Posts Tagged ‘world heritage’

Banteng: Endangered Herbivores

WILD SPECIES REPORT

Banteng: Endangered herbivores

Magnificent wild cattle of Southeast Asia

Bovids threatened with extinction

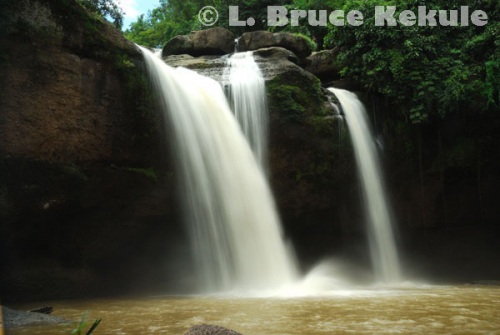

It was a hot steamy morning deep in the wilderness of Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, a World Heritage Site located in the central province of Uthai Thani. Not much was stirring other than a few birds and insects as the sun rose high in the sky. A hot breeze whiffed through, and heat shimmered from the center of a natural mineral deposit several hours walk from the nearest road. As the day got hotter, thirst kicked in among the many species of herbivore that live in the forest nearby.

Banteng bull in Huai Kha Khaeng

Muntjac (barking deer), sambar, banteng and gaur use this important source of minerals. Many smaller mammals, birds, and reptiles also come to the lick as part of their everyday life. Tiger, leopard, and wild dog frequent the area in search of prey. Occasionally, wild elephant stop for a drink. A male barking deer stepped cautiously down to the water hole. Moving slowly and constantly watching out for predators, the young buck took a long-awaited sip of the life giving minerals. Shortly after, it disappeared back into the forest it had come from. Silence again took precedence as the morning wore on.

Banteng bull and cow in Huai Kha Khaeng

About an hour later at the top-end of the clearing, a herd of twelve banteng magically appeared and went straight down to the waterhole, as their kind have done for aeons. The herd included one old bull, a couple of young bulls and cows, plus three calves, and, like the deer, were extremely alert for carnivores. All of a sudden, a cow snorted an alarm, and the herd bolted for the safety of the bush. Curious by nature, the herd bull stopped short near the forest edge for one last look. The herd surrounded the bull and the young calves trailed behind before disappearing into the trees. For a moment, they were vulnerable to attack by predator. Banteng are very sensitive to any disturbance and flee immediately on the first hint of danger.

Banteng on the run in Huai Kha Khaeng

Another hour went by and suddenly, a solitary banteng bull appeared from the forest and moved down to the waterhole but stayed only momentarily. These loners usually pursue the herd during the mating season and have an irresistible urge to mate with the females. However, the herd bull will keep the young bulls in check.

The spirits of the forest had just provided a vision; some beautiful moments in the lives of banteng, Southeast Asia’s wild cattle. My friend Robert Semon and I were sitting in a photographic blind set up just inside the forest edge, but with an open view to the water hole. Banteng had been the main photographic objective on this trip, and it was magnificent seeing and photographing these wild bovids. My camera was very busy during that short period. As it was the first time I had photographed them, the encounter will be forever etched in memory.

Mature banteng bull in Huai Kha Khaeng

Coming back to Huai Kha Khaeng a couple of years later, my team erected a photo-blind while I went looking for tracks. A large granite rock sits in the middle of this oasis in the forest, so I paid my respects to the spirits of the forest thanking them for my previous good fortune here. It was about an hour’s walk back to the truck, and another hour to camp, but I was feeling lucky. After dinner, and a few drinks with the team, I retired to my hammock for an early wake-up.

The next morning I was in the blind at 6am and, after a three-hour wait, a lone banteng bull lumbered down to the waterhole for a drink. My wish had come true. After getting very close to the blind, he sensed danger and bolted. I shot several rolls of film. Alone, the bull was open to attack by tiger or wild dogs. It was very exciting photographing this beautiful creature.

