Khlong Saeng: The Lost River

One of the Kingdom’s top wildlife sanctuaries still harboring many endangered but classic Asian animals

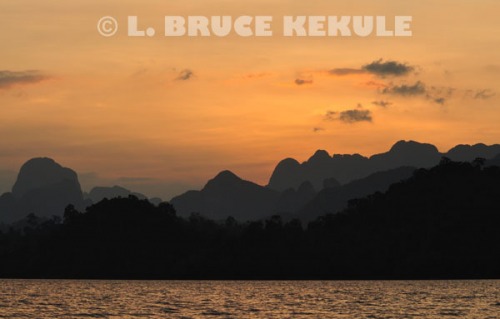

The weather is mostly clear as the sun drops behind a huge cloud close to the horizon. Light monsoon rains have begun at the end of April but hang in the mountains to the west. It has been a scorcher and heat from the day lingers over the reservoir. The light is soft and warm. About 6pm, a small herd of gaur drift out of the forest to drink at the waters’ edge and forage tender new grass. In a boat-blind about a kilometer away, I silently motor the craft closer using a battery operated trolling motor. The timing is perfect as I move in for a shot of Thailand’s magnificent but endangered wild ox.

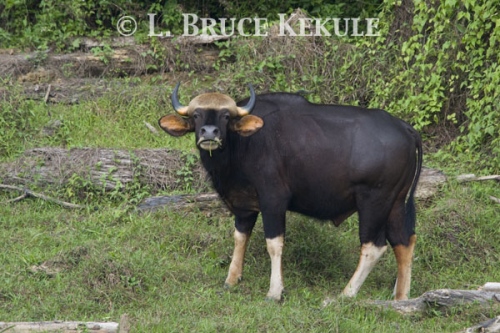

Gaur cow in late afternoon light in Khlong Saeng

As I get closer, a mature cow feeding on an island in the lake sees something moving 100 meters offshore, and swims across to the mainland to investigate, all the time keeping her eyes locked on the strange anomaly moving in the water. Water drips from her underbelly, and her reddish-brown coat and deeply curved horns standout in the late-afternoon magic. I fire off a salvo of images hoping my camera and lens will capture this beautiful creature so late in the day. For a few brief moments, the old cow showcases Thailand’s natural heritage.

Young gaur bull

There are many beautiful forests in the South, but one in particular is truly a tribute to nature. Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary was once a magnificent natural watershed that provided water throughout the year to the inhabitants of the lowlands on the east side of the Thai Peninsula. It still harbors some very impressive animals such as elephant, gaur, tapir, serow, sambar, clouded leopard, sun bear, Great Argus (second largest of the pheasant family in Thailand), and the mighty king cobra – and the list goes on.

Gaur calf

Royal Decree encompassing 1,155 square kilometers of dense forest established Khlong Saeng in 1974. The sanctuary is the biggest in the Khlong Saeng – Khao Sok Forest Complex totaling more than 5,316 square kilometers and incorporating 12 protected areas, 11 of which are terrestrial and one with offshore islands in the Andaman Sea. Its forests are predominantly moist evergreen and most of the plants and animals are of Sundaic origin with some Indochinese species interspersed.

Curious gaur cow

Situated in the provinces of Surat Thani, Phang Nga, Ranong and Chumphon, the complex includes: Khlong Saeng, Khlong Yan, Khlong Naka, Khuan Mai Yai and Ton Pariwat wildlife sanctuaries, and Khao Sok, Kaeng Krung, Lam Son, Sri Phang Nga, Khao Lampi – Hat Thai Muang, Khao Lak – Lam Ru and Khlong Phanom national parks. They are under the responsibility of the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department (DNP) to provide protection, management and staff.

Gaur in the late afternoon

Khlong is the southern Thai word for a tributary or canal. The main tributaries of the Khlong Saeng valley include the Saeng, Ya, Yan, Ake, Mon, Ye and Mui that made-up the mighty Khlong Pasaeng. This river ran wild from the Phuket Range down to the Mae Tapi River in Surat Thani and eventually into the Gulf of Thailand. The riverine habitat teamed with flora and fauna, and the ecosystem was absolutely pristine. Tigers and leopards lived alongside many prey species like sambar, muntjac and wild pig. Elephants and gaur were fairly common. It was a magnificent wilderness at one time.

