Archive for January, 2010

The Indochinese Tiger: Lord of the Jungle

Wild Species Report

Thailand’s mystical cat – A rare striped carnivore and awesome natural predator

Falling leaves signals the dry season has arrived and the forest floor is carpeted with a mosaic of green, yellow, brown, red and orange. A large predator walks the trails seeking its next meal. A barking deer sensing danger barks a warning. The whole community of wild animals is on alert as squirrels and monkeys cry out from the trees above. A striped carnivore stalks a herd of wild pigs. The nervous omnivores squeal and panic, running through the underbrush to escape. But the big cat is quick as lightning – it catches a young pig with sharp claws. The struggle is over in seconds as fangs penetrate to the spine.

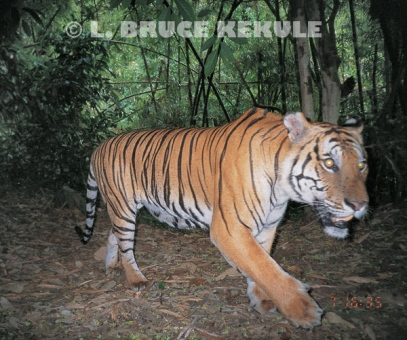

Indochinese tiger Panthera tigris corbetti in Huai Kha Khaeng

A tiger has just made a kill. It lifts the lifeless pig into deep cover and devours the carcass. After feeding, the big cat will seek water for a thirst quenching drink. It will lie down and rest until the desire to eat or drink begins again. Tigers sometimes move great distances in search of food. But where there is an abundance of prey, tigers continue to live in balance with nature. The average kill ratio is about twenty unsuccessful attempts to one kill. At a certain time of year, the male tiger will seek out a female in estrus to carry on his legacy.

Some two million years ago, the tiger evolved in Northern China and Siberia, and spread to many parts of Asia all the way to the Caspian Sea and eastern Turkey in the west. The Himalayas stood as a serious barrier to their migrating into India. Some reached Korea and Manchuria, and also advanced south through China then into Indochina, and down to the islands of Sumatra, Java and Bali. Tigers are good swimmers and made it across narrow sea channels. About 10,000 years ago, the big cat moved west through Burma and Bangladesh on to India. At one time, there were probably more than a hundred thousand of them throughout the tiger’s world range.

Tiger on the prowl in late afternoon

A century ago, Thailand was an absolute haven for this carnivore. They could be found in every forest within the Kingdom. But as humanity expanded, the species quickly declined because of human predation, and loss of habitat and prey animals. The pelt is sought after by hunters and its bones wanted by Asian medicine practitioners. Many considered this predator a pest and as modern weapons became available, and humans expanded into the forest, these magnificent beasts really began to vanish. Realistically, it is estimated there might be about 200 to 300 tigers left in Thai forests, which unfortunately, is barely sustainable over the long run in some areas. However, a very few protected areas if properly taken care of, could sustain a population of tigers. Thailand still retains some of the best-protected tiger habitat left in Southeast Asia. Wildlife corridors between protected areas are one of the most important keys to sustainability.

Feral cats caught by camera traps on a wall behind my home

When I began wildlife photography, the burning desire to photograph a tiger in the wild was one of my great wishes. These cats are extremely difficult to see let along photograph. My real first encounter with a tiger was in Sai Yok National Park in western Thailand back in 1996. I was sitting in a tree-blind when one jumped across the stream behind me and I caught a very brief glimpse of the sleek cat as it moved downstream hunting for prey. From that day on I photographed many other wild creatures including the leopard, but never a tiger. I was beginning to doubt whether I would ever photograph one.

My first camera trapped tiger in Sai Yok National Park

Several years later coming back to Sai Yok, I began a camera trap program not far from the headquarters. This was in mid-October 2003. Six traps were set-up in the forest at waterholes and game-trails. As we were breaking camp, the cook asked me for a lucky number. I just lifted my camp chair that left two impressions in the dirt like the numeral 11, and so I called out 11.

My second camera trapped tiger in Sai Yok

A month later, the film and batteries were collected and after processing, I saw two tigers on film. The first was an old male caught at a waterhole on the 11th day of the 11th month that was recorded on the frame. Three days later, a younger male tiger passed another camera up on a 600 meter ridgeline on the 15th at 16.11 pm also imprinted in the frame. Some may say it was just a coincidence to have the number 11 in both photos, but I like to think the ‘spirits of the forest’ had finally answered my prayers.

