Posts Tagged ‘avian fauna’

Vultures in India…important birds for the habitat…!

While I was on safari in April 2016, I was lucky to get some nice vulture shots on a carcass at Corbett Tiger Reserve and then at a cliff-face in Panna Tiger Reserve.

Himalayan Griffon , Red headed and Cinereous vultures plus a crow on a carcass in the Dikhala grassland in Corbett Tiger Reserve…!

A Himalayan Griffon vulture flying into a spotted deer carcass…!

Long-billed vultures an a cliff-face in Panna Tiger Reserve…!

A vulture on the wing in mid-morning in Panna Tiger Reserve…!

Cambodia is for the Birds: photographing the Giant Ibis

The Northern Plains of Cambodia: Only 250 giant ibis left in the world…!

A giant ibis lifting off from a trapeang (waterhole) in late afternoon.

In early Feb. 2011, the flight to the city of Siem Reap near Angkor Wat in northern Cambodia took about 45 minutes by jet from Bangkok. We touched down safely and the trip was smooth arriving about noon. Going through immigration and customs was fairly quick and hassle free. I then waited out front at the coffee shop and had some lunch and a drink while I waited for my fellow wildlife photographer Allan Michaud, to show up. He lives and works in Phnom Penh and has been there for many years.

A mature giant ibis close to our photographic blind.

After an hour wait, he showed up with a car and taxi driver, and we loaded-up for the trip further north to a place arriving in the late afternoon some 60 kilometers south of the infamous temple ‘Preah Vihear’ (also known as Phra Wihan in Thai) on the Thai/Cambodian border. The centuries old structure sitting on a ridgeline has been the center of controversy, and fighting has erupted many times between the two countries both claiming ownership. The International Court of Justice in The Hague ruled in 1962 and again recently that the temple belongs to Cambodia.

A giant ibis showing wing flair on the first morning.

The taxi got us to our drop-off point safe and sound. The ride up from Siem Reap was hair-raising to say the least as the driver was continually passing slower traffic at break-neck speed around blind corners, and it was white-knuckle for me, and Allan. However, he was more use to living and riding around Cambodia and I had already experienced one bird photography tour a couple years earlier down to the flooded forest on the northern tip of Talay Sap, Southeast Asia’s largest freshwater lake close to Siem Reap. The taxi ride to the lake then was no different.

The same bird taking off.

We finally arrived in the middle of nowhere and several motorcycle taxis were waiting on us. Allan and I loaded up for the two-wheeled part of this trip. By the time we got to the ecotourism lodge set-up in Tmatboey Ibis Ecotourism Project in Kulen Promtep Wildlife Sanctuary in the Northern Plains, it was already late afternoon. We quickly had dinner and retired to our rooms being exhausted from the grueling trip to the lodge setup in the forest. The next morning, we had a quick breakfast and then at 5am, jumped on the motorcycles once again: this time with cameras and daypacks for a trip to a known ibis waterhole, also known as a ‘trapeang’ in Cambodian.

An ibis with food in its beak.

When we got to our destination, the forest was quiet. I looked around and found a tree in a depression that looked perfect for a photographic blind. We quickly set the enclosure with camouflage cloth but decided to leave it till the next morning. We then went looking for other possible ‘ibis’ haunts but these proved to be empty. The next morning, we were back in the blind before dawn and sat quietly waiting. About 7.30am, a lone mature giant ibis landed on a tree high up and called out. We both started shooting and it was great to see this amazing feathered creature on the first day.

A flock of giant ibis feeding at the trapeang.

About 8am, the thundering sound of artillery fire began north of our location. At first, it sounded like carpet-bombing that I had experienced in the Vietnam War back in 1968 while I was working there. And then it dawned on me and Alan: the Thais and Cambodians were shooting at each fighting other over the temple at ‘Preah Vihear’ again. We ignored it and decided to stay put. The next morning, it was a repeat with the thunderous noise for about an hour but it finally stopped.

We sat all day and about 4.30pm, heard and then saw a flock of five giant ibis as they swooped down and landed in front of us on the ground. These huge birds stayed for about 15 minutes foraging and feeding and after they left, my good pal and I let out a whoop. We had just photographed one of the rarest birds on earth and it was a celebration that night with drinks and food at the lodge. Looking back, the ‘Spirits of the Forest’ had answered my prayers and the feeling of accomplishment was overwhelming.

Another giant ibis photographed by my friend Allan Michaud.

My last shot of a giant ibis taking off from the trabeang in late afternoon.

The giant ibis Thaumatibis gigantean has a distinct curved bill, and at dusk and dawn have a repeated, loud, ringing call sounding like ‘a-leurk a-leurk’. The adult is dark grey and the head and upper neck are bare-skinned. There are dark bands across the back of the head and shoulder area and the pale silvery-grey wing tips also have black crossbars. The beak is yellowish-brown, the legs orange, and the eyes dark red. Juveniles have short black feathers on the back of the head down to the neck. Their bills are shorter and their eyes are brown. They consume mainly invertebrates, particularly locusts and cicadas, as well as crustaceans, small amphibians, small reptiles, and seeds.

Hornbills: Indicator species of an intact ecosystem

WILD SPECIES REPORT

Majestic birds and living fossils

Wreathed hornbill in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Most people are familiar with the hornbill, nature’s amazing avian fauna with large bills and a casque, and some with raucous calls. They also have strange but interesting nesting habits and the larger hornbills make a loud whooshing noise when flying sounding much like a locomotive, and heard from quite a distance. In any given forest, if they thrive it means the ecosystem is fairly intact.

Brown hornbill at a ground nest hole in Huai Kha Khaeng

The hornbill belongs to an ancient family (Bucerotidae) of birds seen in fossils from the strata of the ‘Eocene’ period of Europe some 50 million years ago. Through tectonic-plate movement, hornbills however have become restricted to tropical Africa and Asia, and there are 55 species found in the world with 24 in Africa and the rest surviving in the forests of South and Southeast Asia. Thailand has twelve species recorded throughout the country, and all still thrive but some are endangered.

