WILDLIFE in THAILAND: A Photographic Portfolio of Thailand’s Natural Heritage – Part One

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

“In my opinion, we should not sit around and argue about the way we use the forest because very little remains“

Seub Nakhasathien

FRONT JACKET

Gaur Bos gaurus in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. This magnificent solitary bull, estimated age about 12 years, has worn his horns down at the tips and damaged the bases by years of fighting with other bulls. Truly in his prime, he has survived danger all his life.

Back Jacket

Leopard Panthera pardus late one afternoon, just before disappearing into the forest. The author, from his vantage point in a photo blind up in a tree, hears langur monkey and barking deer call out as the cat passes by. Very few photographs of black leopard, also known as black panther, have been taken in the wild of Thailand.

Inside Jacket

About this book:

As one millennium passes and another begins, the world has lost much of its rain forests and their inhabitants in the destructive movement of progress. Human population growth, industrialization and man’s quest for money and power are the main culprits.

Recent surveys tell us that an area of tropical forest the size of New York’s Park is being destroyed every ten minutes, the size of New Orleans every month and that of the British Isles every year. Forests are being cut down for timber, livestock ranches, farms, food and housing. Wherever this devastation takes place, it contributes to climatic change through greater greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. In recent times, severe world weather conditions caused by the El Nino and La Nina phenomena, destructive typhoons, hurricanes, cyclones and their disastrous effects of drought and floods, plus earthquakes have wreaked havoc globally.

We are thus faced with an intractable dilemma. The destruction of our flora and fauna by this and previous generations will have severe consequences in the new millennium, affecting the weather, land and lives of people all over the country and the world.

At the end of the World War II, Thailand’s forests covered an estimated 75-percent of the country. Now, perhaps only 20-percent of forest cover remains, of which half to three-quarters is in protected areas. Many species of plant and animal life have already become extinct to be seen now only in text books, drawings and old photographs.

We are at a crossroads where education and a sense of awareness for all natural living things are the most important tools to save what is left of our forests and wildlife. We also need to communicate through photographic books like this one, and the news media, to those who are uneducated about wildlife so they may understand and see the beauty of the natural world.

Enjoy this photographic trip into the wild of Thailand. Put yourself into each photo as if you were actually there and see the magnificent wildlife that still survives in the Kingdom. This book makes a powerful statement; the photographs speak for themselves.

Wildlife in the Kingdom of Wildlife offers a photographic portfolio of the wildlife in this country, a journey into the realm of the natural world with camera and film to record a small part of what was once a great wilderness.

In order to collect as many images as possible in the four-year period this book allowed, some of the best national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and non-hunting areas were chosen as photographic sites. By learning about each area from continued visits, a considerable knowledge was gained of wildlife habits and habitats. This determined the best times and places for 100 percent photographic success. Wildlife is so wary of humans that it is extremely difficult to see or photograph them in their natural habitat.

Thailand’s flora and fauna are some of the world’s most beautiful. We all need to join together to save what little is left, not only for ourselves but for our children. Taking the inspiration given to us by His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej, Her Majesty Queen Sirikit and the Royal Family, whose proactive concern for the environment continues unabated, may we all play our part in saving and protecting the magnificent wildlife in the Kingdom of Thailand.

Lawrence Bruce Kekule, an American by birth, has lived in Thailand since 1964. Immediately upon arrival, aged 19, he went up to Chiang Mai to work in his father’s wood handicraft business. His lifelong love of being in the forest continues and, whenever he has the opportunity, ventures into the wild with his cameras. His dream to produce a pictorial book of Thailand’s wildlife began during the mid-1980s after he witnessed extreme changes to the country’s wild areas. Then, in 1995, with his trusty Nikon cameras, he started to visit as many protected conservation areas as possible in search of wildlife subjects to record on film. Wildlife in the Kingdom of Thailand is the fulfillment of his dream.

Page 2-3

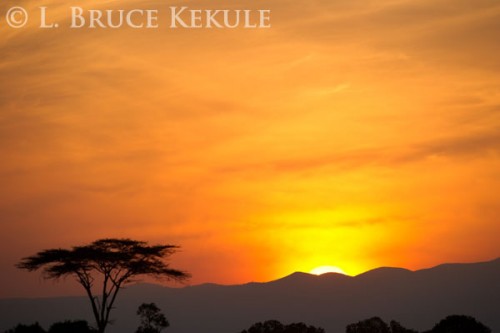

Sunset in Sai Yok National Park in Western Thailand along the Kwae Noi River. This beautiful protected area has some very rare creatures including tiger, leopard, wild elephant, gaur and many other large and small mammals. The ‘Bridge on the River Kwae’ is not far from here and was made famous during WW II and the Japanese occupation in the 1940s.

Page 4-5

Asian Tapir Tapirus indicus in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary.There are many scars on the flank of this otherwise handsome animal (top), probably caused by a predator. Tapir have very thick skin that protects them from attack. Their colouring would seem to stand out, but in fact they are quite well camouflaged. The two-tone colouring breaks up its outline at night and in dark evergreen forests during the day. They are very quick while moving through the brush when escaping from a predator. This very rare mammal, still found in the sanctuary, is nocturnal and rarely seen in daylight. There are very few left here. It is hoped that they will continue to survive in this World Heritage Site.

CREDITS

Page 6

PUBLISHED in 1999 by WKT Publishing Co., Ltd 102/32 Soi Ronnachai

Setsiri Road, Phayathai Bangkok 10400, Thailand Tel: (66-2) 619-6774

Fax: (66-2) 619-6775 e-mail: lbkekule@mac.com

DISTRIBUTED in Thailand by Asia Books Co., Ltd 5 Sukhumvit Road Soi 61

Bangkok 10110, Thailand P.O.Box 40Tel: (66-2) 714-0740-2 ext. 221-223

Fax: (66-2) 381-1621, 391-2277 e-mail: asiabook@ksc.th.com

Photographs and text: Copyright © 1999 L. Bruce Kekule

Map: © 1999 David Unkovich

Editors: Keith Hardy, Tim Sharp

Technical Editors: Dr Sompoad Srikosamatara, Patrick Baker, Lon Grassman Jr.

L. Bruce Kekule would like to thank the companies and organizations whose sponsorship has made this book possible.

Paper Supplied: Advance Agro Public Co., Ltd, Bangkok, Thailand

Printed and bound: Sirivatana Interprint Public Co., Ltd Bangkok, Thailand

Re-Design and Desktop Publishing: L. Bruce Kekule WKT Publishing

Camera Technical Support: George Poole, Waranun Chutchawantipakorn and Sunthorn Teeratamtada

Film Processing: Green House Photo Lab, Bangkok, Thailand

FIRST EDITION – 1999, SECOND PRINTING – 2000, SECOND EDITION – 2001

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,without prior permission of L. Bruce Kekule, WKT Publishing Co., Ltd, Bangkok, Thailand.

For information about reproduction contact WKT Publishing Co., Ltd

Endorsed by the Royal Forest Department

ISBN — 974-87099-8-1

Page 7

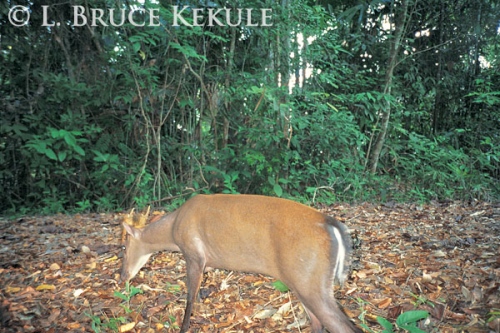

Common Barking Deer Muntiacus muntjak in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. This mature male with antlers in velvet, photographed on the same day as the old bull gaur on the front cover, is after a doe in heat. Some other photographs in this book, such as those of banteng, green peafowl and wild dog, were also taken at this remarkable mineral lick.

Page 8

Green Peafowl Pavo muticus at a mineral lick in Huai Kha Khaeng that is also used by elephant, gaur, banteng, barking deer, wild pig, crab-eating mongoose and monitor lizard. Other birds here include the vernal hanging parrot, red-breasted parakeet, thick-billed pigeon and mountain imperial pigeon, changeable hawk-eagle and hornbill.

CONTENTS

Page 9

Foreword – 11

Introduction – 12

Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary – 18

Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary – 74

Khao Yai National Park – 100

Kaeng Krachan National Park – 112

Sai Yok National Park – 120

Mountains of the North – 132

Beung Boraphet Non-hunting Area – 142

Wildlife Research – 156

Zoos and captive breeding stations – 162

The Dark Side of Nature – 170

Wildlife photography – 174

Map and List of protected Areas – 176

Acknowledgments – 177

Sponsor Profiles – 178

Bibliography – 180

Photographic index – 181

================================================================

Page 10-11

Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary during the dry season when the river is at its lowest level. Many species thrive here including tiger, leopard, elephant, wild water buffalo, banteng, gaur and many other large mammals plus smaller creatures. It is the greatest wildlife sanctuary in Thailand.