Tiger camera trapped in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Further south along the Tenasserim Range in Kaeng Krachan National Park at the beginning in January 2001, I began another camera trap program in conjunction with World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF) and the Department of National Parks (DNP) at two locations in the park. The first was along an old logging road not too far from the main gate at Sam Yot. During a four-month period, many animals were captured on film including an amazing six photographs of one mature male tiger. He actually came right up to the camera trap for a facial portrait, and then walked away. That was the beginning of a very successful ‘presence/absence’ program carried out (2001-2004) to determine if tigers and other large mammals were still surviving here.

Tiger male hunting on an old logging road in Kaeng Krachan

The second area was along the Phetchaburi River that flows crystal clear through this magnificent forest. Many tigers walk the elephant trails hunting for prey. My very close friend Sutat Sapphu (a forest ranger with incredible knowledge of this ecosystem) and I began a monthly program setting up more than 20 cameras along the river. One particular individual tiger named ‘four-spots’ due to a marking on its left flank was caught down near a crocodile pond where he actually tried too bite a camera trap and we got a shot of his mouth and whiskers. Over the next few months, ‘4-spots’ was captured up and down the river, and then way up Phanern Thung Mountain at 900 meters by the road into the park at kilometer 28.

Tiger camera trapped on old logging road in Kaeng Krachan

When the road was closed in Kaeng Krachan due to heavy storms and landslides in October 2003, four-spots was consistently camera trapped at kilometers 33, 34 and 35, and down at the infamous ‘KU’ camp by the river. The distance was calculated to be about 22 kilometers apart. Several other male and female tigers were recorded over the three-year program and are a testament to the remarkable biodiversity of Kaeng Krachan. Many other creatures were also caught including tapir, leopard, wild dog, fishing cat, sun bear, the rare Fea’s muntjac, elephant, gaur and serow among others. Returning in November 2008, and now using a digital camera trap, I got a tiger in November at a mineral lick just 12 kilometers from the front gate.

Tiger up-close in Kaeng Krachan

Good things sometimes come our way and I was about to get a reward to coincide with ‘2010-The Year of the Tiger’. The absolute chronology of being at the right place, the right time with the right equipment and the right technique was played out before my eyes. On the 11th of December 2009 (my lucky number again), the tiger in the lead photo and I crossed paths. I was lucky to have been sitting down with my hands on my lap right in front of my camera. If I had been standing, or made just the slightest noise, I would have never seen this old male.

Indochinese tiger on the prowl at night

The trail through dry dipterocarp forest takes about a 40 minute walk to a photographic blind set above a mineral deposit deep in the interior of Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand’s top protected area and World Heritage Site situated in western Thailand. The flimsy structure made of bamboo sits about two meters off the ground and is attached to a tree. Black mesh closes off the cubicle on all four sides that was erected by the park rangers. An opening large enough for a big lens allows a clear view of the waterhole some 50 meters downhill to a saucer shaped depression.

Tiger at night by the Phetchaburi River

This waterhole attracts many creatures such as elephant, gaur, banteng and other ungulates like sambar and wild pig. Tiger, leopard and Asian wild dog also come looking for prey. It is truly a magical place and a tribute to Thailand’s natural biodiversity. Arriving about 12pm, I immediately set-up my cameras and then waited. Feeling dozy, I strung my hammock for a bit of a snooze after the long haul from Bangkok. The afternoon passed-by slowly and about five got up and began a vigil of the mineral lick. A few minutes later decided to actually sit behind my 400mm lens and camera, and do some adjustments to compensate for the fading light. Took a few test shots to make sure the exposure was correct and then waited. Two minutes later, the dream of a lifetime unfolded before me.

Same tiger a month later during the day at the above location

A striped carnivore magically and silently appeared from the forest on my right. The tiger walked straight down to a little stream for a quick drink. The mature male did not linger and continued on his way. However, he did pause briefly to stare up at my position three different times before disappearing into the forest on my left. Total time spent by the cat at the waterhole was less than a minute. I was extremely fortunate to snap 20 frames as the magnificent creature carried on its way. I banged my head against my camera in disbelief to make sure I was not dreaming. After 15 years of wildlife photography, my aspiration to photograph a tiger through the lens has finally come true.

