Archive for the ‘Wild Species Report’ Category

Indochinese Tiger: How I capture tigers on film and digital

|

“This is an old post but I thought it would be good to re-cap my work over 20 years with the tiger” Notes from the field: The wizardry of modern technology |

Tiger posing in a waterhole in the Western Forest Complex of Thailand…!

I arrived in Thailand in 1964 and took an immediate liking to the wildlife and forests of the Kingdom. Since then I have consistently visited many wilderness areas, and I can say the tiger is the most difficult of all the Asian creatures to see or photograph. I have only seen two tigers in all those years although many have been seen on my camera traps. Also, I have come upon many tracks left by the big cats. These magnificent carnivores are now rare and hence, very difficult to capture on film and/or digital. However, the wizardry of modern technology has given me an edge.

Male tiger camera trapped in the Western Forest Complex

My first sighting of a tiger was in Sai Yok National Park in Kanchanburi province along the western border with Burma more than 15 years ago, and my second in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Santuary in Uthai Thani province just last year. Western Thailand is probably the best place where tigers can be seen in the wild. Luck would have to be the number one element but photo equipment, know-how and location also come into play.

Tiger camera-trapped at night by the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan National Park

The first was a fleeting glimpse of tiger deep in the forest of Sai Yok Natonal Park in Western Thailand as I was sitting in a tree blind overlooking a large stream and mineral deposit, waiting for gaur that never came. Early one morning, I heard an animal jumping across the stream behind me. I took a quick look back and saw a sleek cat slide down the opposite bank. I went down at noon and looked at the tracks left neatly in the sand but quickly went back up. It was a close encounter with a real wild animal capable of taking man down in a split second. As I was up in a tree, I assured myself I would be safe.

A collard tiger in the Western Forest Complex camera trapped on a forest road

After that, the urge to capture a tiger on film became an obsession and I finally decided to build my own camera-traps. I had the basic machining skills acquired after almost two decades of working as a rig mechanic in the oilfield, and before that the logging and heavy equipment industry. I have a small machine shop with a milling machine and assorted tools at home in Chiang Mai. I used a commercial camera-trap as the basis for my homemade ‘game or trail cameras’ as they are now called in the U.S. where a big business is flourishing..!

Tiger camera-trapped during the day by the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan

Tiger camera trapped along the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan My first camera-traps used passive infrared sensor boards purchased from ‘Radio Shack’ while I was back on vacation in the States. My close friend Yuthana Anantawala from Chiang Mai was working for Unocal in the Gulf of Thailand as an electrician, and he helped me wire up several ‘point & shoot’ film cameras to the electronic boards. I built the housings out of ‘TIG’ welded aluminum boxes and machined the case flat to incorporate a face-plate attached with machine screws for a tight seal.

Sealing and protecting the delicate electronics of the camera, board and batteries against moisture was the number one priority; silicon sealant forms a gasket to seal the case and is available everywhere, and silica gel (desiccant) in a small plastic bag to absorb any moisture was the trick. The first ones were simple and worked quite well. I tested them out the back of my shop where domestic and feral cats walked on a wall.

A feral cat walking the wall behind my shop testing a film camera-trap

In mid-2003, I set six camera-traps in Sai Yok along wildlife trails and waterholes. After four months, I finally got my first tiger, and then a second cat a few days later up on a 600-meter ridgeline. It was the beginning of a program to catch the striped cat on film. Other animals caught were elephant, sambar, barking deer, wild dogs, wild pigs, serow and stumped-tailed macaque. I even managed to catch a water monitor on one camera.

Notes from the field: My lucky number eleven.

When you play the dice game ‘craps’, the number eleven is a winner for money, but you loose the dice and the next throw. The following story is about my ‘number eleven’ – two very lucky photographs, but getting them almost cost me my life. It was November 2003 while working in Sai Yok. My team and I had just set a string of camera-traps deep in the interior of the protected area. As we were leaving camp, the cook asked me for a lucky number. I had just lifted my camp chair, which left an impression in the soft dirt like the number eleven, and so I shouted out to the boys that the lucky number was eleven.

A male tiger camera trapped with film in Sqai You National Park, Western Thailand

However, just after that, I became ill with the deadly Plasmodium falciparum (cerebral malaria) that almost killed me. The only thing that saved me was a medical procedure practiced here in Thailand for patients with severe malaria called a ‘blood exchange transfusion’. I stayed in the hospital for nine days and it was a slow recovery. I was lucky to survive. I will write a thread about that ordeal one day for Camtrapper and all the dangers of working in a Thai forest.

Some may argue that it was just a coincidence that 11 was recorded on both shots, but I like to believe the ‘spirits of the forest’ had finally answered my prayers. Ever since then, my luck has been a great roller-coaster ride in the exciting field of wildlife photography, publishing three coffee table books in English and Thai. Wild Rivers, my third book project, is just a continuation of a dream I had in Sai Yok more than 20 years ago, but that is another story.

A male tiger camera trapped on an old logging road in Kaeng Krachan

In 2004, I moved further south to Kaeng Krachan National Park in Phetchaburi province, Southwest Thailand and began a new program with some generous financial support from World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF-Thailand) and in cooperation with the Department of National Parks (DNP). A presence/absence program was initiated at two areas in the park.

The same tiger as above walking towards the camera

Within a few months, I managed to catch a big male tiger and several leopards on an old logging road about 10 kilometers from the main gate. The other area was along the Phetchaburi River deep in the interior.

The same tiger as above taking a real close-up

Over a period of three years, both cat species were caught on film in Kaeng Krachan consistently. The felines were in abundance. Leopards in both black and yellow phase were captured. The tiger and leopard have overlapping territories and hunt during the day and night.

Tiger named ‘4-spots’ camera-trapped in many areas of Kaeng Krachan

One tiger named ‘4-spots’ was consistently trapped in many areas of the park. I also managed to photograph a fishing cat, a rare occurrence. Other animals trapped were elephant, gaur, sambar, Fea’s muntjac, common muntjac, sun bear, banded linsang and striped palm civet among others like Indian civet, porcupine and fish-owl.

A first record of a tiger in a mineral deposit in Kaeng Krachan

It was a tremendous experience seeing all these exotic animals thriving in their natural habitat, and I looked forward to scrutinizing every roll of film. But it must be mentioned that there were many failures with equipment and even theft. I lost four cameras in Kaeng Krachan to poachers that probably had their photo taken and scared them. They actually bashed them until they busted open and chopped one out of a banyan type tree root. I dropped the program, as it was a very expensive loss including the cameras, gas, food and labor, plus whatever photos were lost. I do plan on returning to the Phetchaburi River one day but with much more robust camera housings hopefully to prevent further loss.

A male tiger with a collar camera trapped at night on a forest road in the Western Forest Complex

I then moved to Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Western Forest Complex-Thailand hoping to put my traps to work in a more tightly protected area. It did not take long to capture tiger and leopard, plus gaur, banteng, tapir, elephant, and many other creatures living in this World Heritage Site. And, I have finally lost two cameras to theft. From time to time, I still set traps in the sanctuary always hoping for a magical sighting of the big cats and other wonderful animals found here.

The same tiger as above but with a Sony DSLR camera on another date

Finally, the ‘digital camera-trap’ age has arrived. In November 2008 armed with a new digital camera-trap, a tiger (above) was caught in a salt lick not far from the main gate in Kaeng Krachan. It was an early morning shot of a mature cat and the first record of a tiger in a mineral deposit in the park. Prior to that, it was always thought the predator hunted around the peripheral of mineral licks that attracted the herbivores.

A young male tiger crossing over ‘tiger log’ in the Western Forest Complex

Kaeng Krachan and Kui Buri national parks have Thailand’s second best population of tigers and leopards, and both remain some of the top protected areas where they still survive and breed. I have left the Southwest are of Thailand and moved up to the Western Forest Complex.

There are three companies in the United States that specialize in passive infrared boards, and one company that offers active infrared controllers. I have listed web-address at the end of this thread in the event someone has a hankering to build a homemade camera-trap. The websites are very informative but it does require some extensive searching to get good information. Instructive data on modifying cameras and building your own camera-trap is listed.

A young female tiger with a collar crossing over ‘tiger log’

It is not easy anymore finding the right secondhand point-n-shoots like Sony, Nikon, Olympus or Pentax digital models at used camera shops or pawnshops anymore. They do float in and out of one place at the very end of Chinatown’s Yawalat Road on the right hand side of the road that sells second hand camera and video stuff. Make sure you thoroughly check the camera out, and even then, it might turn into a dud. The most popular camera for trail units is the Sony S600 digital with a 6-megapixel sensor and a Carl Zeiss lens. They take very good daytime photos and fair pictures at night.