Wreathed hornbill with fruit for his mate in the nest

These noisy, social, omnivorous birds need large tropical forest areas with many fruiting trees throughout the year to survive. Giant emergent trees with nesting cavities are also important to carry on their legacy but some species nest near the ground. The diet of the hornbill is a preponderance of figs and other fruits but also take animal food such as snakes, lizards and small bird hatchling needed for dietary protein when rearing the chicks.

About six years ago, my dream to photograph hornbills at a nest became a reality. The month is May and I’m sitting in a hot, humid blind in the dry evergreen forest of Kaeng Krachan National Park. The location is near the 9th tier of Thor Thip waterfall about 10 kilometers from Phanern Thung ranger station in the interior of the protected area.

Great hornbills flying off a fig tree

A pair of wreathed hornbills was sighted coming and going from a nest-hole by a forest tour guide, and relayed to my close friend Suthad Sappu who has been a ranger with the park for more than 15 years, who informed me and I made immediate plans to make a visit. It took me a few days to get going and I finally loaded up my old 4X4 pickup truck making my way out of Bangkok to Phetchaburi province in southwest Thailand, a three-hour ride.

We eventually arrived at the end of the road at Kilometer 36 and immediately got ready for the 4-plus kilometer walk downhill to the waterfall along a well-established nature trail. On a hill across from a tall tree with a large hole in it, I quickly set-up a blind and went into hiding.

Rufous-necked hornbill in Mae Wong National Park

A pair of wreathed hornbills chose this cavity for their nest. By the time I got there, the female was already inside and the front had been closed-in with droppings. This chore is taken care of by the female so that just a small slit is left. The perch above the hole is just right to allow the male to feed the occupants with fruit and small animal morsels.

In a short while, a loud whooshing noise was heard and the male hornbill arrived as the morning light glowed. The large bird popped out fruit and gingerly fed the female. It was a beautiful experience seeing and photographing this great natural spectacle. After filling my card with digital images, I waited until the bird left on another fruit gathering mission and then left quietly. As always, this sighting is etched in the old memory bank.

Wrinkled hornbill in Hala-Bala Wildlife Sanctuary

The chicks eventually hatched and the cycle of life began for yet another group of hornbills. The female finally emerged and left the young ones in the nest for a while longer as the adults continued to feed them. One day, they eventually outgrew the nest and broke free. It is one of the greatest success stories of the natural world.

Hornbills unfortunately have been persecuted for their large bill and casque as an ornament. Poachers for subsidence also eat these large birds. This has greatly impacted all species of hornbill throughout the Kingdom but there are still many protected areas where they can be found. Many are near extinction at the hands of man in his quest to survive with the destructive forces of encroachment and poaching.

White-crowned hornbill in Hala-Bala

In 1996, Japanese photographer Atsuso Tsuji published an excellent book in conjunction with Sarakadee Press entitled ‘Hornbills – Masters of Tropical Forests’ about these amazing creatures. This tome is now out of print but probably can be found in some used bookstores. With many photographs and text, he delves into the lives of hornbills in Khao Yai National Park. There are chapters on nesting, roosting and feeding habits, and in particular the entire life cycle of hornbills.

A story about hornbills in Thailand would not be complete without mentioning biologist Dr Pilai Poonswad with Mahidol University who has dedicated her life to the study and research of this magnificent avian fauna, and she has also published a scientific journal concerning the subject. Her work has included helping hornbills to choose nest holes by installing a ledge just below the cavity to allow these large birds to perch easily while feeding the female and chicks inside.

Great hornbill in Khao Yai National Park

I was very fortunate to photograph a great hornbill male in Khao Yai while it visited a nest very close to the main road in the park shown in the story. Ajarn Pilai and her team has also worked in other protected areas like Huai Kha Khaeng, Hala Bala and Khlong Saeng wildlife sanctuaries, and Keang Krachan and Khao Sok national parks plus many others throughout Thailand to monitor these birds, and she has established the Hornbill Research Foundation to further the study and protection of these majestic animals.

Down south in Surat Thani in the rich forests of Khlong Saeng next to Khao Sok, I did a camera trap survey deep in the interior catching many animals including a white-crowned hornbill down on the ground next to a large waterhole shown in the story. I also photographed a brown hornbill at a nest hole on the ground in Huai Kha Khaeng.

Oriental pied hornbills in Kaeng Krachan

My close friend Sarawut Sawkhamkhet photographed a pair of Oriental pied hornbills at a waterhole in Kaeng Krachan. Another fellow wildlife photographer Saman Khunkwamdee photographed helmeted and rhinoceros hornbills many years ago down in Hala-Bala Wildlife Sanctuary during peacetime in Southern Thailand on the border with Malaysia. Another close friend Vanchai …….a has photographed all 12 species, quite a feat and just recently visited Hala-Bala capturing the very rare wrinkled hornbill and others in the sensitive south.

The future of the hornbill in Thailand is the same for all species that inhibit pristine forests; they must be protected at all costs from destruction by encroachment and poaching. This responsibility rests with the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation, and it is imperative that the management, protection and enforcement is greatly improved so that the magnificent protected areas remain intact. The government and private sector should work together to insure hornbills and all the other creatures and ecosystems remain part of Thailand’s amazing natural heritage.

Oriental pied hornbill with fruit for its mate

According to the very informative ‘Birds of Thailand’ by Boonsong and Round, there are 12 species of hornbill found in Thailand as follows:

1) White-crowned hornbill (Berenicornis comatus) with a bushy white crest and blackish bill and a small casque. Habitat is evergreen forests from foothills to 1000 meters, and is an uncommon resident.

