Journey through a World Heritage Site: Part Six

Day 7: March 10th – Conclusion: World Heritage in jeopardy

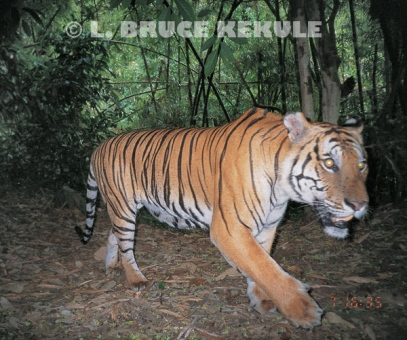

Indochinese tiger at a mineral deposit

After all the dust had settled, I can look back at the situation in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary and honestly make an assessment of how and why this World Heritage Site is in jeopardy.

After hearing about three tigers (mother and her cubs) killed by poisoning, it seems poachers continue to enter this place and kill wild animals in the interior. A serious look at the ranger force and patrolling regimens, and the quality of protection is quickly needed before it is too late.

Deciduous forest abstract

For all the research going on in Huai Kha Khaeng, and the so-called smart patrols, how can poachers kill these rare cats? Other reports that wildlife snares and pipe-guns with trip wires are now found outside the headquarters area in Uthai Thani are alarming. These illegal hunters are slipping through the net so to speak due to too many loopholes in the patrolling and enforcement system.

In India several years ago, two national parks where researchers were working full-time had all their tigers exterminated in a year or so right under their noses. Good patrolling and enforcement is the only option when it comes to protected areas.

Deciduous flowers

Here in Thailand, most of the forest rangers are locals and hence there are not many secrets outside the sanctuary. There are 19 ranger stations that receive money amounting to 1,200 baht cash per patrol for food from the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) who also run the ranger-patrolling program. It would seem that food, clothing and equipment would be better than cash that can possibly go astray.

Approximately two times a month a patrol of five or six men spend a week walking the forests on designated trails. The poachers easily stay out of their way because they know the terrain and continue to do business as usual. It is said a bag of tiger bones now fetches more than a hundred thousand baht. Seems like a great incentive to break the law.

All patrols should originate at the headquarters and nobody knows where they are going or what trail they will take until they are already in the forest to keep leaks to a minimum. Patrol groups should be in the forest 24-7 and continue to revolve so that rangers are always out in the field.

Seub Nakhasathien monument

Without a doubt, new blood in the form of properly trained and sufficiently paid rangers using special-forces techniques is seriously needed in Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai Naresuan next door. Enforcement and arrests of perpetrators should increase and outdated laws up-graded with severe fines and detention, especially for repeat offenders.

Another very important issue is life and health insurance for the rangers in case someone is injured or killed while on duty, and this should be standard for everyone, whether government officer, or permanent and temporary rangers. A central fund should be established for this and in case of a tragedy or accident; the family will be taken care of.

Protection of this World Heritage Site is a number one priority for the government, and everything else should be second. Over the long run, good management, patrolling and enforcement is the only option to save Thailand’s natural heritage for the future.

Journey through a World Heritage Site – Part Five

Day 6: March 9th – Wild pig again, and a herd of banteng and a tuskless bull elephant pose for the camera

After breakfast, I drove a kilometer with a forest ranger in tow to look after me and parked in the forest. I thenwalked for a half hour to Huai Mae Dee, a tributary of the Huai Kha Khaeng. A permanent photo-blind is erected across from a mineral lick, also visited by all the large mammals.

After an hour and slightly down stream, a single wild pig was having a great time wallowing in the mud by the bank in the mid-day heat. After awhile, this female ungulate got closer as I continued to photograph her. It was the first time I had ever seen a female by herself. Mostly, they are in herds and only the large male boars live solitary lives.

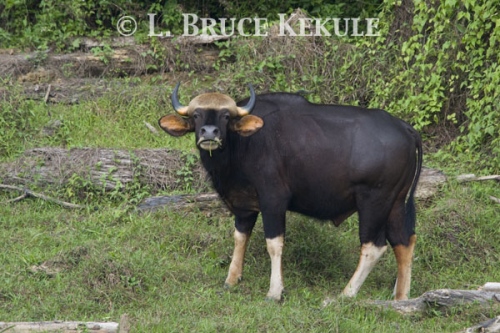

A short time later, a fairly large herd of banteng appeared on a sandbar downstream from the blind. They were just hanging out taking in the sun’s rays and chewing their cud. The cattle then scattered as a huge tuskless bull elephant popped out on the sandbar. He was following a female, probably in heat judging from his actions. The bull did not stay long and actually came up on our side of the river disappearing into the bush, which was a bit unnerving.

At 6pm as darkness fell, our ranger came to help me carry some equipment back actually bumped into the bull elephant but it went crashing off luckily for us. At close quarters, these old cantankerous giants can be extremely dangerous to people and in fact two persons including a ranger and a villager have recently been killed by a tuskless bull in the sanctuary not far from the headquarters. It pays to stay out of their way.

Journey through a World Heritage Site – Part Four

Day 5: March 8th – Waiting on the helicopter

The next morning up at the crack of dawn, I decided to sit in the blind one last time before departing sometime in the afternoon. After an hour, a lone female green peafowl wandered into the mineral lick pecking on the ground for food and coming quite close. A short time later, a little egret also looking for food in the pond was attacked by a changeable hawk-eagle that swooped down from the trees above grabbing and knocking the water bird off its feet. The raptor hung on finally killing the egret. It was all over in a matter of minutes and the bird of prey began feeding.

Finally, the noisy chopper arrived and we piled aboard for the 20- minute ride to the headquarters. Shortly after arriving, we had lunch, and I decided to drive a hundred kilometers south and then west to Khao Ban Dai ranger station that had been our original destination for this trip.

I left after lunch and then stopped at Ban Rai, Uthai Thani for some provisions arriving at the station just as the sun was setting in the west. Dinner was made up of ‘French toast’, a specialty of mine when a quick easy meal is sufficient. Eggs, milk and some whole wheat bread make up the ingredients. The night was cool as I both slept like a log in my hammock.

Journey through a World Heritage Site – Part Three

Day 3: March 7th – Hot trek over the hills

Like clockwork, first light eventually came and after a quick cup of coffee and some breakfast, everyone packed-up their gear and headed out to beat the sun. But it was scorching hot by 10am and the dusty trail went up and down and was long as we threaded our way over the hills on a wildlife trail trodden by elephant and other large animals for millennia.

At lunch, a quick camp was erected down at the river as we all cooled off and enjoyed the refreshing water. An hour later, it was up into the hills again. The rangers attached to me got sidetracked and led us down off trail getting lost for a short period until I headed back up and found the right route. From there, we discovered a pile of gaur bones that had certainly been poached for its horns. Continuing on, we trudged along the path until the late afternoon finally reaching our number one objective as the sun dipped low.