FOREWORD

Dr Plodprasop Suraswadi – Director General of the Royal Forest Department

Wildlife in the Kingdom of Thailand is a photographic journey into the realm of nature, conveying to the world the magnificent beauty and diversity of Thailand’s natural heritage. Its purpose is to inspire increased conservation awareness in the minds of this generation, in both local and international communities. The extremely difficult but important need to protect and save Thailand’s surviving forests and wildlife is one of the Kingdom’s top priorities. Indeed, His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej, during his continuing reign of more than 50 years, has been and remains at the forefront of many wildlife conservation and reforestation projects around the country.

Wildlife photography is one of the toughest tests of a photographer and this book contains some truly remarkable photographs of rare and endangered wildlife in their natural habitats. There are photographs here of elephant, gaur, banteng, wild water buffalo, tiger, leopard and many other wonderful creatures of nature. Most of these animals are seldom seen let alone photographed. For his outstanding work in putting this book together, both in text and photographs, L. Bruce Kekule is to be commended. The Kingdom will truly benefit from his excellent portrayal of its wildlife.

Over millions of years, the evolution of our flora and fauna has created an abundance that is truly astonishing, and we are all responsible for its continued survival. Enjoy this photographic portfolio of Thailand’s natural world, but never forget this book’s urgent message: Nature’s clock is ticking relentlessly as species after species disappears from the land. Only prompt action can halt this continuing tragedy and we should all work together to fight the man-made perils facing nature. Then, and only then, can we safely say that the children of today and tomorrow will enjoy the Kingdom’s natural heritage far into the new millennium. Finally, we must all learn to love, respect and live in harmonious coexistence with the wonderful world of nature.

INTRODUCTION: Thailand’s Natural Heritage

Page 12

Cycad Cycas pectinata in Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary. The cycad is considered one of the oldest species of plant in Thailand, having been around since at least the days of the dinosaur some 120 million years ago. The plant at the back has died, hence the golden color of its fronds. Cycad are still common in the sanctuary and along the Tenasserim and Thanon Thongchai mountain ranges.

The Kingdom’s glorious wildlife

About 120 million years ago, one of the most gigantic carnivorous dinosaur the world has ever known, roamed in what is now part of northeast Thailand. Just recently discovered and named, this tyrannosaur Siamotyrannus isanensis, the predecessor of the famed North American Tyrannosaurus rex, adds to the sum total of knowledge that this mystic and majestic land has always been a haven for some extremely interesting and diversified wildlife.

Thailand is one of the wealthiest countries in the world in terms of biodiversity. As just one example, Doi Suthep-Pui National Park, an area of only 261 square kilometers, near the city of Chiang Mai, contains more species of plant than the whole of Europe. The country was once so rich in flora and fauna that a movie named ‘Chang’ (Thai word for elephant) was made in Nan province in the 1920s, using real wildlife and the jungle as props. This movie was recently rediscovered in the West and shown on national television.

Thailand owes its extraordinary natural wealth to its location at the heart of Southeast Asia. With an area of 513,115 square kilometers, it is at the crossroads of several major bioregions and covers almost 15 degrees of latitude in the tropics. These conditions, together with the country’s vast range of land- forms, weather patterns, vegetation types that derive from its geographic location, generate this astonishing natural wealth.

Some idea of this richness can be gained by looking through this book. Tragically, much of what you will see is now seriously endangered. As recently as the beginning of the twentieth century the whole of the country, from the mountains of the north to the coastlines and islands of the south, and from the eastern plateaus across the central plains to the thick jungles of the west, was covered by a lush green carpet of forest that teemed with life. Today, this once vast natural domain is now sadly depleted.

Consider, for instance, the world’s smallest mammal, the Kitti’s hog-nosed bat, named after its discoverer. This bat was found in the 1970s within a few caves along the western border with Myanmar (formally known as Burma) in Sai Yok National Park. Although it still survives, it is endangered throughout its range. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists this bat among the most endangered animals in the world.

The Asian elephant is the second largest land mammal on earth, surpassed in size only by its African cousin. Elephant live here in the wild, and in the cities and towns where many of them are abused and exploited for the tourist trade and open-air restaurants. Their numbers in the wild diminish year by year due to habitat loss that basically affects all wildlife. Some are hunted for their ivory but there are very few big tuskers left. Probably no more than 5,000 wild and domesticated elephant remain in Thailand, a sad situation indeed.

Page 13

Bengal Monitor Varanus bengalensis in Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary. This female lizard is full of eggs, ready to lay. When the author’s presence was detected, she dashed full tilt across the mineral lick. These carnivorous reptiles are still common in Thailand.

Thailand has gaur — the great forest ox and world’s largest bovine. There are also banteng, a slightly smaller species of red cattle, in some areas. Asian wild water buffalo, akin to domesticated buffalo, also exist here but in very small numbers and found only in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. Only one herd remains, comprising less than 50 animals. Other wild herds still exist in India and Nepal. Prior to the long Indochina conflict, Vietnam and Cambodia also had wild water buffalo but their status today is not known. All wild bovine in this region are seriously endangered.

The world’s largest cat, the tiger, is here, albeit critically endangered throughout its range. Other cats include Asian leopard (black and spotted), golden cat, clouded leopard and marbled cat, along with several other smaller species of feline. There are two species of Canidae, Asian wild dog and Asiatic jackal. They are all in serious jeopardy due to poaching of their prey species and habitat loss.

There are five species of deer in Thailand comprising of sambar (the largest), hog deer, brow-antlered (Eld’s) deer, common barking deer and Fea’s barking deer. There are two species of mouse deer (greater and lesser). Hog deer have been reintroduced into Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary and brow-antlered deer were reintroduced into Huai Kha Khaeng and doing well.

Other ungulates (hoofed animals) are tapir, wild pig and two species of goat-antelope, the serow and goral. Goral live in several small pockets in Om Koi and Maelao-Maesae wildlife sanctuaries and a few other areas in the north, where their existence is under threat from poachers. They are therefore extremely endangered. There are a few unconfirmed reports of Sumatran rhinoceros along the western border with Myanmar and southern border with Malaysia. They have not been sighted officially for more than 30 years.

Asiatic black bear and Malaysian sun bear can be found in a few forested areas but are highly endangered by the illegal market for bear paws and bladders. Seven species of civet cat, including the binturong and large Indian civet, as well as many other mammals like badger, weasel, pangolin, porcupine, mongoose, marten, otter, bat, squirrel and other rodents are found here. Primates include slow loris, gibbon, macaque and langur.

Thailand also has a fascinating array of birdlife. Over 1060 species have been recorded (ten per cent of the world’s birds!), with new ones added to the list all the time. During the winter months, thousands of birds migrate to Thailand and some pass through on their way even further south. Unfortunately, many species of flora and fauna have disappeared from the land due to poaching and severe encroachment on their habitat.

Insect species number in the hundreds of thousands. In Huai Kha Khaeng alone, thousands of beetle species have been found in one hectare. Many species continue to be discovered.

A coastline stretching for thousands of kilometers affords an unparalleled marine habitat that includes coastal areas covered with moist evergreen, swamps and mangroves.

Clearly, this book could not hope to record more than a fraction of this wealth. Therefore the author has chosen to concentrate on a select few of the major national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and non-hunting areas. By learning about each area through repeated visits, it has been possible to capture unique moments in the lives of some of this country’s most beautiful wildlife.

It is important to understand just how severely threatened much of this superb wildlife really is. As recently as the turn of the 20th century, and just north of what is now Bangkok, elephant, tiger, deer and other animals roamed. In the 1920s, Bangkok was still a sleepy riverside town with almost no roads. Even in the 1940s, any journey over 100 kilometers from Bangkok meant travelling very slowly along deeply rutted dirt tracks that were passable only in the dry season.

Although serious deforestation began as long as 100 years ago, it was not until Thailand was caught up in the mad rush of modernization after World War II that its flora and fauna came under attack. At that point, modern mechanized transport and weapons started to take their toll.

Two notable species that have become extinct, now to be seen only in textbooks, are the white-eyed river-martin and Schomburgk’s deer. Others like the Javan rhino, brow-antlered deer and water birds like the sarus crane, black-neck stork and giant ibis have also disappeared from Thailand’s wilderness areas. They are just surviving in other Asian countries and some zoos. The kouprey, a species of wild cattle that once roamed a small section near the Phanom Dongrak mountain range along the Thai-Cambodian border has probably become extinct. Last confirmed sightings in Thailand were in 1949. The war in Indochina probably sealed its fate.

One result of this drastic depletion has been that white-rumped and red-headed vulture, which were common, have all but disappeared due to lack of carrion. Poisoned bait meant for tiger was another problem. The vulture would swoop down, feed on the carcass and then perish alongside. In the early 1990s, this was recorded and photographed in Huai Kha Khaeng, a sad sight indeed.