A female tiger in early morning at the same location

The present status of the tiger in Thailand is balancing on the beam of nature. As a World Heritage Site, Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai Naresuan wildlife sanctuaries is the core area and absolutely the last great tiger haven in the Kingdom, and Southeast Asia for that matter due to its size (6,427 square kilometers), and its biodiversity. In Huai Kha Khaeng, the Department of National Parks has really improved the situation with better patrolling, increased help for the rangers, a demarcation fence along the eastern buffer zone in Uthai Thani, constant vigilance by many people and NGOs’ plus improved management, wildlife research and better awareness education. With these measures in place, prey species have come back and are now abundant. Tigers are thriving. There are about a hundred in the Huai Kha Khaeng-Thung Yai block.

Male tiger posing for my camera

Research on the tiger has been carried out by the Wildlife Research Division under the direction of Dr Saksit Simcharoen and his staff in conjunction with several other people and organizations including Dr Ullas Karanth (from India) and Dr Dave Smith from the University of Minnesota.

A waterhole with mineral deposits in Huai Kha Khaeng

Dr Saksit and others has published a paper in the science journal Oryx (How many tigers Panthera tigris in Huai Kha Khaeng: An estimate using photographic capture-recapture samplings) to establish a number. According to Dr Saksit, the home range of the Indochinese subspecies is about 240 square kilometers. Dr Peter Cutter with WWF-Thailand, and also a student with the University of Minnesota, has done his doctorate thesis on ‘tiger’s occupancy monitoring’ using transect and trail sign data gathered in Huai Kha Khaeng.

Tiger entering waterhole

Camera trapping is still by far the best and safest way to establish a home range of a tiger due to its individuality. No two tiger’s striped pattern is alike. It is imperative to use opposing camera traps to get a picture of both sides to identify individuals. Footprint and scat analysis are also very good techniques.

Tiger drinking from shallow stream

In my opinion, collaring a tiger is extremely dangerous as the capture process could possibly injure or impair the animal. As rare as they are, it does not justify losing even one of these magnificent creatures to a possible botched captures and release. Some researchers may not agree but eight tigers in Huai Kha Khaeng have already been collared and ranges determined. You can only get so much data. Loads of tiger home range information has also come from India and elsewhere. I’m all for good passive scientific research (wild animals are not handled at all) carried out to save the tiger.

Tiger looking back at my position

The Western Forest Complex includes 17 protected areas encompassing more than 18,000 square kilometers and has the potential to accommodate 700 tigers. Even though this estimate is high, with good protection and patrolling in all the protected areas in the complex to keep poachers out and encroachment to zero, and to protect the prey species or food chain for the tiger, it is feasible in the future this number could be a reality. However, due to serious fragmentation with roads, dams and reservoirs plus humanity and agriculture, it will be a difficult road ahead unless the present boundaries of the large protected areas stay intact and unharmed, and more corridors set-up through national forests. The World Heritage Site of Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai must be the number one priority of the DNP as a conservation area.

Tiger on the move

For the long run, forest protection and wildlife awareness education to all levels of society is the key to saving the Kingdom’s natural heritage. The government should always strive to use all its resources to keep the forest and wildlife free from the damaging effects of human intervention. The private sector and the government need to be aware of all the problems regarding the forest rangers and try to improve their lives. The forest can be a deadly place to work and these men need incentive, as they put their lives on the line.

Tiger’s final look before disappearing into the forest

Projects to provide food and clothing to help these men are being carried out in a few protected areas by a few individuals, companies and organizations. Without dedicated ranger patrolling, tigers will surely slip away. It is up to the present generation to take proactive measures to make sure Thailand’s wild flora and fauna stays intact for future generations to see, enjoy and cherish.

Ecology and behavior of the Tiger:

To understand how the tiger evolved, we must go back to the beginning of these wild creatures. Nimravidae were the first cats to evolve in the Early Oligocene epoch, about 35 million years ago. They lasted till the Late Miocene, some eight million years ago, when huge grasslands had developed around the world. The large saber-toothed cats were the first of the family Felidae. These long-fanged felines evolved alongside huge herds of grazing mammals like antelope and cattle. There were several different species of saber-tooth, but they all became extinct about two or three million years ago.