2) Brown hornbill (Plilolaemus tickelli) is relatively small in size and brown plumage with white orbital skin and yellowish bill and small casque. Found occasionally in mixed deciduous forest adjacent to evergreen forest up to 1,500 meters. They are an uncommon resident.

3) Bushy-crested hornbill (Anorrhinus galeritus) has mainly black plumage with a small casque and a thick, drooping crest and pale blueish gular and orbital skin. Found in evergreen forest from the plains to 1,000 meter. They are fairly common resident.

4) Rufous-necked hornbill (Aceros nipalensis) is identified by a combination of bright blue orbital skin and bright orange-red gular pouch, and yellowish ivory bill with no casque. Found in evergreen and hill evergreen from 600 meters to 1,800 meters, and is a rare resident.

5) Wrinkled hornbill (Rhyticeros corrugatus) has all black wings and is distinguished from wreathed hornbill by smaller size. Yellowish bill and small reddish casque. White gular pouch in males and blue gular pouch in males. Found in lowland evergreen forest in the South. Rare with just a few left in Southern Thailand due to habitat destruction.

6) Wreathed hornbill (Rhyticeros undulates) shows all black wings with a white tail, and black bar on gular pouch that is yellow in males and blue in females. Diagnostic corrugations on sides of both upper and lower mandibles. Found in evergreen and mixed deciduous forests from the plains to 1,800 meters. They are an uncommon to locally common resident.

7) Plain-pouched hornbill (Rhyticeros subruficollis) in coloring is similar to the wreathed hornbill but distinguished by slightly smaller size. Lacks corrugations on sides of bill. Found in evergreen and mixed deciduous forests of the lowland and lower hills. They are a rare resident.

8) Black hornbill (Anthracoceros malayanus) is small in size with all black plumage with white tips on tail feathers. The bill is yellowish white in the male and blackish on the female and both with a whitish cassque in both sexes. They are found in evergreen forests in the plains and foothills, and are a rare resident.

9) Oriental pied hornbill (Anthracoceros albirostris) is identified by its small size, whitish face patches, white lower breast and belly. The bill and casque is ivory-colored and marked with black with casque larger in males but more heavily marked blackish in females. Can be found in evergreen and mixed deciduous forests and secondary growth from the plains up to 1,400 meters, and is a fairly common resident.

10) Rhinoceros hornbill (Becerous rhinoceros) is very large and mainly black with a white belly and tail marked with broad black band. Large upturned casque is reddish and bill yellow, and is lighter in color on the female. They are found in the extreme south of Thailand in evergreen forests from lowlands up to 1,200 meters, and are a rare resident.

11) Great hornbill (Becerous bicornis) is very large and is easily recognized by golden-stained white wing bar and white trailing edge to wing and by white tail with black band. Red eye in males and white eye in females. Mainly with a yellow bill and casque. They are found in evergreen and mixed deciduous forest from plains up to 1,500 meters and found on some offshore islands. Uncommon to locally common residents.

12) Helmeted hornbill (Rhinoplax vigil) is large with a elongated central tail feathers. Blackish brown with a white belly. Short conical bill and rounded casque is red. They are found in evergreen forests from plains up to 1,200 meters and is, an uncommon to rare resident.

Gurney’s Pitta – The last few stragglers

WILD SPECIES REPORT

Avian fauna on the brink of extinction in Thailand

Gurney’s pitta male – one of the last few surviving birds at Khao Nor Chuchi

In October 2001, I did a story entitled ‘On the verge of extinction’ for the Bangkok Post Nature section about an amazing bird that had been rediscovered in 1986 by my close friend and associate Phillip D. Round, Thailand’s eminent ornithologist after almost three decades of no sightings. Prior to that, it was thought to be extinct in the Kingdom. The bird was listed as a flagship species for conservation and put on Thailand’s 15 reserved species list.

The Gurney’s pitta Pitta gurneyi is a medium-sized passerine bird that completely disappeared from all lowland evergreen forest south of Prachuap Khirikhan province where natural forest was destroyed primarily to grow palm and rubber trees except for one little patch in Krabi province. This site is known as Khao Nor Chuchi or Khao Pra-Bang Khram Wildlife Sanctuary – the only known place in Thailand where this rare pitta still survived. The area definitely needed extreme management to save this creature from extinction.

A Gurney’s pitta female in Khao Nor Chuchi

In historic times, the range of the Gurney’s pitta was along the coast and inland areas on both sides of the Thai peninsula, in the provinces of Trang and Krabi on the western side, and Nakhon Si Thammarat, Surat Thani, Chumphon up to Prachuap Khirikhan on the east.

It also survived in southern Burma where this beautiful bird was first discovered way back in 1875 by a wildlife specimen collector working for Allan Octavian Hume, a prominent ornithologist. The exotic bird was named rather prosaically after Hume’s friend, J.H. Gurney, a Fellow of the Zoological Society of London.

Lowland rainforests up to 200 meters above sea level are home to an unsurpassed diversity of flora and fauna including the Gurney’s. Due to excessive human settlement and agriculture, this unique bird has diminished to the point of no return here in Thailand.

A male Gurney’s pitta photographed is 2001

Encroachment and forest destruction has not been the lone evil. Some poaching of the Gurney’s for the black market trade have also taken its toll. It is said a pair of a male and female fetches a hundred thousand baht or more from rich collectors of exotic birds at the infamous Chatuchak Market in Bangkok. In fact, the bird’s beauty has been its worst enemy. Even though protection and enforcement has improved over the years, catching the big traders and buyers of wildlife black market items has been slow and sometimes non-existent at times.

However, over in Burma, thousands of Gurney’s are purported to survive after quite a few surveys since early 2003 when Jonathan Eames with BirdLife International and other associates found the bird at four different sites. Jonathan returned in 2004 and found more locations with the bird but political instability and very restrictive government regulations threaten to keep researchers away, while landmines and bandits further discourage access.