Page 14

Leopard Panthera pardus in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. The area attracts many different species of mammal including elephant, gaur, banteng, tapir, pig, sambar and barking deer. As these are prey species for leopard and tiger, the carnivores often come looking for a meal. Also known as panther, the leopard’s spots are clearly visible in the light of the setting sun. On of my best wildlife photographs ever..!

Certainly there is only one creature to blame and that is the human being. Mankind is primarily responsible for this carnage that continues to this day. Although the process has slowed in some respects and accelerated in others, the consequences continue to devastate the Kingdom year after year.

As one example of the wider consequences, Thailand some years ago experienced devastating floods. These were the direct result of damaged watersheds destroyed by excessive logging with no forethought for reforestation when trees were cut. And although some reforestation is now being undertaken, it is already too late for many areas that have been damaged beyond repair. The suffering by the Thai people as a result of these floods has been appalling.

The bright spot in all this doom and gloom is that much of Thailand’s diverse wildlife can still be found in more than 250 protected areas. Altogether, some 14 per cent of the Kingdom’s land area is now reserved, and although most of the protected areas have severe problems, fresh areas are being set aside all the time. Vigorous attempts are now being made to improve park management.

Two pioneers of this dramatic growth deserve to be remembered. Back in the 1950s, one man’s love for this country’s superb forests turned the late Dr. Boonsong Lekagul from a hunter into Thailand’s foremost conservationist. He was also the country’s leading expert at the time on wildlife. He wrote several books, including ‘Mammals of Thailand’ and ‘Guide to the Birds of Thailand’ that are still used today by students of biology. He founded the Association for the Conservation of Wildlife and successfully lobbied for the passage of the first wildlife and national parks legislation.

The other man who richly deserves a place in the roll of honor of Thai conservation is the late Seub Nakhasathien. He was co-author of the nomination by UNESCO of Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary and Thung Yai Naresuan next door as a World Heritage Site. His untimely death shook the country and put these two protected areas on the map as a place to save at all costs and be admired by everyone.

Thailand’s present system of protected areas consists of some 89 national parks, 47 wildlife sanctuaries and 53 non-hunting areas. Among the national parks, the first to be gazetted (in 1962), and one of the most visited conservation areas in the country, is the 2,168 square kilometer Khao Yai National Park in the province of Nakhon Ratchasima (Korat), near the most westerly part of the Phanom Dongrak mountain range. Bordering it to the east is Thailand’s second largest national park, Thap Lan, at 2,239 square kilometers. The 845 square kilometer Pang Sida National Park lies to the south within the former range of the kouprey. Further east along the border with Kampuchea in Si Sa Ket province there is Khao Phanom Dongrak Wildlife Sanctuary (316 square kilometers) and in Ubon Ratchathani province, Yot Dom Wildlife Sanctuary (225 square kilometers) and Kaeng Tana National Park (80 square kilometers).

Page 16

Kreung Krai, at the mouth of the Huai Kha Khaeng (huai meaning stream), is home to Asian wild water buffalo. Due to the close proximity to the Sri Nakharin dam and reservoir, they are extremely endangered. Barely 50 creatures survive, if that. This gateway to the sanctuary can be penetrated quite easily. This needs serious attention if the area’s wildlife is to survive.

Two pioneers of this dramatic growth deserve to be remembered. Back in the 1950s, one man’s love for this country’s superb forests turned the late Dr. Boonsong Lekagul from a hunter into one of Thailand’s foremost conservationist. He was also the country’s leading expert at the time on wildlife. He wrote several books, including ‘Mammals of Thailand’ and ‘Guide to the Birds of Thailand’ that are still used today by students of biology. He founded the Association for the Conservation of Wildlife and successfully lobbied for the passage of the first wildlife and national parks legislation.

The other man who richly deserves a place in the roll of honor of Thai conservation is the late Seub Nakhasathien. He was co-author of the nomination by UNESCO of Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary and Thung Yai Naresuan next door as a combined World Heritage Site. His untimely death shook the country and put these two protected areas on the map as a place to save at all costs and to be admired by everyone.

Thailand’s present system of protected areas consists of some 89 national parks, 47 wildlife sanctuaries and 53 non-hunting areas. Among the national parks, the first to be gazetted (in 1962), and one of the most visited conservation areas in the country, is the 2,168 square kilometer Khao Yai National Park in the province of Nakhon Ratchasima (Korat), near the most westerly part of the Phanom Dongrak mountain range. Bordering it to the east is Thailand’s second largest national park, Thap Lan, at 2,239 square kilometers. The 845 square kilometer Pang Sida National Park lies to the south within the former range of the kouprey. Further east along the border with Kampuchea in Si Sa Ket province there is Khao Phanom Dongrak Wildlife Sanctuary (316 square kilometers) and in Ubon Ratchathani province, Yot Dom Wildlife Sanctuary (225 square kilometers) and Kaeng Tana National Park (80 square kilometers).

Thailand’s southeast encompasses a system of mountain parks and sanctuaries that also borders Cambodia and whose mountains are known in Thai as khao. These begin with Khao Ang Ru Nai Wildlife Sanctuary (1,030 square kilometers) and Khao Chamao-Khao Wong National Park (83 square kilometers). They are situated in the smallest section of the Kingdom along with Khao Soi Dao (745 square kilometers). At 1,670 meters, this is the highest peak in the area and a wildlife sanctuary. It is linked to Khao Khitchakut National Park (59 square kilometers), whose peak at 1,633 meters, together with Khao Soi Dao, forms a saddle. This system also incorporates Khao Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary (144 square kilometers) in Chonburi province and an open zoo. All the mountains are vital to the region as a watershed, delivering water to lowland farmers. This pattern holds true all over Thailand and the importance of the reserved areas cannot be overstressed. The region receives as much as 3,000-4,000 millimeters of rain a year — more than anywhere else in mainland Thailand.

Shortly after Khao Yai was established, Salak Phra Wildlife Sanctuary was gazetted (1966) in Kanchanaburi province as Thailand’s first protected area set up specifically for biodiversity conservation and wildlife research. Of Thailand’s wildlife sanctuaries, the most important are Huai Kha Khaeng (2,780 square kilometers) and Thung Yai Naresuan (3,622 square kilometers), both World Heritage Sites. Jointly, they form one of mainland Southeast Asia’s largest nature reserves. The diversity of their flora and fauna is unrivalled. Split into two administrative sections (east and west), Thung Yai is the single largest protected area in the Kingdom. Salak Phra, Thung Yai and Huai Kha Khaeng are part of the Western Forest Complex which also includes Umphang Wildlife Sanctuary to the north, Khlong Wang Chao, Khlong Lan and Mae Wong National Parks to the northeast, Sri Nakharin, Chalerm Rattanakosin (known as Tham Than Lot), Erawan and Sai Yok National Parks to the south, and Khao Laem National Park to the southwest. The total protected area in Thailand’s largest forest complex is more than 15,000 square kilometers.

Further south, in Phetchaburi province, Kaeng Krachan sits along the border with Myanmar and is, at 2,915 square kilometers, the country’s largest national park. Down the coast in Prachuab Khiri Khan province, Kui Buri National Park where wild elephant and gaur have the largest herds in Thailand. Khao Sam Roi Yot (meaning mountain of three hundred peaks) National Park contains some of the best shoreline habitat in the Kingdom. This small 98 square kilometer park is the breeding ground and wintering home for many species of water and shore birds.

Thailand’s peninsular coastline of some 1,000 kilometers on both the Andaman Sea and Gulf of Thailand contains many national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and non-hunting areas. Several of these are marine zones or offshore islands designated as protected areas. In Krabi, Phuket and Phangnga provinces, the most notable of several reserves is the newly gazetted Khao Phra Bang Khram Wildlife Sanctuary (183 square kilometers) that is home to Gurney’s Pitta, one of the world’s rarest birds. With less than 25 pairs, this bird is highly endangered. Phangnga Bay, where the famous “James Bond Island” is located, is in fact the southernmost tip of the Tenasserim mountain range that stretches all the way from an area in Myanmar next to Tak province in the north of Thailand. Thaleban National Park (102 square kilometers), and Ton Nga Chang and Khao Banthad Wildlife Sanctuaries can be found in this extreme southern part of Thailand.

However, perhaps the most important reserved area in the south is Hala-Bala Wildlife Sanctuary (433 square kilometers) in Yala and Narathiwat provinces. On the southern border with Malaysia, this area is reported to contain Sumatran rhinoceros, elephant, gaur and many other large mammals like tiger, clouded leopard, black panther and bear. But the rarest, most wonderful residents of all are the Sakai nomad hunter-gatherers who live within the sanctuary. They are rarely seen and not much is known of their numbers or habits. On the western side of the peninsula, in Satun province, the Sakai have unfortunately been introduced to modern ways and in this area have lost their natural heritage as true forest dwellers. Adjacent to Hala-Bala Wildlife Sanctuary, Queen Sirikit Reserved Forest, with a total area of 1,337 square kilometers, was recently established.