A tiger camera trapped and squinting due to the camera flashes (2nd shot)

There is of course no warranty after a camera has been ‘hacked’; the terminology used for a camera wired up to a sensor board. And finally, many cameras do not work; only a few models listed by the board manufactures do. It takes skilled electrician lots of intricate work to get these boards and cameras working properly. I have spent loads of time and money on building camera-traps, but also have collected a large library of images of some very interesting, elusive and endangered animals to compensate the cost.

Notes from the field: “A tiger through the lens, and my lucky number 11”

A male tiger walking into a waterhole in the Western Forest Complex on Dec. 11, 2009

The same tiger taking a quick drink from the seep that is visited by many mammals

Good things sometimes come our way and I was about to get a reward to coincide with ‘2010 – The Year of the Tiger’. The absolute chronology of being at the right place, the right time with the right equipment and the right technique was played out before my eyes. On the 11th of December 2009 (my lucky number again), the tiger in the lead photo and I crossed paths.

Taking a quick look back at me in the photo-blind

The trail through dry dipterocarp forest takes about 45 minutes to walk to a photographic blind set above a waterhole deep in the interior of Huai Kha Khaeng. The flimsy structure made of bamboo sits about two meters off the ground and is attached to a tree. Black mesh closes off the cubicle on all four sides that was erected by the park rangers. An opening large enough for a big lens allows a clear view of the waterhole some 30 meters downhill to a saucer shaped depression.

This water supply attracts many creatures such as elephant, gaur, banteng and other ungulates like sambar and wild pig, especially during the dry season. Tiger, leopard and Asian wild dog also come looking for prey. It is truly a magical place and a tribute to Thailand’s natural biodiversity. Arriving about 12pm, I immediately set-up my cameras and then waited. Feeling dozy about 2pm, I strung my hammock for a bit of a snooze after the long haul from Bangkok. The afternoon passed-by and about 5pm I got up and began a vigil of the mineral lick.

the same tiger as above on the move.

A few minutes later I decided to actually sit behind my Nikon 400mm f 2.8 lens and D700 camera, and do some adjustments to compensate for the fading light. Took a few test shots to make sure the exposure was correct and then waited. Two minutes later, the dream of a lifetime unfolded before me. A striped carnivore magically and silently appeared from the forest on my right. The tiger walked straight down to a little stream for a quick drink. The mature male did not linger and continued on his way. However, he did pause briefly to stare up at my position three different times before disappearing into the forest on my left. Total time spent by the cat at the waterhole was less than a minute. He then circled my position and growled at me from where he had entered the waterhole; now that was exciting..!

A last look; he then circled my position and growled at me as a warning

I was lucky to have been sitting down with my hands on my lap in front of my camera. If I had been standing, or made just the slightest noise, I would have never seen this old male. I was extremely fortunate to snap 20 frames as this magnificent creature carried on its way. I banged my head against my camera in disbelief to make sure I was not dreaming. The ultimate photograph for me was now in the bag so to speak.

Notes from the field: Camera equipment and technical elements

In order to photograph these elusive predators or any other large mammals or birds for that matter, a large lens (400mm to 600mm) and a semi-pro to pro camera body from any of the big guns like Nikon, Canon, Pentax, Olympus, Sigma and Leica is needed. A tripod and a shutter release is an absolute must for sharp shots. It must be understood though that this equipment is expensive.

I set my Nikon camera to aperture priority (auto), an appropriate ISO depending on the time of day or the light (normally 400 ISO), and the white balance to ‘cloudy’ with an f-stop of ƒ5.6 to ƒ8 with minus -7 compensation. This gives me a good starting point and I can quickly change these settings or compensation for the ever-changing light in the forest.

After 20 years of wildlife photography, my aspiration to photograph a tiger through the lens has finally come true. However, in closing and it does need repeating; the powers to be (the government) must come up with much better management plans for saving not only the tiger but all the rest of wild animals and ecosystems that evolved over millions of years. It is hoped my photographs of the tiger and other amazing Thai animals will create conservation awareness, so that the destructive process of modernization and humanization can be slowed if not stopped. The Kingdom’s natural resources are irreplaceable and time is running out!

Camera-trap units and equipment manufacturers:

The following companies specialize in camera-trap electronic infrared boards plus equipment, complete units and knowhow (listed below). I recommend these as the best but there is a rip-off or two with loads of empty promises, lots of jargon and does not deliver on their promises, so beware. Due to possible litigation, I am not at liberty to say who they are so please do not ask. When you see a lot of rambling on about how good they are, think before buying. I know because they burned me with boards that did not work and then would not be responsible for the poor quality and/or replacements. There are also complete camera-trap units available from quite a few manufacturers but are quite expensive for the good ones. The cheap ones do not stand up to the tough conditions of most Thai forests. Importing them into Thailand can also be costly with shipping and taxes. The main reason why I build my own.

Passive infrared boards:

http://www.snapshotsniper.com and http://www.rcdavisgamecamerasolutions.weebly.com/

Completed camera-trap units are also available: For an in depth overview on trail cameras check out ‘Trailcampro.com’

Moultrie.com – Cuddleback.com – Bushnell.com – Browning. com – Reconyx.com (the quickest trail camera on the market) are just some of the makes and many others via for market share.

Some final words: If you live near a forest in Thailand or anywhere in the world, chances are there might be some cryptic wild species still living there. But unfortunately, domestic plus feral dogs and cats can be found in many of these small patches of wilderness, and take everything they can catch and eat. I once camera-trapped feral dogs at 2,300 meters above seal level in Doi Inthanon National Park in Chiang Mai, Northern Thailand. It was a very disappointing discovery, and I only felt remorse for all the beautiful creatures struggling to live in this high-montane forest.

The frustrations, expenses and difficulty of photographing wildlife vanish when I view my work, and that keeps me going after those elusive tigers and other cryptic species. I have had some great success camera-trapping tapir, clouded leopard and marbled cat (poor night-time photo but good record shot) down south in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary. This location is very deep in the protected area and I plan to do some serious work here to catch this beautiful marked predators and mammals, as they are very endangered and difficult to observe in the forest.

As most of you know, I have been working with more sophisticated camera-traps using DSLR digital cameras with good lenses and multiple flashes for improved photo quality. I have posted many threads and photos concerning this new camera-trap work. It is truly an exciting experience when one sees digital files with wild animals going about their daily lives as nature intended. It makes everything worthwhile….!

A Black Leopard in Broad Daylight

A rare encounter: A black cat appears deep in the interior of the Western Forest Complex

My first black leopard in the late afternoon sun showing its spots some 15 years ago.

It is late April in the forests of the Western Forest Complex, one of my favorite places in Thailand. The first rains have come and doused the dangerous forest fires that spread throughout the area during the dry hot season starting in March and ending in May.

As usual, I’m setting-up camera traps at a hot-springs (mineral deposit) not far from a ranger station some 50 kilometers deep in the interior accessible only by a dirt road.

This natural seep is visited by all the large mammals including tiger, leopard, elephants, gaur, banteng, tapir, sambar and many other smaller creatures, and provides excellent opportunities for some great animal shots.

As I was going through a few of my camera traps changing out cards and batteries, I decided to have a quick look at a 2GB card that was in one of my cams.

A black leopard in mid-afternoon camera trapped on a trail to the hotspring.

Imagine my surprise to see a shot of a ‘black leopard’ in mid-afternoon walking up a trail shown in the story. Other denizens caught in this series include elephant, tapir, sambar, wild pig and muntjac (barking deer) over a month period back in February of this year. The leopard was truly a bonus and I had actually closed out the program with this cam.

This black leopard brought back fond memories of this place more than 15 years ago. I was sitting in a tree blind up by the hot springs when a black leopard walked out into the open about 4pm and posed for me at several places for over the next hour.

Those were in the old days of slide film, and I did not know how good the shots were until the film was processed. A few images are shown here from that lucky sequence many years ago. The sun was low and the black leopard showing its spots is one of my best wildlife photographs ever.

Posing on a fallen tree at the beginning of my career of wildlife photography.

Sometimes things happen in succession that boggles the mind. On May 6th, I posted the ‘black leopard’ camera trap image on my website. The next day I left Bangkok very early in the morning and arrived at the hot springs. I was back to reset camera traps, and this time to sit at the base of the old tree for some through-the-lens work. Who knows what might show-up.

