Goats in the Mist: Thailand’s Goat-Antelopes

Goral and Serow – Rare goat-antelopes

Photographing endangered species has become an obsession to me. Many of Thailand’s wild animals have come so close to extinction that their numbers are counted not in thousands or even hundreds but rather handfuls. Goral Naemorhedus goral are one such animal. Surviving on a few scattered mountaintops in northern Thailand, these even-toed ungulates are on the critically endangered list. With fewer than 60 individuals nationwide and low numbers at each site, the goral is considered one of the Kingdom’s rarest mammals.

Goral kid in early morning light at Keiw Mae Pan cliff – Doi Inthanon NP

Acquiring photographs of these goat-antelopes is a daunting task considering their natural habitat. Hunting pressure and encroachment have forced them to retreat to the steepest, most inaccessible limestone cliffs and forested mountains. Goral are still found in seven protected areas including Doi Inthanon and Mae Ping National Parks, and in the wildlife sanctuaries of Om Koi, Doi Luang Chiang Dao, Mae Tuan, Mae Lao-Mae Sae and Lum Nam Pai, all in the north of Thailand.

Another species of goat-antelope surviving in Thailand is the serow Capricornis sumatraenis. Both species belong to the Bovidae family, which includes cattle, sheep, goats and antelope. Bovids are ruminants with four-chambered stomachs. In some areas, goral and serow share the same habitat. They have short bodies with long legs ending in padded, gripping hooves enabling them to inhabit steep mountainsides and cliffs. They eat grasses, herbs and shrubs and gain moisture from the plants they eat. Their keen eyesight provides early warning of danger. Like all bovids, they do not shed their horns like deer do with antlers. Serow are normally solitary whereas goral are usually form small herds from four to twelve individuals.

Male serow caught by camera trap

Serow and goral are creatures of habit. These lofty creatures have favorite places to sun themselves, usually a rock or grassy mound. They can stand for hours on one rock as I witnessed in Doi Inthanon where a goral stood from about 9am to almost 12noon. Another habit is to defecate at the same place. Piles of pellets can be found wherever they live, usually on or around a large rock. Research on both species has now been undertaken by Mahidol and Kasetsart University staff studying the impact of human settlements near goat habitat and surveying the remaining populations.

Unfortunately, both species have been hunted for their meat, horns and oil which comes from boiling the head. Supposedly, the oil is used to relieve arthritis and bone ailments. The horns of goral and serow are black, corrugated at the base, pointed and swept back (like their relatives, the Rocky Mountain goat of North America). Their horns are not impressive but are still sought after by poachers. The tip of serow horn is used to make deadly spears which can be attached to a rooster’s spur during a cock fight. It is eagerly sought after, especially in southern Thailand.

Goral kid close-up

Hunting has decimated both goral and serow populations that numbered in the thousands as recently as 50 years ago. In many mountainous areas hill tribe people live and encroach on the forest for the purpose of slash-and-burn agriculture. This has played a major role in the disappearance of both species in the North. Lowland people also hunted them. In other areas where the serow are found, they have declined due to continued pressure from man.

Two sites were chosen to photograph these mountain creatures: Doi Inthanon National Park about 80 kilometers south of Chiang Mai and Mae Lao-Mae Sae Wildlife Sanctuary some 60 kilometers to the north. Staff at the protected areas confirmed goral and serow were still surviving. Working closely with the Wildlife Research Division in Bangkok. My plan was to set up photographic blinds as close to wild goat domain as possible and use a long telephoto lens. But this was easier said then done.

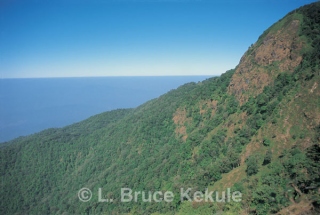

Keiw Mae Pan cliff in Doi Inthanon

Doi Inthanon, Thailand’s highest mountain, supports several small herds of goral around the summit. The animals are quite often seen close to Kew Mae Pan Nature Trail, developed in partnership with the Electric Generating Public Company Limited (EGCO) and the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department (DNP). Three kilometers from the road, a huge cliff rises some 2,500 meters above sea level and is criss-crossed with goat trails etched from thousands of years of use by goral and serow.

The skies are crystal clear over Doi Inthanon in November. This is truly a beautiful and remarkable place. But it does take some effort to get close to the cliff. The nature trail is strictly regulated and a local guide must be used for the three to four hour trek. If you are lucky and get up early, you may see goral and serow sunning themselves on rocky outcrops near the trail. Take a good pair of binoculars or telescope. This is also a good place for birdwatching, and you may see many species including the beautiful endemic green-tailed sunbird.