Gaur cow and her calves

But in the mid-1980s, a drastic change to the Pasaeng River was to come about. To increase Thailand’s electrical power needs, and back when building hydroelectric dams was in vogue, it was decided by the Electrical Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT), a state enterprise, and the government, to construct the Rajaprabha Dam that eventually inundated a total of 165 square kilometers (65 sq. miles) of the Khlong Saeng valley to become the Chiew Larn reservoir in 1986. The water body extends into the sanctuary for more than 50 kilometers (30 miles) but is only about two kilometers at its widest point.

Flooded forest in Khlong Saeng

Where rivers and forest previously existed, large waterways now provided easy boat access to virgin wilderness. The skeletal forms of what were once huge forest trees stand as a reminder of what disappeared beneath the flood more than a quarter of a century ago. Some trees still stand but many have come crashing down especially up-stream where decaying is severe. Millions of plants and animals perished as the floodwaters rose. The late Seub Nakhasathien, one of Thailand’s hero’s of wildlife conservation plus rangers and wildlife researchers saved hundreds of stranded fauna caught on islands. There are some 160 of them scattered throughout the reservoir when water levels are low. Some denizens were able to swim and move to higher ground but not all. It was the beginning of a new ecosystem – a large lake with a very long and complicated shoreline.

White-bellied sea eagle with a fish

Probably the most impressive scenic site in the sanctuary is the massive limestone ‘karst’ formations that were formed sometime during the mid to late Permian over 200 million years ago. It was a time of widespread mountain-building and volcanic activity. Thailand was part of Gondwanaland that was still attached to Pangaea, the ‘Supercontinent’. These colossal outcrops, some reaching as high as 960 meters (3,150 feet), look almost ‘architectural’ in design and are as impressive as the famous towers in Phang Nga Bay to the south. These configurations are the remnants of a prehistoric coral reef that once thrived here.

King cobra hunting for prey

Of all the animals in Khlong Saeng, gaur is probably the icon of wildlife in the sanctuary. These bovid are now rare in Thailand surviving only in a handful of protected areas, but they thrive fairly well. However, this only occurs around the upper reaches of Khlong Saeng and several other tributaries. The population of gaur here is estimated to be about 100 individuals and is one of the Kingdom’s best reserves for the species due to the dense moist evergreen forest.

Osprey in the mid-day heat

Breeding seems to be healthy; as many calves and young gaur of various ages have been seen in several herds I photographed at this site. Large solitary bulls keep the herd in stable breeding condition. These herbivores need huge tracts of forest free of human presence to survive. Being extremely shy, these wild cattle flee on the first sign of man. Good availability of food, water and minerals are important to their survival and the sanctuary provides these in abundance. There are still some elephants but their numbers seem to have declined. Further downstream, human activity has all but obliterated the large mammals including the tiger, which has not been seen for more than twenty years, even after extensive camera-trap surveys carried out by the research unit at the sanctuary headquarters.

Young Asian Tapir camera-trapped

Next door to Khlong Saeng is Khao Sok National Park covering 739 Square kilometers established in 1980. Khao Sok is well known around the world. The national park’s mandate in Thailand is to promote and encourage tourism into various nature sites within the protected area. After the Rajaprabha dam was completed, boats and wooden rafts were built at an alarming rate to accommodate this new business of boating visitors into the lake. Now there are hundreds of craft, many extremely noisy. Fishing was allowed and it was a free-for-all in the beginning with everyman for himself. All forms of fishing were used including explosives, electricity, nets, trap-lines and spear guns. Many areas were quickly depleted of fish, and fisherman must now venture deeper into the reservoir trying to eek out a living.

Old bull gaur camera-trapped

Actually, the Fisheries Department (FD) has a regulation in place that states ‘no fishing’ is allowed from the dam five kilometers to the limestone cliffs during the breeding season from 15th May to 15th September. This ban should extend completely into Khlong Saeng. Unfortunately, there seems to be little or any formal protection in place as boats and people come and go with no restrictions. Also, in Khao Sok, there are many rafts that have extensive facilities including a ‘karaoke’, which seems distant from nature. Every year the FD releases several species of fish into the reservoir. The ‘giant catfish’, a species found in the Mekong River, was released here and are most likely competing with other large resident fish. The FD has banned its capture but all fish are being caught for the pot, or sale to waiting ice vendors at the dock.