Resting in the late afternoon and scoping out the area for prey, May 2013.

This black cat stayed for about 10 minutes.

A rare carnivore still surviving in Thailand.

Another once in a lifetime encounter as it leaves the mineral deposit.

I was with my good friend Sarawut Sawkhamkhet, a Thai wildlife photographer. We arrived and set-up a temporary blind about 3pm. The weather was warm and balmy with nice clear-blue skies.

At 5:45pm, the unthinkable happened! A ‘black leopard’ appeared out of the forest near the springs and walked over for a drink, and then disappeared for a short while. Then this magnificent creature came back and flopped down on all fours twitching its tail looking straight at us and staying for about 10 minutes before going back in the forest where it had come from.

The leopard (Panthera pardus) described by Linnaeus in 1758 is the second largest cat in Thailand. Once upon a time, leopards could be found in most forests of the Kingdom. These felines are still surviving quite well in protected areas in the West, and many forests in the South. The central, eastern and northeastern regions have no reports of leopard for long time now.

Pound for pound, the leopard can take on some seriously large animals several times its size. The leopard is closely related to the jaguar of South America. Both have a spotted coat pattern and incidence of ‘melanism’ or black phase. Many people have a misconception about the black leopard (also known as the black panther) as a separate species but in fact, it is the same as the yellow phased leopard.

The present distribution of the leopard is restricted to Asia Minor, India, Southeast Asia, the Himalayas, Tibet, China, Siberia, and Africa. Fossils of leopards have been found in Pleistocene deposits throughout Europe, the Middle East, Java, and Africa, some 1.5 million years old, indicating the leopard arrived after the tiger which has been around for about two million years.

These secretive cats are mainly nocturnal but in some localities, they are active in the day too. Their populations and ranges are difficult to determine but radio tracking of collared animals has shed new light on their movements and areas they live in.

Sighting a leopard in Asia is extremely difficult, and even catching a rare glimpse of this very essential top predator is tough due to its solitary and stealthy behavior. However, luck can sometimes play an important part in viewing the leopard and I feel lucky to have seen and photographed them on quite a few occasions.

My most thrilling or heart stopping adventure with a black leopard happened in Huai Kha Khaeng about five years ago while I was sitting up on a bluff overlooking the river. A photographic blind was erected on the rock-face about 20 meters up with a small trail that enabled me to get into the hide. The sun was bright and the weather was warm during the dry season.

About 9am, several monks down by the river passed on but did not see the camouflaged structure as they went their way. After that, I came down for lunch and set some camera traps at a mineral deposit nearby. At 2pm, I settled back in the blind and began a vigil of the river. I started to feel a bit groggy as the sun was beating down on my position. I moved my camera in to save it from the direct sunlight.

All of a sudden, I was startled by a guttural growl outside the enclosure. I stood up peering out the window and came face to face with a huge round black head and yellow eyes about two meters away that penetrated my soul. My first instinct reaction; it was a big black dog. But that quickly changed as the creature stared intently at me before bounding down the trail it had come up. The big cat was gone in a split second. Of course there was not enough time to get any photographs. The incident surely is etched in my memory.

Without doubt, the future of the leopard depends on one thing only – the complete protection of the remaining forests where they live. If the national parks and wildlife sanctuaries remain intact with a high number of prey species, the big cats will survive. But if over-development, poaching and encroachment are allowed to continue, the large cats will eventually disappear.

Unfortunately, too much time and money is wasted by too many organizations talking about saving wildlife and their habitats, with very little actually being done. Human population growth will eventually destroy most wild places. Only true protection by some dedicated people will slow the destruction of nature’s precious wildlife and wilderness areas. It is hoped the leopard, and the tiger, will continue to survive as they have for millions of years.

The Siamese Crocodile – Update 2011

Critically endangered crocodilian species

Thailand’s last few remaining wild crocodiles

Two hundred and thirty million years ago, the first crocodilians evolved from archosaurs or ‘ruling reptiles’ during the mid-Triassic period of the Mesozoic era when primitive dinosaurs also roamed the planet. Crocodiles have changed little in body structure since then. Apart from birds, these reptiles are the only living archosaurs.

My first Siamese crocodile in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

“Note forest fly on the eye node; these insects take saline from the croc’s eyes”

In 1909, J.B. Hatcher discovered a few fossilized bits and pieces of a giant alligator in Montana from the late Cretaceous period 80 million years ago. Deinosuchus was also found in Texas by Barnum Brown of the American Museum of Natural History in New York in the 1940s. The skull of this huge crocodilian is two meters long and body length estimated at about 12 meters with a weight of 8.5 tons.

Sarcosuchus was another crocodile some 12 meters long and weighing up to 10 tons. Fossils were first found in Central Africa from the early Cretaceous 112 million years ago by French paleontologist Albert-Felix de Lapparent in 1964, and then by France de Broin and Phillip Taquet in 1966. Later in 1997, Paul Sereno discovered more fossils in the sub-Sahara desert and then tagged the beast as ‘Super-Croc’.

This huge crocodilian was also unearthed in Brazil by a British geologist, and described by Eric Buffetaut and P. Taquet in 1977 as the same species found in Africa. These ‘super-crocs’ pulled dinosaurs and other large animals into the water and devoured them.

The same crocodile camera trapped in Khao Ang Rue Nai

In 1979, Nares Sattayarak, a geologist for the Department of Mineral Resources working in the northeast province of Nong Bua Lamphu discovered the lower jaw of a huge crocodile in a road-cut excavated from the Phu Kradung Formation of the late Jurrasic 150 million years ago. Named Sunosuchus thailandicus, it was described as a new species by Eric Buffetaut and Rucha Ingavat. Estimated to have been at least eight meters in length with a lower jaw over a meter long, it was Thailand’s ‘super-croc’.

Then in 2005 a fossil several million years old of a ‘gavial’, a large fish-eating crocodilian was unearthed by Dr Yaowalak Chaimanee and her team from the Department of Mineral Resources. This discovery was made on the Khorat Plateau at Ban Khok Sung in Nakhon Ratchasima province. The species still exists in Burma and India.

Sometime in 2006, Komsorn Lauprasert, a scientist at Mahasarakham University discovered another species of crocodilian 100 million years old that had longer legs than modern-day crocodiles and probably fed on fish, based on the characteristics of its teeth.

My second Siamese crocodile in Kaeng Krachan National park

According to Komsorn, “They were living on land and could run very fast”. The 15cm. long fossil-skull was originally retrieved from an excavation site in Nakhon Rathchasima province and then found in a museum. The species has been named Khoratosuchus jintasakuli after the province and the last name of the director of the Northeastern Research Institute of Petrified Wood and Mineral Resources, Pratueng Jintasakul.

Some 50 years ago, Thailand had three species of wild crocodiles found in a host of environments: the sea, estuaries, rivers and marshes. The most common species was the Siamese crocodile (Crocodylus siamensis) and was considered a pest by village folk who lived near waterways that had the reptiles.

Another thin-snouted freshwater crocodile was (Tomistoma schlegelii), also known as the ‘false gharial’ found only in rivers of the southern peninsula.

Crocodile river in Khao Ang Rue Nai

The estuarine ‘saltwater’ crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) today is the largest in the world also known as the ‘Indo-Pacific’ crocodile. The species was very common in river estuaries and islands in the Andaman Sea and the Gulf of Thailand. Huge saltwater crocs have been sighted swimming in open-ocean.

Unfortunately, both the saltwater and false gharial has disappeared from the wild of Thailand, and the Siamese is technically extinct with only two individuals left; one in the East and one in the West of the Kingdom. This is truly a sad state of affairs concerning the crocodile after having outlived the dinosaurs for more than 65 million years.

The Siamese crocodile was once very common in Southeast Asia including Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Laos and possibly Burma. Populations throughout the region have seriously declined and exact numbers of wild crocs are not known in any of the range countries.

Wild Siamese crocodile in southern Cambodia

There is a small population still thriving in Cambodia. However, their habitats are under serious threat from hydroelectric dam construction and could be wiped out very soon.

Conservationists from ‘Flora and Fauna International’ and ‘Wildlife Alliance’ are capturing wild Siamese crocodiles and plan to use these to launch a conservation breeding-program in partnership with the Cambodian Forestry Administration. My close friend and English wildlife photographer Allan Michaud has photographed a Siamese crocodile in southern Cambodia.

