Posts Tagged ‘serow’

Realm of the Angel Horse

Goral and Serow: Thailand’s rare goat-antelopes

Endangered ungulates surviving on forested mountaintops

Goral kid in Doi Inthanon National Park

For centuries, northern Thai people called them ‘angel horse’ or ma tewada referring to angelic creatures living on mist-shrouded mountains. Goral are even-toed ungulates of the bovid family that includes pig, deer, goat and antelope. They are one of two goat-antelope species found on forested peaks and limestone karst formations that jut from the landscape.

The other goat-antelope is the serow, a larger bovid but found throughout the Kingdom from the north to the south, and east to the west. They mingle with the smaller goral at some locations in the North, primarily in the protected areas. Goral, on the other hand is found only from Tak province up to the border of Burma on the western flank.

Serow male camera-trapped in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Photographing endangered wildlife species has become a bit of an obsession to me. Many of Thailand’s animals have come so close to extinction that their numbers are not counted in thousands or even hundreds but mere handfuls at some locations. Both species are extremely endangered especially the goral.

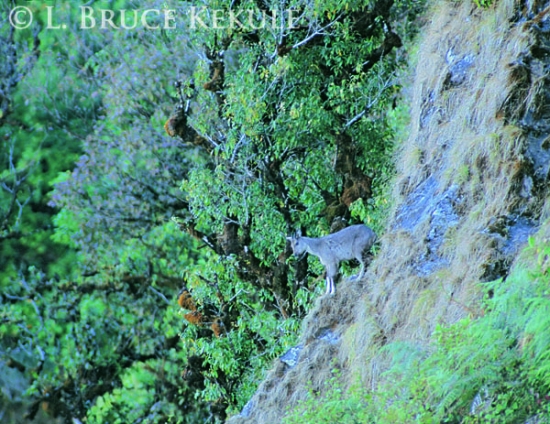

I have photographed goral and serow in their environment but it is fraught by danger due to the sheer cliffs and rocky terrain where they live. On some tracks, one miss-step could end up in disaster. Goat trails worn over thousands of years are engraved on steep mountains throughout the country even though most of these bovid have disappeared from the habitat. Unfortunately, protection and enforcement came a bit too late!

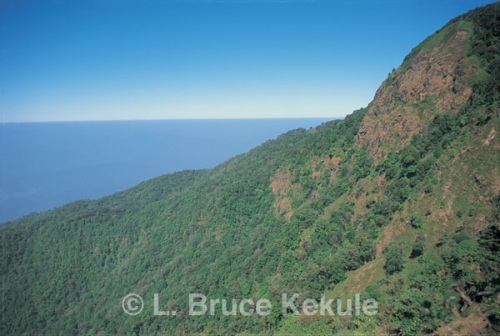

Goral and serow habitat in Doi Inthanon

But the evidence of their past existence still remains. Over the years, I have walked these deeply rutted tracks in the North. At one time, there were absolutely thousands of these goats in the wild.

The estimated population of goral in the country is now about 200-300 individuals based on several recent surveys carried out be the Department of National Parks (DNP) where the goats remained. Some fifteen years ago, only 60 were documented in 6-7 protected areas.

Sunset in Doi Inthanon National Park

Goral are now found in 19 sites as follows: Mae Ping, Doi Inthanon, Ob Luang, Pha Dang, Doi Fas Hum Puk, Namtuk Maesurin, Tumpla-Namtukphasuay, Sisatchanalai, Doi Jong, Sri Lanna national parks, and Omkoi, Mae Tuen, Salween, Chiang Dao, Mae Lao-Mae Sae, Doi Wing La, Doi Luang, Sun Pun Dang, Lum Nam Pai wildlife sanctuaries.

Mae Lao-Mae Sae Wildlife Sanctuary

In Mae Lao-Mae Sae Wildlife Sanctuary, goral still thrive on Mon Liem, a massif some 1,200 meters above sea level. This protected area is about 80 kilometers northwest of Chiang Mai and cover an area of 514 sq. kms. The headquarters is situated on Route 1095 about halfway between Mae Malai, a small town north of the provincial capital to Pai in Mae Hong Son province.

