africa; there are also fragmented populations in Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Indochina, Malaysia, and China. Because of its declining range and population, it is listed as a “Near Threatened” species by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature).

The species’ success in the wild is in part due to its opportunistic hunting behavior, its adaptability to habitats, human settlements and activity, its ability to run at speeds approaching 58 kilometers per hour (36 mph), its unequaled ability to climb trees even when carrying a heavy carcass, and its notorious ability for stealth. The leopard consumes virtually any animal it can hunt down and catch. Its habitat ranges from rainforest to desert terrains.

Big Cats in Kaeng Krachan: The tiger and leopard

A look at tiger and leopard evolution in Asia

At the beginning of the dry season in January, the jungle canopy is still mostly green but falling leaves begin to carpet the forest floor as the first cold snap arrives. Some species of trees start their transformation, producing a mosaic of yellows, oranges, reds, browns and greens. For the first few hours each morning, heavy fog blocks out the sun as moisture dissipates from the forest. The Phetchaburi River is crystal clear as it flows through this magnificent forest.

Indochinese tiger camera trapped by the Phetchaburi River

A large predator walks the trails seeking its next meal. Sensing danger, a muntjac barks a warning. The whole community of wild animals is on alert as macaques and langurs cry out from the trees above. A striped carnivore stalks a herd of wild pigs. The nervous omnivores squeal and panic, running through the underbrush to escape. But the big cat is lightning quick – it catches a young pig with sharp claws. The struggle is over in seconds as fangs penetrate to the spine.

Leopard camera-trapped on an old logging road

The tiger has just made a kill. It lifts the lifeless prey into deep cover and devours the carcass. After feeding, the big cat seeks water for a thirst quenching drink. It will then lie down and rest until the desire to eat or drink begins again. Tigers will sometimes move great distances in search of food. But where there is an abundance of prey species, these magnificent cats continue to live in balance with nature. The average kill ratio for a tiger is about twenty unsuccessful attempts for one actual kill. At a certain time of year, the male tiger will seek out a female to carry on his legacy.

Another tiger by the Phetchaburi River

Kaeng Krachan National Park is a great wilderness that sits in the Tenassarim Range in southwest Thailand. It is one of the most beautiful protected areas left in the country. Elephants, gaur, tiger, leopard, tapir, gibbons, hornbills and literally thousands of other plants and animals still survive in a rich ecosystem that is world class.

A tiger camera trapped at a mineral lick in Kaeng Krachan

To understand how the tiger and leopard evolved, we must go back to the beginning of these wild creatures. After the carnivorous dinosaurs died out about 65 million years ago, mammals with sharp teeth, strong jaws and claws replaced them as the top land predators. The first successful mammalian carnivores were the Creodonts that evolved during the Eocene epoch 57-35 million years ago. Creodonts ranged in size from smaller than a weasel to as big as a bear. A bear-dog also evolved during this period. These carnivores all had voracious appetites that were satisfied by large concentrations of prey species, mainly the odd-toed and even-toed ungulates that browsed and grazed the lush forests and plains of the time. The early Creodonts evolved into the modern carnivores that we know today: the bears, cats, dogs and other predators.

Tiger camera trap abstract

The order Carnivora is separated into three superfamilies: The Arctoidea includes marten, weasel, badger, otter, bear and the panda; the Cynoidea are made up of the dog, fox and the wolf; and the Herpestoidea includes the mongoose, civet, hyena and the cat. Most carnivores are dedicated meat-eaters, but some groups such as civet, panda and bear are omnivorous, eating meat and plants.

Leopard camera trapped on a nature trail in the park

Nimravidae were the first cats to evolve in the Early Oligocene epoch, about 35 million years ago. They lasted till the Late Miocene, some eight million years ago, when huge grasslands had developed around the world. The large saber-toothed cats were the first of the family Felidae. These long-fanged felines evolved alongside huge herds of grazing mammals like antelope and cattle. There were several different species of saber-tooth, but they all became extinct about two to three million years ago.