Since then, Dr Paul Donald of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) has surveyed many areas and confirmed that almost all of the world’s population of Gurney’s pitta is located in Myanmar but the forests there are also being decimated for palm and rubber agriculture and hence, the bird there is still under serious threat. This granted the species a reassessment from the IUCN, going from critically endangered to endangered.

Hooded pitta with worms feeding its chicks somewhere in the forest

My first encounter with a Gurney’s was back in 2001 when I made an effort to capture this bird on film. The following is an account of that wonderful moment that was very brief, and I only managed to get one shot shown in the story.

“Dark morning stillness in thick lowland rainforest is broken by muffled footsteps as two humans move slowly down the trail. We carry heavy camera equipment to a photographic blind erected deep in the jungle the previous evening. Condensation is heavy as I set up in the hide. My friend and guide, Douglas Judell departs quickly and noisily – the intent being to convey the message that both of us have left the area.

As animals of the night retreat, I wait for the first signs of dawn. My goal is to photograph this elusive pitta known to frequent this small patch of forest. Morning light awakens the jungle and the sounds of dripping moisture begin to be replaced by the noise of birds and insects starting their day. Hidden in the blind, I remain vigilant for the slightest movement on the forest floor. About 8am, light from the sun filters through the canopy in patches.

One of several hooded pittas that showed-up looking for earthworms

A sudden movement shows a hooded pitta, another species common here, hopping about looking for earthworms. This striking blue, green and red bird with a dark brown crown moves closer to the blind seemingly oblivious to the looming structure. Snapping only a few shots for fear of alarming the other denizens of this forest, I continue to sit quietly hoping the ‘forest spirits’ will answer my wish.

A passing morning rain shower quickly passes by and as if on cue, a blue, black and yellow bird suddenly appears in front of the blind about five meters away. Perhaps sensing danger, it quickly hops into the darkness of the forest but a minute later returns just long enough for only one shot of this rare bird. I quickly forgot about the wet grubby conditions and the long road trip of more than 700 kilometers from Bangkok to this place. I was elated to say the least.”

My first Gurney’s pitta male photographed by ‘U’ trail

When I did the story in 2001, there were about 11 pairs and some individuals left in the sanctuary. The decline was evident and it became a worry for the Department of National Parks (DNP). Drastic measures were needed but they never came. When Khao Pra-Bang Khram was up-graded in 1987 by the Royal Forest Department (RFD) from a non-hunting area to a wildlife sanctuary, most of the forest where the bird was actually found unfortunately was not included in the protected area. It is a wonder how things sometimes come to pass.

This then became a pitched battle between conservationists, local villagers and the DNP. Forests were being cleared for palm and rubber and there was nothing the department or NGOs’ could do in certain areas because this land was outside the sanctuary and was the property of the locals. Forest destruction was severe and it put a terrible strain on the ecosystem.

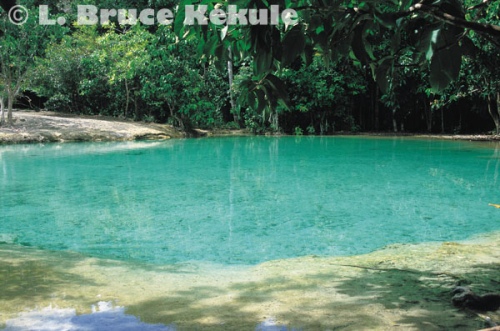

Emerald pond algae not far from the sanctuary headquarters

Another very negative aspect is the visitation by hundreds of tourists almost daily at the Emerald Pond not far from the core area. This place use to be peaceful and beautiful, and a decade ago there were just a few noodle stands and trinket shops at the front. Now this has expanded 100 percent and has become a big business catering to the visitors. Buses and vans are parked everywhere. There are very few birds around the pond now and trash is a serious problem.

Two weeks ago, I made one last ditch effort to photograph this bird. Permission to enter the sanctuary was graciously given by the Wildlife Conservation Division at DNP in Bangkok. I packed-up my old pickup truck and headed South to the small village in Krabi province named Ban Bang Tieo where the sanctuary headquarters is situated.

I met with the new superintendent Nikom Srilamoon of Khao Pra-Bang Khram, requesting authorization to enter the sensitive area in order to catch the Gurney’s on digital. He has certainly inherited a tough job!

Emerald Pond in Khao Pra-Bang Khram

The first day was comprised of walking the nature trails ‘U’ and ‘N’ where the bird is normally found to see first hand the situation on the ground. Many parts are, overcome by humans and their destructive vises of throwing trash on the ground and cutting trees down. Someone has established a rubber plantation in the remaining core area of the sanctuary. Motorcycle tracks are everywhere and it is said spot-lighting for night creatures like frogs and mouse deer goes on. It seems that just about every square meter is under threat.

The next morning, I decided to set-up a quick blind in a palm plantation that borders forest early the next morning at first light. About 7am, a couple female pitta skirted the forest for a couple of meters and then melted back into the thick vegetation. I did not get a shot, as they were too quick.

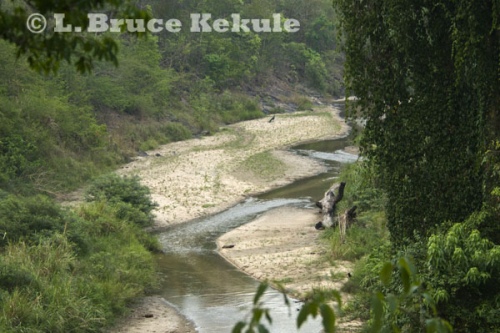

Palm oil plantation butted-up to the forest in Khao Pra-Bang Khram

In the afternoon, I went back into the trail system to scout a new location. I chose to erect a blind in a gulley with a stream that cuts through the habitat. Sharp thorns are everywhere but it is very secluded from the main nature trails and excessive activity.