Male goral camera-trapped in Mae Lao-Mae Sa Wildlife Sanctuary

Another great place for these amazing animals is Doi Inthanon National Park some 80 kilometers south of Chiang Mai. It is Thailand’s highest mountain and protected area at 2,565 meters above sea level covering an area of 482 sq. kms. Both species still thrive on the rocky slopes but are persecuted by low land people and numbers remain very low.

Goral and serow are creatures of habit and have places where they stand in the sun during early morning or late afternoon usually on a rock or grassy mound. They can remain motionless for hours on one spot as I witnessed in Doi Inthanon. A male goral stood from about 9am to almost 12-noon as I sat in a freezing blind at 2,350 meters. The temperature here can drop to zero degrees Celsius during the winter months.

Goral standing on a cliff-face in Doi Inthanon

Another habit is to defecate at the same place. Piles of pellets are found wherever they live, usually below a large rock. They also move around and have several sunning locations especially when they have been disturbed. They are extremely shy of humans and will disappear into the rocks at first sight.

These remarkable animals can navigate vertically up or down and latterly if need be, and get most of their nourishment through the vegetation they eat. During the extreme dry season, these goats will seek out a stream or mineral seep for moisture.

Serow camera-trapped in Sai Yok National Park

Mahidol and Kasetsart University (Bangkok) students and professors studying the impact of human settlements near goat habitat, and surveying the remaining wild population have carried out some research on both species. Unfortunately, goat numbers remain very low at all locations, especially the goral.

Dr Rattanawat Chaiyarat and the late Dr Choomphon Ngampongsai with Kasetsart University, and the late Seub Nakhasathien, the famous conservationist with the Royal Forest Department, were the first people to study goral. Dr Vijak Chimchom with Mahidol did his MSC thesis on serow in Sam Roi Yot National Park down in Prachuap Kirikhan province along the coast in the Gulf of Thailand.

Serow heads in oil

Both species have been hunted for their meat, horns and oil that come from boiling the head and bones. Supposedly, this oil is used to relieve arthritis and other bone ailments but this is very doubtful. A man in Chiang Mai pushes a cart around the city with two serow heads in oil selling this so-called remedy seen in the accompanying photograph.

The horns of goral and serow are black, corrugated at the base, very pointed and swept back (like their relatives, the Rocky Mountain goat of North America). Their horns are not impressive but are still sought after by poachers.

Serow heads in oil on the streets of Chiang Mai

The tip of serow horn is used to make deadly knives that are attached to a rooster’s spur used during cockfights, primarily in the South. This large ungulate is eagerly sought after wherever they survive.

The Hmong ethnic people hunt the goral just before their new year in February and believe eating the meat will make them strong. This has brought the goral near to extinction in northern Thailand.

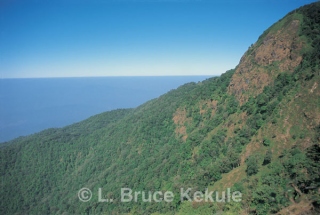

Kiew Mae Pan cliff-face in Doi Inthanon

Over the years I concentrated my photographic efforts on Doi Inthanon. In 2003 after consolations with Anusit Mathavararug, the superintendant of Doi Inthanon at the time to arrange a photograph trip after both species at the cliff-face and made four different trips to the park. On the last day, I got lucky.

On a wind-swept ridgeline, with the temperature hovering around zero degrees Celsius (32 Fahrenheit), I huddled in a small shallow depression early one morning in January. A camouflage net was propped above me by some poles and string. It was freezing cold and my feet felt like two frozen rocks, but my body and head were well covered and warm.

Siriphum waterfall in Doi Inthanon

Several local Hmong (former poachers) helped me get close to goat habitat. The sun was up but still low on the horizon, and the surrounding light was magical. I waited patiently to see and photograph these elusive creatures.

As I scanned the opposite cliff-face for movement, I heard a strange sound about 15 meters below me, off to the side. At first I was not sure what it was or where the sound was coming from. Then I saw this little creature snorting and stamping its feet at me.

Goral kid up-close to my photographic blind

I was an intruder in the kid’s territory and presumed that the youngster’s father and mother had probably been scared off by my scent. Over hundreds of years, these remarkable ungulates have learned that man is to be avoided at all costs.