Two large mineral licks situated by the river on either side where large mammals like gaur, banteng and elephant come for the mineral supplements. A set of fresh tiger tracks was discovered on the trail down to the deposit. The rangers quickly set-up a photographic blind in the mineral licks for me as we settled in by the river. Promptly, dinner was served and it was a quick dash to bed for most of the group after the long hot day. The excitement of finally sitting at a mineral lick I had never visited kept me up for awhile as I lay in the hammock.

Day 4: March 8th – Pigeons, parrots, and another wild pig

After that, the day passed slowly and about 4pm, a huge wild boar came to wallow in the mud and take in some vegetation staying for quite sometime. I snapped a long series of photos of the solitary pig. The rest of the day was quiet and we finally retired to the camp just before darkness.

That evening, a decision to cancel the rest of the trip was reached, and to take us by helicopter back to the headquarters due to several issues involving tiger poachers plus the extreme conditions of heat. Three tigers (a mother and two cubs) were found dead from poisoning not to far from our position. Illegal tiger bone hunters were operating in the area and the chief decided to move the group expediently away for our safety as a first priority. In the past, many rangers have been killed or maimed by ruthless poachers. Unfortunately, we would not make our destination down the river but the option to drive there was still open.

Journey through a World Heritage Site – Part Two

On the road to Huai Kha Khaeng

Seub Nakhasatien monument

Day one: March 5th

I left Bangkok slightly behind schedule but made good time as I headed northwest. After five hours of driving with a few pit stops here and there to eat, buy fuel, food and essentials, I arrived at the headquarters of Huai Kha Khaeng. As always, I paid respects to Seub Nakhasatien, a forest ranger who gave his life to nature back in 1990. This site is his spiritual home and many people visit his statue and the house where he lived, in remembrance of his sacrifice. While we were at the headquarters, I photographed a few Eld’s deer that were released into the wild around the station.

Wild boar on the run at a mineral deposit

I then drove another couple of hours going south for a rendezvous at Khao Nang Ram Wildlife Research Station. As I got closer, a huge wild boar flashed across the dirt road and disappeared into the forest giving us a bit of jolt. A total of eight forest guards including the assistant chief graciously welcomed me providing shelter and dinner. I arrived just at dusk and handed over the provisions for the excursion down the river. Dinner was served and we then watched a documentary showing wildlife and tiger research carried out at the station. Everyone retired to bed for an early wake-up.

A racket-tailed drongo by the river

Day two: March 6th – A change of plans

Our original plan was to walk from the research station across the mountains and down to the river but due to extremely hot and dry conditions in the mixed deciduous forest and the possibility of forest fire, it was decided to drive further north to the river and walk from an old deserted ranger station named ‘Yang Dang’ so we would have a good supply of water the entire length of the walk. I brought a water purification pump and we always had clean safe drinking water. This tool was simple to use and carry but extremely important for us city folk accustomed to bottled water.

Through the forest we continued west and arrived at Kabook Kabieng ranger station some 50 kilometers north. During the dry season, this part of the forest in Huai Kha Khaeng is still lush hill-evergreen. For me, this place has many fond memories of great photographic sessions.

Another wild boar at another mineral deposit

I got my first ever camera-trap photograph of a leopard on a deer kill very close to the station. On that same trip, I also photographed another leopard along the road in late afternoon from my truck, and captured a shot of a black leopard from a tree-blind at a nearby hot spring the next day. I got three leopards in two days and it still stands out as one of my great achievements as a wildlife photographer. Leopards are notoriously difficult to see and it was a lucky trip.

A black leopard photographed more than ten years ago at a hot spring

Finally, we all arrived at ‘Yang Dang’ and made preparations for the 30-kilometer trip down river. The road was rough on my old Ford Ranger but we chugged along in low gear for some gut-wrenching 4X4 driving. Unfortunately, a carry rack on top of the cab was ripped off and destroyed during the rough and tumble, and reduced to rubble.

Everyone packed up and off we went down the river. We still had to negotiate about 6 kilometers on foot to the first camp during mid-day temperatures that went past 38 degrees centigrade. It was a struggle but we made it and set-up camp by the peaceful Huai Kha Khaeng waterway just as the sun dipped behind the mountains. The water was extremely cool and it was great having a bath and freshening up for the first night by the river. Dinner was served in typical jungle style with rice cooked in army patrol pots and various Thai dishes including some hot curry. Everyone then hit their beds and sleep quickly overcame the group.

Journey through a World Heritage Site – Part One

Journey through a World Heritage Site: Part One

Hot days, rough terrain and wild pigs galore. Thailand’s last great tiger haven

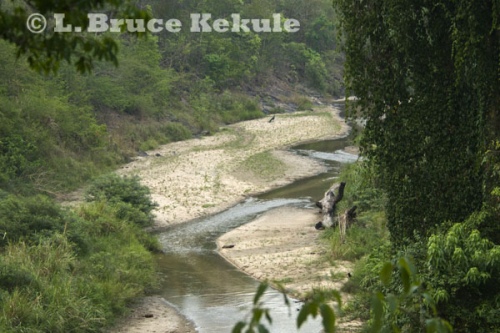

Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary situated in the provinces of Uthai Thani, Tak, Kanchanaburi and Suphan Buri is Thailand’s last great tiger haven. The protected area covers 2,780 square kilometers, and a seasonal river runs through the center of the sanctuary from north to south with many tributaries along its path. During March, the waterway is low but still flowing for most of its length. In some areas however, the sandy river bottom dries up. The weather is very hot during the day with temperatures soaring above 38 degrees centigrade.

Huai Kha Khaeng riverine habitat

An old dream of mine was to walk the river from north to south and experience this majestic animal kingdom first hand. I met with the Director General of the Department of National Parks at the time, Jatuporn Buruspat, to coordinate all logistics for the trip. The plan was to walk from Khao Nang Ram Wildlife Research Station in the eastern section to Khao Ban Dai ranger station in the central part, a distance of about 30 kilometers. It was expected to take about seven days with several stops along the way at a few mineral deposits, hopefully to photograph wildlife.

My trip began on March 5th and left Bangkok first thing in the morning driving some 300 kilometers diagonally across Thailand going northwest. I passed through the very modern city of Suphan Buri with its excellent roads and modern facilities. My final destination is the Huai Kha Khaeng headquarters area situated in the western forests of Uthai Thani province. The deciduous and hill evergreen forest found in the interior still harbor large herds of elephant, gaur, banteng, sambar and wild pig, plus the amazing carnivores, the tiger and leopard in fair numbers. As a World Heritage Site, it truly lives up to its name as Thailand’s top protected area.