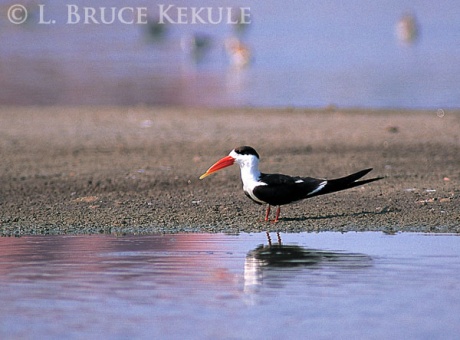

Further north, on the gulf coast in Songkhla and Phatthalung provinces, three linked lakes or lagoons have been gazetted as non-hunting areas. These extend for 80 kilometers along the coast and cover an area of some 1,500 square kilometers. The furthest lake inland is the Thale Noi which has fresh water. Thale Luang and Thale Sap Songkhla are brackish. The most shoreward lake, Thale Sap Songkhla is protected by a sea wall. Large concentrations of shore and water birds can be found on all three lakes.

Another conservation area, in Ranong, Surat Thani and Phangnga provinces, contains Khao Sok, Sri Phangnga and Kaeng Krung National Parks along with Khlong Nakha, Khlong Saeng and Khlong Yan Wildlife Sanctuaries. Their total area is 3,690 square kilometers. Khao Sok is one of the most visited parks in the country.

Probably the most important non-hunting area is Beung Boraphet in the central plains near Nakhon Sawan, the gateway to the northern region of Thailand. At 212 square kilometers, this is Thailand’s largest freshwater lake and is its most important wetland for resident, migrant and winter visiting birds. This magnificent bird sanctuary is experiencing severe problems with overcrowding by people and excessive fishing activities, both of which are detrimental to the balance between the natural environment and the bird population. There are many other smaller marshes and water bodies in the Kingdom but most of these have been encroached upon by rice, vegetable and duck farming, roads, housing and industrial estates. The status of resident and migrant water birds is critical to say the least!

A small system of parks exists in the eastern part of the northeast, adjoining Laos. They include Phu Phan National Park (664 square kilometers), Huai Huad National Park (828 square kilometers) and Phu Si Tan Wildlife Sanctuary (250 square kilometers) in Sakon Nakhon, Kalasin and Mukdahan provinces respectively. They straddle the Phu Phan mountain range.

Doi Inthanon National Park (482 square kilometers) in Chiang Mai province contains, at 2,595 meters, Thailand’s highest mountain (doi, as well as khao and phu, meaning mountain). Other protected areas in the north include Doi Suthep-Pui National Park (261 square kilometers), and Doi Chiang Dao Wildlife Sanctuary (521 square kilometers), both in Chiang Mai province, Doi Khun Tan National Park (255 square kilometers) in Lampang and Doi Luang National Park in Chiang Rai (1,170 square kilometers).

Page 17

Great Egret Egretta alba near the mouth of the Huai Kha Khaeng. There are quite a few around the area and they can be seen here quite easily. These large birds survive on many types of food but fish and insects are their main diet.

In the western area of Esarn, the Thai name for the northeast, within the Dong Phaya Yen and Phetchabun mountain ranges, there is some spectacular scenery, including beautiful forests, and a large system of parks and sanctuaries. The most famous are Thung Salaeng Luang, Phu Hin Rong Kla, Nam Nao and Phu Kradeung National Parks plus Phu Luang and Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuaries. These together cover some 5,339 square kilometers. Several smaller parks are interspersed between them. Phu Luang Wildlife Sanctuary is extremely important as it has some fascinating well preserved footprints of the carnivorous Allosaurus dinosaur that roamed here. Phu Luang is also one of Asia’s most crucial sanctuaries for orchids. It harbors some 160 different species.

The largest single reserved area in the north consists of the Om Koi and Mae Tuen Wildlife Sanctuaries with, to the east across the Ping river and Bhumibol dam and reservoir, Mae Ping National Park. They constitute some 3,400 square kilometers of protected area and are situated in Chiang Mai, Tak and Lamphun provinces. These are the last areas in the north that support a few herds of banteng, gaur and goral, the goat-antelope which lives in the lofty crags of Doi Montjong.

Mae Hong Son province in the extreme northwest contains the important Salawin Wildlife Sanctuary (875 square kilometers) and, adjacent to it, Salawin National Park (722 square kilometers). In the same province are Lum Nam Pai Wildlife Sanctuary (1,181 square kilometers) and Nam Tok Mae Surin National Park (396 square kilometers). A new 1,252 square kilometer national park that adjoins Myanmar has been established in Chiang Mai province at Huai Nam Dang. Lampang province contains Namtok Chae Son National Park (592 square kilometers), while Mae Yom National Park (454 square kilometers) in Lampang and Phrae provinces supports the largest natural teak forest in Thailand, the remainder having being decimated by overlogging. Of note is the fact that the Mae Yom River is the only one in the north that has not been dammed.

There are many other smaller areas not mentioned here but the total area of national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and non-hunting areas around the country is about 70,000 square kilometers. Most of them, sadly, are being or have been encroached upon at one time or another by members of society at all levels. Thailand’s future as a nation that cares about the natural world depends on many factors. Hanging in nature’s fine balance, only time will tell whether this country’s superb natural heritage will continue to survive. The Royal Forest Department has a tremendous load on its shoulders to save and protect the Kingdom’s remaining forests and wildlife. It is hope they will succeed in this extremely difficult task.

CHAPTER ONE

HUAI KHA KHAENG WILDLIFE

SANCTUARY:

A magnificent World Heritage Site

Page 18

Sambar C. unicolor down at the river one afternoon for a refreshing drink. Wild water buffalo have just been here, so the mother is very alert, watching for any predator that might be lurking nearby. The young buck’s antlers are in velvet. The other sambar, a very young doe, then watches its mother drink. These deer then play in the river for a few moments before disappearing into the forest. They still survive in good numbers throughout the sanctuary.

Thailand’s most famous wildlife sanctuary, and World Heritage Site, is nestled in the eastern foothills of the Thanon Thongchai Range. Huai Kha Khaeng is a 2,780 square kilometer (1,073 square mile) area located in the central province of Uthai Thani and lies adjacent to Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary, another World Heritage Site. To the north of Huai Kha Khaeng is Mae Wong National Park and Umphang Wildlife Sanctuary. These are all part of one of the largest conservation areas in mainland Southeast Asia.

Wildlife sanctuaries differ from national parks in that they are not open to the general public and have been set aside for research and biodiversity conservation. Huai Kha Khaeng was gazetted a wildlife sanctuary in 1972 and became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1991. This status was achieved through the efforts of several people, the most notable being that of the late Seub Nakhasathien who at that time worked for the Wildlife Conservation Division of the Royal Forest Department. He took his life in the cause of nature and conservation after fighting a losing battle against poachers and encroachment. The impact of his untimely death in September 1990 really shook the country and the area has now become a place to admire and save at all costs.

At the sanctuary headquarters, a museum has been dedicated to the memory of Seub and portrays his work and dedication to conservation. In the surrounding area, one can enjoy wildlife in its natural habitat. Sambar, barking deer, civet cat, porcupine and rabbit can be seen during the night and occasionally during the day. There are 355 species of forest bird in Huai Kha Khaeng and the sanctuary is truly a bird-watchers paradise. As an example, 22 of 36 species of woodpecker found in Thailand are reported in the sanctuary.

The interior is where the sanctuary really lives up to its name as a World Heritage Site. This is where Huai Kha Khaeng’s biodiversity is truly unsurpassed. The diversity of flora and fauna is something that one has to see to believe and understand. The sights and sounds of peafowl in the morning and evening, the doglike call of barking deer evading a predator and the dawn chorus of gibbon, along with hundreds of songbirds, are a true wonder of nature. Huai Kha Khaeng has mixed deciduous forests that still harbour many rare species like tiger, gaur, banteng, wild water buffalo and elephant. Of Thailand’s 297 mammal species, 67 are recorded here. The sanctuary is one of the last wild riverine habitat ecosystems left in Thailand.

Despite this beauty and richness, the wildlife is being poached at an alarming rate by indiscriminate hunting. Poachers slip into the sanctuary, hunting large mammals such as elephant, gaur, banteng and sambar for their trophies and skins. These end up in homes and business establishments as wall trophies and ornaments. The tiger is hunted for its bones and pelt, the bear for its gall bladder and the serow for its head that is supplied to the Asian medicine trade. Some animals are also taken alive for sale in wildlife markets.