Black leopard camera trapped on the main road in the park

Modern cats belong to the family Felidae and include: tiger, lion, leopard, jaguar, cougar and cheetah, and all the smaller cats such as lynx, bobcat, jungle cat, fishing cat to name just a few plus domestic cats. Wild carnivores feed almost exclusively on vertebrate prey and sit at the top of the food chain. Tiger and lion have few predators apart from man but a pack of wild dogs however are a constant threat to the large cats and their offspring. The tiger and leopard belong to the genus Panthera, or roaring cats, that include the lion and the jaguar.

Leopard camera trapped in the interior

Thousands of years ago when primitive humans lived off the land as hunters and gatherers, they survived by pure instinct. They killed animals for meat and skins, and also gathered many different tools and plants from the forests. As humans became more sophisticated, they used weapons to take down larger animals. Clubs, spears, knives, bow and arrows were all that separated them from almost certain death at the claws and jaws of a predator many times their size.

Black leopard camera trapped on an old logging road

The possibility of being eaten by a carnivore like a tiger or leopard must have been on everyone’s mind that lived in or near the wilderness. Entering the forest where every step could be the last was like walking a tightrope. Attack normally lasted only seconds as a huge predator pounced from behind, biting the neck and causing almost instant death. Very few people survive such an incident. It must have been a scary environment to live in.

The will to survive, however, was strong and men eventually conquered his fear of the wild cats with more modern weaponry. The tables had finally turned and the predators became the hunted. As human populations and settlements grew, the forests were quickly transformed into agricultural land.

An Indochinese tiger on the prowl at night by the Phetchaburi River

After firearms were invented, European royalty, native kings, landlords, planters, foresters, government officials and many adventurers journeyed to the forests of Asia in search of the tiger. Mostly, they came to prove their dominance over the big cat. A trophy of tiger on the wall or floor at home proved beyond doubt that the owner was the supreme species. One could boast of their prowess as a hunter.

But the fact is most hunters shot tigers and leopards from the safety of a tree-blind, vehicle or elephant back. The cats would be attracted to within gun range by cattle, buffalo or a goat used as bait. For special hunts, hundreds of local villagers were recruited as beaters, trackers and mahouts. To join a shikar (Indian word for the hunt) was the ultimate experience for the adventurous.

The same tiger as above a few moments later

More tigers have been killed for sport in India then anywhere else in the world. In the days of the Raj, it was common to see five, ten or twenty cats lying dead on the ground in front of a hunting party. The Maharajah of Surguja killed some 1,157 tigers during his reign. Some Englishmen claimed to have shot more than 100 tigers. Fortunately in 1972, the Indian government finally banned hunting because the tiger and many other species were threatened with extinction.

The most famous hunter ever to overcome his fear of the big Asian cats was Jim Corbett of India. From 1907 to 1939, he single-handedly dispatched scores of man-eating tigers and leopards. His book ‘Man-eaters of Kumaon’ is a classic. Some cats mentioned in the book had killed hundreds of people. Corbett National Park was established in his honor, and the Indo-Chinese subspecies of tiger Panthera tigris corbetti is named after him.

In Thailand, the tiger and the leopard were also hunted for sport but on a much smaller scale than in India. In the past, rural Thai people living near wilderness areas built houses high off the ground that protected them during the night. But daytime was another thing. If they worked in fields bordering thick jungle or they went into the forest, they risked their lives.

At the turn of the 20th Century as modern firearms, agriculture and transportation took hold in the Kingdom, the forests and wildlife began to disappear. Man-eaters also declined. However, during World War II along the death railway in the Sai Yok district of Kanchanaburi province there were still accounts of man-eating cats. In recent times, there has been no such record. From time to time, domestic cattle are still killed by a tiger or leopard but this is now very rare. Low wildlife densities in the forest and easy prey are the main reason for this occurrence.

Thailand is fortunate in that tiger and leopard plus another seven species of cat still survive in some of the larger national parks and wildlife sanctuaries. Kaeng Krachan National Park is one of those protected areas that still harbor the big cats. Tigers can and do kill the leopard. Although their paths do cross, normally the spotted cat will avoid the striped predator. Documentary accounts and photographs do exist of tigers eating leopards.