A couple of years later, on one of my many forays into Huai Kha Khaeng, I decided to stay overnight in a permanent photographic blind set-up along the banks of Huai Mae Dee, a tributary of the Huai Kha Khaeng. That night as I lay in my hammock, I wished once again to see banteng. The next morning, the mist was thick as soup, coating the forest with dew. My focus was on a mineral lick across the river. Many rare species of large mammal visit this natural deposit for a drink, and a nibble on the lush grass growing on the rocky slope. A female muntjac nervously appeared, took a drink but quickly departed.

Banteng cow on the Huai Mae Dee

At about 8am, as the sun was just peaking over the treetops, a large herd of banteng stepped out into the mineral lick. There were five bulls and numerous cows and calves in this herd totaling 18 banteng, and it was an exciting ten-minute session. It was during the mating season, the reason so many bulls had come together. I was shooting a digital camera by now and did not stop photographing them until the last one had gone. As always, I gave thanks to the spirits of the forest for my good fortune.

The accompanying photographs show the beauty and gracefulness of these magnificent ungulates. Over the years, I have seen these wild cattle many times, not only in Huai Kha Khaeng (present herd estimated at over 250 individuals), but also over in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary, eastern Thailand (about 80 banteng). These two santuaries are the last bations of a sizable banteng herd left in the Kingdom.

Banteng cows at a waterhole

Huai Kha Khaeng still retains the best prey/predator relationship with many tigers and a sizable herd of banteng plus many other ungulates like gaur, sambar and wild pig. Khao Ang Rue Nai has very few carnivores but Asian wild dogs do take banteng from time to time. Humans unfortunately, are the most devestating predator and are directly responsible for the disappearence of these wonderful creatures. Trophy hunting and bush meat are the two main reasons for this demise.

The other remaining sites that have recorded banteng but are probably now close to extirpation of the species with very few remaining are: Om Koi Wildlife Sanctuary in the North; Nam Nao and Tap Praya national parks in the Northeast; Salak Phra Wildlife Sanctuary and, Sai Yok, Sri Nakharin and Kaeng Krachan national parks in the west; Khlong Saeng and Khlong Yan wildlife sanctuaries in the south; and Sri Satchanarai National Park in the foot-hills of Central Thailand. Their present numbers are estimated to be no more than a very low 300-500 nationwide.

Fossils of an antelope-like ox named Leptobos was discovered in Early Pleistocene deposits 1.8 million years old in Eurasia. Another ancient cattle found in Europe called Bos primigenius or better known as aurochs were domesticated some 6,000 years ago but died out about 500 years ago. Banteng are common ansestors to Bos bibos, a cattle that inhibitated the vast plains of Asia during prehistoric times. Fossil finds of banteng from the Pleistocene epoch in Bali and Java are common.

Banteng herd on a sandbar in Huai Kha Khaeng

Wild banteng Bos javanicus have a scattered distribution throughout Southeast Asia, and three subspecies are recognized. The Java banteng Bos javanicus javanicus of Java and Bali, the Borneo banteng Bos javanicus lowi, and the Burma banteng Bos javanicus birmanicus, also of Thailand and Indochina. Only a few thousand wild banteng are reported to survive throughout their entire range, since human encroachment and poaching in all the above countries have exacted a heavy toll on them. Their future hangs in the balance. Thailand is no exception and the banteng population has declined drastically since World War II.

Banteng bull at a mineral lick in Huai Kha Khaeng

The Kingdom’s protected areas include national parks and wildlife sanctuaries, and are all controlled and managed by the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP). It is extremely difficult defending these forests from human intervention, and the DNP has a heavy burden to bear. Let us hope that they will succeed in this very important but really tough task!

One alternative to disappearing banteng is a reintroduction program to save the species. There are a few breeding centers around the country with banteng. Unfortunately, most of the stock is Indonesian banteng. Years ago, Kukrit Pramote, Thailand’s Prime Minister using government to government relations, imported Indonesian banteng that were released at Lum Phow Non-hunting Area in Kalasin province. There are about 60 surviving on a 900 rai plot. Only one breeding center at Khao Nam Phu, Kanchanaburi province is reported to have Thai banteng. Several young banteng were taken from Salak Phra Wildlife Sanctuary next door and produced off-spring. Presently, there are about 10 individuals at Khao Nam Phu.