Crocodilians for most of their 230-million-year history have been large, long-bodied, aquatic carnivores. Armor plating (in the form of bony scutes set in their hides), extended tails, short strong limbs, and powerful sharp-toothed jaws make them formidable predators.

Crocodile tracks by the Phetchaburi River

Crocodiles come onto land to defecate and, being cold-blooded, to bask in the sun to regulate their body temperature. Female crocs come ashore to lay 20 to 40 eggs in mound nests on land near the water’s edge. These streamlined submarine predators glide through water with ease, surfacing and submerging at will.

Siamese crocs grow broad and heavy, and mature individuals have distinct bony ridges behind the eye socket. Historical records report specimens of up to four meters in length but three meters is the average for a mature adult. They feed primarily on fish but also take frogs, small mammals and birds. Undulating their powerful tails while tucking in their legs, crocs can glide through water without making a ripple.

Stealthily stalking prey along the water’s edge, they can snatch in an instant with powerful jaws pulling it below to drown their victim. Some crocs lay in wait on the bottom of a river or pond in order to grab fish and can stay underwater for an extended period of time.

Crocodile pond in the Phetchaburi River

If the carcass is too large to swallow whole, they stash it under water until ripe and then tear it apart. Adults can survive for many months without a meal and thus are one of nature’s most efficient predators in terms of consumption proportionate to body size.

Man is the crocodile’s only enemy, and the wild Siamese crocodile is probably the most endangered crocodilian species in the world wiped out by man’s greed.

At the end of World War II, crocodile farming came into vogue in the Kingdom, and wild crocs were captured for breeding stock. Thousands upon thousands were caught in the booming trade. Habitat loss and crocodile farming started the countdown to extinction for these ancient creatures. With no laws to protect them, crocs were eradicated from every river and swamp in the country.

River carp at the crocodile pond in the Phetcahburi River

Farming crocodiles is big money business in Thailand. The false gharial and saltwater crocs are farmed along with the Siamese. A quick growing crocodile has been produced by crossbreeding the Siamese with the ‘saltwater’ species producing a ‘hybrid’ found in most of the farms throughout the country. This human ‘quick-growing’ creation is farmed for its meat and hide, and continues to be a brisk business.

The recent floods in the Central Plains have allowed hundreds of legally and illegally farmed crocodiles to escape into the environment. Many have been shot, some captured and some are still on the loose. The danger to humans is probably nil. However, farmed crocs are much more aggressive than wild ones and if one is sighted, the authorities should be notified immediately.

During my career as a wildlife photographer, I have had the great fortune to photograph two crocodiles in the wild: the first one in 2001 at Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary in the East, and in 2003, the second one in the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan National Park in the Southwest. I also camera trapped the first one in 2002 shown in the lead photograph.

Siamese crocodile in the Samut Prakan Crocodile Farm

One thing has been determined about these two creatures: The old croc in Khao Ang Rue Nai is probably a male (no egg nests have ever been found here), while the mature individual in Kaeng Krachan is more likely a female as many nests have been found up-and-down the river over the years but the eggs are never fertile. Female crocs lay eggs regardless of fertilization by a male or not. The possibility of bringing the two together to mate is absolutely zero.

Some old reports suggest that Siamese crocodiles could still exist in the northeast in several other protected areas: Pang Sida National Park (Sa Kaeo province), Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary (Chaiyaphum province) and Yot Dom Wildlife Sanctuary (Ubon Ratchathani province) but with no actual records, it is doubtful if they still survive in these locations.

My good friend Kitti Kreetiyutanont of the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department (DNP) wrote a paper on Siamese croc sightings in 1993 and, indeed, photographed one at Khao Ang Rue Nai. It is thought to be the same animal I photographed. In 2003, poachers in Yot Dom near the border with Cambodia killed a female crocodile with eggs, and its skull and skin are on display at the park.

Siamese crocodile photographed in Khao Ang Rue Nai

The DNP and other organizations should support surveys to see if any other wild crocodiles still exist in Thailand. Restocking a few carefully selected sites with yearling purebred Siamese crocodiles seems to be the only solution.

But that raises questions about the suitability of the farmed crocs available for release. Have captive animals been excessively inbred? Even more critical, have they been crossbred with other species? Only good genetic DNA analysis can unravel this intricate problem of the species’ integrity in the farms.

In 2004, the DNP in conjunction with a local crocodile farm started a pilot project to reintroduce Siamese crocodiles at Pang Sida National Park. Seven juveniles were being kept in a holding pen for future release close to Pang Sida waterfall. However, it is reported that a few escaped and the farm abandoned the project.

Over the last few years, newspaper reports of crocodiles seen in Khao Yai and Thung Salang Luang national parks were probably released without the DNP’s knowledge, and more likely to create media frenzy by someone.

The croc in Khao Yai is aggressive as several tourists found out one day standing by the banks of the river where the croc is living. The reptile rushed up to the people probably looking for food. The chief then roped off the area by the waterway. Siamese crocodiles are very secretive and avoid people period, and are difficult to see in the wild. The department should capture this croc and remove it being alien to this place above Haew Suwat waterfall.

Serious efforts are required to save Thailand’s remaining wild crocodiles. No matter how many crocodiles are kept in farms, only an intact natural population can truly save these ancient creatures from total extinction.

Thailand should serve as a role model for wildlife conservation in Southeast Asia, and the Thai people and the government should join hands to save and protect the Siamese crocodile for present and future generations. Action needs to be undertaken now to ensure that a creature of 230-million year evolution continues to survive.

Thailand’s Primates: Terrestrial and arboreal mammals

Wild Primates: Gibbon, macaque, langur and loris

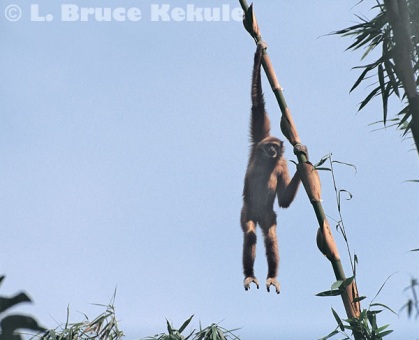

Gibbon hanging from bamboo in Kaeng Krachan National Park

During the Miocene Epoch (5.3-23.8 million years ago), a relative of the orangutan ape lived in the dense jungles in what is now north and northeast Thailand. Scientists digging in coalmines and sandpits have produced some very amazing fossils.

Other primates like a 13-million year old tarsier and an early Adaptiform primate have also been found in the Kingdom. The oldest anthropoid from the fossil record is Siamopithecus eocaenus, or known as ‘Siam Ape’, and found in 40 million year old strata in Krabi province down South. This legacy is just another part of Thailand’s remarkable natural heritage.

Pig-tailed macaque in Khao Yai National Park

In 2003, an extremely important discovery was made by paleontologist Dr Yaowalak Chaimanee of the Department of Mineral Resources in a lignite mine near Chiang Muan district in the northern province of Phayao. Fossilized teeth of a hominid primate about 10 to 13.5 million years old, was brought forth. The ape was first named Lufengpithecus chiangmuanensis and is related to orangutans. It has latterly been reclassified and renamed to Khoratpithecus chiangmuanensis all because of another amazing new discovery.

In 2004, a new species of fossil orangutan about 7-9 million years old was dramatically uncovered on the Khorat Plateau in Nakhon Ratchasima province. Thailand once again found itself on the world’s paleontological map. The new ape was named Khoratpithecus piriyai (ape from Khorat) after Piriya Vachajitpan, who played a major role in the discovery at the Tha Chang sandpits in Chalerm Phrakiat district. The lower jawbone and teeth have a U-shaped dental arcade similar to that of a living ape – and of human beings.

Crab-eating macaque in Sai Yok National Park

Modern orangutans hail from the Pleistocene era, from 2 million to 100,000 years ago. Their geographic distribution once included much of Southeast Asia. However, they became extinct from many areas because of deforestation and hunting. Today, the orangutan can only be found in Borneo and Sumatra.

The orangutan is the only great ape with a fossil record. Strangely, no African fossils have ever been found that are related to chimpanzees or gorillas. But determining the ancestry of the orangutan has still proven extremely difficult.

Dusky langur in Kaeng Krachan

Dr Yaowalak has also discovered other primates like Siamoadapis maemohensis, a primitive primate. A new species – named Tarsius sirindhornae (named after HRH Princess Sirindhon) – that lived about 13 million years ago has also been found. Tarsiers are primates that share a common ancestor with monkeys and humans.