Huai Kha Khaeng forest from a helicopter

Huai Kha Khaeng – 7 day walk in a World Heritage Site

Huai Kha Khaeng – 7 day walk in a World Heritage Site – 1st Entry

A new series of trips to Thailand’s top protected areas in 2010

Indochinese Tiger walking through a mineral deposit in Huai Kha Khaeng

This wildlife sanctuary is Thailand’s last great tiger haven. It covers an area of 2700 square kilometers and a seasonal river runs through the middle from north to south. My trip begins on March 5th and I leave Bangkok first thing in the morning driving some 300 kilometers diagonally across Thailand going northwest. I pass the very modern city of Suphan Buri with its excellent roads and modern facilities.

My final destination is the headquarters area situated in the western forests of Uthai Thani province. This deciduous forest still harbor large herds of gaur, banteng and sambar, plus the amazing tiger and leopard in good numbers. Elephants are also quite common in the interior. As a World Heritage Site, it truly lives up to its name as Thailand’s top protected area.

I have been planning this walk for sometime now. Several months ago, I met with the Director General of the Department of National Parks to coordinate all logistics for the trip. The plan to walk from Khao Nang Ram Wildlife Research Station to Khao Ban Dai ranger station, a distance of about 30 kilometers, would take about seven days with several stops along the way at a few mineral deposits.

Nature Photography

Capturing Thailand’s magnificent wildlife on camera

White-bellied sea eagle in Lam Son National Park

Thailand’s breathtaking wildlife and forests has evolved over millions of years into some of the most beautiful and interesting in the world. Photographing these ecosystems and rare animals such as the tiger, leopard, gaur, banteng, wild water buffalo, elephant, Siamese crocodile and tapir, plus a multitude of other mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and insects in their natural habitats is a daunting task to say the least. A multitude of different aspects contribute to the difficult and sometimes dangerous pastime of wildlife photography.

Male green peafowl in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary

Probably the most prominent is the ever-increasing human population growth and social ills like poaching and encroachment in the protected areas. This alone has taken its toll and the country’s wild flora and fauna, from under the sea to the highest mountains, are in serious jeopardy with a slim chance of recovery to the magnificent ecosystems of the past. Present low densities of wildlife depleted over years of intrusion into the forests before any form of protection was implemented is probably the number one reason why so many areas are wiped out and now completely devoid of wild animals.

Pied kingfishers landing on a tree branch in Phetchaburi province

Before World War Two, 75 percent of the nation was still covered in pristine forests. Barely 30 percent survives today and many of these are seriously degraded. Even in 1962 when Khao Yai National Park, Thailand’s first protected area was established, many forests still retained their excellent biodiversity with abundant wildlife and plant species but that quickly changed. Continuing human pressure on the natural resources, and the Asian traditional medicine and black market wildlife trade are directly responsible for a disappearing natural world. Climate change and deforestation has also had a serious affect. Subsequently, wildlife has now become scarce and extremely elusive, and difficult to photograph. With no subjects, it can be a tough assignment to capture wild creatures that were once quite common in their natural habitats. However, not all is lost and the present generation should take a positive interest in preserving what remains of the Kingdom’s natural treasures before it is too late.

Yellow-cheeked tit with a moth in Doi Inthanon National Park

Nature photography is one of the best ways to record and promote wildlife conservation awareness. Wildlife photographs create a mental image that can improve one’s love and understanding of the wonderful world of nature. Many people in the cities have a misconception that Thailand’s wildlife and forests has disappeared into the depths of extinction. This is unfortunate and the populace need constant education and re-education plus media projection to uplift their knowledge that many species and habitats do in fact, still survive.

Spider in early morning sunlight in Chiang Mai province

Knowing where to go with the right equipment is just part of the process. Many other aspects are also important and I hope to pass on some of my experiences to our readers that have a desire to try their hand at nature photography. More and more people have taken-up the game and it has now become quite a popular pastime among the younger generation. Men and women of all ages are now seen with cameras chasing down butterflies to elephants, which is inspiring.

Butterfly in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

Fortunately, some protected areas still remain fairly intact with good densities of flora and fauna. Prey species are abundant and carnivores thrive. These havens for wildlife include time honored Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai Naresuan wildlife sanctuaries, Thailand’s top nature reserve and World Heritage Site. Due to its size (6,427 square kilometers) and biodiversity, this site is absolutely the best Asian wildlife habitat left in the Kingdom.

Sunset in Laem Phak Bia, Phetchaburi province

Kaeng Krachan and Kui Buri national parks further south along the western border with Burma still retain very good ecosystems with a good abundance of creatures including the mighty tiger just waiting to be photographed. Other protected areas worth visiting include: Khao Yai, Thap Lan, Pang Sida, Nam Nao national parks, and Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary in the northeast; Khao Ang Rue Nai and Khao Soi Dow wildlife sanctuaries in the east; Sai Yok, Erawan, Sri Nakarin, Khao Sam Roi Yot national parks, and Umphang and Salak Phra wildlife sanctuaries in the west; Khao Sok, Sri Phangnga national parks, and Khlong Saeng and Khlong Nakha wildlife sanctuaries in the south to mention just a few. There are 14 major forest complexes throughout the Kingdom with over 260 protected areas to choose from.

Asian wild dog by the Phetchaburi River

Thailand’s coastline along the Gulf of Siam extends for 1,840 kilometers, and the Andaman Sea for 1, 037 kilometers, and has hundreds of offshore islands that have birds and mammals but because they are surrounded by water, access by local fisherman has taken its toll. The islands of Tarutao in Satun province and Phi Phi in Krabi are in national parks, and are great photographic havens. Underwater photographing in some places is still excellent.

Pig-tailed macaque in Khao Yai National Park

Worth mentioning are Hala Bala and Budo wildlife sanctuaries and several national parks in the Deep South. However, due to on-going extremist instability in the southern region, it is not recommended to visit these areas until peace returns. This of course is unfortunate as some of these forests are very rich in plant and animal life. When it was quiet, some Thai photographers did record the amazing wildlife here, especially the hornbills.

Burmese striped Squirrel in Kaeng Krachan

Finally, in the north there are a multitude of important mountain forests like Doi Inthanon National Park, Thailand’s highest peak. Others include: Doi Lang, Huai Nam Dang national parks, and Doi Chiang Dao Wildlife Sanctuary in Chiang Mai province plus Nong Bong Khai Non-hunting Area in Chiang Saen, Chiang Rai province. All are great birding sites. In the Central Plains, Bueng Boraphet Non-hunting Area is good for migratory and water birds.

Common crane at Nong Bong Kai Non-hunting Area

Entry into the national parks and non-hunting areas is quite straightforward where permission is obtained at the gate or from the Department of National Parks (DNP) in Bangkok. However, due to the importance of protecting wildlife sanctuaries as natural biospheres, entry is strictly limited and must be obtained from the Wildlife Conservation Division at DNP.

Sunset at Chiang Saen Lake, Chiang Rai province

Wildlife photography is a difficult hobby or profession to become proficient. Years of trial and error, lost shots, bad exposure, out of focus, no wildlife subjects, equipment failure, expense and many other intricate problems make things difficult for the nature photographer. Travel plans and permission to enter the protected areas is a hurdle that must be crossed before any photographs can be taken. But where there is a will, there is a way and the difficult can be overcome.