The market for wild meat, supplied to some restaurants offering wildlife on the menu, such as deer, wild pig and bear paw, to mention just a few, is another major problem for Thailand’s fauna. Smaller animals like civet, porcupine and monkey, plus many others, are also menu items in these restaurants. It is without doubt that this onslaught to supply the black market has pushed many species to the brink of extinction, a situation that needs serious attention.

Huai Kha Khaeng also has serious problems with forest fires every year. They are usually started outside the sanctuary by unscrupulous people to open up the forests so that poaching and movement is made easier. These people once lived off the land deep in these forests and were evicted by the Government when Huai Kha Khaeng was gazetted.

However, brush fires are thought to help regenerate new grass and feeding grounds for large herbivores, thus the benefits of fire should also be recognized. These fires should be controlled at an early stage after being detected to prevent serious damage to the evergreen forests that can be permanently damaged.

Page 19

Wild Water Buffalo Bubalus bubalis. This old cow’s horns are huge and estimated at some two meters around the curves. Her dorsal ridge is very prominent. Sadly, she limps in and out of the water, probably due to an old wound. She stays in for an hour after the herd leaves, just chewing her cud and enjoying the coolness of the river. With less than 50 individuals remaining, they are extremely endangered.

There are many mineral licks in the sanctuary that are visited by elephant, gaur, banteng, sambar, barking deer, Asian tapir and wild pig. These animals take in trace elements as a natural and important part of their diet. Occasionally, a glimpse of tiger, leopard and Asian wild dog preying on large mammals is possible. Smaller carnivores like the Asian golden cat and crab-eating mongoose are seen from time to time, and carnivorous reptiles like the forest monitor lizard also come looking for prey. Many birds such as the vernal hanging parrot, thick-billed pigeon, mountain imperial pigeon and green peafowl also visit the licks to take in the mineral-rich soil.

One of the most endangered animal species in Thailand at present is the wild water buffalo. Surviving only in the southern reaches of the Huai Kha Khaeng valley close to the Sri Nakharin dam and reservoir, they are in serious jeopardy from poachers. There are probably no more than 50 buffalo left and they are inbreeding now due to low numbers. They are not long for this world unless some extremely tough sanctions can be brought to bear on those who dare enter the sanctuary to poach these dwindling animals.

Some of the old bulls and cows are extremely dangerous when encountered. They will charge instantly in a direct line to pulverize the enemy. They can ceash through tree saplings and bamboo like a bulldozer, but at great speed, to gore the intruder. Their eyesight is fair, but like all wild bovine their senses of smell and hearing are acute. However, it is the buffalo’s determination that makes it the most dangerous animal in the forest. A big solitary bull can weigh a ton and produce footprints eight inches across, the size of dish plates. They can use their huge horns with great accuracy to gore and throw a poacher or other unfortunate person who happens along into the trees as they charge past. They will continue the attack until the enemy is completely annihilated.

Photo by: Whutipong Tongpeen

Page 20

Asian Elephant Elephas maximus in Huai Kha Khaeng at a mineral deposit during he dry season. This mature female is taking care of her three young ones. Full-grown elephant need more than 200 liters of water a day to survive. These majestic animals are increasingly endangered. Probably no more than 2,000 remain in the wild of Thailand.

It will be a great tragedy if these magnificent bovines become extinct. They need absolute protection with total enforcement if they are to survive and, even then, their future is still bleak. The impact of losing this tremendous animal forever is real and it would be a sad day for the Thai people and the conservation movement if such an impending tragedy were allowed to happen.

The sanctuary is also one of the last strongholds for green peafowl, commonly known as peacock. Although their numbers are increasing at present, they are still considered endangered. Peafowl are breeding and resident here, and can be seen along the banks of the river, side by side with buffalo, sambar, barking deer and crab-eating macaque, especially during the mating season in November to January. These beautiful birds have acute eyesight so it is difficult to get close, but with patience and a good blind they can be observed and photographed quite easily.

All of this beauty depends on maintaining nature’s own balance. The area needs total protection and therefore should be off-limits to all except those engaged in wildlife conservation research and those officials responsible for protecting and managing the area. It is without doubt that Huai Kha Khaeng is Thailand’s greatest wildlife sanctuary. It lives up to its status as a World Heritage Site but now, more than ever, needs absolute protection and good management if it is to survive. The Department of National Parks and the Royal Forest Department has recently adopted new measures to stop illegal hunting and to combat the fire perpetrators. It is to be hoped they will succeed.

Page 21

Gaur Bos gaurus is Asia’s magnificent wild forest ox. The herd bull at the top and on the right in the lower photograph, is fully mature and weighs close to a ton. The older bull on the left is at the peak of his life. Both bulls are extremely powerful and alert. The short legs and bulk of these two bulls are typical of the species. They have tremendous speed when running and jumping. One of the world’s most majestic bovid species!

Page 22-23

Gaur B. gaurus showing their explosive power as they bolt. The old bull leaping in front was probably making passes at the herd females. The younger herd bull is close on his heels as they both disappear into the forest within seconds. A common trait of these tremendous beasts is to jump over any obstacle while moving through the forest at great speed. They may go for quite some distance before slowing down or may stop short to look back at their trail. When wounded by a poacher, they will flee into dense bush, circle back around to wait and listen for the approaching perpetrator, and then attack from a distance of only a few meters. Their determined charge is all but unstoppable. Some rare photos of the world’s largest bovid in action.

Photo by: Theerapat Prayurasiddhi

Photo above by: Saman Khunkwamdee

Page 24

Banteng Bos javanicus herd at a mineral lick that is also visited by many other animals needing its important minerals. These wild cattle are mostly rufous-brown though some are fawn-coloured. The mature bulls are either chestnut or almost black. All banteng have a white rump and white-stocking feet. They are smaller than gaur and have different shaped horns. These wild cattle have become nocturnal due to poaching pressure but can occasionally be seen in the daytime.

Page 25

Wild Water Buffalo B. bubalis in the lowland river habitat of Huai Kha Khaeng. One of Thailand’s rarest mammals, these buffalo are just surviving only in this wildlife sanctuary. A century ago, they could be found in many large forests countrywide. A small herd of buffalo leaving the river where they cool themselves at midday when they also need a drink. This herd does not stay out in the open or in the river for very long, retreating within minutes for the safety of the bush. They will later wallow in mud to create a protective coating to prevent insects from biting. This is the last stronghold in Thailand for these magnificent creatures. Serious enforcement and protection of the area is needed for their survival. New research on their status should be implemented. Note the severe degradation caused by the Sri Nakharin dam and reservoir.

Page 28

Leopard P. pardus posing on a fallen log late one afternoon at a hot spring. This magnificent black cat came for a drink at the water hole above and stayed for more than an hour. Smaller than the tiger, with shorter legs and body, leopard readily climb trees to rest and wait for prey that may pass by, or to get up to safety from a tiger, wild dogs or a human poacher. One of Thailand’s rarest carnivore species, these cats are hardly ever seen, let alone photographed.

Photo by: Kwanchai Waitanyakarn

Page 29

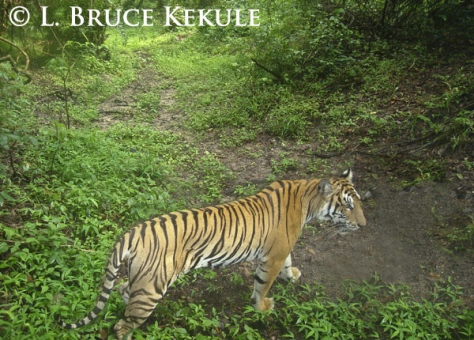

Indochinese Tiger Panthera tigris corbetti. The world’s largest cat, the tiger, has become endangered throughout its range from Siberia down through Thailand, Malaysia and Sumatra and across to Burma and India. It is now extinict in China, west to the Caspian Sea and down to Java and Bali. It was also found in Korea and Japan some 12,000 years ago. Due to extreme hunting pressure for the Asian medicine and trophy trade, less than 250 of these magnificent cats are estimated to remain in Thailand. Tiger are true carnivores and prey on pig and deer primarily. However, they also have been known to take fish, big insects, tortoise, porcupine, banteng, gaur and baby elephant. On very rare occasions in Thailand, they become maneaters. This happens when old age, sickness or wounds make the tiger unable to hunt its natural prey.

Page 30

Leopard P. pardus in bamboo, photographed from the author’s truck one afternoon, not far from the headquarters area. This mature carnivore is on the prowl for prey and crosses in front of the author. It then jumps up the bank and watches for a few moments before disappearing into the bamboo. A quick glimpse and rare photo of the second largest cat in Southeast Asia.

Page 34

Asian Wild Dog Cuon alpinus hunting for prey. The pack comes very close to the author’s photo blind on two separate days, moving very quickly through the area. These carnivores usually hunt in packs of six to 20 animals. They prey on herbivores like sambar and barking deer and have been known to take prey as large as banteng and gaur. When in packs, they are probably the most feared of all the predators in the forest and will occasionally even take on a tiger.