The following morning I was sitting alone in the dripping forest at 5.30am sharp. My two helpers departed quickly after installing a slave flash on a tree to the left of my position. Then the rain started and did not let up until late afternoon when the sun finally peaked through the clouds for a short period.

Another male photographed in the sanctuary

Birds immediately began calling and activity picked up. Then, I saw movement ahead and a male Gurney’s popped out of the forest and stayed in front of the blind for only a few seconds as I fired off a short burst including the lead photo. It was exciting, and will be etched in memory. These creatures are still surviving here but they are now hard to locate and stay elusive for the most part. I thanked the ‘spirits of the forest’ for this rare encounter, and the rain came again till just before darkness.

BirdLife International, BirdLife Denmark, DANCED, Bird Conservation Society of Thailand, the Oriental Bird Club and the RSPB have helped the DNP to implement numerous projects at Khao Nor Chuchi, but these efforts have only slowed rather than halted new settlements and the destruction of the forest.

Banded pitta male at Khao Nor Chuchi

The population of Gurney’s pitta at Khao Nor Chuchi has declined drastically, dropping from an estimated 40 pairs in 1986 down to about 20 pairs in the mid-1990s’. At one abandoned nest, local researchers found bird (mist) nets placed by some people to capture this rare bird. The last estimate from various sources on the number of birds is less than ten individuals (both male and female) survive in the core area. This is serious and the prospect of extinction is truly depressing.

Banded pitta female at Khao Nor Chuchi

Unless Khao Pra-Bang Khram protection and enforcement can be quickly implemented and expanded to include all the remaining intact lowland forest, and previously cleared areas are reforested, the species in Thailand faces a very bleak future. Quick and decisive action is the only remedy and it is absolutely no use pointing the finger of blame on anyone.

As a flagship species for the conservation of southern Thailand’s lowland rainforest, only time will tell if the Gurney’s pitta can survive. If this beautiful creature disappears, it will be a sad day for nature conservation in the Kingdom.

THAILAND’S 15 RESERVED SPECIES

Thailand’s list of 15 reserved species is so out-dated it is now covered in dust and needs updating. Two lists should be established: one for species that are truly extinct in the wild, and another list for rare creatures like tiger, leopard, gaur, banteng, Asian elephant, Asiatic bear and sun bear plus the remaining survivors shown below. There are also many other wild animals that need special status!

1) White-eyed river martin: Presumed extinct globally since 1985-86. The last known specimens were from Bueng Boraphet Non-hunting Area in Nakhon Sawan province.

2) Javan rhino: Once found in many large forests and now extinct in Thailand for more than 25 years.

3) Sumatran rhino: Extinct in Thailand for more than a decade or two. A few individuals were reported in Hala-Bala Wildlife Sanctuary. down south in Narathiwat province.

4) Kouprey or grey ox: Extinct in northeasternThailand for at least 30-50 years and absolutely no reports from Cambodia although extensive surveys have been carried out. The Khmer Rouge during wartime is probably responsible for their demise.

5) Dugong or sea cow: Extremely endangered in the seas of Thailand. There are a few survivors but are probably doomed by excessive fishing and tourism.

6) Wild water buffalo or Asiatic buffalo: Endangered with about 50 individuals surviving in only one location: Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in western Thailand.

7) Eld’s deer: There are two sub-species (Siamensis and the Burmese) and both are extinct in the wild of Thailand.

8) Schomburgk’s deer: Extinct globally since 1935. They were endemic to the Central Plains of Thailand and the last one was killed in a temple in Samut Prakan by a village drunk in 1932. Sad fact!

9) Serow: These goat antelopes are endangered but they still survive in some mountaInous areas that are protected. Their horns are eagerly sought after and used in making knives for fighting cocks in the South.

10) Chinese goral or grey tailed goral: These goat antelopes are seriously endangered; a couple of hundred might live on mountaintops in northern Thailand.

11) Gurney’s pitta or black-breasted pitta: They are technically extinct in Thailand. There are a few individuals surviving in Khao Phra-Bang Kram Wildlife Sanctuary in Krabi.

12) Eastern Sarus crane: Extinct in Thailand for more than 50 years. They do survive in Vietnam and Cambodia but their numbers are low.

13) Marbled cat: They still survive in the thick evergreen forests of Thailand but their numbers are unknown.

14) Asian or Malayan tapir: They still survive in the western flank of Thailand from Thung Yai Naresuan WS all the way down to Malaysia. However, they are hunted for bush meat in many places in the South.

15) Fea’s muntjac: They still survive in the western flank of Thailand from Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary all the way down to Phang Nga and Surat Thani in the South, and are hunted for meat throughout their range.

PLEASE NOTE:

While I was researching the Gurney’s Pitta on the web, I found a resort website in Krabi using my ‘first’ Gurney’s pitta photograph with out my permission. On photographs of great importance, I will now be using a new watermark covering the subject matter with my name and copyright. I regret this action but do not appreciate people stealing my photographs off the web for their own business purposes. These people have no professional ethics!

CREDIT FOR PHOTOGRAPHS

I would like to thank my good friend Kanit Khanikul for the use of his photographs of Gurney’s and Banded pittas. He certainly has one of the best collections of birds from Khao Nor Chuchi in Thailand and he has spent a lot of time and money recording avian fauna there. He should be praised for his great work!

Red Jungle Fowl – Wild ancestor of the domestic chicken

WILD SPECIES REPORT : Endangered Asian Galleopheasants

Red jungle fowl in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

It is 3am in lowland dry evergreen forest of Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary in eastern Thailand. Close by, a familiar sound is heard waking me up from sleep in my hammock. I’m at the wildlife research station close to the headquarters area of the sanctuary during the breeding season. A male red jungle fowl Gallus gallus has just emitted the well known ‘cock-a-doodle-do’ on the hour as its kind has for thousands of years.