Modern cats belong to the family Felidae which includes: tiger, lion, leopard, cheetah, and domestic cats. Ultimate carnivores, they feed almost exclusively on vertebrate prey and sit at the top of the food chain. Wild cats have few predators apart from man. The tiger belongs to the genus Panthera or roaring cats that also includes the lion, leopard and jaguar.

Tiger camera trapped abstract

The Indochinese tiger Panthera tigris corbetti was named after Jim Corbett, the famous conservationist and hunter of man-eating tigers and leopards in India during the 1930s’. This subspecies is found in Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, eastern Burma and southeastern China. According to Chatchawan Pisdamkham, Director of the Wildlife Conservation Division of the DNP, there are approximately 250-300 tigers left in the wild of Thailand.

The following protected areas still harbor these magnificent felids: Huai Kha Khaeng, Thung Yai Naresuan, Umphang and Salak Phra wildlife sanctuaries plus Mae Wong, Sai Yok, Sir Nakarin, Erawan, Kaeng Krachan and Kui Buri national parks in the west; Khao Yai, Thap Lan and Pang Sida national parks, and Phu Khieo wildlife sanctuary in the Northeast, and Hala Bala Wildlife Sanctuary in the deep south.

Tiger camera trap abstract

It is doubtful if any tigers survive in the protected areas of the north or Khlong Saeng-Khao Sok forest complex in the south as no reports have come from these areas for many years. Eastern Thailand has no tigers on record. A couple of years back, the newspapers reported on tiger tracks found not far from the road around several national parks in Chiang Mai and Lampang but were fake put down by a prankster to stir-up media frenzy. This was supposedly to help villagers who had lost cattle to a predator, more likely feral dogs.

Tigers are essentially solitary but come together when a female is in estrus. The resident male will copulate with a female many times over several days. Gestation ranges from 93-114 days. Litters can be from one to seven but usually only two to three cubs survive. Tigresses rarely accompany more than three cubs in the wild and abundant prey is required for a growing family with a small home range about 60 square kilometers.

Indochinese tiger tracks in Kaeng Krachan

It has highly developed vision about six-times more powerful than man and an extreme sense of hearing. These attributes are essential in locating prey. The feed almost exclusively on herbivores and are at the top of the food chain.

Indochinese tiger habitat in Kaeng Krachan

The tiger’s ultimate advantage in stalking prey is its striped pattern that is natural camouflage and this cat is a very efficient killer. It has awesome strength and unmatched armament of retractable claws, long fangs and dagger-like canines. It can sometime dispatch animals as large as gaur, wild water buffalo and small elephants. Tigers have no predators other than humans.

Asian Elephants: Thailand’s Mega Fauna

Wild Species Report

A flagship species and cultural symbol

Thailand’s largest terrestrial animal on the brink of extinction

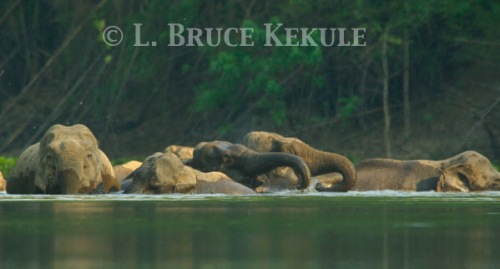

Wild elephant family unit in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Santuary

In 1927, a film was made depicting wild Thailand, and shown to audiences around the world. Entitled ‘Chang – A Drama of the Wilderness’, this epic documentary was produced by two American filmmakers Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, and released by Famous Players-Lasky, a division of Paramount Pictures.

‘Chang’ (Thai for elephant) is a melodrama and silent film about a man, the jungle, and wild animals as its cast. The main character is Kru, a poor farmer depicted in the film that battles tigers, leopards, bears and even rampaging elephants, all of which pose a constant threat to his livelihood. The saga was depicted in the northern province of Nan where thousands of wild elephants survived in vast herds at the time. The footage of elephants in the hundreds is remarkable.

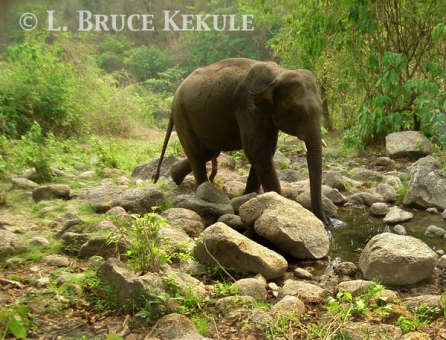

Young tusker at a mineral lick in Huai Kha Khaeng

The film also shows tigers and leopards caught in pit-falls and dispatched with a muzzleloader from the top. It was an amazing piece of celluloid production where logistics must have been really tough. Chang was nominated for an Oscar for Unique and Artistic Production at the first Academy Awards in 1929. Cooper and Schoedsack went on to make the classic blockbuster movie King Kong.