Dusky langur on a stump

However, a more serious problem exists that needs immediate attention before it is too late. When the Rajaprabha hydroelectric dam was finished and working on-line, EGAT passed a regulation and transferred protection duties to Khao Sok National Park. This included the complete waterway and 100 meters up into the terrestrial landscape meaning the entire water body intrudes deep into Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary for more than 50 kilometers and the mandate for its use and protection is controlled by the national park. People easily penetrate Khlong Saeng to poach, gather and fish, and the sanctuary officials have no authority on the waterway. Budgets are low and therefore, protection and enforcement is minimal. It is an extremely large loophole that needs to be fixed soon!

Gaur cow feeding on grass

EGAT, DNP and FD should join forces to find a viable solution, and take corrective steps to re-zone the reservoir. The solution is easy. About 20 kilometers into the lake at the mouth of Khlong Mon, the lake narrows down to about two hundred meters across. A rope barrier and guard post has been erected by the sanctuary but is unmanned for the most part due to the national park’s mandate. Constant overfishing and visitation to the upper reaches of Khlong Saeng over the long run will definitely have a serious impact on this sanctuary, especially gaur due to their very shy nature. Another very sensitive species is the Great Argus. These beautiful birds will abandon a breeding site if disturbed by humans. There are six hornbill and two gibbon species indicating a pristine forest. Stump-tailed macaque is the largest primate and dusky langur or leaf-monkeys are common. White-bellied sea eagle, lesser fish-eagle and osprey plus otters depend on fish and even though there is still some species in abundance, saturation fishing will eradicate most fish over time.

Sunset over the Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

The DNP’s mandate for ‘wildlife sanctuaries’ is straightforward; they have been set aside for wild species propagation, biodiversity research and habitat preservation. With hundreds and possibly thousands of people visiting Khlong Saeng every year, it is doubtful whether the sanctuary can sustain its habitat diversity over the long term. Also, trash and oil pollution from the boats is serious problem that needs attention and constant surveillance.

Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary is a beautiful but forbidding forest, and its incredible biodiversity it a tribute to the Kingdom’s natural heritage. In terms of research, very little is actually known about the interior but its future depends on many things. Most of all; the protected area should become the focus of attention so that all concerned may take a hard long look and save it for the future. Decisive and quick action in the only recourse before it is too late.

In the field:

After more than a decade of visiting forests in the East, West and North, I decided it was about time I went down South. From January 2009, I began a photographic and camera-trap program in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary. Over the course of five months, a trip every month was scheduled. On the very first outing, we arrived at our final destination after a four-hour boat ride. I jumped onto a floating raft (ranger station) not far from the headwaters of the Khlong Saeng. After a few minutes of unpacking and getting settled in, someone shouted out that an elephant was by the waters’ edge across from the ranger station in plain sight.

Young tusker elephant in Khlong Saeng

What a strange bit of luck. We immediately jumped back in the boat and crossed over to where a young tusker was feeding on bamboo leaves and occasionally taking a drink from the lake. He was alone and we could not figure out why. Possibly the herd bull or an old belligerent cow elephant had pushed him out. We will never know. This little bull was in good condition and looked fine. The next day, I was back at the same spot waiting but he did not show. The morning after, he was back. I left the next day but before we parted company, I decided to name him ‘Nong Saeng’ after the river. I thought that would be the last time I would see the little youngster.

Young bull gaur

A month later I was back at the station and the first thing I asked; where was ‘Nong Saeng? No one had seen him. Two days later about 4pm while I was traveling up-river in my boat-blind, I bumped into him again, but much farther into the reservoir. He was back by the shoreline feeding and I was elated to say the least. I stopped the boat and had a great time photographing this lively young elephant once again. He was seen a couple more times by the rangers but since then, ‘Nong Saeng’ has probably gone up into the hinterland as the monsoon rains have begun. This encounter will always create fond memories of nature’s little quirks and how things work out sometimes. Hopefully, I will get a chance to see him again next year in January when I return to continue documenting the wildlife at Khlong Saeng.