Then the little goat climbed up and was standing diagonally across from me but still kept its distance as featured in the lead photo. In the meantime, I kept shooting my camera and had to reload film. I was having a great time photographing this young innocent creature. After a few minutes, it went back down and finally disappeared into the alpine brush leaving me awash with joy.

Doi Inthanon in the winter near the summit

Getting that close to one of Thailand’s rare mammals was well worth the effort. All the hardship of camping out in the cold windy and wet conditions, getting up at 4am and walking a kilometer in the steep slippery dangerous terrain disappeared from my mind. The brief encounter is etched in my memory of what innocence in nature really means.

After my success, it became widely known that goral actually did survive out on the cliff in Doi Inthanon, and several other wildlife photographers visited the wind-blown slopes seeking the goats.

Male goral in Doi Inthanon

My good friend Sarawut Sawkhamkhet has made many trips over a three-year period to this place. Most of the time he saw nothing except cold rain and fog. But he has been lucky too photographing a mature goral up close and on several other occasions, a herd of goral; which shows diligence does pay off when one is consistent.

Herd of goral in Doi Inthanon

In the old days, I also visited Mae Lao-Mae Sae making several trips up the mountain. Evidence of a few goral was about and sightings were always brief. Recently, I was invited by the chief Romyen Thongsibsong and my close friend Dr Sawai Wanghongsa to visit the site again to carry out a camera-trap survey. On the very first two-week stint, an old male goral with a broken horn was recorded on one camera shown in this story. A wild pig and piglets plus a large Indian civet were also caught by camera-trap up the mountain.

Old Broken Horn: Male goral camera-trapped at

a salt lick in Mae Lao-Mae Sae in May 2011

In August of this year, the DNP will reintroduce nine goral from Omkoi Breeding Centre into Mae Lao-Mae Sae. A corral facility was erected in the wildlife sanctuary many years ago to accept wild animals saved from poachers and other people who kept them illegally, but was never used. The fenced-in area is about 2 sq. kms. and is now separated into three zones where three goral will be kept in each zone. Six will be collared and a research team headed by Adisorn Kongphoemthun will look after and monitor the animals eventually releasing them into the sanctuary.

Another team headed by Somchai Borisoothi from the Chiang Mai Wildlife Education Centre at the Doi Suthep Non-Hunting Area, will conduct ‘Out-reach’ workshops in the area. They will coordinate with the locals teaching them wildlife conservation, and the importance of saving the goral and other animals in the sanctuary for the future and their name as a conservation village.

Protection will be up-graded to look after this project. Hopefully, this can eventually turn into an eco-tourist attraction where people can visit the sanctuary in the morning and evening, walk a nature trail and then view the goats out on the rocky cliff-face. The money can then go to the rangers for up-keep and patrols.

It is great news that the DNP has taken the initiative in this reintroduction effort to save the goral. Other locations and other animals in captivity should also benefit from a program like this. At the forefront are increased protection and enforcement plus more funding and new personnel to help the rangers patrol the forests. Incentive for these people is imperative.

I hope these photographs and story will instill a sense of awareness, so the powers that be will look after these magical places. The people of the present and future need to see these wonderful animals, and be reassured that the ecosystem is still intact and truly worth saving.

Big Cats in Kaeng Krachan: The tiger and leopard

A look at tiger and leopard evolution in Asia

At the beginning of the dry season in January, the jungle canopy is still mostly green but falling leaves begin to carpet the forest floor as the first cold snap arrives. Some species of trees start their transformation, producing a mosaic of yellows, oranges, reds, browns and greens. For the first few hours each morning, heavy fog blocks out the sun as moisture dissipates from the forest. The Phetchaburi River is crystal clear as it flows through this magnificent forest.