Doi Inthanon National Park

Mae Lao-Mae Sae is situated along the highway from Chiang Mai to Pai. A part of the sanctuary is divided by the road and Mon Liem, a giant granite massif, rises up to 1,200 meters above sea level. The sanctuary is home to a small herd of goral that survive on the summit. It is also criss-crossed by goat trails, and huge pine trees hundreds of years old are found here. The view is majestic, especially to the north where Doi Luang Chiang Dao Wildlife Sanctuary, another haven for goral, is situated. Wildlife sanctuaries are not open to the general public since they have been set aside for wildlife and biodiversity research. In October 2001, I glimpsed a male goral near the summit as the sun was going down. The goat unfortunately, was out of photographic range.

In November 2001, I visited the superintendent of Doi Inthanon to arrange a photographic trip after both goat species at the cliff. At 2,300 meters above sea level, temperatures can plunge at daybreak to zero degree Celsius with ice forming on the grass. It was tough getting out of the tent at 4 a.m. but it was important to move into the blind near the cliff face before the sun was up in order to photograph these wild goats. For the best photographic opportunities, the blind had to blend into the surrounding terrain so as not to spook the goats.

After four days of freezing, windy conditions, I spotted goral and serow on several occasions about a kilometer away. While scanning the cliff with my binoculars on the last morning, I detected a slight movement. A closer look revealed a male goral lying down on a buff about 500 meters from the blind. A short while later, he stood up. Using my 600mm Minolta lens with 2X tele-converter, I got some acceptable photographs of him.

This male had a fluffy white throat and underbelly. His gray winter coat was beautiful. After some time he did what goral do best – jumping straight down off the ledge in order to get closer to his mate who was feeding below. They butted heads affectionately a few times before disappearing into the maze of the cliff.

I made four trips to Doi Inthanon during the winter of 2001 and 2002 in search of goral and serow. Several herds of goral are still breeding here and can be seen almost every day. Serow are more elusive and only a few individuals were spotted from time to time. The spirits of the mountain listened to my prayers. On the last day of the fourth trip, a young goral about five months old appeared twenty meters away from me stamping its feet and snorting. It was nature at its best, making the front cover of this book.

Siriphum Waterfall in Doi Inthanon National Park

These wild goats have an uncertain future. Uncontrolled human population growth both inside and outside of the protected areas is bound to affect them in the long run. There is also the danger of disease carried by domesticated cattle and buffalo around the mountaintops decimating wild goats – something that needs to be checked and stopped at all costs.

Hunting of goral and serow continues in some areas, and the poachers are rarely brought to justice. Jail terms are too light and outdated. As a result, these animals need serious efforts to protect them from the dangers of the modern world with all the resources available, or they could vanish from the Kingdom’s mountaintops forever. A crime against nature should be on par with a crime against a fellow human being. Enforcement must be improved and implemented on a long term-basis. The Thai community needs more wildlife conservation education at all levels of society.

Serow – Capricornis sumatraenis

Serow share much the same predicament as goral but with a larger world range, they have fared slightly better and can be found in many mountainous areas in the Kingdom. In a few places they live all the way down to sea level. These goat-antelopes still survive in the Himalayas, northern India, southern China, mainland Southeast Asia and Sumatra. Several subspecies have been recorded and most populations are localized.

Serow have black or dark-gray coarse hair and a long shaggy mane down their backs. Two subspecies of serow are recognized in Thailand: those found in the steep limestone mountains of the south have black legs and those surviving in the Tenasserim range and further north to Burma have rufous colored legs below the knee. Breeding lasts from October to November and a single kid is born after seven months of gestation. Occasionally, twins are born.

Goral – Naemorhedus goral

Goral are found from about 1000 up to 4,000 meters. Their range is from the Himalayas and northern India, to southern China, Burma and northern Thailand. The Thai species are mainly gray-brown in color much like the boulders and rocks that they live around. A thin black stripe runs along their spine to a short tail. As with other wild Asian bovids like gaur and banteng, goral have white stockings from the knee to the hoof. With white patches on their throat and underbelly that stands out in bright sunlight, goral are distinct. They are compact mammals that can move up and down vertical cliffs with ease, and are tough to spot in their habitat. The breeding season lasts from November to December. One or two kids may be born in May or June.