Banteng bull at a breeding station in Salak Phra Wildlife Sanctuary

Another pilot program started in 1991 was initiated at Khao Kheow Open Zoo and 13 banteng (unknown origin) were released to adjacent Khao Kheow-Khao Chumpu Wildlife Sanctuary (144 sq.kilometers) in Chonburi province. There are now an estimated 49 banteng surviving in this herd with a few mature bulls living in a very splintered habitat. Poachers however, are a serious threat here using pipe guns and rope snares left in the forest, and inflict casualties on these reintroduced denzins. DNP needs to make sure they are protected to the fullest.

Rare white-spotted banteng cow – endemic to Huai Kha Khaeng

Banteng have been called the most beautiful of all the wild relatives of cattle. The colouring of young bulls and cows is generally a vibrant reddish brown, though some are fawn. The old bulls in Thailand are mostly blackish-brown, but Indonesian banteng bulls are very dark brown to black in some. Regardless of sex, all Thai banteng have a white band around the muzzle, small white patches over the eyes, white stockings on all four legs, and a large white patch on the rump. Another distinct feature is a black stripe along the spine. The dorsal ridge is pronounced in the large adult bulls. Some Thai banteng have white spots along the flank, but this is not found among the other subspecies.

The skull and horns of banteng are less massive then their cousins the gaur Bos gaurus, but are nevertheless formidable weapons. They use their horns for protection, but the males also use them to decide who will get the females during the breeding season in May and June. Gestation is nine and a half to ten months, and one or two calves may be born. The calves are suckled until they are fourteen to sixteen months old.

Banteng bull and cows at a waterhole in Huai Kha Khaeng – note very dark colored bull

Banteng look very much like some domestic cattle and are probably ancestral to them. In Indonesia and Borneo, banteng have been successfully domesticated and are widely used there. For some reason, this practice has not caught on in mainland Southeast Asia. However, many villagers living close to banteng habitats have had wild bulls mingling with their domesticated cattle, and hybrids have been born. Hybrids have also been reported from some forests in the west where banteng and gaur overlap.

The habitat where banteng are normally found is open deciduous forests and hence banteng are more seriously endangered than gaur. They are grazers and prefer open grasslands. However, they have become more nocturnal due to hunting pressure and are rarely seen during the day, preferring to come out in the open at night. Herds of two up to twenty-five or more have been recorded and usually there is only one mature bull.

Banteng bull and cows at a waterhole in Khao Ang Rue Nai

Solitary bulls, or loners, are quite common, as the herd bull has kicked them out. They will typically shadow the herd, especially during the breeding season when they are hoping for the chance to mate with the cows that come into heat. The herd bull will remain supreme only for as long as he remains fit and has not broken a horn.

The future chances of these magestic creatures is slim. Pressure from humans and increased population growth over the long run can only have an adverse effect on the flora and fauna of the nation. The question is, how long will these magnificent bovid survive and in what places? Can we say that in 50 years banteng will continue to live in their protected areas, safe from human poachers and encroachment. Nature’s clock is ticking relentlessly, and only time will tell.

Wildlife Candid Camera – Infrared cameras ‘trap’ Thailand’s elusive wildlife

Wildlife Candid Camera – Infrared cameras ‘trap’ Thailand’s elusive wildlife

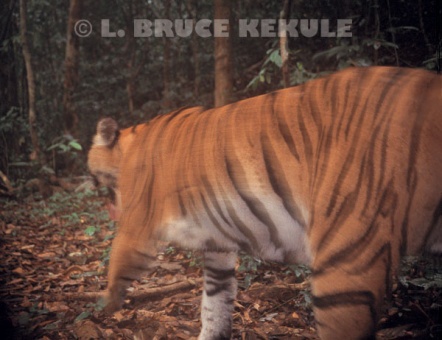

Indochinese tiger camera trapped in Sai Yok National Park

One evening as the shadows were melting into darkness in the jungle of Sai Yok National Park, an Indochinese tiger Panthera tigris corbetti was meandering up to a forest pool for his evening drink. At the planned position, a camera-trap mounted on a dead tree tripped a photograph of the cat, causing it to bound into a bamboo thicket. The tiger could not of course have understood exactly what had just taken place. Instinct triggered its reaction to the flash and the camera’s mechanical click. Taking a photograph of a tiger in the wild is a very daunting task but the wizardry of modern electronics has made the job much easier.

