THIS POST IS THE FOURTH IN A SERIES OF WILDLIFE STORIES THAT WERE PUBLISHED IN THE BANGKOK POST. Text and photos © L. Bruce Kekule

A sanctuary of beauty: Thailand’s top protected area in the central-west

Wild water buffalo herd in Huai Kha Khaeng

Mist hangs in the air early one morning as a green peafowl calls from up-river. A male bird, its long tail feathers glistening in the early sun, struts across a sandbar looking for something to eat. A pair of wreathed hornbills fly into a fruiting fig tree and two white-winged ducks honk as they wing past Khao Ban Dai ranger station deep in the interior of Thailand’s top protected area.

Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, which covers some 2,780 square kilometers (1,073 square miles) of mountainous forest in Uthai Thani province in the western central plains, is one of the greatest biospheres on the planet. Its status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site is well deserved. The river named Huai Kha Khaeng flows through the middle of the sanctuary for about 100 kilometers before joining the Khwae Yai River further south. This riverine habitat has an unmatched biodiversity with many tributary streams that course through hilly woodland. Thousands of plants and animals thrive here, and the sanctuary is truly a tribute to the Kingdom’s natural heritage.

Tuskless bull elephant at a mineral deposit

Deciduous and hill evergreen forest make up most of this forest. Thousands of insect species thrive and the bird life is exceptional. There are an incredible 22 woodpecker species including the white-bellied and great slaty, the largest of the “Old World” woodpeckers – one of the highest densities in the world for comparable areas. Hornbills and fish-eagles are also found along the river, and all up there are more than 350 recorded bird species.

Banteng cows at a waterhole

Thailand’s largest bird, the green peafowl is now rare and found only in a few locations in the Kingdom. It is the most spectacular of all Thai birds, especially in November when the breeding season begins. The magnificent tail feather display when the male walks along the river is really something to see. The call of a male peafowl is truly inspirational, and its feathers a beautiful translucent green color. These birds still thrive in the deciduous and bamboo thickets along the river and in the interior, and this sanctuary has the one of the last and largest wild concentration of this species in the world.

Banteng bull by Huai Mae Dee, a tributary of Huai Kha Khaeng

Mammals from elephants to treeshrews survive in good numbers in most areas of the sanctuary. Due to an incredible amount of prey animals like deer, wild pig and cattle, the tiger, leopard and Asian wild dog thrive in good numbers too. There are eight species of cat from the tiger down to the little leopard cat, plus another eight species of civet. Three species of wild bovid including gaur, banteng and wild water buffalo are here, probably the only place in the world where this occurs.

Banteng herd including a big bull, cows and calves

Probably, the most significant species in the protected area is the buffalo. This is the last wild herd in the Kingdom, and Southeast Asia for that matter. Centuries ago, wild water buffalo were found in many forests and rivers. A mature bull can weigh up to a ton and have hooves eight inches (20cm) across. They leave deep tracks in the sandy soil along the river. These magnificent bovid are much larger and more aggressive than their domestic counterparts. Wild buffalo have a distinct forehead with horn bases closer together than domestic buffalo, whose boss is wider. Wild buffalo have a fierce temperament and will group together in the herd to face a predator like a tiger or Asian wild dog. Male solitary bulls will charge without hesitation. Many a hunter has had a close call or been killed by these massive low-slung beasts.

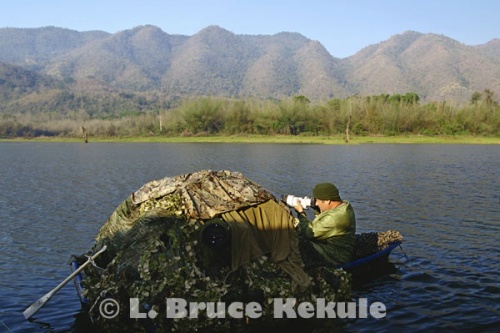

Wild water buffalo cow charging my boat-blind

Due to a very small population of just 50 or so individuals, the future of the wild water buffalo in Thailand is uncertain. Many dangers threaten them, such as foot and mouth disease, which could easily be passed on by domesticated buffalo living just outside the southern border of the sanctuary. In the past, local villagers have deliberately mingled their buffalo with the wild herd so that the offspring would be sturdy. Also, a few solitary bulls have come out of the sanctuary looking for females in heat. This is a very dangerous situation, which if not checked, could lead to a decline of all the classic herbivores in Huai Kha Khaeng. The southern border at Krueng Krai ranger station remains a gateway for danger and must be protected at all costs.

Black leopard in the afternoon sun showing its spots

Carnivores such as tiger and leopard are common in the interior, as are the herbivores. The balance of nature is played out everyday where “eat or be eaten” is the norm. Vultures were once found here but have virtually disappeared from Thailand’s skies primarily due to people poisoning carcasses. Illegal poaching, logging and gathering of forest products still occurs on a small scale and is a constant drain on all the species of flora and fauna.

Indochinese tiger at a waterhole deep in the interior

Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary is part of the ‘Western Forest Complex’, the largest forested area in Southeast Asia, which covers some 15,000 square kilometers (5800 sq. miles). All the protected areas are the responsibility of the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation. Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary to the west is also a World Heritage Site and forms a continuous forest with Huai Kha Khaeng.