Primates started evolving more than 50 million years ago during the Eocene when mammalian evolution accelerated. A newly found species small enough to fit in the palm of a hand is North America’s oldest known primate, according to a new study. Christopher Beard, a paleontologist at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, recently discovered fossils of the 55-million-year-old creature on the Gulf Coastal Plain of Mississippi.

Slow loris in Kaeng Krachan

Named Teilhardina magnoliana, the animal is related to similarly aged fossils from China, Europe and Wyoming’s Big Horn Basin and is the oldest primate ever discovered. They are very primitive relatives of living primates called tarsiers, which live today in Southeast Asia.

A new kind of primate that lived 43 million years ago has been discovered in the Big Bend region of West Texas. Named Mescalerolemur horneri, it was among the last primates endemic to North America. This petite creature, weighing just 370 grams, is related to modern-day lemurs found only in Madagascar.

Pileated gibbon male and female in Khao Ang Run Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

The Primate order includes tarsiers, lemurs, lorises, monkeys, gibbons, large apes and humans. Also known as simians, the sub-order Anthropoidea is comprised of apes and humans, and New and Old World monkeys.

Some scientists now believe that some hominoid primates evolved in Asia, possibly in parallel with Africa. A faunal dispersal corridor is believed to have existed between Southeast Asia and Africa during the Middle Miocene. Fossils of human species Homo erectus have been found both on the island of Java and in China. Many new hotly debated theories have erupted within scientific and academic circles.

Crab-eating macaque in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary

Wild primates in the Kingdom include slow loris and various macaques, langurs and gibbons. Most live in the forests of protected areas. Populations are dwindling, however, as forest habitat is slowly destroyed and unsurped by humans. The future of wild primates is on nature’s balancing beam. They only really survive in the top national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and reserved forests where there is little human influence and disturbance.

Undoubtedly, among the world’s most charismatic and vocal members of the rainforest are the gibbons. Their calls are inspirational, beautiful and scientifically fascinating. I once listened to three separate groups calling in mid-morning while trekking through Kaeng Krachan National Park. It was a beautiful moment in my travels through this forest.

Stump-tailed macaque mother and baby in Kaeng Krachan

Once while I was packing-up at the end of the road in the park to go down to the Phetchaburi River, an opportunity to catch a gibbon on film presented itself. This dark-blond white-handed gibbon all of a sudden swung out on a single bamboo and seemed like “here I am and hurry up” as seen in the lead photograph. I quickly got my camera and long lens and rested it on a sandbag at the back of my pick-up. After a few shots, it melted back into the forest. The blue skies, light and subject contrast is a wildlife photographer’s dream.

Four species of gibbon live in the Kingdom: white-handed gibbon, pileated gibbon, agile gibbon and siamang. A few hybrids have been identified where the white-handed and pileated gibbons overlap in forest habitat in Khao Yai National Park.

Dusky langur eating leaves in Kaeng Krachan

If a forest has substantial gibbon populations, it usually means the wilderness is fairly intact. But some suitable forests are becoming as rare as the animals themselves due to the deadly tandem of encroachment and poaching spreading throughout the wild primate range.

Gibbons spend their entire life in the trees. Their whooping calls can be heard over long distances and can erupt at any time during the day or night. Gibbons may start calling at 4:00am in some forests and they usually quiet down after midmorning, although they will sometimes vocalize in the afternoon. Gibbons are very active as the sun rises moving to fruiting trees. The white-handed gibbon, the most common species, is found throughout most of the country while the pileated gibbon survives only in the east. The agile gibbon and siamang live in a small pocket near the Malaysian border.

Dusky langur sitting on a stump in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

There are four species of langur: Phayre’s, banded, silvered and dusky or ‘spectacled’. Known also as ‘leaf monkeys’, they share the same predicament as gibbons. Langurs have slender bodies and limbs, with a tail longer than the head and torso and the species differ in coloring: black, gray, dark brown to reddish with some albino. These monkeys are eagerly hunted for their meat, blood, and for gallstones, which are valued in Chinese medicine. These nimble acrobats live in trees but descend to the ground to eat fallen fruit, drink water and take in minerals. They are one of the most sought after primates.

Five species of macaque are found in Thailand: Assamese, rhesus, stump-tailed, pig-tailed and crab-eating, also known as long-tailed. Macaques are the most common wild primates and some species live near or even within cities, usually associated with Buddhist temples where they have become habituated. Some species live in steep limestone hills and cliffs near human settlements. Pig-tailed macaques beg for food from passing motorists on the road close to the headquarters at Khao Yai. Some people who feed these creatures often receive serious bites, as these monkeys can be vicious.

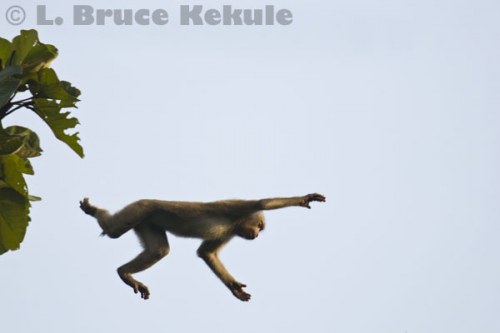

Leaping langur in Kaeng Krachan

Stump-tailed macaques are probably the fiercest of the five species, living mostly in deep forest far from humans. Males have huge fangs and can inflict terrible wounds. These monkeys are terrestrial creatures foraging for food on the ground. They rarely climb trees, although have been seen in the forest canopy, most often when fleeing poachers and gunfire. Now rare in the wild, stump-tailed macaques are found in a few protected areas.

Slow loris is the smallest of Thailand’s wild primate species. Nocturnal and arboreal, they live in the trees of primary and secondary forest, and also groves of bamboo. These cuddly balls of fur are seldom found on the ground and are renowned for their deliberate, slow hand-over-hand movement while traversing a tree branch. Slow loris can be seen at night on fruiting trees in some of the top protected areas.

Stump-tailed macaque by the Phetchaburi River

Sadly, all these primates are eagerly sought after for the illegal pet trade or Asian medicine trade, and trade in baby gibbons taken from their mothers are an ongoing threat. Macaques are used in the coconut trade (the monkeys are sent up a tree to collect the nuts, usually for a food reward) and some are abused.

Dr Warren Brockelman is widely known as one of Thailand’s top scientists studying primates especially the gibbons in Khao Yai National Park. He established a study plot to monitor the gibbon’s feeding habits and ranging behavior. Other studies included plant-animal interactions and forest community dynamics on the 30-ha ‘Mo Singto’ forest dynamics plot in Khao Yai.

Pig-tailed macaque jumping in Khlong Naka Wildlife Sanctuary

Primatologist Dr Suchinda Malaivijitnond with the Primate Research Unit at the Department of Biology, Faculty of Science in Chulalongkorn University has done a lot of research on primates specializing on the long-tailed (crab-eating) macaques.

Her work in 2005 included surveys of long-tailed macaques at Piak Nam Yai Island, Laem Son National Park in Ranong Province, situated in southern Thailand. Long-tailed macaques found on the island were observed using axe-shaped stones to crack rock oysters and swimming crabs. They smashed the shells with stones that were held in either the left or right hand, while using the opposite hand to gather the meat.

Pig-tailed macaque stealing food in Khao Yai

I have mentioned many times in my stories in the past that the most important issue pertaining to the protected areas is protection and enforcement. If the forests and wildlife are looked after, they will continue to thrive. If poaching and encroachment is allowed to carry on, the Kingdom’s natural ecosystems will decline.

Positive and swift action is the only option for the Thai government in taking care of the natural resources. Better management, up-dated laws and increased funding are most imperative. Only then can the future for all of Thailand’s wild living things be definite.

Crab-eating macaque eating a bag of dry noodles

Hornbills: Indicator species of an intact ecosystem

WILD SPECIES REPORT

Majestic birds and living fossils

Wreathed hornbill in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Most people are familiar with the hornbill, nature’s amazing avian fauna with large bills and a casque, and some with raucous calls. They also have strange but interesting nesting habits and the larger hornbills make a loud whooshing noise when flying sounding much like a locomotive, and heard from quite a distance. In any given forest, if they thrive it means the ecosystem is fairly intact.

