Wildlife Candid Camera-Update: Photographing rare creatures with modern digital wizardry

Trail cameras catch Thailand’s cryptic wildlife

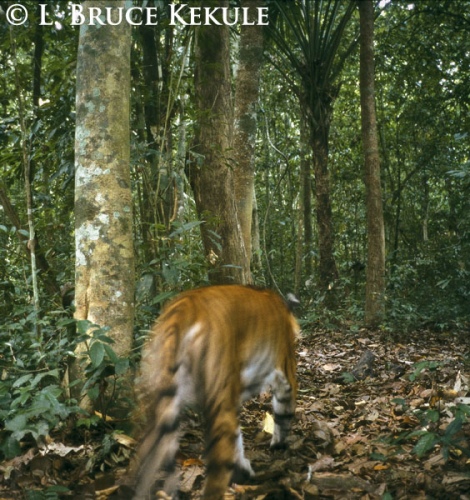

Indochinese tiger camera trap abstract

Camera trapping has been around for over a century when George Shiras III making history used the first flashlight camera triggered by trips wires in 1906. In the late twenties, two other men, F.M. Chapman and F.W. Champion, used pressure plates to activate their cameras. National Geographic and other magazines published many photographs from these early pioneers’ work.

In the 1970s, the first commercial camera trap was produced by TrailMaster.com using ‘active infrared’ to control the cameras followed by CamTrakker.com that used ‘passive infrared’ controlled traps to set off their cameras. Both companies incorporated simple point-and-shoot film cameras from Olympus and Yashica to capture photographs of wildlife.

Asiatic sun bear in Kaeng Krachan

Active infrared uses a beam between two separate units (transmitter and receiver hooked to a camera) and when the beam is broken, the camera is tripped. One the other hand, passive infrared detects motion within a given area covered by the sensor and will trip the camera when movement is detected (much like the sensors above automated doors in shopping malls and convenience stores). Both systems have merit and used in the right situation work equally well.

These first early-production units were designed and used by hunters in America to scout areas for deer, turkey and bear prior to hunting season. This in turn helped them to indentify trophy animals and movements of game in a given forest.

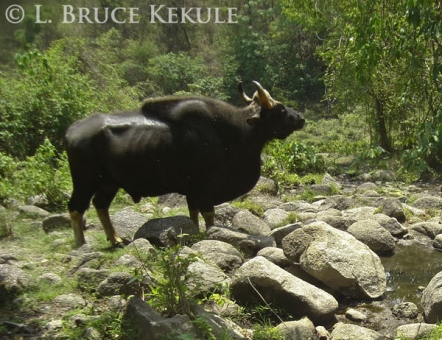

Gaur bull at a waterhole in Huai Kha Khaeng

It was not long before wildlife researchers found camera traps could also benefit their work with a photograph, plus the time and date, allowing them to create an extensive database of the animals living is a certain area. Behavior, presence/absence and other aspects of mammals, birds and reptiles are recorded.

Gaur cow at a mineral deposit in Kaeng Krachan

Wildlife photographers have also used camera traps to capture images of rare, endangered or cryptic creatures. Some have used simple camera-traps but others have incorporated high-end SLR or DSLR cameras with several flashes.

Banteng bull and forest flies in Huai Kha Khaeng

Steve Winter with National Geographic Magazine got an amazing photo of a snow leopard using a Canon DSLR and three Nikon flashes that won the Wildlife Photographer of the Year contest in 2008. The following year, a camera trap photograph of a wolf jumping over a fence won first prize but was later disqualified as the carnivore was domesticated and trained to jump. The organizers of this prestigious event should put camera trapping into its own category.

Banteng cows at a waterhole in Huai Kha Khaeng

The homebrew ‘Game Cam’ or ‘Trail Cam’ as it is now known by its users in the U.S.A. is a unique device with some units very high tech in its features, yet simple to operate and enjoy for just about anyone that has an interest in capturing photographs of wildlife.

Wild water buffalo caught by the Huai Kha Khaeng

The popularity of these cameras has grown at a fast pace over the last few years and opened up a number of usage possibilities to the users. There is also a huge ‘home-brew’ market for the do-it-yourself enthusiast plus the ready-made models that are available for those with a larger budget and no time to build one.

Serow in Sai Yok reserved forest

Camera traps have become very sophisticated and most now use some form of digital camera incorporated into the housing. There are now many companies producing them for less than one hundred U.S. dollars up to $900 or more. Some are fair and some quite good but many are not suitable for the tough conditions found in Thailand’s forests, especially the lower cost models.

Sambar stag in Khlong Saeng

As a wildlife photographer and due to the high cost of buying and importing commercial models into Thailand, I decided to produce my own camera traps. In the beginning, I used passive infrared circuit boards obtained from ‘Radio Shack’ in the U.S and had my close friend Yutdhana Anantavara from Chiang Mai, an electrician working offshore in the Gulf of Thailand, to hook-up the delicate electronics and modify some simple ‘point and shoot’ film cameras (Olympus and Canon).

To stand-up to the rigorous conditions in a Thai forest where moisture, invading insects and elephants can destroy plastic bodied camera traps, I designed and built the housings from aluminum at my machine shop in Chiang Mai.