Gaur herd caught at a mineral deposit in Kaeng Krachan National Park

A few days later and just two kilometers away, another tiger pads slowly through the forest topping a 600-meter-high ridge in late afternoon. Its senses are on high alert for any movement or sound that could lead to its next meal. A passive infrared camera-trap set on a wildlife trail catches the tiger as it passes through an invisible motion-detection field. The time and date is recorded and the wildlife photographer has just triumphantly photographed one of Thailand’s rarest mammals in the wild – without even being there at the time; a rare candid wildlife photograph set off by the subject itself.

Mother and cub in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary

Far away in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Western Thailand, a mother leopard guides her young cub to a sambar kill. The carcass is ripe after a few days but still good for a full meal. In early-morning darkness the leopards trigger an active infrared SLR camera and strobe strategically positioned close to the dead deer. When the film was processed, I saw two feeding leopards – a mother and its cub. The female is yellow but the young one is black. Photographs of the notoriously elusive leopard would be far rarer if not for modern technology.

The history of camera traps goes back more than a hundred years. In 1906, pioneer wildlife photographer George Shiras III used a flashlight camera with trip wires to photograph wild animals. His equipment was very heavy and very complicated to use, with the lens aperture being very difficult to anticipate. Two other men experimented with camera traps activated by pressure-plates: F.M. Chapman in 1927 and F.W. Champion in 1928. Their primitive traps produced many superb black-and-white photographs that thrilled magazine and book readers at the time.

Banteng herd at a waterhole in Huai Kha Khaeng

For the last four decades or so, researchers and biologists to collect data on wildlife and also to investigate the secretive and nocturnal lives of such rare and endangered species as the tiger and leopard use camera traps. Beyond glamorous predators, species such as wild cattle, deer and pig are also, without discrimination, recorded to reveal such useful information as relative abundance and activity patterns. Camera trapping can lead to important scientific databases.

The units are most often attached to a tree, usually half a meter above the ground and three to four meters away from water holes, mineral licks, wildlife trails, forest roads or stream beds. The time and date is imprinted on each frame for scientific research.

An American hunter whose goal was to survey designed one of the first camera traps utilizing infrared technology and scout possible locations for big game like deer and bear. These active infrared sensors manufactured by TrailMaster.com in Kansas used a separate transmitter and receiver connected to a small ‘point-and-shoot’ camera which is triggered when the beam between the two units is interrupted by any moving object. A major drawback of active systems is that even an insect momentarily blocking the sensor will stimulate a photograph of seemingly empty forest. Active infrared camera traps are best suited to conditions that are dry with minimal insect activity. Further, three separate units are quite complicated to set up and maintain.

Problems with active infrared systems caused a researcher in Texas to ask a friend to develop a passive infrared camera trap, leading to the establishment of CamTrakker.com in Georgia. Passive camera-traps are a self-contained unit with the camera, batteries and sensing electronics sealed in a box. The sensor detects motion. The chief advantage of the passive system is the ease of a single unit installation with no alignment or external wires.

Asian leopard feeding on a sambar carcass in Huai Kha Khaeng

Passive infrared camera traps, which can work for one month or more between battery changes, have proven the most utilitarian for both researchers and wildlife photographers. The relatively high cost of commercial units is the major drawback, particularly to budget-strapped researchers in developing countries.

Both TrailMaster and CamTrakker have steadily improved their equipment over the years. Other companies have now joined the competition, bringing prices for entry level units down to about US$250 (Top-of-the-line models are about US$500 and CamTrakker offers a digital model that costs US$1,200).