Brown hornbill at a ground nest hole in Huai Kha Khaeng

The hornbill belongs to an ancient family (Bucerotidae) of birds seen in fossils from the strata of the ‘Eocene’ period of Europe some 50 million years ago. Through tectonic-plate movement, hornbills however have become restricted to tropical Africa and Asia, and there are 55 species found in the world with 24 in Africa and the rest surviving in the forests of South and Southeast Asia. Thailand has twelve species recorded throughout the country, and all still thrive but some are endangered.

Wreathed hornbill with fruit for his mate in the nest

These noisy, social, omnivorous birds need large tropical forest areas with many fruiting trees throughout the year to survive. Giant emergent trees with nesting cavities are also important to carry on their legacy but some species nest near the ground. The diet of the hornbill is a preponderance of figs and other fruits but also take animal food such as snakes, lizards and small bird hatchling needed for dietary protein when rearing the chicks.

About six years ago, my dream to photograph hornbills at a nest became a reality. The month is May and I’m sitting in a hot, humid blind in the dry evergreen forest of Kaeng Krachan National Park. The location is near the 9th tier of Thor Thip waterfall about 10 kilometers from Phanern Thung ranger station in the interior of the protected area.

Great hornbills flying off a fig tree

A pair of wreathed hornbills was sighted coming and going from a nest-hole by a forest tour guide, and relayed to my close friend Suthad Sappu who has been a ranger with the park for more than 15 years, who informed me and I made immediate plans to make a visit. It took me a few days to get going and I finally loaded up my old 4X4 pickup truck making my way out of Bangkok to Phetchaburi province in southwest Thailand, a three-hour ride.

We eventually arrived at the end of the road at Kilometer 36 and immediately got ready for the 4-plus kilometer walk downhill to the waterfall along a well-established nature trail. On a hill across from a tall tree with a large hole in it, I quickly set-up a blind and went into hiding.

Rufous-necked hornbill in Mae Wong National Park

A pair of wreathed hornbills chose this cavity for their nest. By the time I got there, the female was already inside and the front had been closed-in with droppings. This chore is taken care of by the female so that just a small slit is left. The perch above the hole is just right to allow the male to feed the occupants with fruit and small animal morsels.

In a short while, a loud whooshing noise was heard and the male hornbill arrived as the morning light glowed. The large bird popped out fruit and gingerly fed the female. It was a beautiful experience seeing and photographing this great natural spectacle. After filling my card with digital images, I waited until the bird left on another fruit gathering mission and then left quietly. As always, this sighting is etched in the old memory bank.

Wrinkled hornbill in Hala-Bala Wildlife Sanctuary

The chicks eventually hatched and the cycle of life began for yet another group of hornbills. The female finally emerged and left the young ones in the nest for a while longer as the adults continued to feed them. One day, they eventually outgrew the nest and broke free. It is one of the greatest success stories of the natural world.

Hornbills unfortunately have been persecuted for their large bill and casque as an ornament. Poachers for subsidence also eat these large birds. This has greatly impacted all species of hornbill throughout the Kingdom but there are still many protected areas where they can be found. Many are near extinction at the hands of man in his quest to survive with the destructive forces of encroachment and poaching.

White-crowned hornbill in Hala-Bala

In 1996, Japanese photographer Atsuso Tsuji published an excellent book in conjunction with Sarakadee Press entitled ‘Hornbills – Masters of Tropical Forests’ about these amazing creatures. This tome is now out of print but probably can be found in some used bookstores. With many photographs and text, he delves into the lives of hornbills in Khao Yai National Park. There are chapters on nesting, roosting and feeding habits, and in particular the entire life cycle of hornbills.

A story about hornbills in Thailand would not be complete without mentioning biologist Dr Pilai Poonswad with Mahidol University who has dedicated her life to the study and research of this magnificent avian fauna, and she has also published a scientific journal concerning the subject. Her work has included helping hornbills to choose nest holes by installing a ledge just below the cavity to allow these large birds to perch easily while feeding the female and chicks inside.

Great hornbill in Khao Yai National Park

I was very fortunate to photograph a great hornbill male in Khao Yai while it visited a nest very close to the main road in the park shown in the story. Ajarn Pilai and her team has also worked in other protected areas like Huai Kha Khaeng, Hala Bala and Khlong Saeng wildlife sanctuaries, and Keang Krachan and Khao Sok national parks plus many others throughout Thailand to monitor these birds, and she has established the Hornbill Research Foundation to further the study and protection of these majestic animals.

Down south in Surat Thani in the rich forests of Khlong Saeng next to Khao Sok, I did a camera trap survey deep in the interior catching many animals including a white-crowned hornbill down on the ground next to a large waterhole shown in the story. I also photographed a brown hornbill at a nest hole on the ground in Huai Kha Khaeng.

Oriental pied hornbills in Kaeng Krachan

My close friend Sarawut Sawkhamkhet photographed a pair of Oriental pied hornbills at a waterhole in Kaeng Krachan. Another fellow wildlife photographer Saman Khunkwamdee photographed helmeted and rhinoceros hornbills many years ago down in Hala-Bala Wildlife Sanctuary during peacetime in Southern Thailand on the border with Malaysia. Another close friend Vanchai …….a has photographed all 12 species, quite a feat and just recently visited Hala-Bala capturing the very rare wrinkled hornbill and others in the sensitive south.

The future of the hornbill in Thailand is the same for all species that inhibit pristine forests; they must be protected at all costs from destruction by encroachment and poaching. This responsibility rests with the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation, and it is imperative that the management, protection and enforcement is greatly improved so that the magnificent protected areas remain intact. The government and private sector should work together to insure hornbills and all the other creatures and ecosystems remain part of Thailand’s amazing natural heritage.

Oriental pied hornbill with fruit for its mate

According to the very informative ‘Birds of Thailand’ by Boonsong and Round, there are 12 species of hornbill found in Thailand as follows:

1) White-crowned hornbill (Berenicornis comatus) with a bushy white crest and blackish bill and a small casque. Habitat is evergreen forests from foothills to 1000 meters, and is an uncommon resident.

2) Brown hornbill (Plilolaemus tickelli) is relatively small in size and brown plumage with white orbital skin and yellowish bill and small casque. Found occasionally in mixed deciduous forest adjacent to evergreen forest up to 1,500 meters. They are an uncommon resident.

3) Bushy-crested hornbill (Anorrhinus galeritus) has mainly black plumage with a small casque and a thick, drooping crest and pale blueish gular and orbital skin. Found in evergreen forest from the plains to 1,000 meter. They are fairly common resident.

4) Rufous-necked hornbill (Aceros nipalensis) is identified by a combination of bright blue orbital skin and bright orange-red gular pouch, and yellowish ivory bill with no casque. Found in evergreen and hill evergreen from 600 meters to 1,800 meters, and is a rare resident.

5) Wrinkled hornbill (Rhyticeros corrugatus) has all black wings and is distinguished from wreathed hornbill by smaller size. Yellowish bill and small reddish casque. White gular pouch in males and blue gular pouch in males. Found in lowland evergreen forest in the South. Rare with just a few left in Southern Thailand due to habitat destruction.

6) Wreathed hornbill (Rhyticeros undulates) shows all black wings with a white tail, and black bar on gular pouch that is yellow in males and blue in females. Diagnostic corrugations on sides of both upper and lower mandibles. Found in evergreen and mixed deciduous forests from the plains to 1,800 meters. They are an uncommon to locally common resident.

7) Plain-pouched hornbill (Rhyticeros subruficollis) in coloring is similar to the wreathed hornbill but distinguished by slightly smaller size. Lacks corrugations on sides of bill. Found in evergreen and mixed deciduous forests of the lowland and lower hills. They are a rare resident.

8) Black hornbill (Anthracoceros malayanus) is small in size with all black plumage with white tips on tail feathers. The bill is yellowish white in the male and blackish on the female and both with a whitish cassque in both sexes. They are found in evergreen forests in the plains and foothills, and are a rare resident.

9) Oriental pied hornbill (Anthracoceros albirostris) is identified by its small size, whitish face patches, white lower breast and belly. The bill and casque is ivory-colored and marked with black with casque larger in males but more heavily marked blackish in females. Can be found in evergreen and mixed deciduous forests and secondary growth from the plains up to 1,400 meters, and is a fairly common resident.

10) Rhinoceros hornbill (Becerous rhinoceros) is very large and mainly black with a white belly and tail marked with broad black band. Large upturned casque is reddish and bill yellow, and is lighter in color on the female. They are found in the extreme south of Thailand in evergreen forests from lowlands up to 1,200 meters, and are a rare resident.