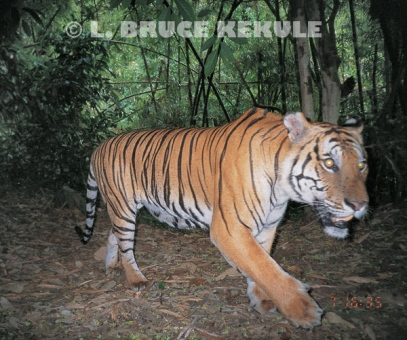

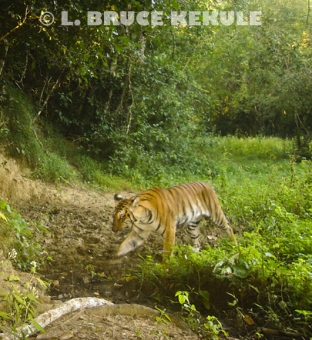

Indochinese tiger camera trapped by the Phetchaburi River

A large predator walks the trails seeking its next meal. Sensing danger, a muntjac barks a warning. The whole community of wild animals is on alert as macaques and langurs cry out from the trees above. A striped carnivore stalks a herd of wild pigs. The nervous omnivores squeal and panic, running through the underbrush to escape. But the big cat is lightning quick – it catches a young pig with sharp claws. The struggle is over in seconds as fangs penetrate to the spine.

Leopard camera-trapped on an old logging road

The tiger has just made a kill. It lifts the lifeless prey into deep cover and devours the carcass. After feeding, the big cat seeks water for a thirst quenching drink. It will then lie down and rest until the desire to eat or drink begins again. Tigers will sometimes move great distances in search of food. But where there is an abundance of prey species, these magnificent cats continue to live in balance with nature. The average kill ratio for a tiger is about twenty unsuccessful attempts for one actual kill. At a certain time of year, the male tiger will seek out a female to carry on his legacy.

Another tiger by the Phetchaburi River

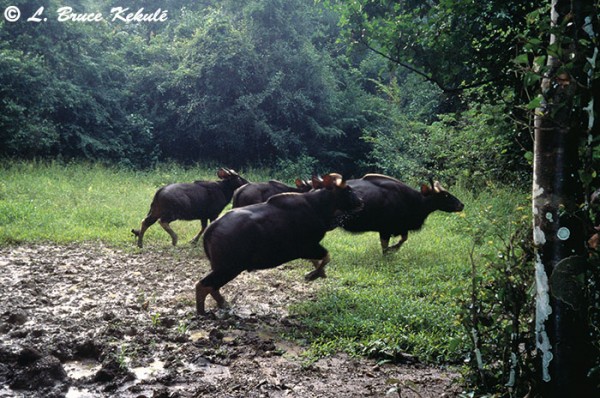

Kaeng Krachan National Park is a great wilderness that sits in the Tenassarim Range in southwest Thailand. It is one of the most beautiful protected areas left in the country. Elephants, gaur, tiger, leopard, tapir, gibbons, hornbills and literally thousands of other plants and animals still survive in a rich ecosystem that is world class.

A tiger camera trapped at a mineral lick in Kaeng Krachan

To understand how the tiger and leopard evolved, we must go back to the beginning of these wild creatures. After the carnivorous dinosaurs died out about 65 million years ago, mammals with sharp teeth, strong jaws and claws replaced them as the top land predators. The first successful mammalian carnivores were the Creodonts that evolved during the Eocene epoch 57-35 million years ago. Creodonts ranged in size from smaller than a weasel to as big as a bear. A bear-dog also evolved during this period. These carnivores all had voracious appetites that were satisfied by large concentrations of prey species, mainly the odd-toed and even-toed ungulates that browsed and grazed the lush forests and plains of the time. The early Creodonts evolved into the modern carnivores that we know today: the bears, cats, dogs and other predators.

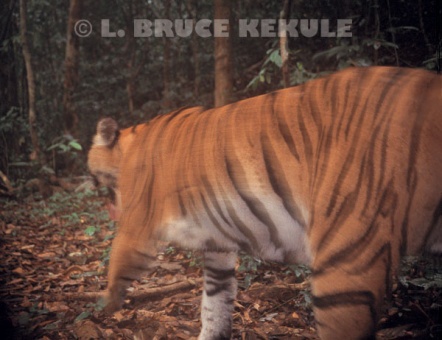

Tiger camera trap abstract

The order Carnivora is separated into three superfamilies: The Arctoidea includes marten, weasel, badger, otter, bear and the panda; the Cynoidea are made up of the dog, fox and the wolf; and the Herpestoidea includes the mongoose, civet, hyena and the cat. Most carnivores are dedicated meat-eaters, but some groups such as civet, panda and bear are omnivorous, eating meat and plants.