Goral kid in Doi Inthanon National Park

Being at the right place at the right time with the right equipment using good technique is the secret to capturing wildlife on film and digital. Patience is one of the most important attributes and knowledge of the subject is also very significant. The most important aspect however, is respect for Mother Nature and all her wonderful creatures. No photograph is worth endangering any animal or plant and this should be everyone’s number one priority while in the wilderness.

Kiew Mae Pan cliff in Doi Inthanon

Cameras and lenses in the professional range are expensive but lower-end equipment can also provide very satisfactory results with the right combination, and at a much lower cost. Modern technology like the Digital Single Lens Reflex (D-SLR) is now the ultimate and both Nikon and Canon remain the most popular brands for variety from beginner to professional with cameras, lenses, flash and other equipment.

Banded kingfisher in Khao Yai National Park

Other camera manufacturers such as Sony (Minolta lens mount), Fuji, Pentax, Olympus, Sigma and Leica also offer very good equipment. Aftermarket lenses from Sigma, Tamron and Tokina cost less than the top name brands but also produce very good photographs. Camera brand and model depends on one’s budget, entry level and determination to photograph nature. Second hand camera equipment in good working condition is just another way to lower cost.

Muntjac buck posing in Khao Yai

Birds and mammals usually require a long lens from 300mm to 600mm, but if flowers and insects are the subject, a macro lens in 50mm to 200mm with close focusing capability is the ticket. If panorama landscapes and view shots are on the menu, a wide-angle in 10mm to 28mm lens is perfect in a zoom or fixed configuration.

Bird-eating spider in Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary

The lens is the most important piece of equipment in wildlife photography. The bigger the glass the better the photo quality as it allows more light to pass through, hence a superior picture. Probably the best lens for all round work on mammals and birds is a 400mm f/2.8 from both Nikon and Canon. The front element is 140 mm (5.5 inches) across. They are expensive and quite heavy when a professional body is attached. But where picture quality counts, there is no better lens then this one for wildlife photographers.

Hog deer buck on the run in Phu Khieo

Photographic technique is still very important but the 400mm f/2.8 due to its large aperture and lens really shine in low-light situations that often occur in the forests of Thailand. Other long-range telephoto lenses are the 500mm f/4 and 600mm f/4. Another very good lens is the 300mm f/2.8 with a 1.4 tele-converter for 420mm with a slight drop in f-stop and cost.

Sambar yearling back lit in Phu Khieo

However, all the above lens and camera combinations are heavy and require the use of a tripod and shutter release for tack sharp photos. Zoom lenses in the 70-200mm f/2.8 or the 80-400mm f/4.5-5.6 range also make a good choice for the beginner, casual to serious amateur, or the professional. They are other older manual fixed lenses that work well with a modern D-SLR.

Oriental darter in Phu Khieo

Old-time film (negative and slide transparency) in 35mm and 120mm is still a viable format for wildlife photographers. I know a few people who refuse to jump over to the digital age and they are quite happy shooting film. But most photographers I know now use modern digital cameras due to many reasons, primarily instant feedback of the image and data allowing one to capture great photographs without any delay or chemical processing. Everything is now done on a computer including exposure and retouching to printing one’s images. Digital has made life much easier for the wildlife, bird or nature photographer.

Lesser whistling ducks in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

While in the field during the day, I usually set my camera to Aperture Priority (Auto) at 200-400 ISO and 5.6f-stop for most photographs. I also set my camera with –7 (minus compensation) but will adjust accordingly depending on the situation. An important fact with the modern D-SLR when using a long telephoto lens is the ISO can be adjusted to gain shutter speed equivalent to the length of the lens. As an example: when using a 400mm lens, shutter speed should be at least 400 and above with an appropriate aperture. If the speed is lower, the chances of a blurred image are greater.However, it is possible to get acceptable images at a slower speed with the right technique.

Bull elephant at a waterhole in Khao Ang Rue Nai

In the very early morning or late afternoon, I usually bump the ISO up to 800-1000 and open the aperture to its widest. However, digital noise or grain will be a problem for some cameras at this ISO setting. Experiment in different light conditions and find out what works best for your camera and lens combination. I recently photographed a tiger in very dark conditions in late afternoon with my 400mm set at 2.8f-stop and the ISO at 800. The shutter speed was about 250 but by using a heavy tripod and shutter release cable, I got some amazing images of the big cat as he walked through the mineral lick.

Siamese Fireback pheasant in Khao Ang Rue Nai

Macro or close-up photography is probably the easiest to get started in. Equipment cost is lower and subject matter from insects to flowers is everywhere. It does however take proper technique to get sharp images with good depth of field and lighting. A tripod is very important but when one is impractical, handholding the camera and using a flash can produce excellent images. It can become addictive and I really enjoy shooting the little creatures. I normally keep one of my cameras and macro lens ready, especially when traveling in a protected area.

Phu Khieo enscarpment panorama comprising of four photographs

Landscape photography is challenging and again, equipment cost is lower. A tripod and shutter release is also a must for sharp photos, and a spirit level for a flat horizon. It is now possible to stitch several photographs together in the computer and make a panorama or sweeping wide image. When shooting panoramas, set the camera on manual and take a quick series of shots to keep the exposure consistent. Make sure the tripod head is level and swing from left to right while capturing the scene. Another photographic aspect is abstract in nature. The subject matter is unlimited and only limited by one’s imagination.

Wild water buffalo bull in Huai Kha Khaeng

Proper exposure is critical to shooting excellent images. The camera’s light meter working together with the lens aperture and the shutter determine the finale exposure. However, there are times when the camera needs help to get the best exposure, so you must learn to do that too. Shoot in the RAW file format if possible when using a D-SLR for the best quality image during computer post-processing. Read books and learn about photographic techniques, and how to use computer programs like Photoshop and Lightroom to out-put your nature images.

Great hornbill flying off a fruit tree in Kaeng Krachan

The use of a photo-blind is very important for some species of mammal and bird as most have a circle of fear or certain distance, and they will flee instantly when they see or are disturbed by humans. The blind must be completely sealed off so animals cannot see clear through as any movement in the hide will destroy your chances of getting the shot. One must be absolutely quiet and maintain noise to an absolute minimum.

Indochinese tiger camera-trapped in Kaeng Krachan

Human scent is another problem for wildlife photographers after the large mammals. I usually use gaur or buffalo droppings, when available, and place a plastic bag full of the stuff in front of the blind to cover my scent. It truly works and I have photographed many large animals like elephant, gaur, banteng and wild water buffalo this way. The use of a photo-blind is important as is self-control and patience, which comes with practice and a desire to get a photograph of nature’s creatures.

Rainbow over the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan

Wildlife encounters are usually brief and one must always be ready with camera in hand ready to shoot on a moments’ notice. No two days are alike in the natural world and opportunities must be taken then and there if one is to be a successful wildlife photographer. Finally, share your photographs with as many people as possible. It is the least one can do in order to spread a message that Mother Nature is truly worth saving for the future.