Photo by: Theerapat Prayurasiddhi

Page 35

Asiatic Jackal Canis aureus. A small carnivore doglike animal, the jackal is nocturnal, sleeping in a hole during the day but sometimes comes out in the late afternoon. It has been known to hunt alongside the larger Asian wild dog. It is omnivorous but prefers carrion, often following a tiger to feed on its kill after the cat has left it. It also hunts for small mammals, birds, amphibians and reptiles. Unlike the wild dog, it normally runs alone or in pairs during breeding season. Both photos taken during the afternoon.

Page 36-37

Sambar C. unicolor herd during the mating season in December (top). After several failed attempts to entice females in the herd, the stag (lower) takes his frustration out on the ground. These are rare photos of nature in action. Sambar are Thailand’s largest deer and their colouring differs with age and sex. Like most of the deer species, the males have antlers whereas the females have none. They are more browsers than grazers, preferring areas of secondary growth.

Page 38

Common Barking Deer and Sambar taking in minerals. These deer, the most common in Thailand, inhabit all types of forest. Their distinctive alarm call can be heard over quite long distances. When escaping from danger, they flip their tails erect. Smaller than sambar, barking deer are solitary for most of the year. They form mating pairs during the rutting season only. Sambar tend to stay in herds but the bucks become loners until the rut.

Page 38-39

Dry deciduous dipterocarp forest that is common in the sanctuary. The red tree, Gardenia erythroclada, in the foreground is found all over this forest. Many species of wildlife thrive here. From the road inside the sanctuary, it is quite common to see barking deer and wild pigs, and sometimes a leopard.

Page 39

Common Barking Deer at a hot spring to take in minerals. The mature male (above) has a perfectly shaped set of antlers whereas the females (below) have none. Although common throughout Thailand, these deer are hunted for their meat. They can coexist with man but are mostly nocturnal in their feeding habits and hide during the day.Many other animals visit this area including gaur, banteng, tapir, sambar, wild pig, leopard and tiger.

Changeable Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus cirrhatus on a barking deer carcass at a hot spring. The deer was probably killed by a pack of Asian wild dog and then abandoned, a common trait of these predators but also may have succumded to nature. These large birds have broad wings and long tails. They glide and soar, always looking for a meal. Hawk-eagles are predatory and sometimes scavenge.

Page 40

Wild Pig Sus scrofa (above and right) at a mineral lick. Pig is a prey species of tiger, leopard and wild dog, but they have also been known to be killed by a large solitary boar. Wild pig are omnivorous and feed on fungi, roots, bulbs, shoots, snakes, invertebrates, rats, carrion, and many different types of fruit and vegetables cultivated next to forests. The carcass (bottom left) is that of a gaur. The wild pig is quite common in Thailand’s forests but is poached for its meat and trophy tusks.

Page 41

Wild Pig Sus scrofa at a mineral lick. Pig are prey species of the tiger, leopard and wild dog, but they have also been known to be killed by a large solitary boar. Wild pig are omnivorous and feed on fungi, roots, bulbs, shoots, snakes, invertebrates, rats, carrion, and many different types of fruit and vegetables cultivated next to forests. The carcass (top) is that of a gaur. The wild pig is quite common in Thailand’s forests but is poached for its meat and trophy tusk.

Page 42

Crab-eating Mongoose Herpestes urva hunting for aquatic animals in a hot spring. This animal can squirt an odoriferous fluid from an anal gland with great force, much like the North American skunk. It weighs about 3-4 kilograms and is much larger than the more common Javan mongoose that is found all over Thailand. The crab-eating mongoose is a fearless little carnivore that does not hesitate to enter water in pursuit of prey and is an excellent swimmer.

Three-striped Palm Civet Arctogalidia trivirgata. This little carnivore gets its name from the three longitudinal stripes along its back. It also has a thin stripe on the nose and distinctively shaped ears. This creature is nocturnal and arboreal, preferring deep forest away from humans.

Hog Badger Arctonyx collaris. This nocturnal carnivore has a piglike nose, short tail, white throat and sharp claws. It is terrestrial and sleeps in burrows during the day. Notoriously savage when attacked, and gifted with a tenacity for life, it is one of Thailand’s many strange-looking mammals.

Page 43

Large Indian Civet Viverra zibetha. This magnificently marked civet is sturdily built. Being a carnivore, it eats fish, birds, lizards, frogs and insects, and has been known to scavenge garbage dumps and raid poultry farms. They have a strong distinctive scent that comes from its perineal gland.

Page 44

Sunset at Khao Ban Dai guard station in the central sector of the sanctuary. The area often affords some magnificent sunrises and sunsets as moisture in the atmosphere, drawn from the forests, creates a superb array of colours and hues.

Page 45

Huai Kha Khaeng and Huai Mae Dee junction at Khao Ban Dai ranger station. Sambar, green peafowl and crab-eating macaque come to the river almost daily. Occasionally a tiger or wild pig will cross.

Page 46

Phayre’s Langur Presbytis phayrei. Two langurs feeding on a berry tree in Huai Kha Khaeng. Groups of these long-tailed leaf monkeys, ranging from about a dozen to more than 40 animals, have been seen, as well as solitary creatures that have left the troop. They come down from the trees to drink at mineral springs that cause gallstones that are used in Asian medicines. This, and the fact that their meat is considered a delicacy by some, means that they are heavily poached in the west and north of Thailand.

White-handed Gibbon Hylobates lar in a fruit tree (top). They have white hands and feet, hence their name, and a white ring around the face. Gibbon are dark brown to black or blond to very light brown. The musical “whoop-whoop” call of the species when the sun comes up is a reassuring sign that the forest is more or less intact.

Page 47

Crab-eating Macaque Macaca fascicularis in bamboo ((lower). This monkey is feeding on the tender shoots in the early morning along the Huai Kha Khaeng. Macaque, a prey species of the leopard, are constantly on the alert for the feline.

Page 48

Black Giant Squirrel Ratufa bicolor. This is Thailand’s largest squirrel. It usually comes out midmorning to feed on fruit and nuts. Black with yellow under-parts, its tail is over a foot long. Extremely wary, it will disappear into the trees at the slightest hint of danger.

Page 49

Belly-banded Squirrel Callosciurus flavimanus. This little mammal was photographed at the sanctuary’s headquarters area. Many squirrels can be seen quite easily in the morning, feeding on fruit and nuts. Thailand has some 27 species of squirrel including flying squirrel.

Page 50

Page 51

Green Peafowl P. Muticus in November, during the breeding season. The females (top) are being shown magnificent courtship by the male (below). The male’s trumpet call is very distinctive and can be heard over long distances at early morning and dusk.The male, female and two chickswere photographed at midmorning near Kreung Krai, close to the mouth of the Huai Kha Khaeng. Peafowl are breeding here and their numbers are stable at the moment. However, they have disappeared from all other areas of Thailand with the possible exception of a few in Mae Yom National Park, Phrae province, and the Salawin Wildlife Sanctuary in Mae Hong Son province.

Photo by: Loong Waitnayakarn

Brown Hawk-Owl Ninox scutulata. This group is comprised of two young chicks with the parents on either side. They often stay together for some time after leaving the nest, eventually splitting up to live solitary lives until the mating season. Like all owls, they are nocturnal and have forward-facing eyes, with a facial feathered disc to locate prey at night.

Photo by: Kwanchai Waitnayakarn

Page 52

Collared Scops-Owl Otus lempiji. These birds of prey are seldom seen as they roost in deep cover during the day and only come out at night to feed on various birds, rodents and other small animals. Occasionally, they can be seen during the day but those occurrences are rare.

Page 53

Dry deciduous dipterocarp forest, in the central area, that has just turned green after the first rains in May. This area catches fire during the dry season, almost every year. Areas of evergreen forest are also damaged by fire. Animals often perish in such fires. The underlying danger is posed by the excessively dry seasons that have recently become common. The apparent trend towards a drier climate in Thailand may well be part of global warming and climate change, itself caused in part by forest destruction.

Page 54-55

Blue Magpie Urocissa erythrorhyncha at Khao Ban Dai guard station (lower). This beautiful bird is also very noisy, flying through the forest with a resounding cha-chak, cha-chak. It is a common forest bird, especially in Thailand’s western and northern deciduous and open evergreen woodlands. The photo (top) shows a parent removing chick droppings from the nest. Housekeeping is common among many species of bird, keeping nests clean, and free of insects. Both male and female magpie parents look after the chicks.

Page 56

Blue-bearded Bee-eater Nyctyornis athertoni. This rather large bird nests in dirt banks. Having long, curved and narrow bills, slender bodies and long pointed wings, they feed on bees and other insects caught in flight by hawking from an exposed branch.