Leopard camera trapped on a nature trail in the park

Nimravidae were the first cats to evolve in the Early Oligocene epoch, about 35 million years ago. They lasted till the Late Miocene, some eight million years ago, when huge grasslands had developed around the world. The large saber-toothed cats were the first of the family Felidae. These long-fanged felines evolved alongside huge herds of grazing mammals like antelope and cattle. There were several different species of saber-tooth, but they all became extinct about two to three million years ago.

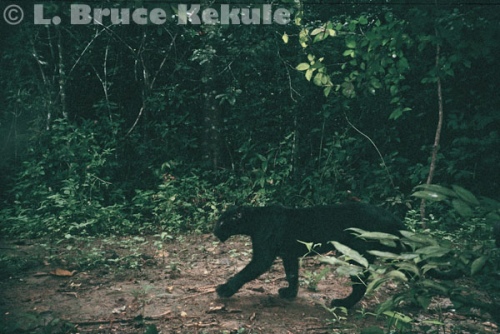

Black leopard camera trapped on the main road in the park

Modern cats belong to the family Felidae and include: tiger, lion, leopard, jaguar, cougar and cheetah, and all the smaller cats such as lynx, bobcat, jungle cat, fishing cat to name just a few plus domestic cats. Wild carnivores feed almost exclusively on vertebrate prey and sit at the top of the food chain. Tiger and lion have few predators apart from man but a pack of wild dogs however are a constant threat to the large cats and their offspring. The tiger and leopard belong to the genus Panthera, or roaring cats, that include the lion and the jaguar.

Leopard camera trapped in the interior

Thousands of years ago when primitive humans lived off the land as hunters and gatherers, they survived by pure instinct. They killed animals for meat and skins, and also gathered many different tools and plants from the forests. As humans became more sophisticated, they used weapons to take down larger animals. Clubs, spears, knives, bow and arrows were all that separated them from almost certain death at the claws and jaws of a predator many times their size.

Black leopard camera trapped on an old logging road

The possibility of being eaten by a carnivore like a tiger or leopard must have been on everyone’s mind that lived in or near the wilderness. Entering the forest where every step could be the last was like walking a tightrope. Attack normally lasted only seconds as a huge predator pounced from behind, biting the neck and causing almost instant death. Very few people survive such an incident. It must have been a scary environment to live in.

The will to survive, however, was strong and men eventually conquered his fear of the wild cats with more modern weaponry. The tables had finally turned and the predators became the hunted. As human populations and settlements grew, the forests were quickly transformed into agricultural land.

An Indochinese tiger on the prowl at night by the Phetchaburi River

After firearms were invented, European royalty, native kings, landlords, planters, foresters, government officials and many adventurers journeyed to the forests of Asia in search of the tiger. Mostly, they came to prove their dominance over the big cat. A trophy of tiger on the wall or floor at home proved beyond doubt that the owner was the supreme species. One could boast of their prowess as a hunter.

But the fact is most hunters shot tigers and leopards from the safety of a tree-blind, vehicle or elephant back. The cats would be attracted to within gun range by cattle, buffalo or a goat used as bait. For special hunts, hundreds of local villagers were recruited as beaters, trackers and mahouts. To join a shikar (Indian word for the hunt) was the ultimate experience for the adventurous.

The same tiger as above a few moments later

More tigers have been killed for sport in India then anywhere else in the world. In the days of the Raj, it was common to see five, ten or twenty cats lying dead on the ground in front of a hunting party. The Maharajah of Surguja killed some 1,157 tigers during his reign. Some Englishmen claimed to have shot more than 100 tigers. Fortunately in 1972, the Indian government finally banned hunting because the tiger and many other species were threatened with extinction.

The most famous hunter ever to overcome his fear of the big Asian cats was Jim Corbett of India. From 1907 to 1939, he single-handedly dispatched scores of man-eating tigers and leopards. His book ‘Man-eaters of Kumaon’ is a classic. Some cats mentioned in the book had killed hundreds of people. Corbett National Park was established in his honor, and the Indo-Chinese subspecies of tiger Panthera tigris corbetti is named after him.