In 2002-2003 while carrying out camera trap work in Kaeng Krachan in cooperation with the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department, I was surprised and elated to see both species tripping the same cameras in several areas only days apart. In one month, four different leopards, one of them black, were caught on film. In the following month, a leopard was caught during the day, and a huge male tiger stopped and posed for the camera. Both species were using the same trail for their hunting forays. A few other protected areas like Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai Naresuan wildlife sanctuaries have records of overlapping.

In Kaeng Krachan, an important discovery is that tiger and leopard hunt at all times during the day. It is usually thought they are only active in the late afternoon and throughout the night preferring to rest during the day. More research is required if we are to determine the pattern of daytime hunting by the big cats here. It is probably due to the pristine state of this forest and the lack of human activity.

Without doubt, the future of the big cats depends on one thing only – the complete protection of the remaining forests where they live. If the national parks and wildlife sanctuaries remain intact with a high number of prey species, the big cats will survive. But if overdevelopment and encroachment is allowed to continue, these magnificent animals will eventually disappear.

Unfortunately, too much time and money is wasted by too many organizations talking about saving the tiger and other wildlife, with very little actually being done. Human population growth will eventually destroy most wild places. Only true protection by a few dedicated people will slow the destruction of nature’s precious wildlife and wilderness areas. It is only hoped that the tiger and leopard will continue to survive as they have for millions of years.

Leopard – Panthera pardus

The leopard is closely related to the jaguar of South America. Both have a spotted coat pattern, incidence of melanism (black phase), and relatively short legs. The present distribution of the leopard is restricted to Asia Minor, India, Southeast Asia, the Himalayas, Tibet, China, Siberia, and Africa. Fossils of leopards were found in Pleistocene deposits throughout Europe, the Middle East, Java, and Africa, some 1.5 million years old. These secretive cats are mainly nocturnal. Their populations and ranges are difficult to determine but radio tracking of collared animals has shed new light on their movements and area they live in. ‘Spots’ is more tolerable to humans and their settlements.

Tiger – Panthera tigris

According to fossil evidence Panthera cats branched from the other Felidae about five million years ago in Asia. The first tigers originated in eastern China. Fossils of the earliest tigers date back to the Pleistocene epoch, about 1.6 to two million years ago, have been found in Henan, southeast China, and on the island of Java in Indonesia. The historic range of the tiger covered much of Asia and some of its islands.

However, humans have had an enormous impact on the geographic range of the species. The big cat only survives in 13 countries: Russia, China, India, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Burma, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. The present range is less than five percent of the tiger’s former range. There are less than 5,000 tigers left in the wild.

Elephants : Killing for Cash

THE SAGA OF ‘PANG DURIAN’: An orphaned baby elephant from Phraektakor Reserved Forest in Phetchaburi province close to Kaeng Krachan National Park

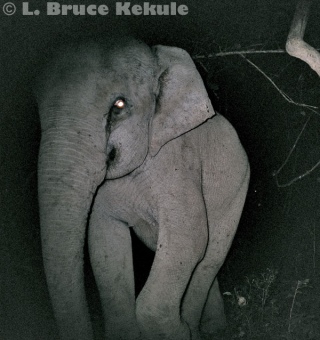

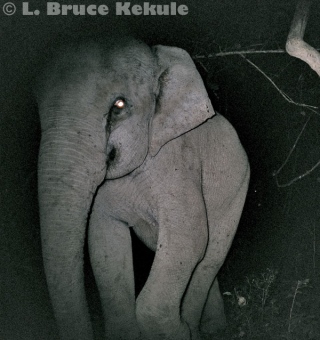

‘Pang Durian’ in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Elephants are being slaughtered in supposedly protected forests so that their young can be used to beg for money on the streets of Bangkok and other cities around the Kingdom. ‘Pang Durian’ is one of those orphaned baby elephants. But unlike other victims of this cruel trade, she has found a new family in the wild. This story is true and based on fact!