Indochinese tiger in Huai Kha Khaeng

The Indochinese Tiger: Lord of the Jungle

Wild Species Report

Thailand’s mystical cat – A rare striped carnivore and awesome natural predator

Falling leaves signals the dry season has arrived and the forest floor is carpeted with a mosaic of green, yellow, brown, red and orange. A large predator walks the trails seeking its next meal. A barking deer sensing danger barks a warning. The whole community of wild animals is on alert as squirrels and monkeys cry out from the trees above. A striped carnivore stalks a herd of wild pigs. The nervous omnivores squeal and panic, running through the underbrush to escape. But the big cat is quick as lightning – it catches a young pig with sharp claws. The struggle is over in seconds as fangs penetrate to the spine.

Indochinese tiger Panthera tigris corbetti in Huai Kha Khaeng

A tiger has just made a kill. It lifts the lifeless pig into deep cover and devours the carcass. After feeding, the big cat will seek water for a thirst quenching drink. It will lie down and rest until the desire to eat or drink begins again. Tigers sometimes move great distances in search of food. But where there is an abundance of prey, tigers continue to live in balance with nature. The average kill ratio is about twenty unsuccessful attempts to one kill. At a certain time of year, the male tiger will seek out a female in estrus to carry on his legacy.

Some two million years ago, the tiger evolved in Northern China and Siberia, and spread to many parts of Asia all the way to the Caspian Sea and eastern Turkey in the west. The Himalayas stood as a serious barrier to their migrating into India. Some reached Korea and Manchuria, and also advanced south through China then into Indochina, and down to the islands of Sumatra, Java and Bali. Tigers are good swimmers and made it across narrow sea channels. About 10,000 years ago, the big cat moved west through Burma and Bangladesh on to India. At one time, there were probably more than a hundred thousand of them throughout the tiger’s world range.

Tiger on the prowl in late afternoon

A century ago, Thailand was an absolute haven for this carnivore. They could be found in every forest within the Kingdom. But as humanity expanded, the species quickly declined because of human predation, and loss of habitat and prey animals. The pelt is sought after by hunters and its bones wanted by Asian medicine practitioners. Many considered this predator a pest and as modern weapons became available, and humans expanded into the forest, these magnificent beasts really began to vanish. Realistically, it is estimated there might be about 200 to 300 tigers left in Thai forests, which unfortunately, is barely sustainable over the long run in some areas. However, a very few protected areas if properly taken care of, could sustain a population of tigers. Thailand still retains some of the best-protected tiger habitat left in Southeast Asia. Wildlife corridors between protected areas are one of the most important keys to sustainability.

Feral cats caught by camera traps on a wall behind my home

When I began wildlife photography, the burning desire to photograph a tiger in the wild was one of my great wishes. These cats are extremely difficult to see let along photograph. My real first encounter with a tiger was in Sai Yok National Park in western Thailand back in 1996. I was sitting in a tree-blind when one jumped across the stream behind me and I caught a very brief glimpse of the sleek cat as it moved downstream hunting for prey. From that day on I photographed many other wild creatures including the leopard, but never a tiger. I was beginning to doubt whether I would ever photograph one.

My first camera trapped tiger in Sai Yok National Park

Several years later coming back to Sai Yok, I began a camera trap program not far from the headquarters. This was in mid-October 2003. Six traps were set-up in the forest at waterholes and game-trails. As we were breaking camp, the cook asked me for a lucky number. I just lifted my camp chair that left two impressions in the dirt like the numeral 11, and so I called out 11.

My second camera trapped tiger in Sai Yok

A month later, the film and batteries were collected and after processing, I saw two tigers on film. The first was an old male caught at a waterhole on the 11th day of the 11th month that was recorded on the frame. Three days later, a younger male tiger passed another camera up on a 600 meter ridgeline on the 15th at 16.11 pm also imprinted in the frame. Some may say it was just a coincidence to have the number 11 in both photos, but I like to think the ‘spirits of the forest’ had finally answered my prayers.

Tiger camera trapped in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Further south along the Tenasserim Range in Kaeng Krachan National Park at the beginning in January 2001, I began another camera trap program in conjunction with World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF) and the Department of National Parks (DNP) at two locations in the park. The first was along an old logging road not too far from the main gate at Sam Yot. During a four-month period, many animals were captured on film including an amazing six photographs of one mature male tiger. He actually came right up to the camera trap for a facial portrait, and then walked away. That was the beginning of a very successful ‘presence/absence’ program carried out (2001-2004) to determine if tigers and other large mammals were still surviving here.

Tiger male hunting on an old logging road in Kaeng Krachan

The second area was along the Phetchaburi River that flows crystal clear through this magnificent forest. Many tigers walk the elephant trails hunting for prey. My very close friend Sutat Sapphu (a forest ranger with incredible knowledge of this ecosystem) and I began a monthly program setting up more than 20 cameras along the river. One particular individual tiger named ‘four-spots’ due to a marking on its left flank was caught down near a crocodile pond where he actually tried too bite a camera trap and we got a shot of his mouth and whiskers. Over the next few months, ‘4-spots’ was captured up and down the river, and then way up Phanern Thung Mountain at 900 meters by the road into the park at kilometer 28.

Tiger camera trapped on old logging road in Kaeng Krachan

When the road was closed in Kaeng Krachan due to heavy storms and landslides in October 2003, four-spots was consistently camera trapped at kilometers 33, 34 and 35, and down at the infamous ‘KU’ camp by the river. The distance was calculated to be about 22 kilometers apart. Several other male and female tigers were recorded over the three-year program and are a testament to the remarkable biodiversity of Kaeng Krachan. Many other creatures were also caught including tapir, leopard, wild dog, fishing cat, sun bear, the rare Fea’s muntjac, elephant, gaur and serow among others. Returning in November 2008, and now using a digital camera trap, I got a tiger in November at a mineral lick just 12 kilometers from the front gate.

Tiger up-close in Kaeng Krachan

Good things sometimes come our way and I was about to get a reward to coincide with ‘2010-The Year of the Tiger’. The absolute chronology of being at the right place, the right time with the right equipment and the right technique was played out before my eyes. On the 11th of December 2009 (my lucky number again), the tiger in the lead photo and I crossed paths. I was lucky to have been sitting down with my hands on my lap right in front of my camera. If I had been standing, or made just the slightest noise, I would have never seen this old male.

Indochinese tiger on the prowl at night

The trail through dry dipterocarp forest takes about a 40 minute walk to a photographic blind set above a mineral deposit deep in the interior of Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand’s top protected area and World Heritage Site situated in western Thailand. The flimsy structure made of bamboo sits about two meters off the ground and is attached to a tree. Black mesh closes off the cubicle on all four sides that was erected by the park rangers. An opening large enough for a big lens allows a clear view of the waterhole some 50 meters downhill to a saucer shaped depression.