In Thailand, the tiger and the leopard were also hunted for sport but on a much smaller scale than in India. In the past, rural Thai people living near wilderness areas built houses high off the ground that protected them during the night. But daytime was another thing. If they worked in fields bordering thick jungle or they went into the forest, they risked their lives.

At the turn of the 20th Century as modern firearms, agriculture and transportation took hold in the Kingdom, the forests and wildlife began to disappear. Man-eaters also declined. However, during World War II along the death railway in the Sai Yok district of Kanchanaburi province there were still accounts of man-eating cats. In recent times, there has been no such record. From time to time, domestic cattle are still killed by a tiger or leopard but this is now very rare. Low wildlife densities in the forest and easy prey are the main reason for this occurrence.

Thailand is fortunate in that tiger and leopard plus another seven species of cat still survive in some of the larger national parks and wildlife sanctuaries. Kaeng Krachan National Park is one of those protected areas that still harbor the big cats. Tigers can and do kill the leopard. Although their paths do cross, normally the spotted cat will avoid the striped predator. Documentary accounts and photographs do exist of tigers eating leopards.

In 2002-2003 while carrying out camera trap work in Kaeng Krachan in cooperation with the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department, I was surprised and elated to see both species tripping the same cameras in several areas only days apart. In one month, four different leopards, one of them black, were caught on film. In the following month, a leopard was caught during the day, and a huge male tiger stopped and posed for the camera. Both species were using the same trail for their hunting forays. A few other protected areas like Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai Naresuan wildlife sanctuaries have records of overlapping.

In Kaeng Krachan, an important discovery is that tiger and leopard hunt at all times during the day. It is usually thought they are only active in the late afternoon and throughout the night preferring to rest during the day. More research is required if we are to determine the pattern of daytime hunting by the big cats here. It is probably due to the pristine state of this forest and the lack of human activity.

Without doubt, the future of the big cats depends on one thing only – the complete protection of the remaining forests where they live. If the national parks and wildlife sanctuaries remain intact with a high number of prey species, the big cats will survive. But if overdevelopment and encroachment is allowed to continue, these magnificent animals will eventually disappear.

Unfortunately, too much time and money is wasted by too many organizations talking about saving the tiger and other wildlife, with very little actually being done. Human population growth will eventually destroy most wild places. Only true protection by a few dedicated people will slow the destruction of nature’s precious wildlife and wilderness areas. It is only hoped that the tiger and leopard will continue to survive as they have for millions of years.

Leopard – Panthera pardus

The leopard is closely related to the jaguar of South America. Both have a spotted coat pattern, incidence of melanism (black phase), and relatively short legs. The present distribution of the leopard is restricted to Asia Minor, India, Southeast Asia, the Himalayas, Tibet, China, Siberia, and Africa. Fossils of leopards were found in Pleistocene deposits throughout Europe, the Middle East, Java, and Africa, some 1.5 million years old. These secretive cats are mainly nocturnal. Their populations and ranges are difficult to determine but radio tracking of collared animals has shed new light on their movements and area they live in. ‘Spots’ is more tolerable to humans and their settlements.

Tiger – Panthera tigris

According to fossil evidence Panthera cats branched from the other Felidae about five million years ago in Asia. The first tigers originated in eastern China. Fossils of the earliest tigers date back to the Pleistocene epoch, about 1.6 to two million years ago, have been found in Henan, southeast China, and on the island of Java in Indonesia. The historic range of the tiger covered much of Asia and some of its islands.

However, humans have had an enormous impact on the geographic range of the species. The big cat only survives in 13 countries: Russia, China, India, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Burma, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. The present range is less than five percent of the tiger’s former range. There are less than 5,000 tigers left in the wild.

Goats in the Mist: Thailand’s Goat-Antelopes

Goral and Serow – Rare goat-antelopes

Photographing endangered species has become an obsession to me. Many of Thailand’s wild animals have come so close to extinction that their numbers are counted not in thousands or even hundreds but rather handfuls. Goral Naemorhedus goral are one such animal. Surviving on a few scattered mountaintops in northern Thailand, these even-toed ungulates are on the critically endangered list. With fewer than 60 individuals nationwide and low numbers at each site, the goral is considered one of the Kingdom’s rarest mammals.