‘Pang Durian’ and two step-mothers in Kaeng krachan

A baby elephant wanders aimlessly around her mother lying dead on the ground. The confused young creature has no idea what the future holds as poachers move in to capture her. Her freedom is about to be taken away. Later her spirit will be broken and she will probably end up begging for food and money in some big town or tourist destination

The above scenario is all too common. The killing of mother elephants is perpetrated by some very unscrupulous people who then grab their young and sell them for cash. Other indigenous species like gibbon and langur are hunted down in a similar manner. The middleman and eventual buyers who create the demand for animals snatched from the wild seem to be insulated from the law. When will the killing and kidnapping stop?

Mother and baby tusker camera trapped at a mineral deposit in Kaeng Krachan

The cruelty of this illicit trade is epitomised by the remarkable but traumatic experience of ‘Pang Durian’, a female baby elephant abducted from Phraektakor Reserved Forest, just south of Kaeng Krachan National Park in Phetchaburi province. Her mother was killed by poachers in 1998 and the six-month-old was being kept at Ban Durian, a village just outside the park’s southern boundary. It was there, as she awaited sale on the black market, that she was given her name.

The young orphan was in very poor health. Luckily, however, Royal Forest Department (RFD) rangers in Kaeng Krachan heard about her and investigated. By the time they got to her, she was suffering from a deficiency of protein, calcium and other minerals that would normally come from mother’s milk. Her left leg had become bow shaped and deformed. The villagers hadn’t provided a nutritious, well-balanced diet, and malnutrition had set in.

Elephant family unit in Kaeng Krachan

After negotiations, ‘Pang Durian’ was traded for raw rice, other foodstuffs and construction materials. Shutat Sapphu, head of Ban Krang station in the park, took responsibility and looked after her for several months. Non-governmental organisations including the Wildlife Fund Thailand and Wild Animal Rescue Foundation took an interest in Pang Durian’s plight. After her health began to improve, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF-Thailand) moved her to the well-established Elephant Hospital at Mae Yao Reserve Forest in Lampang. For the next six months, she was in good hands. And her life was about to change for the better. Reintroduction into the wild was the plan.

In 1996, during a state visit to Thailand by Britain’s Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip (then president of the WWF-International), Her Majesty the Queen announced her intention to initiate a reintroduction project for elephants in the Kingdom . The idea was to offer an alternative future to domesticated and traumatised elephants, to let them live out the remainder of their lives as nature had intended.

Family unit camera trapped in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Santuary

In January of 1997, the process officially began when Her Majesty released the first three female elephants ‘Pang Bualoi’, ‘Pang Boonmee’ and ‘Pang Malai’ into Doi Pha Muang Wildlife Sanctuary in Lampang. In February 1998, ‘Pang Sangwan’ and ‘Pang Khamnoi’ were let loose in the same sanctuary as, exactly a year later, were Pang Kammoon and her one-year-old male calf, Plai Song. (“Pang” and “Plai” are Thai prefixes denoting female and male elephants, respectively.)

Some 50 elephants are currently being kept in Lampang for future release and other wilderness areas are now being looked at for inclusion in the project, for which the government recently allocated a budget of 100 million baht. Support for the scheme has come from agencies including the Bureau of the Royal Household, the Thai Elephants Conservation Centre, the Forest Industry Organisation, RFD and WWF.

It was decided to release ‘Pang Durian’ along with four adult elephants (two male, two female) into Kaeng Krachan, the Kingdom’s largest national park. According to the park chief, there are about 200 wild elephants, in seven or eight different herds, living in the interior. The question is, after having become used to humans can elephants be introduced into an area where wild ones roam?

By now ‘Durian’ was more than two years old but she would still be very vulnerable to attack by tigers and leopards and susceptible to possibly recapture by humans. So two stepmothers, ‘Pang Buangern’ (Silver Lotus) and ‘Pang Buathong’ (Golden Lotus), were assigned to look after and protect her. The two males in the group bore the names ‘Plai Eak’ and ‘Plai Mangkorn’ — the latter a bull aged about 60.