Tiger at night by the Phetchaburi River

This waterhole attracts many creatures such as elephant, gaur, banteng and other ungulates like sambar and wild pig. Tiger, leopard and Asian wild dog also come looking for prey. It is truly a magical place and a tribute to Thailand’s natural biodiversity. Arriving about 12pm, I immediately set-up my cameras and then waited. Feeling dozy, I strung my hammock for a bit of a snooze after the long haul from Bangkok. The afternoon passed-by slowly and about five got up and began a vigil of the mineral lick. A few minutes later decided to actually sit behind my 400mm lens and camera, and do some adjustments to compensate for the fading light. Took a few test shots to make sure the exposure was correct and then waited. Two minutes later, the dream of a lifetime unfolded before me.

Same tiger a month later during the day at the above location

A striped carnivore magically and silently appeared from the forest on my right. The tiger walked straight down to a little stream for a quick drink. The mature male did not linger and continued on his way. However, he did pause briefly to stare up at my position three different times before disappearing into the forest on my left. Total time spent by the cat at the waterhole was less than a minute. I was extremely fortunate to snap 20 frames as the magnificent creature carried on its way. I banged my head against my camera in disbelief to make sure I was not dreaming. After 15 years of wildlife photography, my aspiration to photograph a tiger through the lens has finally come true.

A female tiger in early morning at the same location

The present status of the tiger in Thailand is balancing on the beam of nature. As a World Heritage Site, Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai Naresuan wildlife sanctuaries is the core area and absolutely the last great tiger haven in the Kingdom, and Southeast Asia for that matter due to its size (6,427 square kilometers), and its biodiversity. In Huai Kha Khaeng, the Department of National Parks has really improved the situation with better patrolling, increased help for the rangers, a demarcation fence along the eastern buffer zone in Uthai Thani, constant vigilance by many people and NGOs’ plus improved management, wildlife research and better awareness education. With these measures in place, prey species have come back and are now abundant. Tigers are thriving. There are about a hundred in the Huai Kha Khaeng-Thung Yai block.

Male tiger posing for my camera

Research on the tiger has been carried out by the Wildlife Research Division under the direction of Dr Saksit Simcharoen and his staff in conjunction with several other people and organizations including Dr Ullas Karanth (from India) and Dr Dave Smith from the University of Minnesota.

A waterhole with mineral deposits in Huai Kha Khaeng

Dr Saksit and others has published a paper in the science journal Oryx (How many tigers Panthera tigris in Huai Kha Khaeng: An estimate using photographic capture-recapture samplings) to establish a number. According to Dr Saksit, the home range of the Indochinese subspecies is about 240 square kilometers. Dr Peter Cutter with WWF-Thailand, and also a student with the University of Minnesota, has done his doctorate thesis on ‘tiger’s occupancy monitoring’ using transect and trail sign data gathered in Huai Kha Khaeng.

Tiger entering waterhole

Camera trapping is still by far the best and safest way to establish a home range of a tiger due to its individuality. No two tiger’s striped pattern is alike. It is imperative to use opposing camera traps to get a picture of both sides to identify individuals. Footprint and scat analysis are also very good techniques.

Tiger drinking from shallow stream

In my opinion, collaring a tiger is extremely dangerous as the capture process could possibly injure or impair the animal. As rare as they are, it does not justify losing even one of these magnificent creatures to a possible botched captures and release. Some researchers may not agree but eight tigers in Huai Kha Khaeng have already been collared and ranges determined. You can only get so much data. Loads of tiger home range information has also come from India and elsewhere. I’m all for good passive scientific research (wild animals are not handled at all) carried out to save the tiger.

Tiger looking back at my position

The Western Forest Complex includes 17 protected areas encompassing more than 18,000 square kilometers and has the potential to accommodate 700 tigers. Even though this estimate is high, with good protection and patrolling in all the protected areas in the complex to keep poachers out and encroachment to zero, and to protect the prey species or food chain for the tiger, it is feasible in the future this number could be a reality. However, due to serious fragmentation with roads, dams and reservoirs plus humanity and agriculture, it will be a difficult road ahead unless the present boundaries of the large protected areas stay intact and unharmed, and more corridors set-up through national forests. The World Heritage Site of Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai must be the number one priority of the DNP as a conservation area.

Tiger on the move

For the long run, forest protection and wildlife awareness education to all levels of society is the key to saving the Kingdom’s natural heritage. The government should always strive to use all its resources to keep the forest and wildlife free from the damaging effects of human intervention. The private sector and the government need to be aware of all the problems regarding the forest rangers and try to improve their lives. The forest can be a deadly place to work and these men need incentive, as they put their lives on the line.

Tiger’s final look before disappearing into the forest

Projects to provide food and clothing to help these men are being carried out in a few protected areas by a few individuals, companies and organizations. Without dedicated ranger patrolling, tigers will surely slip away. It is up to the present generation to take proactive measures to make sure Thailand’s wild flora and fauna stays intact for future generations to see, enjoy and cherish.

Ecology and behavior of the Tiger:

To understand how the tiger evolved, we must go back to the beginning of these wild creatures. Nimravidae were the first cats to evolve in the Early Oligocene epoch, about 35 million years ago. They lasted till the Late Miocene, some eight million years ago, when huge grasslands had developed around the world. The large saber-toothed cats were the first of the family Felidae. These long-fanged felines evolved alongside huge herds of grazing mammals like antelope and cattle. There were several different species of saber-tooth, but they all became extinct about two or three million years ago.

Modern cats belong to the family Felidae which includes: tiger, lion, leopard, cheetah, and domestic cats. Ultimate carnivores, they feed almost exclusively on vertebrate prey and sit at the top of the food chain. Wild cats have few predators apart from man. The tiger belongs to the genus Panthera or roaring cats that also includes the lion, leopard and jaguar.

Tiger camera trapped abstract

The Indochinese tiger Panthera tigris corbetti was named after Jim Corbett, the famous conservationist and hunter of man-eating tigers and leopards in India during the 1930s’. This subspecies is found in Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, eastern Burma and southeastern China. According to Chatchawan Pisdamkham, Director of the Wildlife Conservation Division of the DNP, there are approximately 250-300 tigers left in the wild of Thailand.

The following protected areas still harbor these magnificent felids: Huai Kha Khaeng, Thung Yai Naresuan, Umphang and Salak Phra wildlife sanctuaries plus Mae Wong, Sai Yok, Sir Nakarin, Erawan, Kaeng Krachan and Kui Buri national parks in the west; Khao Yai, Thap Lan and Pang Sida national parks, and Phu Khieo wildlife sanctuary in the Northeast, and Hala Bala Wildlife Sanctuary in the deep south.