Throughout my early years of wildlife photography, the thought of camera trapping had frequently crossed my mind. Finally, with many years of mechanical experience, I decided to build my own camera-traps. Using existing units as a model, I built a passive infrared camera-trap housed in a 6” x 6” tig-welded aluminum alloy box with a removable front cover. The camera-trap as an enclosed unit that is fixed to a tree using two stainless steel lag bolts contained within the box. A small bag of dessicant (silica gel) is set inside to protect the delicate electronics and camera from moisture, and the front cover is hermetically sealed using silicon sealant and stainless steel screws. The unit is elephant-proof that is very important in the forests I work in. Elephants destroy plastic camera-traps.

Tuskless bull elephant in Kaeng Krachan

Out of my home workshop, I was able to make these custom-built cameras for way less than half the price of imported commercial units. My very close friend Yutdhana Anantavara from Chiang Mai modified the cameras and installed the infrared electronic systems. This early work really helped me onto the road to successful home-made camera traps.

Feral cat camera trapped at my home in Chiang Mai

The first batch of prototype units employed several brands of ‘point-and-shoot’ cameras and different experimental housings. To evaluate each camera’s quality and reliability, I intensively tested each on the domestic cats that regularly walked on top of a wall behind my machine shop. Various films were tested but slide film at 400 ISO proved to produce the highest quality image.

My 1st camera trapped tiger in Sai Yok

To field test the new gear I took a trip to Sai Yok National Park in western Thailand. All of the cameras were placed along wildlife trails, waterholes and mineral licks. Over several months, the film was collected and developed. I was ecstatic when I saw two different tigers, an elephant, serow, muntjac, stumped-tailed macaque, bear, porcupine, water monitor, jungle fowl and wild pigs. The omnivores were the most frequently photographed and probably the tiger’s main prey species. A totally unexpected bonus was photographs of a few poachers.

Serow male camera trapped in Kaeng Krachan NP

Numerous camera trap surveys have been conducted in many of Thailand’s forests. A 2001 survey produced a photograph of a Siamese crocodile in Kaeng Krachan National Park. The croc was caught in broad daylight on a sandbar along the river. Park staff set cameras for a month along the Phetchaburi River. The amazing discovery of this very rare reptile has prompted more investigation into this endangered species. In 2003, I camera trapped a crocodile in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary.

Wild Siamese crocodile camera trapped in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

To analyze wildlife in a given area, researchers use two main techniques: a trail-based survey (where cameras are randomly placed along wildlife trails and roads covering 100 to 300 square kilometers) and a more intensive plot-based method. A smaller plot is chosen (usually 40-50 sq. kilometers) and a camera is placed in each one-kilometer grid. An area can eventually be exhaustively surveyed – the duration depending on the number of cameras used – to prove the presence or absence of tigers and other animals. The data then can be used for conservation management of the protected area.

Indochinese tiger abstract in Kaeng Krachan

Camera traps can reveal very disturbing information. Extensive surveys around Khao Yai National Park indicate that only two tigers survive. The patterns of tigers are as unique as human fingerprints so it is essential to get photos of both sides of each animal so that individuals can be identified. Researchers often set cameras on either side of a trail to capture both sides simultaneously. Khao Yai might have more tigers but the fact that only two individuals are confirmed is depressing. As of 2005, no tigers have been seen in intensive surveys carried out by Kate Jenks from the Smithonian Institute.

Indochinese tiger camera trapped abstract

Poachers have also been camera trapped here. Usually they walk obliviously past the camera but they sometimes damage or steal cameras. Elephants also destroy cameras, tearing the plastic commercial housings off the tree and smashing them or lobbing them into the bush. A Royal Forest Department researcher at Hala-Bala Wildlife Sanctuary in the deep south of Thailand found a unit damaged by elephants, but the camera was still working and developed the film. The last frame shows a very close view of an elephant’s trunk! Some researchers have built stronger steel boxes to protect the plastic units.