Tuskless bull camera trapped on an old logging road in Kaeng Krachan

In late May 2000, the five elephants made the 900-kilometre trip from Lampang south to Phetchaburi; it took about 24 hours to cover the distance. A veterinarian named Dr Somkiat Trongwongsa along with a team of mahouts and RFD rangers working with WWF-Thailand were assigned to look after and monitor the group. One of the females had been fitted with a radio collar for satellite tracking. The group were released near the main entrance at Sam Yot (Three Peaks) Gate into Kaeng Krachan on June 1 of that year.

Sadly, ‘Plai Mangkorn’ was found dead of old age six months later, but the rest of the group continued to move in and out of the park. After the intense rains in late 2000, contact was lost for several months, but in mid-2001 the three surviving adults in the group were spotted near Sam Yot Gate. But Durian had disappeared and everyone feared the worst. Had she been taken by a tiger or lost in the thick jungle?

A tusker camera trapped by the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan

The three adults hung around the gate, refusing to go back into the park. It transpired that they had been chased away from several villages in the vicinity and were becoming a serious problem for the RFD. Eventually, almost a year after their release, it was decided that they should be sent back to Lampang.

In September 2002, while working with the RFD in Kaeng Krachan in conjunction with WWF-Thailand, I made a trip into the park to set up some infra-red camera-traps at mineral licks about 12 kilometres from Sam Yot Gate. The cameras were attached to trees on trails leading to the salt licks and left for one month.

‘Pang Durian’ camera trapped in Kaeng Krachan showing her bowed left front leg

Positive proof that she was surviving with a wild herd in the park

When the films were processed in October, low and behold, ‘Pang Durian’ was spotted passing one of the cameras at about 4 o’clock one morning, her deformed left leg clearly visible. It almost seemed as if she was saying, “Here I am!” Other elephants captured on the same roll of film around the same time meant that this remarkable little elephant was now obviously in good hands. She had come full circle and had been adopted by a herd. A magnificent testimony to the tenacity of Thai elephants and a wonderful Walt Disney ending to the whole scenario.

Actually, RFD rangers had told me earlier that they’d spotted ‘Durian’ one night near Ban Krang station. But this camera trap photo confirmed her continued existence in the park and the partial success of a difficult yet ultimately rewarding reintroduction program. According to Dr Somkiat, the Durian success story indicates that it will only be feasible to reintroduce young elephants, about five years old, into wild populations. A year later, I believe I caught her again on a camera trap but it was more difficult to identify her so I’m not sure if it was her or not. Someday I will find this photograph and re-evaluate it.

Tuskless bull in a mineral deposit in Kaeng Krachan

Countless conflicts have arisen between villagers and the real owners of the land; the creatures whose ancestors have lived there for thousands of years. Many elephants have been persecuted and killed by poisoning, gunshot wounds and electrocution (electric fences carrying an alternating current of 220 volts are used). Fireworks are set off to chase them out of mango orchards and pineapple plantations. But this tactic only frightens them temporarily; the elephants get bolder. Some have gone on the rampage tearing up villagers’ houses, RFD buildings and other facilities.

Wild elephants have also been killed or maimed by vehicles traveling along paved roads in protected areas where there are no speed limits in force. Accidents usually happen at night when the animals are difficult to spot until it is too late.

Young tusker elephant in Khao Ang Rue Nai just before

it was killed by a reckless driver on the road through the sanctuary

Above is a young tusker I camera trapped in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary in Eastern Thailand. Two weeks after, he was hit and killed more than twenty kilometers away by a truck traveling at high speed on the road through the sanctuary. The driver was also killed but his wife next to him survived. The powers-to be have now closed the road from 9pm to 5am to allow animals freedom to use the road during the night. Road kill has dropped more than 50 percent and is considered a success in wildlife conservation and the authorities should be commended for taking action. This young tusker did not die in vain

Probably the most appalling treatment meted out to pachyderms is the beatings baby elephants snatched from the wild have to endure as their captors try to make them toe the line. Most are fed totally unsuitable food that lacks the necessary protein, minerals and vitamins. Later, these youngsters will be forced to ply the hot, dusty polluted streets of Thai towns begging for food and money.