11) Great hornbill (Becerous bicornis) is very large and is easily recognized by golden-stained white wing bar and white trailing edge to wing and by white tail with black band. Red eye in males and white eye in females. Mainly with a yellow bill and casque. They are found in evergreen and mixed deciduous forest from plains up to 1,500 meters and found on some offshore islands. Uncommon to locally common residents.

12) Helmeted hornbill (Rhinoplax vigil) is large with a elongated central tail feathers. Blackish brown with a white belly. Short conical bill and rounded casque is red. They are found in evergreen forests from plains up to 1,200 meters and is, an uncommon to rare resident.

Gurney’s Pitta – The last few stragglers

WILD SPECIES REPORT

Avian fauna on the brink of extinction in Thailand

Gurney’s pitta male – one of the last few surviving birds at Khao Nor Chuchi

In October 2001, I did a story entitled ‘On the verge of extinction’ for the Bangkok Post Nature section about an amazing bird that had been rediscovered in 1986 by my close friend and associate Phillip D. Round, Thailand’s eminent ornithologist after almost three decades of no sightings. Prior to that, it was thought to be extinct in the Kingdom. The bird was listed as a flagship species for conservation and put on Thailand’s 15 reserved species list.

The Gurney’s pitta Pitta gurneyi is a medium-sized passerine bird that completely disappeared from all lowland evergreen forest south of Prachuap Khirikhan province where natural forest was destroyed primarily to grow palm and rubber trees except for one little patch in Krabi province. This site is known as Khao Nor Chuchi or Khao Pra-Bang Khram Wildlife Sanctuary – the only known place in Thailand where this rare pitta still survived. The area definitely needed extreme management to save this creature from extinction.

A Gurney’s pitta female in Khao Nor Chuchi

In historic times, the range of the Gurney’s pitta was along the coast and inland areas on both sides of the Thai peninsula, in the provinces of Trang and Krabi on the western side, and Nakhon Si Thammarat, Surat Thani, Chumphon up to Prachuap Khirikhan on the east.

It also survived in southern Burma where this beautiful bird was first discovered way back in 1875 by a wildlife specimen collector working for Allan Octavian Hume, a prominent ornithologist. The exotic bird was named rather prosaically after Hume’s friend, J.H. Gurney, a Fellow of the Zoological Society of London.

Lowland rainforests up to 200 meters above sea level are home to an unsurpassed diversity of flora and fauna including the Gurney’s. Due to excessive human settlement and agriculture, this unique bird has diminished to the point of no return here in Thailand.

A male Gurney’s pitta photographed is 2001

Encroachment and forest destruction has not been the lone evil. Some poaching of the Gurney’s for the black market trade have also taken its toll. It is said a pair of a male and female fetches a hundred thousand baht or more from rich collectors of exotic birds at the infamous Chatuchak Market in Bangkok. In fact, the bird’s beauty has been its worst enemy. Even though protection and enforcement has improved over the years, catching the big traders and buyers of wildlife black market items has been slow and sometimes non-existent at times.

However, over in Burma, thousands of Gurney’s are purported to survive after quite a few surveys since early 2003 when Jonathan Eames with BirdLife International and other associates found the bird at four different sites. Jonathan returned in 2004 and found more locations with the bird but political instability and very restrictive government regulations threaten to keep researchers away, while landmines and bandits further discourage access.

Since then, Dr Paul Donald of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) has surveyed many areas and confirmed that almost all of the world’s population of Gurney’s pitta is located in Myanmar but the forests there are also being decimated for palm and rubber agriculture and hence, the bird there is still under serious threat. This granted the species a reassessment from the IUCN, going from critically endangered to endangered.

Hooded pitta with worms feeding its chicks somewhere in the forest

My first encounter with a Gurney’s was back in 2001 when I made an effort to capture this bird on film. The following is an account of that wonderful moment that was very brief, and I only managed to get one shot shown in the story.

“Dark morning stillness in thick lowland rainforest is broken by muffled footsteps as two humans move slowly down the trail. We carry heavy camera equipment to a photographic blind erected deep in the jungle the previous evening. Condensation is heavy as I set up in the hide. My friend and guide, Douglas Judell departs quickly and noisily – the intent being to convey the message that both of us have left the area.

As animals of the night retreat, I wait for the first signs of dawn. My goal is to photograph this elusive pitta known to frequent this small patch of forest. Morning light awakens the jungle and the sounds of dripping moisture begin to be replaced by the noise of birds and insects starting their day. Hidden in the blind, I remain vigilant for the slightest movement on the forest floor. About 8am, light from the sun filters through the canopy in patches.

One of several hooded pittas that showed-up looking for earthworms

A sudden movement shows a hooded pitta, another species common here, hopping about looking for earthworms. This striking blue, green and red bird with a dark brown crown moves closer to the blind seemingly oblivious to the looming structure. Snapping only a few shots for fear of alarming the other denizens of this forest, I continue to sit quietly hoping the ‘forest spirits’ will answer my wish.

A passing morning rain shower quickly passes by and as if on cue, a blue, black and yellow bird suddenly appears in front of the blind about five meters away. Perhaps sensing danger, it quickly hops into the darkness of the forest but a minute later returns just long enough for only one shot of this rare bird. I quickly forgot about the wet grubby conditions and the long road trip of more than 700 kilometers from Bangkok to this place. I was elated to say the least.”

My first Gurney’s pitta male photographed by ‘U’ trail

When I did the story in 2001, there were about 11 pairs and some individuals left in the sanctuary. The decline was evident and it became a worry for the Department of National Parks (DNP). Drastic measures were needed but they never came. When Khao Pra-Bang Khram was up-graded in 1987 by the Royal Forest Department (RFD) from a non-hunting area to a wildlife sanctuary, most of the forest where the bird was actually found unfortunately was not included in the protected area. It is a wonder how things sometimes come to pass.

This then became a pitched battle between conservationists, local villagers and the DNP. Forests were being cleared for palm and rubber and there was nothing the department or NGOs’ could do in certain areas because this land was outside the sanctuary and was the property of the locals. Forest destruction was severe and it put a terrible strain on the ecosystem.

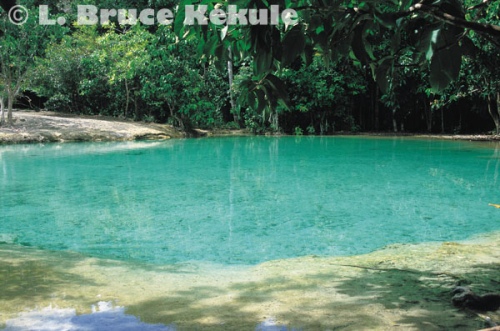

Emerald pond algae not far from the sanctuary headquarters

Another very negative aspect is the visitation by hundreds of tourists almost daily at the Emerald Pond not far from the core area. This place use to be peaceful and beautiful, and a decade ago there were just a few noodle stands and trinket shops at the front. Now this has expanded 100 percent and has become a big business catering to the visitors. Buses and vans are parked everywhere. There are very few birds around the pond now and trash is a serious problem.

Two weeks ago, I made one last ditch effort to photograph this bird. Permission to enter the sanctuary was graciously given by the Wildlife Conservation Division at DNP in Bangkok. I packed-up my old pickup truck and headed South to the small village in Krabi province named Ban Bang Tieo where the sanctuary headquarters is situated.

I met with the new superintendent Nikom Srilamoon of Khao Pra-Bang Khram, requesting authorization to enter the sensitive area in order to catch the Gurney’s on digital. He has certainly inherited a tough job!

Emerald Pond in Khao Pra-Bang Khram

The first day was comprised of walking the nature trails ‘U’ and ‘N’ where the bird is normally found to see first hand the situation on the ground. Many parts are, overcome by humans and their destructive vises of throwing trash on the ground and cutting trees down. Someone has established a rubber plantation in the remaining core area of the sanctuary. Motorcycle tracks are everywhere and it is said spot-lighting for night creatures like frogs and mouse deer goes on. It seems that just about every square meter is under threat.

The next morning, I decided to set-up a quick blind in a palm plantation that borders forest early the next morning at first light. About 7am, a couple female pitta skirted the forest for a couple of meters and then melted back into the thick vegetation. I did not get a shot, as they were too quick.

Palm oil plantation butted-up to the forest in Khao Pra-Bang Khram

In the afternoon, I went back into the trail system to scout a new location. I chose to erect a blind in a gulley with a stream that cuts through the habitat. Sharp thorns are everywhere but it is very secluded from the main nature trails and excessive activity.