Buffy fish-owl landing by the Phetchaburi River

A local welder TIG welded-up the box and I machined it flat. By using silicon sealant available at most hardware stores between the box and the flat faceplate, and by using large 10mm machine screws to get a tight seal, sealing is 100 percent. These have defeated many inquisitive elephants.

A small bag of silica gel (desiccant) is inserted in the box to protect the delicate circuit boards, cameras and film from moisture. I tested them on feral cats that walked on a wall at the back of my shop with some good results. These early models worked very well and I then decided to deploy them in the forest.

Feral cat camera-trapped behind my shop in Chiang Mai

In mid-2003, I set six camera traps in Sai Yok National Park in western Thailand by wildlife trails and waterholes. Every month, I would visit the traps and change film, batteries and desiccant. After four months, I finally got my first tiger, and then a second cat a few days later up on a 600-meter ridgeline. All the hard work and expense finally paid off.

It was the beginning of a program to catch the tiger on film. Other animals caught in Sai Yok were elephant, sambar, barking deer, wild dog, wild pig, serow and stumped-tailed macaque. I even managed to catch a water monitor on one camera.

Indochinese tiger by the Phetchaburi River

Even some poachers and hunting dogs were captured on film. One of those original film cameras is still working in the field and I named it ‘Tiger Cam’ as it caught my second tiger.

I then moved down to Kaeng Krachan National Park in the Southwest where I spent three years camera trapping wildlife to establish a presence/absence program in conjunction with Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF-Thailand provided funding), and the Department of National Parks granted permission.

Gaur cow and calves in a mineral deposit in Kaeng Krachan

At that time, many tigers and leopards plus loads of prey species were thriving by the Phetchaburi River and a few of its tributaries, and many photographs were obtained over the course of the survey indicating a healthy ecosystem. Both prey and predator were living in natural harmony. I shut down the program after poachers stole three units near the headwaters of the river that was both costly and disappointing.

Sometime in 2007, my good friend Chris Wemmer, the Camera Trap Codger, who is now retired from the Smithsonian Institute, was the first person to tell me about a new company in the US producing infrared circuit boards and other accessories for the home-brew digital camera trap market. The company is Pixcontroller.com. Unfortunately, they no longer offer parts but now sell complete units with digital camera and video.

Asian wild dogs by the Phetchaburi River

A quick look on the Internet, and several companies offering boards and components to build ‘homebrew’ trail cameras are on-line. The best and the most reliable are boards from Snapshotsniper.com and Yeticam.com. The list for complete units is long and is best searched on the web.

I finally purchased some of the new high-tech boards and made-up some new traps using Sony ‘point-and-shoot’ digital cameras. These were modified by EDI, a company based in Bangkok to work with the electronic boards. The aluminum cases remained the same as the early production units as the best option for durability, and against moisture and elephants.

Tusker camera trapped at a waterhole in Huai Kha Khaeng

The first units were set-up at several mineral deposits deep in the forest of Kaeng Krachan National Park over a three-month period from October to December 2008. Animals digitally captured were tiger, elephant, gaur, sambar and muntjac. One camera had over 300 captures in one month at a mineral lick of elephant and gaur.

I then moved down to Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Surat Thani, southern Thailand and in the first part of 2009, began a new program setting both film and digital camera traps deep in the interior. Elephants, gaur, tapir, wild pig, sambar, muntjac, golden cat and Argus pheasant were captured.

Giraffe caught in Samburu Game Reserve in Kenya, Africa

This year in September, I made a trip to Kenya, Africa and took two camera traps with me. Due to the strict regulations about exiting the safari vehicle, it was difficult to set them up. But at one location, I was able to install one by a game trail. In four hours, a giraffe and elephant passed the camera. It showed how well these cameras can record passing wildlife, and the giraffe photograph shown in the story is the best one.

LBK camera trap using Sony W7 with a ‘Yeticam.com’ infrared board

in aluminum case with ‘Python’ locking cable

I now have more than a dozen digital camera traps using primarily ‘Sony S600 and W7’ cameras. They have been the best and most durable due to the manual features like ISO and f-stop adjustments, and compatibility with the infrared boards. Picture quality with the ‘Carl Zeiss’ lens is very good in the daytime and quite good at night.

The latest craze for camera trappers is ‘infrared capture’. The photos however are a greenish black and white, but are quite good for identification and scientific work. This system is unseen by animals and reported not to disturb them as a conventional flash.

Poachers and dog camera trapped in Sai Yok National Park

Video is another option. I now have two ‘Sony Handy Cams’ set-up with ‘Lanc’ video infrared boards that work very well. One is for daytime only and the other set to ‘night-shot’ with an infrared filter over the video light. Both work together at the same location over the course of a month between battery changes and downloads. It is just another option for those needing wildlife images, whether stills or movie.

The modern digital camera trap has allowed me to capture/recapture many rare and cryptic creatures on their own time, and in their own habitat. As wild animals continue to disappear, more protection, research and understanding are needed to save the natural world.

It is my main priority in life to educate all levels of society on what the Thai nation still has in regards to wildlife and the protected areas, and the need for proactive response to all the dangers facing Mother Nature. We must act fast to illuminate these threats to the Kingdom’s natural world so present and future generations can see, enjoy and cherish this wonderful heritage.