Given the lax legislation concerning domesticated elephants, and poor enforcement, the future for these unfortunate animals is bleak. Continuous calls for change are ignored. Mahouts are still bringing elephants into urban areas and tourist traps. At one time, driving around Bangkok at night and you were almost certain to spot a huge gray beast plodding along with a red light or a CD attached to its tail. Even though this has been stopped by the BMA city officials, it still goes on in other parts of Thailand where there are late-night eateries and tourists.

One can only hope that the ‘Pang Durian’ success story will wake people up to the plight of these noble beasts which has played such an important role in Thai traditions, belief systems, culture, society and politics, and which has been involved in almost every important event in the Kingdom’s history.

Once featured on the Thai flag, the elephant is still a national symbol in which we should take pride. It needs our love and compassion, plus our help and respect. Without that, the magnificent Asian elephant is doomed.

Heavy storms and floods have closed the visitors’ road, and wildlife has thrived because rangers kept it closed

First published in October 2003

Just a three-hour drive southwest of Bangkok, along Phetchaburi province’s border with Burma, lies Kaeng Krachan – Thailand’s largest national park, encompassing 2,915 square kilometers of mostly tropical broad-leafed evergreen and mixed deciduous forests. In the interior live tigers, leopards, elephants, gaur, tapir and many other amazing species. Even the rare Siamese crocodile still lurks in one of the park’s watercourses. Kaeng Krachan is one of the country’s least touched forests.

Black Leopard phase

Prior to the government ban in 1989, logging was carried out in the lowland areas of Kaeng Krachan. Timber cutters cut an 18km road into the interior from Sam Yot Mountain to transport logs from the concession areas. When logging ceased, the Royal Forest Department extended the road another 18km to Phanern Thung Mountain to facilitate visitors to Thor Thip Waterfall.

Kaeng Krachan became a popular destination, with thousands of visitors each year. But too many visitors ruined some areas in the park. Wild creatures, especially mammals, faded into the more inaccessible areas and were not often seen along the road.

In October of 2002, two back-to-back violent tropical rainstorms hit Kaeng Krachan, overflowing the park’s streams and rivers, and inundating much of Phetchaburi province. Five local villagers, along with homes, vehicles, and livestock, were swept away in the worst flooding in more than 40 years. Blame for the flash floods was placed on excessive logging of the past.

Road washed out

There was extensive devastation inside the park as well. Floods washed away many sections of the main road, and more than 50 landslides uprooted trees and blocked access by tourists. The National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department (DNP) has to wait for funds to repair the road, and this takes time. That ended the flow of people in their noisy vehicles, and the wild creatures began to use the road in their search for food and water.

Yellow phase leopard in the interior

For the last few years I have worked with the RFD and later the DNP, to carry out infrared camera-trap surveys in Kaeng Krachan to monitor large and small mammals. Some exciting photographs have resulted. Tigers and leopards, both in black and yellow phases, have come into almost every camera trap. The big cats are also surviving in overlapping territories in quite a few areas, especially along the Phetchaburi River, and along the road close to the ranger station on Phanern Thung Mountain.

Indochinese Tiger camera-trapped

Last January, more than three months after the storms closed the road, was a great opportunity to camera-trap. Four camera-trap units were placed at Kilometres 31, 32, 33 and 35, and the units started photographing almost immediately.

Tigers and leopards were now using the road to hunt day and night, and creatures like the very rare Fea’s muntjac were also caught on film. Other animals such as Asian wild dogs, black bears, large Indian civets, leopard cats, common muntjac and porcupines were also camera-trapped.

Fea's muntjac camera-trapped

One of Kaeng Krachan’s biggest advantages (from the animals’ viewpoint) is that the rainy season makes its interior inaccessible. It is almost impossible to move in and out of the main Phetchaburi watershed area when the river is swollen by heavy rains, meaning from June to October. At present, the river is a raging torrent and only professional rope handlers could possibly hope to cross. And this doesn’t mention the leeches, which are everywhere.

