The Indochinese Tiger: Lord of the Jungle

Wild Species Report

Thailand’s mystical cat – A rare striped carnivore and awesome natural predator

Falling leaves signals the dry season has arrived and the forest floor is carpeted with a mosaic of green, yellow, brown, red and orange. A large predator walks the trails seeking its next meal. A barking deer sensing danger barks a warning. The whole community of wild animals is on alert as squirrels and monkeys cry out from the trees above. A striped carnivore stalks a herd of wild pigs. The nervous omnivores squeal and panic, running through the underbrush to escape. But the big cat is quick as lightning – it catches a young pig with sharp claws. The struggle is over in seconds as fangs penetrate to the spine.

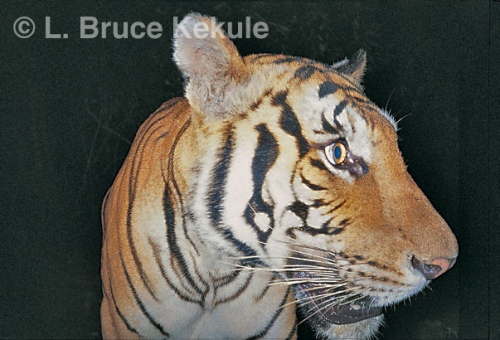

Indochinese tiger Panthera tigris corbetti in Huai Kha Khaeng

A tiger has just made a kill. It lifts the lifeless pig into deep cover and devours the carcass. After feeding, the big cat will seek water for a thirst quenching drink. It will lie down and rest until the desire to eat or drink begins again. Tigers sometimes move great distances in search of food. But where there is an abundance of prey, tigers continue to live in balance with nature. The average kill ratio is about twenty unsuccessful attempts to one kill. At a certain time of year, the male tiger will seek out a female in estrus to carry on his legacy.

Some two million years ago, the tiger evolved in Northern China and Siberia, and spread to many parts of Asia all the way to the Caspian Sea and eastern Turkey in the west. The Himalayas stood as a serious barrier to their migrating into India. Some reached Korea and Manchuria, and also advanced south through China then into Indochina, and down to the islands of Sumatra, Java and Bali. Tigers are good swimmers and made it across narrow sea channels. About 10,000 years ago, the big cat moved west through Burma and Bangladesh on to India. At one time, there were probably more than a hundred thousand of them throughout the tiger’s world range.

Tiger on the prowl in late afternoon

A century ago, Thailand was an absolute haven for this carnivore. They could be found in every forest within the Kingdom. But as humanity expanded, the species quickly declined because of human predation, and loss of habitat and prey animals. The pelt is sought after by hunters and its bones wanted by Asian medicine practitioners. Many considered this predator a pest and as modern weapons became available, and humans expanded into the forest, these magnificent beasts really began to vanish. Realistically, it is estimated there might be about 200 to 300 tigers left in Thai forests, which unfortunately, is barely sustainable over the long run in some areas. However, a very few protected areas if properly taken care of, could sustain a population of tigers. Thailand still retains some of the best-protected tiger habitat left in Southeast Asia. Wildlife corridors between protected areas are one of the most important keys to sustainability.

Feral cats caught by camera traps on a wall behind my home

When I began wildlife photography, the burning desire to photograph a tiger in the wild was one of my great wishes. These cats are extremely difficult to see let along photograph. My real first encounter with a tiger was in Sai Yok National Park in western Thailand back in 1996. I was sitting in a tree-blind when one jumped across the stream behind me and I caught a very brief glimpse of the sleek cat as it moved downstream hunting for prey. From that day on I photographed many other wild creatures including the leopard, but never a tiger. I was beginning to doubt whether I would ever photograph one.

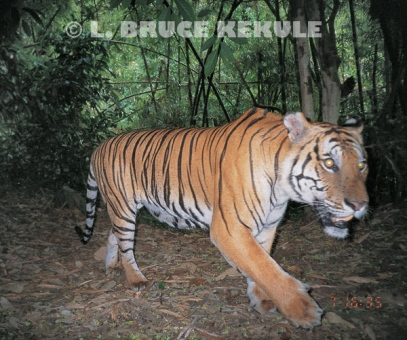

My first camera trapped tiger in Sai Yok National Park

Several years later coming back to Sai Yok, I began a camera trap program not far from the headquarters. This was in mid-October 2003. Six traps were set-up in the forest at waterholes and game-trails. As we were breaking camp, the cook asked me for a lucky number. I just lifted my camp chair that left two impressions in the dirt like the numeral 11, and so I called out 11.