Black-naped Monarch Hypothymis azurea. This male is incubating the eggs. With their bright blue plumage, black nape and gorget, these birds are common residents and partial migrants during winter. Their habitat includes deciduous and evergreen forests, secondary growth and open woodlands up to 1,200 meters.

Page 57

Green-billed Malkoha Phaenicop-haeus tristis. This adult is removing chick droppings. The red eyepatch is the bird’s most striking feature. Its plumage is a drab gray-green. This large bird is quite common throughout the country, but the five other species of Malkoha are restricted to the rainforests of the southern peninsula.

Page 58

Brown Hornbill Ptilolaemus tickelli. This large bird is on the ground, feeding an insect to its mate inside the nest. It is rare to find hornbill this far down within the forest canopy. Its size is comparable to the oriental pied hornbill, and feeding habits are similar. They eat fruit, insects and small animals like frogs and snakes.

Page 59

Red-breasted Parakeet Psittacula alexandri and the smaller Vernal Hanging Parrot Loriculus vernalis. This mixed flock is at a mineral lick in the central area of the sanctuary. These two species and some pigeon visit the lick daily, sometimes twice, to take in pebbles and minerals.

Page 60

Banded Broadbill Eurylaimus javanicus with an insect. This is probably the most striking of the seven species of broadbill, with its beautiful crimson breast, black with yellow spotting on the wings and a turquoise bill. Difficult to observe and an uncommon resident, this broadbill is one of the loveliest examples of an arboreal bird.

Page 61

Crimson Sunbird Aethopyga siparaja. The 15 different species of sunbird in Thailand are found from sea level all the way up to the highest mountains. Basically like the New World hummingbird, they are not as vigorous in hovering and flight. These very small birds use their curved beaks to eat nectar and insects. They flit about the forest with endless energy.

Page 62

Lineated Barbet Megalaima lineata feeding on a berry tree at Khao Ban Dai guard station. This barbet is one of the most common of the 13 species found in Thailand. It is frugivorous and normally stays in the upper canopy of the forest. Barbet are heavy-bodied birds with large heads and stout bills.

Page 64

Great Egret and Wild Water Buffalo bull on the river near Kreung Krai, close to the upper reaches of the Sri Nakharin dam and reservoir. Innocent and unaware of the man-made perils around them, they face an uncertain future at the hands of poachers and encroachment.

Page 66

Red Junglefowl Gallus gallus hen with her two chicks at the river. These wild chicken, the ancestors of the domesticated variety, are always extremely wary and can fly away out of danger very quickly, flapping their wings and squawking loudly. Red junglefowl are found all over Thailand but are heavily poached for their meat.

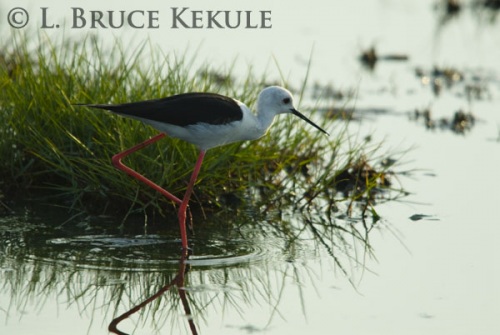

River Lapwing Vanellus duvaucelii of the plover family. This medium-sized wader lives along the lower reaches of the Huai Kha Khaeng. They act as sentries for the wild water buffalo that also live in the area. An uncommon water bird seen only in a few rivers around the country. Very wary and difficult to photograph.

Page 67

Hoopoe Upupa epops. This medium-sized bird with its long beak, crest and striking colors can be found in many countries around the world. Feeding mostly on grubs, it nests in cavities of trees and in earth banks.

Page 69

Water Monitor Varanus salvator swimming along the Huai Kha Khaeng. Water monitor lizards live in a riparian habitat and are very good swimmers. They eat anything they can catch, including fish, birds, other reptiles, small mammals, and any carrion they find. They grow up to two meters in length and can weigh more than 50 kilograms. These reptiles are still found in many places in Thailand, even in the khlongs (canals) around Bangkok.

Page 70-71

Gaur B. gaurus in mid-afternoon at a mineral lick. This magnificent solitary bull, estimated at 12 years old, has worn his horns down at the tips and damaged the bases from years of fighting with other bulls. Truly in his prime, he has survived danger all his life. Gaur are the world’s largest bovid species.

Page 71

Banteng B. javanicus and Gaur B. gaurus bulls grazing on lush grass during the rainy season. This photo of two different species of bovid is rare as normally they are not seen together. However, banteng and gaur have been seen together in Huai Kha Khaeng on occasions at several mineral licks in the sanctuary. Mature banteng bulls have a slightly smaller body size, hooves and horns then gaur bulls of equal maturity. These two bulls probably keep together for added security against tiger attack.

Page 72-73

Asian Elephant E. maximus drinking water in the late afternoon at the mouth of the Huai Kha Khaeng, unaware of their uncertain future. These two and others are seen regularly around the Kreung Krai station. Note the desolation at the drawdown area of the Sri Nakharin reservoir.

To be continued in Part Two..!

Mountains of the North

Majestic beauty, rugged granite massifs, fertile forests, steep terrain, thunderous waterfalls and sparkling waterways

Satellite map of Northern Thailand, Burma and Laos

Doi Inthanon National Park

Some 60 million years ago, the sub-continent India moving on tectonic plates crashed into the Asian mass that created a ripple effect across Southeast Asia, and many mountain ranges up-lifted forming over time. Most of these run from north to south creating a blanket upshot across northern Thailand plus areas in Burma and Laos.

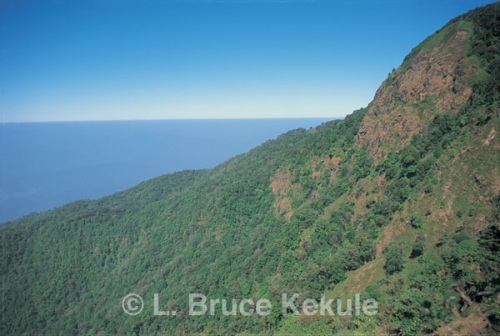

Mountains in Mae Hong Son province

This terrain is divided into many mountains and valleys with rivers that bring life to the region and the people. The North is essentially a series of mountain ridges folded between two mighty off shoots of the Himalayan Range: The Dawa-Tenasserim in the West and the Annamite Range in the East.

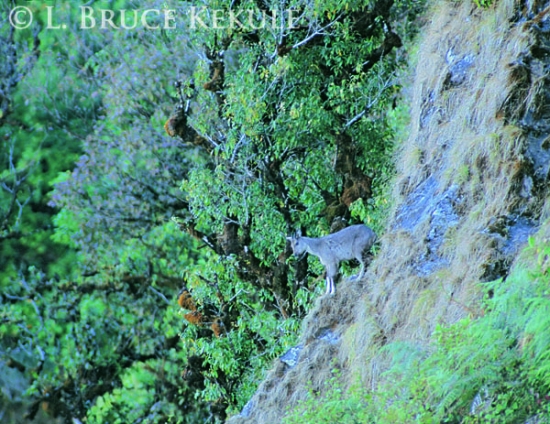

Goral jumping in Mae Lao-Mae Sae Wildlife Sanctuary

The prehistoric significance of animal and plant life is a treasure trove of ancient creatures now extinct. From 80,000 to 140,000 years ago, the giant panda lived in these mountains. Fossil remains have been found in a cave in Mae Hong Sorn by palaeontologists from the Department of Resources with French counterparts. Rhino were common and many remains have come forth.

Wachiratan Waterfall in Doi Inthanon

Going back even further to 10 million years ago, ancestors of the orang-u-tang thrived here and fossil-teeth of these great apes have been uncovered in lignite mines in Phrayao district of Chiang Rai. The rainforests were thick vegetation and ecosystems had a vast array of flora and fauna.

Salaween River in Mae Hong Son province

Approximately 4,000-5,000 years ago, a small group of Hoabinhians (named by archaeologists) or ‘Stone Age’ man were hunter-gatherers, and lived in a narrow valley named Ob Luang gorge southwest of Chiang Mai. These people camped under a rocky ledge near the Mae Chaem River and left red and white cliff drawings depicting the wildlife at the time. The fragmented remains of these prehistoric paintings can still be seen today. These people used stone tools, and depended heavily on wild animals for subsidence.

Siriphum Waterfall in Doi Inthanon

During the Bronze Age, people established permanent settlements nearby, leaving behind signs of civilization using bronze tools, jewellery and pottery. With more advanced weapons, they began to decimate the wildlife and clear the forests for agriculture and a settled existence. With the advent of the Iron Age and increased populations and better weapons, hunters began to have a significant impact on the surrounding flora and fauna. Forest clearing increased as populations became bigger. Settlements along the rivers were the first to be colonized.