Without human interference, the wildlife of Kaeng Krachan lives in total peace. The ecosystem rejuvenates itself.

An example: The staff at the national park headquarters decided to close an old logging road about 12km from the main gate at Sam Yot, securing it with a steel pipe barrier. No vehicles were allowed to enter this 9km road, which leads to important Huai Mae Sariang watershed. After about a month, I set 10 cameras along the road and nearby mineral licks. Tigers, leopards, elephants, gaur, sambar, serow, common muntjac, civet cats and porcupines made an appearance.

At one camera, four different leopards, three in yellow phase and one in the black phase, were camera-trapped. The next month, a mature leopard was caught at midday, and after that, a huge male tiger (shown in the main photograph) was captured on film. The road is now used mainly by wild creatures and forest rangers on patrol and in many places, the forest on either side has grown together.

The DNP should be commended for cleaning up the park while the road was closed. At Ban Krang ranger station alone, they collected hundreds of rubbish bags full of trash thrown into the bush by visitors.

The department has also set new regulations for visitors. Other than the headquarters area down the mountains, camping is allowed only at Ban Krang. Only day trips to Phanern Thung and Thor Thip waterfalls are allowed, and a forest ranger must accompany the visitors.

Without doubt, these measures will help Kaeng Krachan’s natural ecosystem. Due to the recent heavy rains, the park is closed once again until the beginning of the dry season next month.

These camera-trap programs have barely scratched the surface of the park’s full potential. There are still many species that surely survive in the interior. Further research and surveys should be carried out by the department to determine the diversity of this great forest.

Photo captions: The tiger, the leopard and the Fea’s muntjac are just a few examples of predators and prey that venture out on the park’s road while it is closed to tourists. Since last year, violent storms have torn up many sections of Kaeng Krachan’s main road, cutting human access to the forest’s interior.

Kaeng Krachan: Jewel in the Tenasserim Range

One of the Kingdom’s Last Great Tiger Reserves: Thailand’s Largest National Park and Biodiversity Hotspot

Just a short forty years ago, a local Karen hunter sitting alone in a tree-stand made of bamboo waits by the headwaters of the Phetchaburi River. He has trekked south from his humble abode for about a week. This young man is a traditional hunter and knows how to subsist by himself in this forbidding forest. His father before him also hunted this place and taught him all the tricks-of-the-trade: hunting for a living and surviving in the wild.

Rainbow over the Phetchaburi River

Darkness envelopes the man as the sun sets behind him. The moon and stars are brilliant and night visibility is good. The location is a mineral deposit (salt lick) deep in the interior close to the river. This site attracts gaur, banteng, elephant, and the extremely rare Sumatran rhino, plus sambar, muntjac and wild pigs. Tigers and leopards also came looking for prey. It was a magnificent animal kingdom.

Serow camera trapped on old logging road

His primary target was the rhino but would take anything that came to the natural seep for the life-giving minerals. The hunter sets in for the night knowing the large mammals sometimes prefer to visit in darkness. He is armed with a crude self-made muzzle-loading rifle. It is the dry season, and he is not too worried about a misfire. The caliber is as large as his thumb, and the round heavy lead ball and black powder charge is enough to take down an elephant.

A great hornbill lifting off a fruit tree

At last, a dark shape emerges from the forest and slowly ambles straight to the seep. Head down, the odd-toed ungulate drinks to quench its thirst. The hunter switches on his flashlight and temporarily blinds the two-horned rhinoceros. He takes aim and fires his weapon with a resounding boom and tremendous muzzle flash that breaks the still night. The creature is hit in the shoulder and runs for a short distance before collapsing. It is a long wait but dawn eventually comes and the hunter climbs down from the platform to investigate his trophy. Sadly, he just killed one of the last few Sumatran rhinos left in this forest.