My second camera trapped tiger in Sai Yok

A month later, the film and batteries were collected and after processing, I saw two tigers on film. The first was an old male caught at a waterhole on the 11th day of the 11th month that was recorded on the frame. Three days later, a younger male tiger passed another camera up on a 600 meter ridgeline on the 15th at 16.11 pm also imprinted in the frame. Some may say it was just a coincidence to have the number 11 in both photos, but I like to think the ‘spirits of the forest’ had finally answered my prayers.

Tiger camera trapped in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Further south along the Tenasserim Range in Kaeng Krachan National Park at the beginning in January 2001, I began another camera trap program in conjunction with World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF) and the Department of National Parks (DNP) at two locations in the park. The first was along an old logging road not too far from the main gate at Sam Yot. During a four-month period, many animals were captured on film including an amazing six photographs of one mature male tiger. He actually came right up to the camera trap for a facial portrait, and then walked away. That was the beginning of a very successful ‘presence/absence’ program carried out (2001-2004) to determine if tigers and other large mammals were still surviving here.

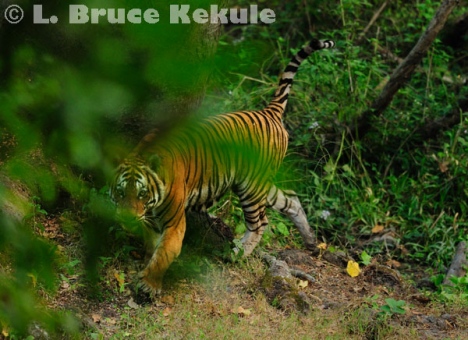

Tiger male hunting on an old logging road in Kaeng Krachan

The second area was along the Phetchaburi River that flows crystal clear through this magnificent forest. Many tigers walk the elephant trails hunting for prey. My very close friend Sutat Sapphu (a forest ranger with incredible knowledge of this ecosystem) and I began a monthly program setting up more than 20 cameras along the river. One particular individual tiger named ‘four-spots’ due to a marking on its left flank was caught down near a crocodile pond where he actually tried too bite a camera trap and we got a shot of his mouth and whiskers. Over the next few months, ‘4-spots’ was captured up and down the river, and then way up Phanern Thung Mountain at 900 meters by the road into the park at kilometer 28.

Tiger camera trapped on old logging road in Kaeng Krachan

When the road was closed in Kaeng Krachan due to heavy storms and landslides in October 2003, four-spots was consistently camera trapped at kilometers 33, 34 and 35, and down at the infamous ‘KU’ camp by the river. The distance was calculated to be about 22 kilometers apart. Several other male and female tigers were recorded over the three-year program and are a testament to the remarkable biodiversity of Kaeng Krachan. Many other creatures were also caught including tapir, leopard, wild dog, fishing cat, sun bear, the rare Fea’s muntjac, elephant, gaur and serow among others. Returning in November 2008, and now using a digital camera trap, I got a tiger in November at a mineral lick just 12 kilometers from the front gate.

Tiger up-close in Kaeng Krachan

Good things sometimes come our way and I was about to get a reward to coincide with ‘2010-The Year of the Tiger’. The absolute chronology of being at the right place, the right time with the right equipment and the right technique was played out before my eyes. On the 11th of December 2009 (my lucky number again), the tiger in the lead photo and I crossed paths. I was lucky to have been sitting down with my hands on my lap right in front of my camera. If I had been standing, or made just the slightest noise, I would have never seen this old male.

Indochinese tiger on the prowl at night

The trail through dry dipterocarp forest takes about a 40 minute walk to a photographic blind set above a mineral deposit deep in the interior of Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand’s top protected area and World Heritage Site situated in western Thailand. The flimsy structure made of bamboo sits about two meters off the ground and is attached to a tree. Black mesh closes off the cubicle on all four sides that was erected by the park rangers. An opening large enough for a big lens allows a clear view of the waterhole some 50 meters downhill to a saucer shaped depression.