The following morning I was sitting alone in the dripping forest at 5.30am sharp. My two helpers departed quickly after installing a slave flash on a tree to the left of my position. Then the rain started and did not let up until late afternoon when the sun finally peaked through the clouds for a short period.

Another male photographed in the sanctuary

Birds immediately began calling and activity picked up. Then, I saw movement ahead and a male Gurney’s popped out of the forest and stayed in front of the blind for only a few seconds as I fired off a short burst including the lead photo. It was exciting, and will be etched in memory. These creatures are still surviving here but they are now hard to locate and stay elusive for the most part. I thanked the ‘spirits of the forest’ for this rare encounter, and the rain came again till just before darkness.

BirdLife International, BirdLife Denmark, DANCED, Bird Conservation Society of Thailand, the Oriental Bird Club and the RSPB have helped the DNP to implement numerous projects at Khao Nor Chuchi, but these efforts have only slowed rather than halted new settlements and the destruction of the forest.

Banded pitta male at Khao Nor Chuchi

The population of Gurney’s pitta at Khao Nor Chuchi has declined drastically, dropping from an estimated 40 pairs in 1986 down to about 20 pairs in the mid-1990s’. At one abandoned nest, local researchers found bird (mist) nets placed by some people to capture this rare bird. The last estimate from various sources on the number of birds is less than ten individuals (both male and female) survive in the core area. This is serious and the prospect of extinction is truly depressing.

Banded pitta female at Khao Nor Chuchi

Unless Khao Pra-Bang Khram protection and enforcement can be quickly implemented and expanded to include all the remaining intact lowland forest, and previously cleared areas are reforested, the species in Thailand faces a very bleak future. Quick and decisive action is the only remedy and it is absolutely no use pointing the finger of blame on anyone.

As a flagship species for the conservation of southern Thailand’s lowland rainforest, only time will tell if the Gurney’s pitta can survive. If this beautiful creature disappears, it will be a sad day for nature conservation in the Kingdom.

THAILAND’S 15 RESERVED SPECIES

Thailand’s list of 15 reserved species is so out-dated it is now covered in dust and needs updating. Two lists should be established: one for species that are truly extinct in the wild, and another list for rare creatures like tiger, leopard, gaur, banteng, Asian elephant, Asiatic bear and sun bear plus the remaining survivors shown below. There are also many other wild animals that need special status!

1) White-eyed river martin: Presumed extinct globally since 1985-86. The last known specimens were from Bueng Boraphet Non-hunting Area in Nakhon Sawan province.

2) Javan rhino: Once found in many large forests and now extinct in Thailand for more than 25 years.

3) Sumatran rhino: Extinct in Thailand for more than a decade or two. A few individuals were reported in Hala-Bala Wildlife Sanctuary. down south in Narathiwat province.

4) Kouprey or grey ox: Extinct in northeasternThailand for at least 30-50 years and absolutely no reports from Cambodia although extensive surveys have been carried out. The Khmer Rouge during wartime is probably responsible for their demise.

5) Dugong or sea cow: Extremely endangered in the seas of Thailand. There are a few survivors but are probably doomed by excessive fishing and tourism.

6) Wild water buffalo or Asiatic buffalo: Endangered with about 50 individuals surviving in only one location: Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in western Thailand.

7) Eld’s deer: There are two sub-species (Siamensis and the Burmese) and both are extinct in the wild of Thailand.

8) Schomburgk’s deer: Extinct globally since 1935. They were endemic to the Central Plains of Thailand and the last one was killed in a temple in Samut Prakan by a village drunk in 1932. Sad fact!

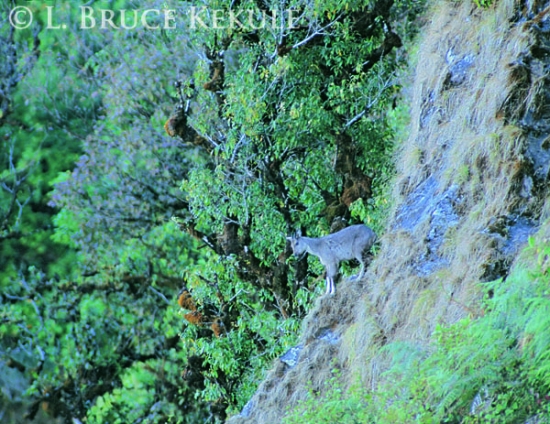

9) Serow: These goat antelopes are endangered but they still survive in some mountaInous areas that are protected. Their horns are eagerly sought after and used in making knives for fighting cocks in the South.

10) Chinese goral or grey tailed goral: These goat antelopes are seriously endangered; a couple of hundred might live on mountaintops in northern Thailand.

11) Gurney’s pitta or black-breasted pitta: They are technically extinct in Thailand. There are a few individuals surviving in Khao Phra-Bang Kram Wildlife Sanctuary in Krabi.

12) Eastern Sarus crane: Extinct in Thailand for more than 50 years. They do survive in Vietnam and Cambodia but their numbers are low.

13) Marbled cat: They still survive in the thick evergreen forests of Thailand but their numbers are unknown.

14) Asian or Malayan tapir: They still survive in the western flank of Thailand from Thung Yai Naresuan WS all the way down to Malaysia. However, they are hunted for bush meat in many places in the South.

15) Fea’s muntjac: They still survive in the western flank of Thailand from Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary all the way down to Phang Nga and Surat Thani in the South, and are hunted for meat throughout their range.

PLEASE NOTE:

While I was researching the Gurney’s Pitta on the web, I found a resort website in Krabi using my ‘first’ Gurney’s pitta photograph with out my permission. On photographs of great importance, I will now be using a new watermark covering the subject matter with my name and copyright. I regret this action but do not appreciate people stealing my photographs off the web for their own business purposes. These people have no professional ethics!

CREDIT FOR PHOTOGRAPHS

I would like to thank my good friend Kanit Khanikul for the use of his photographs of Gurney’s and Banded pittas. He certainly has one of the best collections of birds from Khao Nor Chuchi in Thailand and he has spent a lot of time and money recording avian fauna there. He should be praised for his great work!

Realm of the Angel Horse

Goral and Serow: Thailand’s rare goat-antelopes

Endangered ungulates surviving on forested mountaintops

Goral kid in Doi Inthanon National Park

For centuries, northern Thai people called them ‘angel horse’ or ma tewada referring to angelic creatures living on mist-shrouded mountains. Goral are even-toed ungulates of the bovid family that includes pig, deer, goat and antelope. They are one of two goat-antelope species found on forested peaks and limestone karst formations that jut from the landscape.

The other goat-antelope is the serow, a larger bovid but found throughout the Kingdom from the north to the south, and east to the west. They mingle with the smaller goral at some locations in the North, primarily in the protected areas. Goral, on the other hand is found only from Tak province up to the border of Burma on the western flank.

Serow male camera-trapped in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Photographing endangered wildlife species has become a bit of an obsession to me. Many of Thailand’s animals have come so close to extinction that their numbers are not counted in thousands or even hundreds but mere handfuls at some locations. Both species are extremely endangered especially the goral.

I have photographed goral and serow in their environment but it is fraught by danger due to the sheer cliffs and rocky terrain where they live. On some tracks, one miss-step could end up in disaster. Goat trails worn over thousands of years are engraved on steep mountains throughout the country even though most of these bovid have disappeared from the habitat. Unfortunately, protection and enforcement came a bit too late!

Goral and serow habitat in Doi Inthanon

But the evidence of their past existence still remains. Over the years, I have walked these deeply rutted tracks in the North. At one time, there were absolutely thousands of these goats in the wild.

The estimated population of goral in the country is now about 200-300 individuals based on several recent surveys carried out be the Department of National Parks (DNP) where the goats remained. Some fifteen years ago, only 60 were documented in 6-7 protected areas.

Sunset in Doi Inthanon National Park

Goral are now found in 19 sites as follows: Mae Ping, Doi Inthanon, Ob Luang, Pha Dang, Doi Fas Hum Puk, Namtuk Maesurin, Tumpla-Namtukphasuay, Sisatchanalai, Doi Jong, Sri Lanna national parks, and Omkoi, Mae Tuen, Salween, Chiang Dao, Mae Lao-Mae Sae, Doi Wing La, Doi Luang, Sun Pun Dang, Lum Nam Pai wildlife sanctuaries.

Mae Lao-Mae Sae Wildlife Sanctuary