Tusker in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

The Asian and African elephants are the only two surviving species of a once diverse and widespread group called proboscids (order Proboscidea), or animals with a trunk. They are characterized particularly by developments of their teeth and adaptation of their limbs for supporting their increasing mass. All total there is fossil evidence of some 350 species of ancestral proboscideans, mastodons, mammoths and modern elephants.

The first ancestor of elephants lived approximately 50 million years ago during the Late Eocene and Early Oligocene Epochs. It was named Moeritherium after the place where it was discovered, the Moeris Lake in Egypt. Though its form and appearance were completely different from the elephant, scientists base Moeritherium’s ancestry of the elephant on its skull and teeth. The skull had air holes, just like the elephant, and four small incisors grew from the upper and lower jaw that the growth of tusks had begun. At least three divergent groups of proboscideans evolved there from Moeritherium or close relatives.

Mature tusker camera trapped at a waterhole in Khao Ang Rue Nai

The next beast of elephantine build and bulk was the Deinotherium that was still not a true elephant. They became common in Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe during the Miocene Epoch. They were very large at 4 meters high with down curving tusks from the lower jaw. Surviving for 20 million years well into the Pleistocene Epoch, Deinotherium was clearly a very successful animal. About the same time Paleomastodon and Phiomia began to evolve and show the closet beginnings of a trunk allowing the species to feed higher off the ground.

Very old tuskless bull in Huai Kha Khaeng

At the beginning of the Miocene epoch about 24 million years ago, the ancestral Gomphotheres was the real commencement of Proboscidean diversity. There were literally hundreds of species at one point including mastodons and mammoths. Elephantidae is the family to which the modern elephant belongs and the first species was Elephas antiquus from the middle to late Pleistocene Epoch. However, by the beginning of the Holocene Epoch around 10,000 years ago, only two species remained: African elephants Loxodonta africana and Asian elephants Elephas maximus.

Tusker in Khao Ang Rue Nai

The main differences between the two species are anatomical. The African elephant are larger and has a more elongated skull, a trunk with deep rings, larger ears, a flat forehead and, in general, holds its head at a 45 – degree angel to the ground. Asian elephants are smaller and have a double – bulged forehead, a trunk with fewer rings, smaller ears and a skull with a 90 – degree orientation.

There are three Asian sub-species: the Sri Lankan elephant Elephas maximus maximus, the mainland elephant Elephas maximus indicus, and the Sumatran elephant Elephas maximus sumatranus, and two African sub-species: the bush elephant Loxodonta africana africana, and the forest elephant Loxodonta africana cyclotis.

Young tusker camera trapped at a waterhole in Huai Kah Khaeng

Prehistoric fossil evidence of proboscideans has been discovered in the north, the northeast, the central plains, and the south of Thailand. The first find in 1948 was fossil bones of Stegodon insignis (mastodon) during the construction of the bridge across the river just south of Nakorn Sawan provincial city. Following this, discoveries were made in lignite deposits in Lamphun, Lampang and Phayao provinces. Fossil teeth of a Deinotherium at Ban Sop Khan in Phayao have been uncovered. Another find new to science is the earliest known species Stegolophodon praelatidens fossils from the Early Miocene discovered in Lamphun and Lampang by Pascal Tassy (from France) and others.

Many extraordinary ancient proboscidean fossils have been unearthed in Nakhon Ratchasima (Korat) province at the Tha Chang and Chang Thong sand pits along the Mun River in Chaloem Prakiat district going back to the middle Miocene about 16 million years ago. Eight different genera of proboscideans have been discovered here and is a testimony to the Kingdom’s fossil record.

Family unit in Huai Kha Khaeng

About 150 years ago, wild elephants were surviving around Bangkok along the Chao Phraya River, and in the districts of Rangsit, Bang Sue, Bang Kapi and Bang Na. The ‘City of Angles’ was a real jungle back then. It seems difficult to believe but in those days, Thailand was almost completely covered by forest cover – more than 90 percent. Today, only 30 percent remains. Due to the immense destruction, elephants have been at the forefront of a disappearing habitat.