Indochinese tiger caught by camera trap by the Phetchaburi River

Shortly hereafter, he dispatched another rhino and then never saw the species again. He sold the horns, which were small, for about 100 U.S. dollars to a waiting middleman: a pathetic return compared to what the horns probably fetched on the black market which was most likely in the thousands of dollars. This voracious wildlife trade has absolutely wiped out many species from the forests throughout the Kingdom. It has been devastating and unfortunately, still carries on to this day.

Indochinese tiger camera trapped at a mineral lick

When Kaeng Krachan was declared a national park in 1981, the hunter, his family and several other families in the little village were relocated more than twenty kilometers outside the boundaries of the protected area. A plot of land was given to them but it was not to much, probably just sustainable. He was told that he could not hunt anymore and had to eke out a living by farming. It was a difficult road ahead for them after living in the forests since they were born. Relocation was tough but they adapted and survived. The hunter and his family now plant pineapples and other crops. He stopped hunting, and his two sons actually care about conserving the forest and wildlife.

Bull elephant camera trapped at a mineral deposit

The Phetchaburi is one of Thailand’s most famous waterways. King Rama V visited this waterway and His Majesty had water sent to his palace in Bangkok for drinking purposes. The King was also presented with rare white elephants found here. During his reign, both Sumatran and Javan rhinos existed in the interior in good numbers.

Tiger camera trapped by the Phetchaburi River

In 1914-1915, an Englishman named K.G. Gairdner made many forays into the Phetchaburi watershed recording the wildlife. He published several papers in the Natural History Society of Siam about his exploits and encounters in this wilderness. Large herds of elephants and gaur were present and many tigers thrived due to the prolific amount of prey species.

Tiger camera trapped by the Phetchaburi River

The Phetchaburi River flows from the Tenasserim Range through Kaeng Krachan, the Kingdom’s largest national park encompassing 2,915 square kilometers (1,125 square miles). It is still pristine within some areas of the park. Montane forest is found on the highest peaks with predominantly dry evergreen forest interspersed with mixed deciduous vegetation. Even though both species of rhino have disappeared, the park continues to showcase a great diversity of wildlife.

Gaur camera trapped at a mineral lick

Rare and endangered animals still survive such as the Siamese crocodile and stumped-tailed macaque as well as elephant, gaur, tiger, leopard, Asian wild dog, tapir, sun bear and Asiatic black bear. Other mammals such as sambar, and the rare Fea’s muntjac plus common muntjac and wild pig keep the balance of nature intact by providing ample prey for the carnivores. Banteng were common in the mixed deciduous lowlands but humans encroaching on the forest soon eliminated most of these wild cattle and there are very few remaining if any at all.

Gaur herd spooked by camera trap

However, the Phetchaburi is still an important watershed and is the main source of water for people on the lowlands. Hornbills and gibbons are plentiful. I once listened to four separate gibbon groups calling at the same time from Phanern Thung Mountain. The surrounding forest contains fertile food in abundance and safe habitats for all the wild animals. Both Sundaic and Indo-Chinese species survive here.

Gaur cow camera trapped at a mineral deposit

The Phetchaburi is one of the Kingdom’s least disturbed waterways and although the lower section is dammed, the upper reaches of the river are still fairly intact. More than 400 bird species have been recorded in Kaeng Krachan and thousands of unusual plant and insect species can be found. There are more than 70 species of fish in the waterway. Many reptiles including the king cobra and reticulated python, and amphibians like the giant tree frog are here. There are probably some species new to science still to be discovered, specially insects and plants.

Additional animals found in Kaeng Krachan National Park:

Siamese crocodile in the Phetchaburi River

Lone Siamese croc in the river

Smooth-coated otters camera-trapped by the Phetcahburi River

Water monitor hunting for prey by the Phetchaburi River

Smooth-coated otter hunting by the Phetchaburi River

Smooth-coated otter jumping into the Phetchaburi River

Lesser fish-eagle by the Phetchaburi River

Lesser fish-eagle chick in a nest above the Phetcahburi River

Crocodile pond in the Phetchaburi River