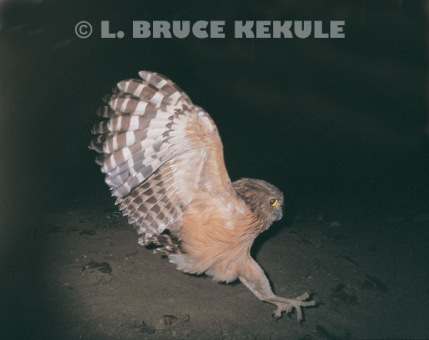

Buffy fish-owl landing by the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan NP

My aluminum-cased camera-traps firmly bolted to a tree have survived many inquisitive elephants. However, they can be stolen or vandalized by determined people who do not want their photo taken. In May of 2005, I lost three cameras near the headwaters of the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan National Park. Forest fires in the dry season destroy cameras. Insects will invade the interior of imperfectly sealed units, playing havoc with their operation. High humidity in the rainforest also damages electrical circuitry, cameras, film and batteries not protected by a well sealed unit and a small bag of moisture absorbing silica gel.

Infrared camera trapping has undoubtedly become a uniquely useful tool for conservation biologists. This ‘candid camera’ is also a blessing for wildlife photographers wanting images of rare and endangered animals. Who knows? In the future, a camera-trap could photograph a species new to science. I’m always excited when I get camera-trap film back from the lab. But the digital age had arrived. Film is being slowly phased out and digital cameras have now overtaken the market dominating it.

Asian Leopard hunting on old logging road in Kaeng Krachan NP

***************************************************************************************************

Wildlife Candid Camera: The Digital Age has arrived

LBK camera trap attached to a tree using Python locking cable

LBK camera trap with Yeticam board and Sony W7 in custom aluminum case

Digital camera traps have now become the new sensation, especially the home-brew (self-made) market. It is now a huge business with a few companies vying for market share. The most predominant are Snapshotsniper.com and Yeticam.com, and they offer parts (sensor boards, lens, battery packs, cases, etc.) to the home builder.

Very old bull gaur at a waterhole in Huai Kha Khaeng WS

My friend Chris Wemmer, the ‘Cameratrap Codger’, was the first person to tell me about a new company in the US producing infrared circuit boards and other accessories for the home-brew camera trap market. The company is Pixcontroller.com. Unfortunately, they no longer offer parts but now sell completed units with digital camera and video.

Mature bull gaur at water hole

As a wildlife photographer, I decided to produce my own digital camera traps using passive infrared circuit boards acquired from the U.S., and digital cameras modified locally with housings and constructed from tig-welded aluminum alloy at my machine shop at home in Chiang Mai. The first cameras used Nikon L11 and L14 cameras and Snapshotsniper boards that were set-up in the forest of Kaeng Krachan National Park in Phetchaburi province in Southwest Thailand over a three-month period in October to December 2008.

Asian tapir – mother and calf in Khlong Saeng WS, Southern Thailand

Animals captured were elephants, gaur, tiger, sambar and muntjac. One camera had over 300 captures in one month at a mineral deposit in the park.

Asian tapir calf in Khlong Saeng

Down in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary in the first part of 2009, I set both film and digital camera traps deep in the forest. Elephants, gaur, tapir, sambar, muntjac, golden cat and Argus pheasant were captured.

Tuskless bull elephant camera trapped at waterhole in Huai Kha Khaeng

I now have more than a dozen digital camera traps using primarily ‘Sony S600’ and W5-7 cameras, Snapshotsniper.com and Yeticam.com circuit boards.

Tusker elephant in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

The Sony cameras have been the best and most durable due to the manual features like ISO and f.stop adjustments. Picture quality with the ‘Carl Zeiss’ lens is usually good.

A herd of wild pigs including a runt in Khlong Saeng

Camera trapping has allowed me the sheer pleasure of seeing Thailand’s amazing wildlife on both film and digital. As of this writing, I have expanded my camera trap fleet to more than 20 units and continue to run a trap-line in Sai Yok National Park. On my first setting in July 2011, I got a mature Gaur bull up a hill in the interior. Still waiting on a tiger.