Goral kid in early morning light at Keiw Mae Pan cliff – Doi Inthanon NP

Acquiring photographs of these goat-antelopes is a daunting task considering their natural habitat. Hunting pressure and encroachment have forced them to retreat to the steepest, most inaccessible limestone cliffs and forested mountains. Goral are still found in seven protected areas including Doi Inthanon and Mae Ping National Parks, and in the wildlife sanctuaries of Om Koi, Doi Luang Chiang Dao, Mae Tuan, Mae Lao-Mae Sae and Lum Nam Pai, all in the north of Thailand.

Another species of goat-antelope surviving in Thailand is the serow Capricornis sumatraenis. Both species belong to the Bovidae family, which includes cattle, sheep, goats and antelope. Bovids are ruminants with four-chambered stomachs. In some areas, goral and serow share the same habitat. They have short bodies with long legs ending in padded, gripping hooves enabling them to inhabit steep mountainsides and cliffs. They eat grasses, herbs and shrubs and gain moisture from the plants they eat. Their keen eyesight provides early warning of danger. Like all bovids, they do not shed their horns like deer do with antlers. Serow are normally solitary whereas goral are usually form small herds from four to twelve individuals.

Male serow caught by camera trap

Serow and goral are creatures of habit. These lofty creatures have favorite places to sun themselves, usually a rock or grassy mound. They can stand for hours on one rock as I witnessed in Doi Inthanon where a goral stood from about 9am to almost 12noon. Another habit is to defecate at the same place. Piles of pellets can be found wherever they live, usually on or around a large rock. Research on both species has now been undertaken by Mahidol and Kasetsart University staff studying the impact of human settlements near goat habitat and surveying the remaining populations.

Unfortunately, both species have been hunted for their meat, horns and oil which comes from boiling the head. Supposedly, the oil is used to relieve arthritis and bone ailments. The horns of goral and serow are black, corrugated at the base, pointed and swept back (like their relatives, the Rocky Mountain goat of North America). Their horns are not impressive but are still sought after by poachers. The tip of serow horn is used to make deadly spears which can be attached to a rooster’s spur during a cock fight. It is eagerly sought after, especially in southern Thailand.

Goral kid close-up

Hunting has decimated both goral and serow populations that numbered in the thousands as recently as 50 years ago. In many mountainous areas hill tribe people live and encroach on the forest for the purpose of slash-and-burn agriculture. This has played a major role in the disappearance of both species in the North. Lowland people also hunted them. In other areas where the serow are found, they have declined due to continued pressure from man.

Two sites were chosen to photograph these mountain creatures: Doi Inthanon National Park about 80 kilometers south of Chiang Mai and Mae Lao-Mae Sae Wildlife Sanctuary some 60 kilometers to the north. Staff at the protected areas confirmed goral and serow were still surviving. Working closely with the Wildlife Research Division in Bangkok. My plan was to set up photographic blinds as close to wild goat domain as possible and use a long telephoto lens. But this was easier said then done.

Keiw Mae Pan cliff in Doi Inthanon

Doi Inthanon, Thailand’s highest mountain, supports several small herds of goral around the summit. The animals are quite often seen close to Kew Mae Pan Nature Trail, developed in partnership with the Electric Generating Public Company Limited (EGCO) and the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department (DNP). Three kilometers from the road, a huge cliff rises some 2,500 meters above sea level and is criss-crossed with goat trails etched from thousands of years of use by goral and serow.

The skies are crystal clear over Doi Inthanon in November. This is truly a beautiful and remarkable place. But it does take some effort to get close to the cliff. The nature trail is strictly regulated and a local guide must be used for the three to four hour trek. If you are lucky and get up early, you may see goral and serow sunning themselves on rocky outcrops near the trail. Take a good pair of binoculars or telescope. This is also a good place for birdwatching, and you may see many species including the beautiful endemic green-tailed sunbird.