The best current estimates say there are no more than 2,500-3,000 elephants surviving in the wild of Thailand today. There are 60 protected areas that have less than a hundred elephants, and another eight protected areas that have over one hundred individuals as follows: Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary – 280-300; Khao Yai National Park – 200; Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary – 230; Salak Phra Wildlife Sanctuary – 175-200; Phu Luang Wildlife Sanctuary – 100; Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary – 135; Kui Buri National Park – 150 and Kaeng Krachan National Park – 115. Surely, an up-to-date consensus of the wild elephant population should be undertaken by the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP) in all the forests throughout the Kingdom, and a report published as soon as possible. As it stands, many of these quotes are mere guesstimates.

Young tusker on the road in Khao Yai National Park

Elephants have been persecuted for a long time. The following scenario has been chosen for this column and has been carried out for decades in Thailand’s forests, and unfortunately is the dark side of nature that carries on to this day. Gunshots reverberate explosively through the forest panicking and scattering a herd of wild elephants. The huge beasts instinctively flee as fast as they can through heavy foliage away from the cacophony. In minutes, the forest returns to normal but the sad fact is humans have just disrupted the herd permanently. A baby elephant mills aimlessly around its mother lying dead on the ground. The confused calf has no sense of danger as poachers move in and capture it to be sold on the illegal black market. The calf will likely be forced to wander city streets or work in tourist camps.

Such atrocities are still practiced by some unscrupulous people intent on killing the mother solely to capture the baby. Many other animals are also hunted down in much the same way like gibbons and monkeys. Middleman and end-use buyers perpetuate this market and seem to evade the law. Wildlife black-market trading is fueled by a few shady individuals and is on-going. Great strides have been achieved by a few wildlife enforcement agencies and many arrests have been made in recent years exposing these law-breaking individuals. However, the so-called ‘big fish’ continue to do business as usual. It is a never-ending battle!

Mature tusker on the road in Khao Yai

In another scenario, a mature bull elephant with a large set of tusks tramples and gores a man deep in a protected forest many days walk from the nearest village. News travels fast but is subdued by the authorities due to the sensitive nature of the incident. The man was with a group of poachers hunting the tusker and he was armed with a crude muzzleloader. He was separated from the group and came upon the huge herbivore firing a shot, which only enticed the old bull to charge. It was all over in seconds and when the man was found critically injured the group rushed him to the nearest medical facility but it was too late. The villagers cried fowl and hunted the old bull down eventually taking his tusks and selling them to a middleman for pennies compared to what they would fetch from a rich end-user or agent. This has been going on for ages to feed the illegal ivory trade.

Human settlement, agriculture and roads have taken over much of the elephant’s habitat. Villages spring up in old elephant terrain, and the trespassers expect the giants to simply fade away into the forest. But elephants can develop a taste for crops grown by farmers, and they often take what they want. Countless conflicts have arisen between villagers and the real owners of the land, whose ancestors have lived there for many thousands of years. Thailand is not alone to crop-raiding elephants. Other countries in Asia and Africa have experienced the same outcome when humans have taken over elephant land.

Very young tusker about five years old in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

Most of the conservation areas where wild elephants live are just small isolated pieces, and agricultural areas or towns surround these forests, a major obstruction to natural breeding. Elephants in each forest are caught on islands and cannot walk back and forth between these areas. Thus, inbreeding among close relatives is inevitable, which leads to an inferior population and causes genetic diseases, and ultimately, to extinction. Belinda Stewart-Cox with Elephant Conservation Network has campaigned relentlessly for the establishment of a corridor between Salakpra and Srinakarin protected areas in order to prevent the total isolation of Salakpra’s elephants. Other corridors in other parts of Thailand are on the drawing boards.

The young tusker a month earlier

Elephants have been maimed and killed by poisoning, pungee stakes and pit-falls, gunshots, and electrocution. They have been chased out of rice paddies, mango orchards, and pineapple and tapioca fields. The use of fireworks, bright lights and gunshots scare them away temporarily, but the elephants are intelligent enough to lose their fear of such ruses. Elephants grow bolder and go on the rampage, sometimes killing people, tearing up villages and damaging DNP facilities usually during the dry season when water is scarce.