Tiger at night by the Phetchaburi River

This waterhole attracts many creatures such as elephant, gaur, banteng and other ungulates like sambar and wild pig. Tiger, leopard and Asian wild dog also come looking for prey. It is truly a magical place and a tribute to Thailand’s natural biodiversity. Arriving about 12pm, I immediately set-up my cameras and then waited. Feeling dozy, I strung my hammock for a bit of a snooze after the long haul from Bangkok. The afternoon passed-by slowly and about five got up and began a vigil of the mineral lick. A few minutes later decided to actually sit behind my 400mm lens and camera, and do some adjustments to compensate for the fading light. Took a few test shots to make sure the exposure was correct and then waited. Two minutes later, the dream of a lifetime unfolded before me.

Same tiger a month later during the day at the above location

A striped carnivore magically and silently appeared from the forest on my right. The tiger walked straight down to a little stream for a quick drink. The mature male did not linger and continued on his way. However, he did pause briefly to stare up at my position three different times before disappearing into the forest on my left. Total time spent by the cat at the waterhole was less than a minute. I was extremely fortunate to snap 20 frames as the magnificent creature carried on its way. I banged my head against my camera in disbelief to make sure I was not dreaming. After 15 years of wildlife photography, my aspiration to photograph a tiger through the lens has finally come true.

A female tiger in early morning at the same location

The present status of the tiger in Thailand is balancing on the beam of nature. As a World Heritage Site, Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai Naresuan wildlife sanctuaries is the core area and absolutely the last great tiger haven in the Kingdom, and Southeast Asia for that matter due to its size (6,427 square kilometers), and its biodiversity. In Huai Kha Khaeng, the Department of National Parks has really improved the situation with better patrolling, increased help for the rangers, a demarcation fence along the eastern buffer zone in Uthai Thani, constant vigilance by many people and NGOs’ plus improved management, wildlife research and better awareness education. With these measures in place, prey species have come back and are now abundant. Tigers are thriving. There are about a hundred in the Huai Kha Khaeng-Thung Yai block.

Male tiger posing for my camera

Research on the tiger has been carried out by the Wildlife Research Division under the direction of Dr Saksit Simcharoen and his staff in conjunction with several other people and organizations including Dr Ullas Karanth (from India) and Dr Dave Smith from the University of Minnesota.

A waterhole with mineral deposits in Huai Kha Khaeng

Dr Saksit and others has published a paper in the science journal Oryx (How many tigers Panthera tigris in Huai Kha Khaeng: An estimate using photographic capture-recapture samplings) to establish a number. According to Dr Saksit, the home range of the Indochinese subspecies is about 240 square kilometers. Dr Peter Cutter with WWF-Thailand, and also a student with the University of Minnesota, has done his doctorate thesis on ‘tiger’s occupancy monitoring’ using transect and trail sign data gathered in Huai Kha Khaeng.

Tiger entering waterhole

Camera trapping is still by far the best and safest way to establish a home range of a tiger due to its individuality. No two tiger’s striped pattern is alike. It is imperative to use opposing camera traps to get a picture of both sides to identify individuals. Footprint and scat analysis are also very good techniques.

Tiger drinking from shallow stream

In my opinion, collaring a tiger is extremely dangerous as the capture process could possibly injure or impair the animal. As rare as they are, it does not justify losing even one of these magnificent creatures to a possible botched captures and release. Some researchers may not agree but eight tigers in Huai Kha Khaeng have already been collared and ranges determined. You can only get so much data. Loads of tiger home range information has also come from India and elsewhere. I’m all for good passive scientific research (wild animals are not handled at all) carried out to save the tiger.

Tiger looking back at my position

The Western Forest Complex includes 17 protected areas encompassing more than 18,000 square kilometers and has the potential to accommodate 700 tigers. Even though this estimate is high, with good protection and patrolling in all the protected areas in the complex to keep poachers out and encroachment to zero, and to protect the prey species or food chain for the tiger, it is feasible in the future this number could be a reality. However, due to serious fragmentation with roads, dams and reservoirs plus humanity and agriculture, it will be a difficult road ahead unless the present boundaries of the large protected areas stay intact and unharmed, and more corridors set-up through national forests. The World Heritage Site of Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai must be the number one priority of the DNP as a conservation area.