Tiger camera trap abstract

It is doubtful if any tigers survive in the protected areas of the north or Khlong Saeng-Khao Sok forest complex in the south as no reports have come from these areas for many years. Eastern Thailand has no tigers on record. A couple of years back, the newspapers reported on tiger tracks found not far from the road around several national parks in Chiang Mai and Lampang but were fake put down by a prankster to stir-up media frenzy. This was supposedly to help villagers who had lost cattle to a predator, more likely feral dogs.

Tigers are essentially solitary but come together when a female is in estrus. The resident male will copulate with a female many times over several days. Gestation ranges from 93-114 days. Litters can be from one to seven but usually only two to three cubs survive. Tigresses rarely accompany more than three cubs in the wild and abundant prey is required for a growing family with a small home range about 60 square kilometers.

Indochinese tiger tracks in Kaeng Krachan

It has highly developed vision about six-times more powerful than man and an extreme sense of hearing. These attributes are essential in locating prey. The feed almost exclusively on herbivores and are at the top of the food chain.

Indochinese tiger habitat in Kaeng Krachan

The tiger’s ultimate advantage in stalking prey is its striped pattern that is natural camouflage and this cat is a very efficient killer. It has awesome strength and unmatched armament of retractable claws, long fangs and dagger-like canines. It can sometime dispatch animals as large as gaur, wild water buffalo and small elephants. Tigers have no predators other than humans.

Gaur – Majestic Wild Forest Ox

WILD SPECIES REPORT

Rare mammal and the largest bovid in the world

Endangered wild cattle close to extinction

Gaur cow in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

About 20 million years ago, the first ungulates evolved from small, hornless deer-like ancestors. Cattle, sheep, antelopes and goats are grouped together in the family Bovidae, and the most common hoofed grazing animal seen today. Sometime during the Pleistocene Epoch 1.8 million years ago, the genus Bos evolved in Asia and spread to Europe, Africa and eventually North America. Gaur Bos gaurus is a descendent of Bos Bibos, a wild cattle that lived on the great plains of Asia. Saber-toothed cats were one of the top carnivores at the time, and evolved alongside the ancient herbivores.

Gaur calf in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

Gaur, the largest bovid in the world, is threatened with extinction and deserves much greater attention. The tiger and elephant have taken most of the conservation spotlight but gaur, like all the other wild animals need just as much protection, research and concern. Unfortunately, these wild forest ox continue to vanish from the wilderness areas in the Kingdom. After years of poor protective management and neglect, poaching and trophy hunting, plus a disappearing habitat suitable for these enormous creatures once found throughout Thailand, is the main reason for the decline.

Over their entire range, they are classified as internationally threatened. But not all is lost as gaur still survive quite well in a few of Thailand’s top protected areas in fair numbers, and where there are true safe havens, the species has actually made a come back. It is now estimated that more than a 1,000 individuals remain in Thai forests. This number is up from the 500 recorded in Dr Boonsong Legakul and Jeffery McNeeley’s book Mammals of Thailand published in 1977. Dr Sompoad Srikosamatara and Varavudh Suteethorn published a paper in the Siam Society’s Natural History Bulletin in 1995 about gaur and banteng. Their estimate then was about 1000 gaur were surviving so the number is basically stable and most likely on the increase.

Gaur herd at a mineral deposit in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary

In Southeast Asia and India, gaur is found in scattered and splintered habitats. Other large wild bovine are banteng and wild water buffalo of Southeast and Southern Asia, the yak of Central Asia, the cape buffalo of Africa, and the bison of North America and Europe. In recent times, the number of these wild creatures has dwindled as humans continue to hunt them for meat and trophies, and destroy and encroach on their habitat in some places. The American bison came close to extinction but was saved in the nick of time. Thousands of wild bison now survive due to conservation efforts initiated by many people including the late U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt.

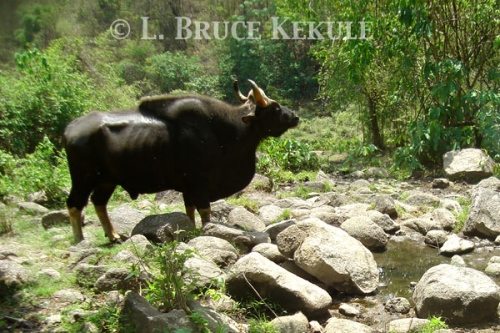

Gaur is Thailand’s second largest terrestrial animal after the elephant and tends to inhibit deep mountainous terrain far from humans. They survive in dry and moist evergreen forest plus mixed deciduous forests and therefore, have fared better than their cousin, the banteng that live in more open lowland forest. Gaur occasionally mixes with banteng that has been documented in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, Uthai Thani province. Gaur will also shadow elephant herds using the same trails made by the larger mammals.

Gaur herd in Khlong Saeng

My favorite photographic wildlife subject is gaur. In Thailand, these majestic ungulates can still be found in the following places: the Western Forest Complex and Kaeng Krachan Forest Complex, both in the west; the Khao Ang Rue Nai Forest Complex in the east; the Dong Payayen – Khao Yai Forest Complex and the Phu Khieo – Nam Nao Forest Complex, both in the Northeast; and down south in the Khlong Saeng – Khao Sok Forest Complex. Due to the serious instability in the deep south, very few surveys have been carried out and there is no consensus on gaur but they do survive in the Hala-Bala Forest Complex situated along the border with Malaysia. It is doubtful if any gaur survive in the North but the Omkoi – Mae Tuen Forest Complex might have few left.

Gaur has a keen sense of smell and hearing, and is always alert for danger. As a result, they can be tough to spot in the dense forests of Asia. However, luck does come sometimes, and the following accounts describe the few times I have had the great fortune to observe these magnificent beasts in the wild.

Gaur bull camera-trapped at a mineral lick in Huai Kha Khaeng

My first photographic encounter with gaur in 1986 was at the beginning of my career as a wildlife photographer deep in the interior of Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. A natural deposit or mineral lick several hours walk from the road attracts many animals – gaur, banteng, elephant, sambar and muntjac come for the life-giving minerals, plus tiger, leopard and Asian wild dog hunt for prey. The balance of nature runs in harmony where “eat or be eaten” is the rule. I was extremely lucky and photographed two mature bull gaur that arrived late one afternoon as the sun was setting. The old bull on the front cover of my first book ‘Wildlife in the Kingdom of Thailand’ stayed at the waterhole for quite sometime and I shot several rolls of film. This place has always been special to me.

A year later, I began visiting Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary along the western border with Burma specifically to photograph gaur. In 1985, a herd of more than 50 individuals was seen from a helicopter by park officials on the huge grassland in the center of the sanctuary. Thung Yai is a tough place to work as many mining trucks plus off-road 4X4 enthusiasts with big tires and jacked-up truck chassis have abused the road into the sanctuary for many years. Deep ruts in many areas make travel along the road difficult even for normal off-road vehicles. The rangers have a real rough time patrolling this sanctuary.