These birds are quite common in Khao Ang Rue Nai that borders Khao Soi Dow Wildlife Sanctuary in the Southeast, and is a haven for this Galleopheasant. It has been determined the species is the ancestor to the domestic chicken.

Red jungle fowl male taking off from tree branch

After a quick cup of coffee, I ready my photographic equipment and head out into the bush about 6am at first light with my main lens and camera mounted in the window of my Ford pick-up. I have photographed many animals this way by driving around and when a subject is found, my camera is ready for instantaneous use. As long as I stay in the truck, it is possible to catch many birds, mammals and reptiles in their natural environment.

On this particular morning as I was on the road near a man-made reservoir in the protected area, the sun was just peaking over the distant mountains when I flushed a male and female jungle fowl. They flew to a tree about 50 meters away and stayed for a short while as I fired off a long series of photos. But the male was seriously in love and did not pay me any attention as I edged the truck closer for some full-frame shots of the pair. Then the female took flight, and the cock-in-love chased after her but I was ready catching him in mid-flight just off the branch.

Red jungle fowl male with leg band

A close look at the lead photograph will reveal a band around the male’s left leg. This bird was part of a scientific survey carried out by my very close friend and associate Dr Sawai Wanghongsa, and his staff at the wildlife research station at Khao Ang Rue Nai. The rooster was three to four months old when captured about 500 meters away the previous year, and was now full grown and breeding when this photograph was taken in 2009.

But the amazing thing, I could read some of the numbers on the band after enlarging to extreme size in the computer shown in the inset, and Sawai correlated his data about this particular bird. It certainly was a lucky set of photographs including the flying shot of the wary jungle fowl. He has written several scientific papers on the species.

Red jungle fowl in Huai Kha Khaeng WS – A band of cocks

Two sub-species of red jungle fowl live in Thailand. Gallus gallus spadiceas is found on the western flank from the North all the way down to Malaysia, and in the east lives G. g. gallus. The only distinct difference between these two is a white spot on the ear pad belonging to the eastern species, and a red pad on western birds.

Dr Sawai works for the Department of National Parks and collaborates with Japanese scientists including H.I.H. Prince Akishino-no-miya Fumihito of Japan who is studying the relationship between red jungle fowl, domesticated chickens, and the impact humans has upon the wild species. Dr Yoshihiro Hayashi and others with the University of Tokyo and Professor Wina Meckvichai with the Department of Biology at the Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok are also involved in the project.

Red jungle fowl male and females in Huai Kha Khaeng WS

Between 2005 and 2009 they conducted intensive research on the ecology of red jungle fowl in Thailand for the royal multi-disciplinary research project entitled ‘Human-Chicken Multi relationship Research Project (HCMR)’ initiated by Prince Akishino under the royal patronage of H.R.H Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn of Thailand.

They concentrated their studies in Wat Prathat Mae Jedee in Wiang Papao district of Chiangrai province, northern Thailand where the red ear-lobed jungle fowl thrives in strips of forested areas sandwiched between temples and villages where domestic chickens are raised. Parallel studies were also carried out in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife, where the white ear-lobed jungle fowl exist but are more isolated from villages and people. They have gained much evidence about the domestication of chickens. A new program is now underway to further their knowledge and understanding.

Red jungle fowl in Khao Ang Rue Nai WS infested with ticks

Charles Darwin in 1875 speculated that red jungle fowl was the wild progenitor of all domestic chickens and proposed that Southeast Asia was the origin of domestication. Later, genetic evidence supported the Darwin hypothesis in that this species was the main ancestor of domesticated chickens (Fumihito et al. 1994, 1996), and domestication took place somewhere in Southeast Asia, especially Thailand and neighboring areas some 8,000 years ago. Cave paintings revealed chickens were portrayed on a single cave wall in Khao Pla La, Uthai Thani province dating back 2500-3000 years ago.

Prince Akishino was recently in Thailand and granted a Royal Audience by H.M King Bhumibol Adulyadej. Then, the Prince visited Department on National Park (DNP) officials including Sunan Arunnopparat, the Director General who presented a framed copy of the lead photograph to the Prince. It was certainly a great honor for me as the photographer.

Red jungle fowl in Khao Ang Rue Nai WS infested with a tick

Another interesting set of photographs I acquired in Khao Ang Rue Nai of red jungle fowl is a rooster infected with ticks with a large tick on one side latched on to his waddle, and a smaller tick with a load of little ticks on the other side. Males normally have a red crest but this bird looked like it had lost most of its color and was seemingly rather pale.

This was during the dry season and ticks are everywhere latching on to anything that provides blood. It definitely is a dangerous time for human beings as some ticks have harmful viruses that can make one very sick, and has killed people that contracted Lyme’s disease through tick bites. I dread the little critters and get rid of them as soon as possible if they latch on to my skin. I once had one on my left shoulder after visiting Nam Nao National Park in Phetchabun province that became really infected before I got rid of it, and the swelling and itchiness lasted for months.

The Prince of Japan being presented a framed photo by the Director General of the Department of National Parks

Over on the western side of Thailand in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, red jungle fowl are also very common in this World Heritage Site. I am sitting in my battery powered boat-blind up-river about five kilometers from the southern boundary at Krueng Krai ranger station. The sun is bright and warm on this chilly morning. A red jungle fowl male and his harem of two females are pecking the ground for food by the waterway.

I slowly and silently ease the boat closer to get some frame-filling shots of the group. Again, the cock was only interested in the hens and I was able to get quite close. These birds are normally not that easy to photograph.

Prehistorically, the genus Gallus was found all over Eurasia. In fact it appears to have evolved during the Late Miocene/Early Pliocene of Greece and surrounding areas. Several fossil species have been described, but their distinctness is not firmly established in all cases.