Nick-named ‘Nong Saeng’ after the sanctuary

This year, a herd of wild elephants in a western national park raided a village and broke into a shack with fertilizer. A young calf gorged itself and died shortly thereafter. On the other side of the spectrum, an old tuskless bull killed a ranger in western Thailand, and a tusker gored a villager in the East. Wild elephants have also died or been injured accidently by vehicles speeding on roads in some protected areas. Most of the accidents occur at night when the elephants are difficult to see. Some conservation organizations have erected new signs in some areas warning drivers the danger of elephants on the road at night.

Mature tuskless bull in Kaeng Krachan National Park

These noble beasts have featured prominently in almost every important historical event in the Kingdom. They are national, royal, and religious icons of Thailand. The ‘white elephant’ was on the flag of Siam. They are a national symbol of pride and joy. The Thai elephant’s survival lies in the hands of those responsible for these vanishing Asian giants. Proactive conservation awareness is a top priority for the government and existing outdated laws (some a hundred years old) need to be reviewed and changed for the elephant’s future. Strict penalties and fines for poaching and encroachment need to be enforced to insure the survival of nature’s largest terrestrial mammal in Thailand before it is too late.

Ecology and behavior of elephants:

“Tractors of the forest” is what the late Mark Graham called wild elephants in his excellent book entitled ‘Thailand’s Vanishing Flora and Fauna’ co-authored by Philip Round, the eminent bird ornithologist. Graham went on to say “in all parts of Khao Yai National Park there are trails which have been used by herds of elephants for, in all probability, thousands of years”. This trait is evident throughout continental Thailand where these creatures roamed.

Tusker about 25 years old in Kaeng Krachan

Asian elephants consume 75-150 kilograms of food and about 80-160 liters of water per day. A variety of grass species including bamboo is consumed, as well as tender twigs, barks, leaves and fruit. Natural mineral deposits are also very important to these herbivores supplementing their diet. An adult mainland Asian elephant may reach a height of 3.5 meters and weigh 5,000 kilograms. Elephants form family units but lone bulls are common. Male elephants have tusks but tuskless bulls are now quite common and can be very bad tempered, especially if the bull is in a state known as ‘musth’ where fluid leaks from the temporal gland.

Mature tusker at a waterhole in Khao Ang Rue Nai

Reproduction of the Asian elephant is the same as the other sub-species. The young are born after a gestation period of 18-22 months. Elephants usually give birth to a single offspring, rarely twins, and more rarely triplets. A female elephant can give birth every 4-6 years, and has the potential of giving birth to seven offspring in her life. Life expectancy for elephants is 60-70 years.

Elephants in domestication:

Elephants are extremely intelligent creatures. For centuries, humans have taken elephants from the wild and turned them into many different uses such as war elephants, working elephants at logging sites, as pets, tourist attractions and street beggers.

Elephant on the highway in Ayuttaya province

My very close friend Richard Lair who works for the Forest Industry Organization at the Conservation Center in Lampang has worked with elephants for many years. He was the first to get elephants to paint in Thailand, and the first in the world to establish a musical band made up entirely of elephants. He has produced several CD’s of this accomplishment.

Begging elephant near the 700 year stadium in Chiang Mai

Probably the most appalling fate for a domesticated elephant is to become a ‘street walker’. These magnificent creatures are forced to saunter hot, dusty and polluted streets of Thai cities ‘begging’ for food and money. Stories about elephants hit by cars and falling into drainage ditches, plus other accidents have been documented. At one time, a trip at night around Bangkok and other cities in the Kingdom one was greeted by a huge gray beast with a red light and a flashing CD attached to its tail. Continuous calls for change went unnoticed by mahouts and the owners of these elephants who sneaked them into cities and tourist sites. Legislation concerning domesticated elephants remains old and out-dated, and law enforcement has also been very poor.

Domesticated elephants being trucked into Chiang Mai

In late-2010, I saw an elephant on the streets of Chiang Mai at night. I took a few photographs but just watched as the mahout and elephant went about their business of begging for money. However, the situation has improved and there are several new sanctuaries dedicated to helping both mahout and elephant. It seems that most of the elephants have left Bangkok but they are still found in the out-lying areas. Hopefully, one day, the street-walker will be a thing of the past and these magnificent creatures will be treated with the respect, love and admiration they deserve.

Elephant with handlers on the streets of Chiang Mai – An abstract