Doi Inthanon National Park

Mae Lao-Mae Sae is situated along the highway from Chiang Mai to Pai. A part of the sanctuary is divided by the road and Mon Liem, a giant granite massif, rises up to 1,200 meters above sea level. The sanctuary is home to a small herd of goral that survive on the summit. It is also criss-crossed by goat trails, and huge pine trees hundreds of years old are found here. The view is majestic, especially to the north where Doi Luang Chiang Dao Wildlife Sanctuary, another haven for goral, is situated. Wildlife sanctuaries are not open to the general public since they have been set aside for wildlife and biodiversity research. In October 2001, I glimpsed a male goral near the summit as the sun was going down. The goat unfortunately, was out of photographic range.

In November 2001, I visited the superintendent of Doi Inthanon to arrange a photographic trip after both goat species at the cliff. At 2,300 meters above sea level, temperatures can plunge at daybreak to zero degree Celsius with ice forming on the grass. It was tough getting out of the tent at 4 a.m. but it was important to move into the blind near the cliff face before the sun was up in order to photograph these wild goats. For the best photographic opportunities, the blind had to blend into the surrounding terrain so as not to spook the goats.

After four days of freezing, windy conditions, I spotted goral and serow on several occasions about a kilometer away. While scanning the cliff with my binoculars on the last morning, I detected a slight movement. A closer look revealed a male goral lying down on a buff about 500 meters from the blind. A short while later, he stood up. Using my 600mm Minolta lens with 2X tele-converter, I got some acceptable photographs of him.

This male had a fluffy white throat and underbelly. His gray winter coat was beautiful. After some time he did what goral do best – jumping straight down off the ledge in order to get closer to his mate who was feeding below. They butted heads affectionately a few times before disappearing into the maze of the cliff.

I made four trips to Doi Inthanon during the winter of 2001 and 2002 in search of goral and serow. Several herds of goral are still breeding here and can be seen almost every day. Serow are more elusive and only a few individuals were spotted from time to time. The spirits of the mountain listened to my prayers. On the last day of the fourth trip, a young goral about five months old appeared twenty meters away from me stamping its feet and snorting. It was nature at its best, making the front cover of this book.

Siriphum Waterfall in Doi Inthanon National Park

These wild goats have an uncertain future. Uncontrolled human population growth both inside and outside of the protected areas is bound to affect them in the long run. There is also the danger of disease carried by domesticated cattle and buffalo around the mountaintops decimating wild goats – something that needs to be checked and stopped at all costs.

Hunting of goral and serow continues in some areas, and the poachers are rarely brought to justice. Jail terms are too light and outdated. As a result, these animals need serious efforts to protect them from the dangers of the modern world with all the resources available, or they could vanish from the Kingdom’s mountaintops forever. A crime against nature should be on par with a crime against a fellow human being. Enforcement must be improved and implemented on a long term-basis. The Thai community needs more wildlife conservation education at all levels of society.

Serow – Capricornis sumatraenis

Serow share much the same predicament as goral but with a larger world range, they have fared slightly better and can be found in many mountainous areas in the Kingdom. In a few places they live all the way down to sea level. These goat-antelopes still survive in the Himalayas, northern India, southern China, mainland Southeast Asia and Sumatra. Several subspecies have been recorded and most populations are localized.

Serow have black or dark-gray coarse hair and a long shaggy mane down their backs. Two subspecies of serow are recognized in Thailand: those found in the steep limestone mountains of the south have black legs and those surviving in the Tenasserim range and further north to Burma have rufous colored legs below the knee. Breeding lasts from October to November and a single kid is born after seven months of gestation. Occasionally, twins are born.

Goral – Naemorhedus goral

Goral are found from about 1000 up to 4,000 meters. Their range is from the Himalayas and northern India, to southern China, Burma and northern Thailand. The Thai species are mainly gray-brown in color much like the boulders and rocks that they live around. A thin black stripe runs along their spine to a short tail. As with other wild Asian bovids like gaur and banteng, goral have white stockings from the knee to the hoof. With white patches on their throat and underbelly that stands out in bright sunlight, goral are distinct. They are compact mammals that can move up and down vertical cliffs with ease, and are tough to spot in their habitat. The breeding season lasts from November to December. One or two kids may be born in May or June.