As this is about red jungle fowl, the other species like grey jungle fowl G. g sonneratii surviving in India, the Sri Lankan jungle fowl G. g. lafayetii coming from the island of the same name, and green jungle fowl G. g. varius from Indonesia are related.

Male jungle fowl have gaudy iridescent colors but the females come with subtle browns and grays for camouflage. The male have a white rump and legs are grey. The species is found in a wide variety of forest types.

During the breeding season, the dominant male will crow (also known as ek-ee-ek-ek) every hour on the hour. Out of breeding, they only call twice a day, once in the morning and again in the late afternoon. Males form harems in December, and breed from January to May. They nest on the ground and have a clutch of eight to ten eggs. After two months, the chicks will disperse.

The domesticated chicken G. g. domesticus is only mentioned in passing for this story. They of course provide humans with meat and eggs that make up one of our most important protein diets. But now domesticated chickens in close proximity to wild birds have created genetic problems that have arisen in forest jungle fowl at certain locations around the Kingdom.

Nowadays, chickens are involved in many aspects of the normal life of man. Chickens are involved in religious ceremonies as a sacrificial animal, in games as in fighting cocks, in leisure activities as pet bantams, and in the commercial poultry sector as boilers and egg layers. It has been estimated that by 2020, some 83 million metric tons of poultry will be globally consumed every year.

Cock fighting as practiced in the South of Thailand uses specially made daggers that are attached to the rooster’s spur. These extremely sharp weapons are made only from serow horn that has greatly affected this goat-antelope once found in just about every mountain in the Kingdom. Due to hunting for meat and their horns, these unique wild ungulates have also become seriously endangered.

Red jungle fowl is now on the endangered list, and the species like all the rest of the animals living in Thailand’s protected areas need absolute protection. Sweeping changes are needed in its implementation. It seems though the long hard struggle to protect the Kingdom’s forests continues to be an up-hill battle, not only for the DNP, but all the other conservation minded people who love nature. The future of wildlife and the forests remains unclear, and increased budgets, more personnel, better management and education to all levels of society are the key!

Green Peafowl: Thailand’s most spectacular bird

WILD SPECIES REPORT

Beautiful avian fauna thriving in a few protected areas

Green peafowl taking-off in Huai Kha Khaeng

It is a dark misty cold morning along Huai Kha Khaeng, an important waterway in central-western Thailand. The month is November at the beginning of the winter season and the temperature is hovering around 10 degrees Celsius. I’m sitting in my boat-blind with a silent electric trolling motor waiting for the sun to come up, and I’m after wild water buffalo and green peafowl hoping for some good photographs of these two rare species.

At dawn, a green peafowl calls out from its roost reverberating through the valley. The resounding braying can be heard repeatedly many kilometers away. It is nature at its finest that has gone on for thousands of years. I motor the boat closer and find a flock of peafowl pecking the ground by the river and looking for anything edible.

Green peafowl flock by Huai Kha Khaeng in late afternoon

As light begins to fill the river valley, I move in closer to the peafowl on a large sandbank. A male takes-off and lands close to the flock immediately opening up its tail in a shimmering fan display. The females and younger birds are busy pecking the ground.

During the breeding season, the male peafowl’s iridescent tail called a train, are long and graceful. He struts along the riverbank showing off to the females hoping to impress the flock. Several other males are nearby also flaunting their tail spreads to incite the other gender.

Green peafowl male by the Huai Kha Khaeng in early morning

The blue and yellow facial skin, plus the emerald green and metallic blue of its feathers with cinnamon colored wing primaries contrasting with brownish-black secondaries is a sight to see, especially during the soft early morning light and again in the evening glow at sunset. They are the most spectacular of all Thai birds thriving fairly well in this wildlife sanctuary, a World Heritage Site. The species can also be found in a few other protected areas around Thailand.

Green peafowl male by the river in Huai Kha Khaeng

Birds evolved from dinosaurs: there is no doubt about that. The evolution of birds probably began about 150 million years ago. The earliest known bird was Archaeopteryx, which was the size of a modern crow and lived in the Late Jurassic. Fossil evidence found in Germany indicated it had feathers arranged over its body and its wings; and though not as agile as a modern bird, could probably fly well. It also had a dinosaur’s jaws with teeth, claws on its hands, and a long reptilian tail.

Throughout the succeeding Cretaceous period all kinds of dinosaur-bird hybrid animals existed, but their exact relationships to one another are not really known. In the 1980s and 1990s fossils of these animals began to be discovered in South America, Spain, and particularly in China. However, there have been no discoveries of these bird-like creatures in Thailand, but more than 15 species of dinosaur have been uncovered here.

Green peafowl male flaunting its tail spread

Green peafowl probably evolved from red jungle fowl, the ancestor of all wild and domestic fowl. Jungle fowl is believed to have come to being some 800,000 years ago. It is not exactly sure when peafowl came about but it is thought to be sometime around 500,000 years ago.

Red jungle fowl in Huai Kha Khaeng – western species

Red jungle fowl in Khao Ang Rue Nai – eastern species

King Rama V wrote about seeing green peafowl at Muang Sing in Sai Yok district of Kanchanburi province during a Royal visit there. Rock paintings discovered in Lampang province in the North about 3,500 to 5,000 years old show a peafowl with long tail-feathers on a cliff-face. These majestic birds have been featured in many stories and legends throughout the history of the Kingdom.

Rock painting showing green peafowl 3,500-5,000 years old in Lampang

The green peafowl, also called Javan peafowl, Pavo muticus is a large galliform bird found in the tropical forests of Southeast Asia. It is the closest relative to the Indian peafowl or blue peafowl Pavo cristatus, which is mostly found on the Indian subcontinent. Peafowl are smaller than the American turkey.

In the past, the distribution and habitat of the green peafowl was widely scattered, from eastern and northeast India, northern and southern Myanmar, and southern China extending through Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Peninsular Malaysia and the island of Java. These ranges have been drastically reduced through habitat destruction and hunting.