Tiger on the move

For the long run, forest protection and wildlife awareness education to all levels of society is the key to saving the Kingdom’s natural heritage. The government should always strive to use all its resources to keep the forest and wildlife free from the damaging effects of human intervention. The private sector and the government need to be aware of all the problems regarding the forest rangers and try to improve their lives. The forest can be a deadly place to work and these men need incentive, as they put their lives on the line.

Tiger’s final look before disappearing into the forest

Projects to provide food and clothing to help these men are being carried out in a few protected areas by a few individuals, companies and organizations. Without dedicated ranger patrolling, tigers will surely slip away. It is up to the present generation to take proactive measures to make sure Thailand’s wild flora and fauna stays intact for future generations to see, enjoy and cherish.

Ecology and behavior of the Tiger:

To understand how the tiger evolved, we must go back to the beginning of these wild creatures. Nimravidae were the first cats to evolve in the Early Oligocene epoch, about 35 million years ago. They lasted till the Late Miocene, some eight million years ago, when huge grasslands had developed around the world. The large saber-toothed cats were the first of the family Felidae. These long-fanged felines evolved alongside huge herds of grazing mammals like antelope and cattle. There were several different species of saber-tooth, but they all became extinct about two or three million years ago.

Modern cats belong to the family Felidae which includes: tiger, lion, leopard, cheetah, and domestic cats. Ultimate carnivores, they feed almost exclusively on vertebrate prey and sit at the top of the food chain. Wild cats have few predators apart from man. The tiger belongs to the genus Panthera or roaring cats that also includes the lion, leopard and jaguar.

Tiger camera trapped abstract

The Indochinese tiger Panthera tigris corbetti was named after Jim Corbett, the famous conservationist and hunter of man-eating tigers and leopards in India during the 1930s’. This subspecies is found in Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, eastern Burma and southeastern China. According to Chatchawan Pisdamkham, Director of the Wildlife Conservation Division of the DNP, there are approximately 250-300 tigers left in the wild of Thailand.

The following protected areas still harbor these magnificent felids: Huai Kha Khaeng, Thung Yai Naresuan, Umphang and Salak Phra wildlife sanctuaries plus Mae Wong, Sai Yok, Sir Nakarin, Erawan, Kaeng Krachan and Kui Buri national parks in the west; Khao Yai, Thap Lan and Pang Sida national parks, and Phu Khieo wildlife sanctuary in the Northeast, and Hala Bala Wildlife Sanctuary in the deep south.

Tiger camera trap abstract

It is doubtful if any tigers survive in the protected areas of the north or Khlong Saeng-Khao Sok forest complex in the south as no reports have come from these areas for many years. Eastern Thailand has no tigers on record. A couple of years back, the newspapers reported on tiger tracks found not far from the road around several national parks in Chiang Mai and Lampang but were fake put down by a prankster to stir-up media frenzy. This was supposedly to help villagers who had lost cattle to a predator, more likely feral dogs.

Tigers are essentially solitary but come together when a female is in estrus. The resident male will copulate with a female many times over several days. Gestation ranges from 93-114 days. Litters can be from one to seven but usually only two to three cubs survive. Tigresses rarely accompany more than three cubs in the wild and abundant prey is required for a growing family with a small home range about 60 square kilometers.

Indochinese tiger tracks in Kaeng Krachan

It has highly developed vision about six-times more powerful than man and an extreme sense of hearing. These attributes are essential in locating prey. The feed almost exclusively on herbivores and are at the top of the food chain.

Indochinese tiger habitat in Kaeng Krachan

The tiger’s ultimate advantage in stalking prey is its striped pattern that is natural camouflage and this cat is a very efficient killer. It has awesome strength and unmatched armament of retractable claws, long fangs and dagger-like canines. It can sometime dispatch animals as large as gaur, wild water buffalo and small elephants. Tigers have no predators other than humans.