Wild boar in Om Koi Wildlife Sanctuary

In the old days, large carnivores like the tiger, leopard and bear were found in all these thick forests. Huge herds of gaur, banteng and elephant lived off the profuse vegetation and proliferated. These mega-fauna lived in the precipitous mountains and thrived on abundant food sources and mineral deposits for supplements. Wild flora and fauna was extremely plentiful and at one time was taken for granted.

Prancing muntjac in Om Koi Wildlife Sanctuary

Around the beginning of the twentieth century, northern Thailand’s many beautiful mountain ranges and valleys were covered with extensive natural teak and deciduous forests. Unfortunately, much of the area has since been heavily logged, cultivated and/or encroached upon.

Orchids in Doi Inthanon

Humans laid siege to the land. When logging concessions were in full swing, living off the land as the loggers penetrated deeper and deeper into virgin forest tracts literally wiped out many places before the logging ban in 1989 and prior to conservation and protection came into play. The logging companies reaped in the profits from the natural resources that had evolved over millions of years. This sad chain of events shows this destruction layed upon the land and the effects of poor watersheds with only fair water retention ability after large scale flooding downstream from the North last year.

Staghorn beetle in Doi Inthanon

At the beginning of winter during November in the north of the Kingdom is a time of beauty. The skies are normally cloudless blue and the weather is crisp and cool. Early morning fog blankets the lower valleys, and rivers and streams run crystal clear. It is at the end of the rainy season and waterfalls cascade down mountain slopes and moisture is 100 percent.

Chiang Saen Lake in Chiang Rai province

In some areas, animals like goral and serow (rare goat-antelopes) still live on rocky crags while deer, wild pigs and wild dogs flourish in steep forests. Birds, insects, reptiles and amphibians plus a huge array of plant life continue to exist. The balance of nature reigns supreme as nature intended. But these biospheres are under greater pressure as time passes on.

Whistling ducks in Chiang Saen lake

For this story, all the provinces from Tak and Uttaradit up to Chiang Mai, Lampoon, Lampang, Mae Hong Sorn, Chiang Rai, Phrae and Nan are blessed with these unique ecosystems. In Thai, ‘doi’ means mountain. The North’s original pristine beauty however now remains primarily in only a few protected areas, the most important of which are described below:

Doi Inthanon National Park

Sunset over Doi Inthanon

Doi Inthanon is Thailand’s highest mountain rising to 2,595 meters, and is part of the Thanon Thongchai Range that extends south from the Shan hills of Burma to the province of Tak. Situated southwest of Chiang Mai, this 482 square kilometre national park was gazetted in 1972 and is now one of the most visited parks in the country. The Royal Thai Air Force maintains a radar station at the peak and the Department of National Parks (DNP) is responsible for the park. This site is visited heavily by Thai and foreign tourists due to its significance as the highest place in the country.

The park’s geology of granitic batholith enables it to support several different types of forest. The most notable of these is at the peak where montane evergreen forest abounds. Native pines grow at the moderate to higher elevations and a sphagnum bog exists at the summit, the only one in Thailand. Important species are the green-tailed sunbird, which is endemic here, and the Himalayan newt (crocodile salamander) found in the bog.

Doi Inthanon National Park was once under full forest cover and wildlife found around the mountain included elephant, gaur, banteng and tiger that was very common here about 50 years ago. However, most of the larger fauna have disappeared due to poaching and encroachment by the hill-tribe and lowland people. A few sambar (Thailand’s largest deer) and smaller mammals like barking deer, wild pig, black bear and a few primates can still be found but all in very small numbers. Goral and serow still survive on Kew Mae Pan cliff-face. Birds predominate the landscape and there are some 383 species that have been recorded here. Doi Inthanon is one of the top bird-watching sites in Thailand.

The influx of hill tribes, first Hmong and later Karen with their practice of slash and burn agriculture has decimated the forests from 1,500 meters down to the lowlands. Opium was once the Hmong’s main cash crop but has now been replaced by rice, vegetables, flowers, fruit and coffee. In the old days, the Karen people were mainly hunters and filled the pot with anything edible. With an ever-increasing population who now use modern agricultural techniques and mechanized transport, this park is under serious threat as the population increases. There is nowhere to go except to expand outwards.

Like most protected areas in the country that have people living in them, it seems that parts of Doi Inthanon have degenerated to the point of no return. The park has been overcome by modernization and it will continue to decline. Probably the most destructive is the amount of pollution generated by vehicles (cars, vans, pick-up trucks and buses) plying the road daily in the thousands that continues to increase. Recent surveys of birds have encountered a drop of some 50 percent over the last 10 years. Unfortunately, it is a downhill run to extinction for many species of flora and fauna at this location.

Doi Suthep – Doi Pui National Park

Sunset over Doi Suthep – Doi Pui National Park in Chiang Mai

The twin peaks of Doi Suthep and Doi Pui, west of the city of Chiang Mai rise from the valley floor to heights of 1,601 and 1,685 meters respectively. The 261 square kilometre national park was finally gazetted in 1981. Unfortunately, due to its proximity to the city, it has been extensively logged and poached for everything it contains. Wild orchids, other flowers and plants, plus mammals, birds have been the prime targets. Once upon a time, elephants, gaur and tiger were common but were quickly decimated by the nearby population.

The park contains two waterfalls, Huai Kaeo and Monthathan that the locals use for recreation. Several Buddhist temples dot the park, the most famous being Wat Phra Borommathat Doi Suthep that is visited by tens of thousands of local and foreign tourists each year. The road at the top to Phu Ping Palace has been widened and other road surfaces have been improved. Continued pressure on the park from more and more traffic and visitors can only have an adverse effect in the long term.

Mae Tuen and Om Koi Wildlife Sanctuaries

Situated in Tak and Chiang Mai provinces respectively, these important contiguous sanctuaries together cover an area of some 2,397 square kilometres. They thus constitute the largest conservation area in northern Thailand. They are bordered to the east by the Mae Ping National Park that is bisected by the Ping River flowing into the Bhumibol reservoir in Tak province. Unfortunately, the lake acts as a gateway to the sanctuaries and park by allowing easy access by boat. The locals are allowed to fish the reservoir but poaching and gathering continues to be a problem for the DNP.

Goral is found here too with a dozen or so animals on Doi Montjong in Om Koi Wildlife Sanctuary. Unlike the serow, which is found more widely in Thailand, the goral is highly endangered. Its future is grim indeed as many Hmong and Karen hill tribes still live within the sanctuaries, engaging in poaching, encroachment, and slash and burn agriculture. This is also one of the last sites in the North for wild elephant. Only a few herds remain. Gaur and banteng are reported but their numbers are few. As time marches on, they could eventually disappear from these two sanctuaries that together constitute the largest northern refuge for Thailand’s large mammals. Very few surveys have been conducted here.

Smaller parks and sanctuaries

There are many other areas in the north that have been designated as national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and non-hunting areas. Of these, the most notable are Mae Lao-Mae Sae and Doi Luang Chiang Dao wildlife sanctuaries in Chiang Mai province, another haven for goral; Namtok Mae Surin National Park, and the Salawin and Lum Nam Pai wildlife sanctuaries in Mae Hong Son province; Doi Khun Tan and Namtok Chae Son national parks in Lampang province; Mae Yom National Park in Lampang and Phrae provinces; and Chiang Saen Lake Non-Hunting Area in Chiang Rai. All these and many other sites not mentioned here are like the rest persecuted by a small minority of people who seem intent on continuing to abuse Thailand’s natural resources for their own benefit. As human populations in the north continue to increase, encroachment into protected areas becomes more difficult to control. The future seems bleak.

Looking back, trying to apportion blame for the enormous damage that has been wrought would be rather like the pot calling the kettle black. Yet if we could turn the clocks back 100 years, and if all those responsible had used careful selective cutting and true conservation techniques, most forests could have been saved. Dwelling on hindsight is thought by many to be a waste of time. Yet hindsight provides us with valuable knowledge, if only we take a little time and trouble to learn from the mistakes made by those who came before us. Using that knowledge today will enable us to save Thailand’s remaining natural treasures for our children and future generations.

Hornbills: Indicator species of an intact ecosystem

WILD SPECIES REPORT

Majestic birds and living fossils

Wreathed hornbill in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Most people are familiar with the hornbill, nature’s amazing avian fauna with large bills and a casque, and some with raucous calls. They also have strange but interesting nesting habits and the larger hornbills make a loud whooshing noise when flying sounding much like a locomotive, and heard from quite a distance. In any given forest, if they thrive it means the ecosystem is fairly intact.

Brown hornbill at a ground nest hole in Huai Kha Khaeng

The hornbill belongs to an ancient family (Bucerotidae) of birds seen in fossils from the strata of the ‘Eocene’ period of Europe some 50 million years ago. Through tectonic-plate movement, hornbills however have become restricted to tropical Africa and Asia, and there are 55 species found in the world with 24 in Africa and the rest surviving in the forests of South and Southeast Asia. Thailand has twelve species recorded throughout the country, and all still thrive but some are endangered.