Green peafowl male and flock at Huai Hong Krai Royal Project in Chiang Mai

According to J.H. Riley with the Smithsonian Institute who published ‘Birds from Siam and the Malay Peninsula’ in 1938 reported green peafowl could be found in most forested areas and alluvial rivers in Thailand. There are two sub-species: the Pavo muticus muticus south of the Isthmus of Kra, and P. m. imperator to the north. Unfortunately, they have vanished from the Northeast and the South, and from Malaysia. The Burmese P. m. spicifer is a more drably colored bird.

One person who has researched green peafowl in depth is Professor Wina Meckvichai with the Department of Biology at the Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok. She has studied populations and behavior of the peafowl, and other gallopheasants like red jungle fowl in the country.

Young male peafowl by Huai Mae Dee in Huai Kha Khaeng

Presently, there are about 2,000 wild green peafowl left in the country and most are in the western forest complex mainly in Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai Naresuan wildlife sanctuaries, and Sri Nakarin National Park. They may also be found in other protected areas in the west but these would be small isolated populations.

Peafowl can also be found in the Northern provinces of Nan, Phayao and Chiang Mai. A few may survive in the Salaween Wildlife Sanctuary along the river and border with Burma, but there are not many reports whether the species exists west of here.

Juvenile peafowl late in the afternoon in Huai Kha Khaeng

The overall population of peafowl in the north is decreasing due to human disturbance but is slightly increasing in the west. However, at Huai Hong Krai Royal Project at Doi Saket district in Chiang Mai province, peafowl are also on the increase due to special protection provided by the project.

About 25 years ago, I saw a male green peafowl with long tail feathers during the breeding season in Sai Yok National Park, Kanchanaburi province by a tributary of the ‘Noi’ River deep in the interior. However, they have not been seen or heard here for years now.

Female peafowl in Huai Kha Kha Khaeng

Hunters have poached the birds for their meat and tail feathers, and wiped them out in many areas throughout the country due to increased access into the protected areas by local villagers and ethnic tribes people. Encroachment on forestlands has also been heavily responsible for the disappearance of this beautiful bird.

During most of the year, when the males have no visible trains, both male and female green peafowl are quite similar in appearance, and are difficult to distinguish between the two. Both sexes have tall pointed crests, and are long-legged, heavy-winged and long-tailed in silhouette. The long train formed by elongated upper tail coverts, spread in an enormous fan during display. These molt and drop out in April and May during the hot season.

Huai Mae Dee – green peafowl habitat in Huai Kha Khaeng

The peafowl’s peculiar flight has been described, as a true flapping flight with little gliding that is usually associated with other Galliform birds. With a wingspan of 1.2 meters across, peafowl are capable of sustained flight.

According to ‘A guide to the Birds in Thailand’ by the late Dr Boonsong Lekagul and the eminent ornithologist Philip D. Round, peafowl are found in several different habitats including mixed deciduous woodland, secondary growth and clearings usually close to shallow streams or rivers with exposed sand bars, plus foothills and plains, but occasionally higher plateau areas. At the time of publication in 1991, peafowl were considered a rare resident much reduced by human persecution. Peafowl adapted to a changed habitat in Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai flooded by the Sri Nakarin Dam and reservoir in the west.

Green peafowl spend most of their time on or near the ground in tall grasses or sedges. They forage for food in open areas and along riverbanks. Family units roost in trees about 10-15 meters off the ground. The Green Peafowl is a forest bird that nests on the ground laying three to six eggs.

Their diet consists of fruits, invertebrates, reptiles and other small animals. Adult birds hunt for ticks, termites, flower petals, bud leaves and berries, and are also known to take poisonous snakes from time to time. Frogs and other aquatic small animals probably make up the bulk of the diet of growing birds.

Although rare compared with historic numbers, improved survey methodology and increased effort has led to an increase in the reporting rate and thus the population estimate has been revised upwards to reflect this improved knowledge. Nevertheless this remains a coarse estimate and it warrants refinement.

Continue research into its range, status, habitat requirements and interactions with people to inform management within the protected areas should be carried out. Peafowl require strict enforcement of regulations relating to hunting and pesticide used within the parks supporting populations in Indochina. A total ban should be encouraged on the international trade in live birds and tail feathers in all range countries.

Because of its attractive appearance, the green peafowl faces the threat of hunting or as pets. Its feathers are considered to be valuable art objects and are also popularly used in household crafts and decorations. It is listed on Appendix II of CITES, and before 2009, it was evaluated as ‘vulnerable’. The bird is now listed as ‘endangered’ on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. The world population has declined rapidly and the species no longer occurs in many areas of its past distribution.

As with all other wild birds and animals living in the protected areas, the green peafowl in Thailand is in a serious predicament. More and more people forage in the forest and along with this, poaching is a never-ending saga. Protection and enforcement is the number one priority for the government but recent protection budget cuts have been tabled which in the event go through, will seriously affect all wildlife and their ecosystems.

It is also said that many temporary rangers will be lose their job if these budget cuts go through, and to compensate them, a scheme has also been tabled where the rangers join forces in their respective villages, put in a bid to look after the forest similar to the community forest program, and then wait for the wheels of doing business here. This is the beginning of the end.

Corruption will certainly come into play and these jobless rangers who already know the forest, will slip into areas they know well and, poach and gather. There will be no unity within the ranks to properly maintain a good protection program. With big money, continued and expanding wildlife trading, and other dark political forces at work, plus an ever-expanding human population, it will be a rough road ahead.

It is unfortunate but the future of the green peafowl is in the balance, and if management, funding, protection and enforcement are not increased and improved, these spectacular birds will slowly and eventually go the way of the dodo in New Zealand and the carrier pigeon in the United States. The government of Thailand should do much more in taking care of the Kingdom’s great wild heritage.