Young gaur bull in Khlong Saeng

On one of my many trips to Thung Yai, and after many grueling hours of travel, and then a couple hours’ walk to a mineral lick in the sanctuary, I set-up a photographic blind along the forest perimeter. Late in the afternoon, two bachelor bulls entered and drank from the spring at the top end. I managed to get some good photographs as they went about their business. One bull snorted at our position as I had placed fresh gaur droppings in front of the blind, and I believe he was just letting us know who he was. Both bulls then departed peacefully and I was elated to say the least. It is estimated that more than 100 individuals thrive in Thung Yai.

In October 2008, I began a camera-trap program and set several units at a mineral lick visited by gaur and elephant in Kaeng Krachan National Park in Phetchaburi province, southwest Thailand. A month later, I visited the park and collected the cameras. A herd of gaur had come to the deposit including several cows and their offspring. It seemed as if the camera had spooked them initially, but the herd came back again the next day and a long series of captures was obtained. There are about 70 of these beautiful creatures thriving and breeding in this protected area.

Over in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in the west during December 2008, I also set some digital camera-traps at a water hole, and after one month, two gaur bulls visited the waterhole. I also sat by the river in a photo-blind across from another mineral lick and photographed a large herd of gaur that had come for the minerals and lush grass. It is estimated that 350 gaur survive in this sanctuary. Better protective measures have allowed gaur to breed profusely and this World Heritage Site lives up to its name. Predators like tiger and wild dogs capable of taking on gaur, also thrive here. In the whole of the Western Forest Complex, it is estimated that more than 500 individuals live in scattered areas covering some 15,000 square kilometers.

Gaur cow camera-trapped at a mineral lick in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Early this year while photographing wildlife in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Surat Thani province down south, I had an amazing journey of discovery. Deep in the protected area, gaur is still thriving quite well. I set camera-traps in the sanctuary and managed to capture a very old bull gaur and several herds at many locations. A close look at the photograph shows seriously worn hooves on his hind feet. He is definitely past his prime and would not be a contender for female gaur in heat. With poor traction, he could not fight the younger bulls with stronger hooves and horns.

I also toured the flooded forests of Khlong Saeng and Khlong Ya rivers created by the Chiew Larn or Ratchaprapra Dam using a boat-blind and silent electric trolling motor. I was able to approach many herds and individuals over a four-month period. In every herd, there were young calves and yearlings indicating a healthy breeding population. Most of the mature bulls have become nocturnal due to past and present poaching pressure in the reservoir. In the Khlong Saeng – Khao Sok forest complex, it is estimated that more than 100 gaur are thriving.

In Kui Buri National Park, Prachuap Kirikan province, gaur has definitely made a come back due to increased awareness by the park staff plus financial support extended to help the rangers. It is now estimated that the population of gaur is about 70 individuals. Khun Chalerm Yoovidhya, MD of the Huai Hin Hills Vineyard and Siam Winery has taken a special interest in gaur at Kui Buri. Working with the park officials, he has funded many projects to help these creatures by sending volunteers to plant grass in selected areas to propagate grasslands, and setting up salt licks and check dams to attract the herbivores. Other projects initiated by Khun Chalerm include selling wildlife photographs and paintings at the vineyard to help the park rangers with food, clothing and equipment giving them more incentive to patrol the forest. Over time, other areas will put on the list for special help to protect Thailand’s natural heritage from the damaging effect of human poaching and intervention.

Gaur spooked by camera-trap in Kaeng Krachan

In the northwest section of Thap Lan National Park, my very close friend Gate Glomchum who worked for the Petroleum Authority of Thailand (PTT) as chief reforestation officer (retired) did some amazing things during his career as a reforester. Prior to 1996, a 10,000 rai area in Wang Nam Kheaw was completed degraded by a logging concession and squatters. Under his management and following a mandate set by His Majesty the King, this forest was replanted and the people were moved out. Today, this forest has completely grown-over, and there is elephant, gaur and tiger plus many other classic Asian species living in total harmony with nature. Other areas in Thailand also reforested under his supervision have had similar success.

Over in Khao Phang Ma just outside the eastern part of Khao Yai National Park, a national forest reserve was reforested by Wildlife Fund Thailand (WFT) and Khun Suthirat Yoovidhya (Director of CSR) of Red Bull-Thailand fame. Gaur moved back into this forest from Khao Yai after protective measures increased. There are about 50 gaur at this location and is probably the only place in Thailand where gaur live outside a protected area. Many projects like helping the rangers, setting-up salt licks and check dams have also been funded by Khun Suthirat under the ‘Red Bull Spirit’ program that is on-going. A couple of years ago, WFT shutdown all conservation operations due to internal conflicts but the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP) took over responsibility of the reserve. They should be commended, and it is reassuring that some people are serious about conserving the Kingdom’s natural heritage.

Gaur herd camera-trapped at a mineral lick in Kaeng Krachan

In the long run, the importance of protecting a prey species like gaur should be the number one priority for the government. The DNP need to increase budgets and personnel to look after these forests and animals. Thailand remains one of the best places for the survival of gaur in Southeast Asia. Protection, conservation awareness, education and monetary support are the keys to the future of these magnificent creatures of nature, and it is hoped they will continue to live in their natural habitat far from the destructive forces of man.

Ecology and Behavior

Gaur is the largest bovid in the world with a distinctive dorsal ridge and a large dewlap, forming a very powerful appearance. A fully mature bull stands about 1.6-1.9 meters at the shoulder and average weight of a big bull is 900 kilograms on up to a ton. Cows are only about 10cm shorter in height, but are more lightly built and weigh 150 kilograms less. These even-toed ungulates have stout limbs with white or yellow stockings from the knee to the hoof. The tail is long and the tip is tufted. Newborns are a light golden color, but soon darken to coffee or reddish brown. Old bulls and cows are jet black but south of the Istamas of Kra, many take on a reddish hue.

All bovine share common features, such as strong defensive horns that never shed on males and females, as well as teeth and four-chambered stomachs adapted for chewing and digesting grass. Their long legs and two-toed feet are designed for fast running and agile leaping to escape predators. They are gregarious animals, staying in herds of six to 20, or more.

Due to their formidable size and power, gaur has few natural enemies. Leopards and Asian wild dog packs occasionally attack unguarded calves or unhealthy animals, but only the tiger has been reported to kill a full-grown adult. Gaur grazes on grass but also browse edible shrubs, leaves and fallen fruit, and usually feed through the night. They also visit mineral licks to supplement their diet. During the day, they will rest-up in deep shade.

There are three separate sub-species of gaur: Bos gaurus gaurus of India and Nepal, Bos gaurus readi of Indochina and Bos gaurus hubbacki of Southern Thailand and Malaysia. However, in 1983, the zoological classification of both the Indochinese and Southern gaur was changed to Bos gaurus laosiensis. In 1993, Pleistocene fossil evidence of Bos gaurus grangeri, an ancient sub-species, was uncovered by G.B. Corbet and J.E. Hill in Sichuan province, China.