Seub Nakhasathien – Thailand’s hero of wildlife conservation

There are many heroes of the past but one-man – Seub Nakhasathien – stands out. Seub gave his life for Huai Kha Khaeng and the nature conservation movement. In September 1990, this dedicated ranger, who fought hard for the rights of wild flora and fauna, took his own life at the headquarters area. A large bronze statue has been built close to his house in his honor, and is now his spiritual home. Many people flock to this magic place, including myself, to pay homage to him.

Oriental darter drying its wings in the morning sun

Seub helped to propose Huai Kha Khaeng as a World Heritage Site, along with Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary to the west. But he did not live long enough to see the proposal accepted. Together, the two sanctuaries help protect 6,427 square kilometers (2,481 square miles) of pristine wildlife habitat. They make up one of the finest and largest protected areas in Southeast Asia. The flora and fauna of this area includes an exceptional number of species from four bio-geographic zones – Sino-Himalayan, Sundaic, Indo-Burmese and Indo-Chinese, with significant habitat diversity.

The author in an old boat-blind after wild water buffalo

Four or five years ago, the department built a huge visitor center and three VIP bungalows at Khao Ban Dai. More than one hundred construction workers camped out here and materials were trucked into the location. Construction took more than a year. During and just after the completion of these buildings, I made many trips to the station only to find out that green peafowl and many other creatures normally seen had disappeared, or it seemed that way. Last month, I made a trip to Khao Ban Dai and it was an inspiration to see that green peafowl, wreathed hornbills, fish-eagles, banteng, gaur have returned to this magnificent natural paradise. It means, increase protection and patrols by the DNP are really working over the long run.

However, the importance of saving Huai Kha Khaeng for future generations cannot be stressed enough. It is hoped that management of the protected area will continue to improve, and government funding will also increase. More personnel are needed to take care of these valuable places. As it stands, budgets have been consistently slashed across the board for all protected areas over the last few years by bean counters. The department’s old policies need to be improved, and a constant watch kept for corruption – it can be tough to prevent. Only time will tell if Huai Kha Khaeng can survive such threats.

NOTES FROM THE FIELD:

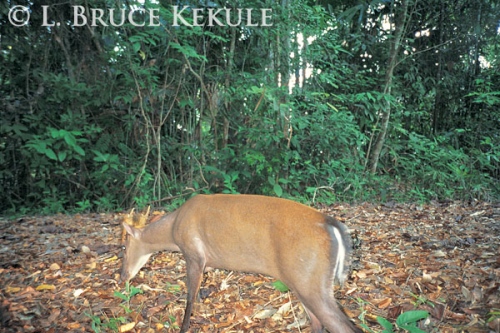

In December 2008 when the first cold snap arrives, I was fortunate to visit Huai Kha Khaeng for a week or so. The dry season had begun and dead leaves carpeted the forest floor. Along Huai Mae Dee, the largest tributary of Huai Kha Khaeng, several wildlife-viewing platforms have been erected allowing rangers and researchers to do surveys, and wildlife photographers a chance to photograph the magnificent wildlife thriving here including elephant, banteng, gaur, sambar, muntjac, and very occasionally a tiger or leopard. Other creatures like macaque monkeys, green peafowl, yellow-throated martin and many other smaller animals are also seen here.

Tuskless bull elephant in the afternoon sun

On the morning of Christmas Eve, I awoke early, ate breakfast and drove some 8 kilometers to the trail leading down to the photo-blind. As I walked down the trail about 6am, I came upon a large pile of fresh elephant dung that had just been deposited. A large solitary bull elephant was close by. I hesitated, but carried on feeling lucky that I would not bump into him. I reached the blind and began climbing up the ladder when a rung gave way and I fell through. When the smoke cleared, I had broken two ribs. I then picked up my cameras and other equipment and managed to climb up crossing over where the third rung had been.

I then settled in the blind with my cameras facing across the river at the mineral deposit (commonly called salt lick). Many creatures come to these natural seeps for the life giving minerals. After waiting all day in pain, at about 4:30pm, a large tusk-less bull elephant stepped out of the forest in beautiful afternoon light and crossed the river just 20 meters from where I was. He then headed down river and I gave out a sigh of relief. Loners like this old boy (estimated about 40 years old) are sometimes very aggressive to anything it senses as a threat. It has become difficult to get good photographs due to their elusive nature. Our paths crossed very briefly and I feel privileged to have seen and photographed this magnificent wild elephant.

New addition to the above that was not published with the original story due to space in the newspaper…Update: 18 July, 2017….!

However, I was not doing too good. I had to leave all my stuff as I could not carry anything back for an hour’s walk to the truck with the worrisome rib bones that hurt like hell.

The next day, I tried to sit in another blind closer to the road but that was really tough. I finally got back to my truck and drove to Bangkok where I was omitted to the hospital with two broken ribs. It put me out of action for quite awhile as it is tough moving around with said ribs and one must strap-up with large belly-band belts, all day and all night for quite a while (over one year for me) to heal…it was a very slow process and after two years, I feel OK…but every once in awhile, I get a twinge in the small of my back where the break took place……!

Published in the Bangkok Post’s Outlook Section on April 27, 2009. Most of the photos shown above were actually used in the newspaper article when it was published.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook