Posts Tagged ‘Large Mammals’

The Big Six: Large Dangerous Mammals of Africa and Asia

Africa’s Big Five…!

The ‘Big Five’ was coined by colonialists in East Africa by the big-game hunters sometime in the 1850s, and was trophies collected from large dangerous mammals taken with a gun. Photography was in its infant stage and very few photographs of wild animals in their natural habitat were around other than pictures of downed animals on the ground with the trophy hunter and gun bearers standing by its side.

Bull elephant in Tsavo West National Park, Kenya, during the late afternoon. This huge bull came real close to the car but passed by without incident. This was the largest tusker I had ever seen on my four safaries through 11 protected areas. Truly, a ‘wildlife icon’ of Kenya’s natural heritage. Taken with a Nikon D7000 and a 70-300 VRII lens @ 116mm. Offhand through the window.

Many rich and famous people went on safari to the ‘Dark Continent’ as it was called back then including Theodore Roosevelt, President of America and Queen Elizabeth II of Britain, plus many Hollywood movies stars like Clark Gable, Ava Gardner, Grace Kelly and Stewart Granger. Going on safari was big business just after the turn of the 20th century, and usually only the ‘well-to-do’ could afford such a journey. They came from all around the world to hunt the large animals that were thriving in great numbers on the savannas and in the bush.

The ‘Big Five’ list consisted of the elephant, rhino (black and white), Cape buffalo, lion and leopard. Most hunters used large caliber rifles to bring down these mighty beasts as trophies to be hung on a wall, or a rug on the floor in the office or home. Other parts of some creatures ended up as trash cans, ashtrays, lampshades and jewelry to name just a few. This was way before cameras came into vogue to capture these animals on film and eventually digital.

White rhino mother and calves in Lake Nakuru National Park not far from Mount Kenya in the central region. This species is identified by their wide mouth and were reintroduced from South Africa as Kenya had lost most of its rhinos to legal hunting and illegal poaching for the horn. Taken with a Nikon D3s and a Nikon 400mm ƒ2.8 on a beanbag.

Black rhino mother and calf in Nairobi National Park, Kenya. Part of the city of Nairobi is in the background and there are about 60 black rhinos trans-located from South Africa to this park. Taken with a Nikon D3s and a Nikon 200-400mm @ 650mm on a monopod…!

Cape buffalo in Tsavo East National Park, Southern Kenya. Note reddish color of this very mature bull due to red clay found in the area. Buffalo found in other areas of Kenya are mostly black. Taken with a Nikon D7000 and a Nikon 70-300mm VR II lens @ 220mm on a beanbag.

A black-maned lion in Taita Wildlife Sanctuary near Tsavo West National Park. This big cat was caught in the grassland just before the park closed for the day around 5:50pm. It was a lucky encounter. Taken with a Nikon D3s and a Nikon 200-400 VR II lens and a 2X teleconverter for 800mm on a bean-bag.

Leopard in the Masai Mara National Reserve in western Kenya. This big cat was seen and photographed on my very first day while on safari in this protected area. This was a real good start to capture the ‘Big Five’ of Africa as the leopard is the hardest to photograph in the group. Taken with a Nikon D3s and a Nikon 400mm ƒ2.8 lens on a beanbag.

Thailand’s Big Six…!

For the last twenty years, I have photographed all of Thailand’s large mammals including elephant, gaur, banteng, wild water buffalo plus tiger and leopard. It has been an excellent journey and experience for me, and I feel fortunate to have been at the right time and right place to capture these wild animals with my camera.

A tusker by the river in Sai Yok National Park in the Western Forest Complex. This shot was taken while he was fanning himself more than a decade ago and it is doubtful this big elephant is still surviving. Poachers chase after these elephants for their ivory just like everywhere else jumbos live. Taken with a Nikon F5 and a Nikon 500 P manual lens using Fuji Provia 100 slide film.

A small herd of gaur in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Surat Thani province down in Southern Thailand. These herbivores thrive quite well here in this protected area along the shoreline of Khlong Saeng reservoir. This was taken with Nikon D3 and a Nikon 400 ƒ2.8 lens on a tripod setup in a boat.

Very mature banteng bull and cow at a mineral deposit in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in the Western Forest Complex. These herbivores thrive very well in this protected area and there are estimated that more than 350 are found here. Taken with a Konica Minolta Dynax 7D and a Minolta 600mm lens from a photo blind across the river.

A wild water buffalo cow charging me by the river in Huai Kha Khaeng in the Western Forest Complex of Western Thailand. This female was part of a small herd wallowing in the waterway. Taken with a Nikon D2x and Nikon 400mm ƒ2.8 lens on a tripod mount from a boat-blind.

An Indochinese tiger at a waterhole in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in the Western Forest Complex of Thailand. There are about 200-250 tigers left in the forests in the East and West and some in the South. They are highly sought after by poachers for tiger body parts, bones and pelt. This male tiger was caught by Nikon D700 and Nikon 400mm ƒ2.8 lens from an elevated blind.

An Asian leopard crossing a fallen log in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in the Western Forest Complex of Thailand. This male cat was captured using a Nikon D700 trail camera with a Nikon 35mm lens and two Nikon flashes. These big cats are fairly common in this protected area and both color phases (black and yellow) can be found here.

A black leopard walking in the afternoon sun catching its spots at a hot spring in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in the Western Forest Complex. This mature cat stayed for more than an hour waiting on prey. This was taken with a Nikon N90s with a 500mm ƒ4 lens using Fuji Provia 100 slide film.

Africa’s Big Six…!

Then in 2010, 2011 and 2012, I made four trips to Kenya in Africa and collected images from ten protected areas including the Masai Mara National Reserve that was first on the list, followed by Lake Nakuru, Samburu, Amboseli, Tsavo East and Tsavo West national parks, Taita and Shimba Hills wildlife sanctuaries, Sweetwaters private reserve and finally, Nairobi National Park capturing the ‘The Big Six’ which includes the elephant, rhino, buffalo, lion, leopard and hippo while on safari. The hippo is included in this list because they take a serious toll on humans that get in their way and are one of the most dangerous animals in Africa. Kenya has done a great job in preserving its wildlife heritage and hopefully one day I will return.

Elephant in Taita Wildlife Sanctuary in Southern Kenya between Tasvo East and West national parks. The large mammals in this area are mainly red colored due to the red clay found here. Taken with a Nikon D3s and a Nikon 600mm ƒ4 lens on a bean-bag.

Black rhino male in Nairobi National Park just outside Nairobi city in Kenya. These odd-toed ungulates were introduced from South Africa and now there are about 60 of them found here. Taken with a Nikon D700 and Nikon 200-400mm lens on a bean-bag.

White rhino in Nairobi National Park close to the Nairobi city in the background. These herbivores are now found in good numbers and were also introduced from South Africa. Taken with a Nikon D3s and Nikon 400mm ƒ2.8 lens on a bean-bag.

A Cape buffalo down in Shimba Hills Wildlife Sanctuary near Mombassa, Kenya. Due to the moist evergreen forest with loads of rain found here, the large mammals like buffalo and elephants are dark in color compared to their cousin further north that take on a red hue. Taken with a Nikon D7000 and a Nikon 70-300mm lens on a bean-bag.

A lion cub close to the road at dusk in Tsavo West National Park. These carnivores are found in good numbers here as the prey base is also good. Taken with a Nikon D3s and Nikon 600mm ƒ4 lens on a bean-bag.

A mother leopard in the Masai Mara National Reserve in Western Kenya. These carnivores thrive as prey species is very good in this protected area. Taken with a Nikon D3s and a Nikon 400mm ƒ2.8 lens on a bean-bag.

A male hippo in Tsavo West National Park in Southern Kenya. These huge herbivores live around large waterholes found in the park. They are dangerous mammals and more people die from hippo attacks then all the other big animals put together. Taken with Nikon D3s and a Nikon 600mm ƒ4 lens on a bean-bag.

India’s Big Six…!

India was next on my radar and my first trip happened in April 2013, then again in November 2014 and two trips last year (Feb-Mar & November, 2015). So far, I have visited the most famous protected areas in India consisting of Kaziranga, Ranthambore, Bandhavgarh, Corbett, Tadoba, Kanha, Pench and Satpura national parks and tiger reserves. The ‘Big Six’ list includes elephant, Indian rhino, wild water buffalo, gaur, tiger and the leopard were photographed.

Hunting back in the old days was carried out primarily by the British and India’s Royal Maharajahs, which almost wiped out many species especially the tiger. However, the country has done an amazing job of saving this species from the brink of extinction for people from around the world to see and enjoy. The balance of nature is still fairly intact and these creatures still thrive on the sub-continent in good numbers.

Bull elephant at a waterhole in Kaziranga National Park and Tiger Reserve in Assam State, Northeastern India. There are some 1,000 of these herbivores found in the park. Taken with a Nikon D3s and a Nikon 200-400mm lens on a mono-pod.

A male Indian one-horned rhino in Kaziranga National Park and Tiger Reserve. There are roughly 2,400 rhinos now and is one of the greatest conservation success stories in the world. Some 80 years ago, there were a mere 12 remaining and the Assamese government established a ‘shoot-to-kill’ policy for any poachers found in the park. Taken with a Nikon D3s and Nikon 200-400mm lens on a mono-pod.

A wild water buffalo in a waterhole in the park with huge horns. These herbivores have the largest horns in the world. There are some 1,300 buffalo found here and is one of the largest herds in the world. Taken with Nikon D3s and a Nikon 200-400mm lens on a mono-pod.

A bull gaur in Kanha National Park and Tiger Reserve, Central India. These even-toed ungulates are the largest bovine in the world standing 1.7 meters at the shoulder. Taken with a Nikon D3s and a Nikon 200-400mm lens on a mono-pod.

A male tiger named ‘Wagdoh’ (one-eye) in Tadoba Anhari Wildlife Sanctuary in Central India. There are about 2,400 tigers in India’s protected areas and is the largest population in the world. Taken with a Nikon D3s and a Nikon 200-400mm lens on a mono-pod.

A female leopard in late morning in Tadoba Anhari National Park, Central India. For the most part, leopards are tough to spot in the forests of India. However, luck does come and this beautiful girl posed for my camera on my first morning safari in March 2015. Taken with a Nikon D3s and a Nikon 200-400mm lens on a mono-pod.

In 1995, I began what will be my last profession in life when I picked up a camera some two decades ago. Photographing wildlife is the greatest thing I have ever accomplished in my 70-odd years on the planet. It has been a journey of discovery and rediscovery, and sometimes I wish I could have started wildlife photography when I first came to Thailand in 1964. The jungles and teak forests were absolutely teaming with wild creatures from Asian elephants down to tree shrews. Birds, reptiles, amphibians plus insects and spiders were also found in great numbers.

Conclusion: It is my opinion and utmost worry that some of these ecosystems and large mammals found in Thailand, Kenya and India are in jeopardy from human influences. Certain species have gone into serious decline or have even become locally extinct due to the human population explosion, and expansion into these wild places. Therefore, more is needed to protect and save the natural wonders of ‘Planet Earth’ from annihilation by the human element before it is too late. A thousand percent increase in preservation, forest management, more personnel and rangers on the ground plus more funds is the only answer. But with so many obstacles in the mix, I remain optimistic about wildlife in many forests of the future. As the natural biospheres undergo serious threats and changes to their integrity by humans, the road to extinction is at hand for many.

However, saving wildlife and the protected areas where they live with good security and enforcement must be implemented and is the key to the animal’s future survival in places like Kaziranga National Park in Assam, northeast India. Here, most guards are armed with a .303 service rifle and extreme measures are upheld to the letter; poachers are dealt with swiftly and in a deadly manner in some cases. Because of the stringent rules and protection, there are 2,400 Great Indian rhino, 1,300 wild water buffalo, 1,000 elephant and one of the highest tiger densities in the world with over 100 big cats living in a smallish (840 sq. kilometers) park. Kaziranga is the true role-model for real wildlife conservation around the world in desperate times. As more and more creatures disappear from the wild, tougher rules and regulations is the only way to guarantee their future survival…!

Canon 400D catches an old Asian tapir and clouded leopard

Southern Thailand’s natural heritage – an odd-toed ungulate and a carnivore

A mature Asian tapir caught by a Canon 400D trail cam…!

Just returned from Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary in the south of Thailand and pulled my Canon 400D camera trap. These shots are of an old Asian Tapir and the best ones in this set as shown here. Being odd-toed ungulates and strictly vegetarian, these large herbivorous mammals thrive quite well in this unique ecosystem made up of moist evergreen forest. These unique creatures have been on the planet for about 40 million years. They are the largest of the world’s four species with the other three in South America…!

This tapir almost looks pregnant…!

A clouded leopard in daylight…!

This cam also caught a clouded leopard but the cat came in a bit low. These cats are not normally out in broad daylight but I guess they do sometimes prowl during the day. That was the trade off for the full-frame tapir shot. This sanctuary is simply amazing and I look forward to future visits…! Enjoy…!

Thailand’s Vanishing Giants

A family unit in Khao Yai National Park.

Increasingly dangerous environment for wild elephants: An indicator species of a pristine forest

Of all the mammals in Thailand, the wild elephant is probably the most important indicator species of a disappearing wilderness. A century ago, there were more than a hundred thousand elephants found in the country when 75 percent of the Kingdom was still covered by forest. Just north and east of Bangkok, these huge mammals thrived in the marshlands and forests near the city.

But as time passed and humanity expanded creating cities and towns, roads and highways, railways, agriculture farmlands, golf courses and resorts, the home of the wild elephant began to disappear leaving many forests fragmentized and degraded. Populations of wild elephants went into serious decline. Humans are directly responsible for this loss with encroachment and poaching at the forefront. Forests and wildlife continue to disappear as we move into the 21st Century.

When Khao Yai, the first national park in Thailand was established in 1962, the Royal Forest Department (RFD) was in charge of protecting the forest. Prior to that, they controlled logging concessions and huge swathes of forest were felled in the timber business. Finally, the government stopped all logging in 1989. However, illegal tree felling is still going on to this day but on a smaller scale.

Tusker camera trapped in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary, eastern Thailand.

Then in 1992, the Department of National Parks (DNP) was established to look after the national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, non-hunting areas and marine national parks. There are now over two hundred protected areas nation-wide.

Since then, it has taken many, many years for the department to establish some form of protection and enforcement. Patrolling of the forests has been minimal due to many factors. Unfortunately, things have been difficult for them to look after these biospheres because of low budgets and not enough personnel. Laws are seriously outdated especially when it comes to elephants.

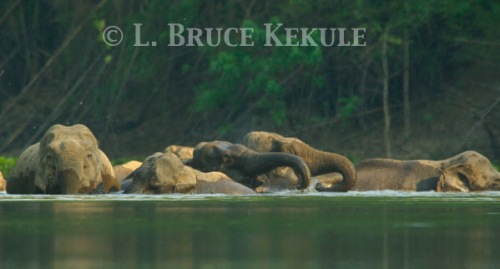

Elephants in the Huai Kha Khaeng river blowing water.

The history of man and elephants in Asia has been intertwined for several thousand years. These majestic creatures taken from the wild have been part of human culture and beliefs. Elephants played a major role in the wars with Burma of the past. Until recently, the elephant was not only used for logging but for transport and baggage. More recently, they are used to attract tourists at camps and in cities where people use them for begging. The domestic elephant has been abused, and very badly in some cases.

Begging elephant in Chiang Mai – Abstract.

Probably the most appalling fate for a domesticated elephant is to become a streetwalker. These magnificent creatures are forced to walk hot, dusty and polluted streets of Thai cities ‘begging’ for food and money. Stories about elephants hit by cars and falling into drainage ditches, plus other accidents have been documented.

Ten years ago, it was guesstimated that 2,000 wild and 3,000 domestic elephants were thriving in the country. Due to an increased DNP and NGO interaction in the parks and sanctuaries, wild elephants have made a bit of a comeback in some protected areas. There are now (still guesstimated) to be about 3,000 wild elephants and more than 4,000 domesticated animals. Population density surveys have been carried out in some parks but exact numbers of the wild population are still uncertain.

Elephants on a truck bound for Chiang Mai.

The biggest threat to wild elephants is still the same. Poaching males for their ivory and females for their babies. Recent kills in Kaeng Krachan National Park in the Southwest have gone on for quite sometime due to poor protection and enforcement, and numbers of elephants have dropped.

Elephants in the savanna of Kui Buri National Park.

It is quite possible that they have migrated to Kui Buri National Park further south along a thin corridor along the Burmese border. Numbers in Kui Buri have increased 100 percent in the last five to ten years, and evidence of elephants in Prak Tha Kor Reserve Forest between the two parks has been documented. This area needs to be established as a protected area.

Elephant herd in Kui Buri National Park.

The following is a typical scenario of baby elephant snatching. Gunshots reverberate explosively through the forest, panicking and scattering a herd of wild elephants. The huge beasts instinctively flee as fast as they can through heavy foliage away from the cacophony. In minutes, the forest returns to normal. But the sad fact is that humans have just disrupted the herd permanently.

A large herd in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary.

A baby elephant mills aimlessly around its mother lying dead on the ground. The confused calf has no sense of danger as poachers move in to capture it to be sold on the illegal black market. The calf will likely be forced to wander city streets or work in tourist camps.

A small herd including a calf in the Huai Kha Khaeng river.

Such atrocities are still practiced by unscrupulous people intent on killing the mother solely to capture the baby. Many other animals are also hunted down in much the same way. Middleman, the ‘big-fish’ and end-use buyers perpetuate this market and seem to evade the law. When will this horror story ever stop?

A tusker and tourists in Khao Yai.

In another real-life scenario, a young tusker is killed on the road that transects the northern part of the elephant’s range in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary in eastern Thailand. It is home to about 170 wild elephants. The road had been widened and resurfaced to enable faster speed.

Tuskless bull in Huai Kha Khaeng.

During late-evening one day in May 2002, a man and woman in a pickup truck barreling through the sanctuary at high speed did not see the elephants on the road until it was too late. The truck crashed head-on into a 5-year-old tusker. The truck’s driver was killed on impact but the woman survived. The young elephant died shortly after.

Tusker on the road in Khao Yai NP.

This young tusker was not the first and definitely will not be the last elephant to be killed by reckless driving on this road. Eventually, the local government ordered the road closed through Khao Ang Rue Nai from 9pm to 5am. The elephants come out of the forest usually only at night and can now roam safely in their own habitat. Accidents and road-kill have dropped drastically. Definitely a role model for other protected areas with elephant-human conflicts.

Another tusker on the road in Khao Yai N.P.

Such accidents are a terrible blow to the conservation of Thai elephants, because tuskers are particularly vulnerable, being subject to hunting for their ivory. Asian ivory is finer-grained than African ivory and prized for carving into trinkets and Japanese hanko (signature seals).

Herd in Kui Buri N.P.

Much of their habitat has been taken over, mainly by pineapple, sugarcane and cassava. Villages spring up in old elephant habitat, and the trespassers expect the giants to simply fade away into the forest. But elephants can develop a taste for crops grown by farmers, and they often take what they want. Countless conflicts have arisen between villagers and the real owners of the land, whose ancestors have lived there for many thousands of years.

Herd in the Huai Kha Khaeng river.

Elephants have been maimed and killed by poisoning waterholes, pungee stakes, gunshots, and electrocution. They have been chased out of rice paddies, mango orchards and farmlands. People use fireworks, bright lights and guns to scare them away temporarily, but the elephants are intelligent enough to lose their fear of such ruses.

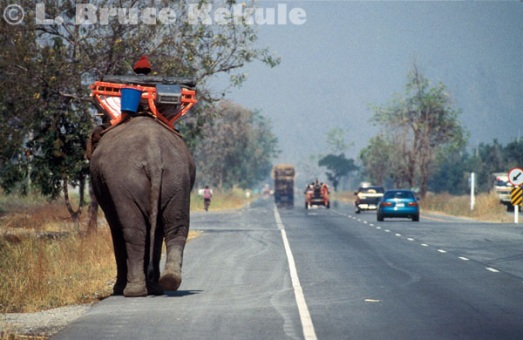

Elephant on the highway north of Bangkok.

These giants grow bolder and go on the rampage, sometimes killing people, tearing up villages and damaging RFD and DNP facilities. Some conservation organizations have erected new signs warning of the danger of elephants in the area.

Elephant and handler begging near ‘700 Years’ Stadium in Chiang Mai.

A trip at night around some cities, one can still be greeted by a huge gray beast with a red light attached to its tail. Continuous calls for change go unnoticed by mahouts and the owners of these elephants who sneak them into tourist sites. Legislation concerning domesticated elephants remains old and out-dated, and law enforcement has also been very poor. On the positive side of things, the authorities have finally moved them out of Bangkok, but they still roam on the outskirts in some places.

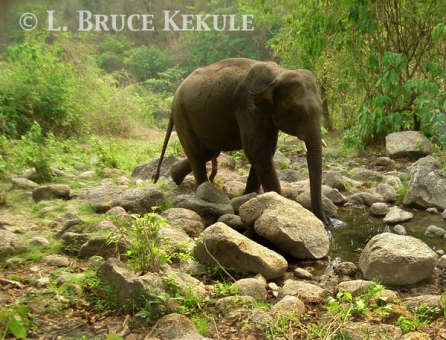

Elephant in a mineral deposit in Kaeng Krachan N.P.

It is hoped that the RFD, DNP and other government organizations will draw attention to the dire situation of Thai elephants, both wild and domestic. These noble beasts have featured prominently in almost every important historical event in the Kingdom. They are a national symbol of pride and joy. The Thai elephants’ future survival lies in the hands of the government who are responsible for these amazing giants….!

Special Note:

I would like to thank Andy Merk, German wildlife photographer for the lead photograph. He has been hanging around Khao Yai for the last 20 some years and has a huge collection of elephant photos from the park. He is doing a survey of trying to get a estimate of the population by identifying individual elephants by their ears, specially the male tuskers and mature females.

The ‘Little Elephant Slider’

A 3-month old baby elephant slides in on the trail to a waterhole deep in the forests of western Thailand. This family unit is also made-up of several mature females and younger juveniles.

Living Fossils – A video of Asian tapir

Rare daytime footage of Asian Tapir

Tapir are considered living fossils as the genus has been traced back as far as Early Oligocene times. These remarkable mammals have been on the planet for about 40 million years. The first tapirs are named Miotapirus judging from fossil evidence found in North America. Tapiridae, a sub-family belong to the Order Perissodactyls, or odd-toed ungulates that goes back to the Late Paleocene 55 million years ago including rhinoceros-like creatures evolving in North America and eastern Asia from small animals similar to the first horses.

The Asian tapir Tapirus indicus, also called the Malayan tapir, is the only one native to Southeast Asia. It has an unmistakable black and white two-tone pattern distinguishing it from the other three tapir species of Central and South America. The Asian species is the largest, and is the only ‘Old World’ tapir with the females usually slightly larger than the males. They live in the rainforests of Thailand, Myanmar, Malaysia and Sumatra.

This old male and female tapir visited this site more than once over two days. Most of the footage was captured by a Bushnell HD Trophy Cam, and the IR clip by a Ron Davis DXG 125v IR homebrew cam.

Thailand’s Big Seven

WILD SPECIES REPORT

Elephant, gaur, wild water buffalo, banteng, tapir, tiger and leopard

Large Mammals in the Kingdom and the amazing biodiversity of Asian mega-fauna

Asian tapir camera-trapped in Huai Kha Khaeng

The term Big Five has always been recognized as an African thing with elephant, rhino, buffalo, lion and leopard making up the group. In fact, the hippo and the Nile crocodile should also be included as the most awesome animals on the African Continent. These large creatures have always fascinated people interested in nature.

The Big Five was hunting terminology for bagging these beautiful creatures with a gun, and then showing off the trophies and hunting photographs in their homes or offices to family, friends and associates. To come face to face with these sometimes ill-tempered beasts, mostly on the ground, was the ultimate test for the affluent hunters who visited Africa, and was the Holy Grail if they managed to bag all of them, so to say.

Young bull gaur in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

The ‘black-mane lion’ of the Maasai Mara in Kenya was one of the most sought after trophies and at the top of the sportsman’s list. However, hunting and killing of wild animals has somewhat gone out of fashion for most people around the world but it does continue on a limited scale. Those countries in Africa that still allow the huntsman an opportunity to take a trophy are few, and the cost is astronomically expensive plus the negative aspect of the sport, and the killing of these big beasts.

Last year I made a trip to Kenya and managed to bag the Big Five photographically. It was an amazing experience that is etched in memory. But it was from the safety of a safari van as the regulations in the parks and reserves are very strict about leaving the vehicle. But the thrill of seeing and photographing Africa’s wild mammals, birds and reptiles is an amazing experience, and one I recommend to anyone interested is seeing or photographing nature up close.

Bull elephant in Sai Yok National Park

Southeast Asia is also one of the world’s great wildlife treasure houses and maybe not as large or grand as Africa, Thailand’s Big Seven still flourish in a few of the larger protected areas in the Kingdom. This includes elephant, gaur, wild water buffalo, banteng, tapir, tiger and leopard. There is only one place on the planet that has all seven and that is Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Uthai Thani province in the central-west.

A hundred years ago, two species of rhinoceros (Javan and Sumatran) were found in the large forests around the country but unfortunately were completely decimated before the protected areas came into being. A short fifty years ago when Khao Yai National Park was established, the last few stragglers were hunted down and that was the end of rhino in Thailand. Killed for their horns and sold to Chinese medicine dealers and Arab knife makers (used for dagger handles), it was a sad ending to some very captivating mega-fauna.

Banteng bull in Huai Kha Khaeng

Someone in Huai Kha Khaeng once coined the phrase Thailand’s Big Seven and at one time, there were loads of photographs of all these beautiful animals from the sanctuary all over the walls at the Seub Nakhasathien meeting hall in the headquarters. Most of the original photos are now gone but time does moves on. Most up on the walls now are of conservation and research projects, and rangers at work that is also good. Many school children come to this retreat to pay respect to Seub at his spiritual home, and to learn about nature and his life, and the sacrifice he made for Thailand.

After 15 years of visiting and photographing wildlife here including the Big Seven on film and digital, I can say this place is the Kingdom’s finest protected area. The sanctuary is without doubt, one of the best wildlife havens in Southeast Asia, and the world for that matter. However, other parks and sanctuaries have some of the Big Seven but are lacking the buffalo.

Wild water buffalo cows in Huai Kha Khaeng

After publishing individual Wildlife Species Reports in the Bangkok Post on all theses animals over the last couple of years, an up-dated review is warranted. As we forge ahead into the 21st Century, it is apparent these marvelous creatures and protected areas are under serious threat. The more people at all levels of society are educated about Thailand’s natural resources, the better the chances for survival into the future.

Indochinese tiger in Huai Kha Khaeng

This should be the highest priority for the government and private sector. Old out-dated laws and regulations are hampering conservation efforts and need a serious revamp. Wildlife crime is on the increase and concerted efforts to improve protection and enforcement is unfortunately, a bit slow in coming.

Leopard camera-trapped in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Budgets, funding and more rangers and personnel are needed. Transparency is also a must with the national parks and wildlife sanctuary budgets so money is used properly and efficiently, and corruption stamped out completely. Now that will be a tough nut to crack. It is hoped this draconian situation will change, so the Kingdom’s natural heritage will continue to survive in today’s world.

Thailand’s Big Seven

Asian Elephant: Elephas maximus

Asia’s largest terrestrial mammal is slightly smaller than its African cousin but still a huge beast of the forest, and approximately 2,000 survive in the wild of Thailand. These giant herbivores create trails to feeding grounds, mineral licks and migration routes through large tracks of forest. They are a flagship species for conservation.

In the old days, the genetic survival of the elephant depended on its ability to mix with other herds sometimes a long way away. Unfortunately, roads and human settlements have disrupted migration routes, and the poaching of large bulls with big ivory has affected the elephant’s natural breeding ability. As their numbers in the wild diminish, the Thai people should exert more pressure on the ‘powers-to-be’ the need to improve protection and enforcement as it’s number one priority.

Gaur: Bos gaurus

Gaur are wild forest ox and the largest bovid in the world standing 1.7 meters at the shoulder weighing close to a ton for mature bulls. These even-toed ungulates still survive in some protected areas but are in serious decline. It is now estimated about 1000 remain in Thailand. However, some reserves have gaur breeding in fairly good numbers like Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai Naresuan forest complex allowing them to actually increase in number if there is adequate protection.

These enormous beasts live in herds but also become solitary, primarily the males. But I have also seen and photographed mature female gaur alone. Mineral deposits play a very important role in the lives of these wild cattle as does thick forests and steep mountainous terrain with abundant water resources. Their future depends whether they are protected to the fullest extent. Unfortunately, their beautifully curved horns are highly sought after by poachers and people who covet trophies.

Wild water buffalo: Bubalus arnee

These low-slung beasts are certainly the most fearsome of all the wild bovid family in Asia. Once upon a time, they were found all over Thailand in swamps and alluvial rivers. In the old days, wild buffalo were rounded up for domestication and hence disappeared from everywhere except Huai Kha Khaeng where the last wild herd now lives. Their numbers are small and it is estimated that 50-60 thrive in the southern section of the sanctuary.

Human expansion throughout Thailand over the last couple of centuries and the use of this beast of burden was the wild buffalo’s demise. Most were tamed for farming and transportation but the last herd was saved just in the nick of time when the wildlife sanctuary was created in 1972. This herd however is continually threatened with an ever-increasing human population just outside the sanctuary, and the mixing of domestic with wild buffalo by the local farmers is a serious problem with possible transmission of cattle disease like anthrax or foot and mouth. Hunting them for their trophy is also a serious threat.

Banteng: Bos javanicus

Banteng are common ancestors to Bos bibos, wild cattle that inhibited the vast plains of Asia during prehistoric times. Fossil finds of banteng from the Pleistocene epoch in Bali and Java are common. These beautiful red wild cattle thrive well in only two places in Thailand and it is estimated about 250 individuals live in Huai Kha Khaeng in the west, and another 80 or so in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary in the east.

There are a few other small pockets where banteng is still found but these are not sustainable and they will eventually disappear. Protection of their remaining habitat is the most important element. Their horns and meat as with gaur and buffalo are also sought after. Banteng prefer open lowland deciduous forest and are easy pickings for poachers with jeeps, spotlights and rifles. As creatures of habit like gaur, they also need to visit mineral deposits and hence, fall victim to determined hunters.

Asian Tapir: Tapris indicus

The family to which the modern tapir belong, Tapridae, can be traced back as far as Early Oligocene times, about 40 million years ago. Tapir evolved from small hoofed mammals. These odd-toed ungulates eat only vegetation. It is also the largest of the world’s four species. They are solitary creatures unless breeding. The young have longitudinal pale striped bodies but as they grow older, the Asian tapir has a distinctive two-toned black and white coloring.

At one time, tapir could be found throughout the western Tenessarim Range all the way down the Thai Peninsula to Malaysia. That has all changed now due to roads, highways and human settlements that have divided up the country. However, it is estimated that maybe 300-400 still thrive in Thailand. Tapir are poached for their meat in some areas.

Indochinese Tiger Panthera tigres corbetti

The tiger is probably one of the most revered creatures in the animal kingdom and is a flagship species for wildlife conservation. As Asia’s apex predator, it present status is not good. Its current standing is at an all-time low with about 200-300 left in Thai forests if that. Where there are abundant prey species and good protection with no poaching, the big cat will survive and breed.

The Western Forest Complex with Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai at the core is the best tiger habitat in Thailand, and Thap Lan and Pang Sida national parks in the Northeast is Thailand’s second best tiger reserve. Another good location for tiger is Kaeng Krachan and Kui Buri forest complex but their numbers are low here.

Tiger bones are one of the most sought-after wildlife commodities and the pelt is now usually left to rot, as it is very heavy when fresh and difficult to take care of. The Chinese medicine trade is the number one reason tigers have dropped drastically in numbers worldwide, and this responsibility rests directly on China’s shoulders as the tiger moves closer and closer to extinction. They have been unable to stop the flow of wildlife black-market trade and one day soon, this magnificent predator will vanish forever. The world must bring pressure to bear on all countries that use primitive medical remedies at the expense of a wild species

Leopard: Panthera pardus

The leopard is probably much better off than the tiger due to its survivability, size and tolerance to humans. Exact numbers are not known due to its very stealthy character but there are probably 1000 or more still living in the western part of Thailand all the way down to Malaysia. For some reason, they are not found in the East or the Northeast.

Leopard can survive on much smaller animals and will even take farmer’s cattle, pigs, dogs, cats and chickens. Their ability to blend in and being primarily nocturnal, one hardly ever sees them. Both color phases (yellow and black) are found and they are solitary except during breeding season. Their bones are also taken and the pelt is in demand. Leopards like the tiger are susceptible to poisoning of carcasses used by poachers.

In closing, only two things can save the Big Seven plus all the other animals and ecosystems they live in, and that is they must be protected from the onslaught that carries on day in and day out. Stories are popping up in the newspapers about poachers caught with guns and animal carcasses, and it seems to be a hot issue at the moment. These perpetrators need to be removed from local communities and sent to prison setting precedence so others will stay out of the protected areas.

Secondly, wildlife conservation education must be administered into all levels of society. Thailand’s wildlife and forests have evolved over millions of years and are far too important. Awareness, strict enforcement, better funding and management plus up-graded laws are the key!

Asian Elephants: Thailand’s Mega Fauna

Wild Species Report

A flagship species and cultural symbol

Thailand’s largest terrestrial animal on the brink of extinction

Wild elephant family unit in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Santuary

In 1927, a film was made depicting wild Thailand, and shown to audiences around the world. Entitled ‘Chang – A Drama of the Wilderness’, this epic documentary was produced by two American filmmakers Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, and released by Famous Players-Lasky, a division of Paramount Pictures.

‘Chang’ (Thai for elephant) is a melodrama and silent film about a man, the jungle, and wild animals as its cast. The main character is Kru, a poor farmer depicted in the film that battles tigers, leopards, bears and even rampaging elephants, all of which pose a constant threat to his livelihood. The saga was depicted in the northern province of Nan where thousands of wild elephants survived in vast herds at the time. The footage of elephants in the hundreds is remarkable.

Young tusker at a mineral lick in Huai Kha Khaeng

The film also shows tigers and leopards caught in pit-falls and dispatched with a muzzleloader from the top. It was an amazing piece of celluloid production where logistics must have been really tough. Chang was nominated for an Oscar for Unique and Artistic Production at the first Academy Awards in 1929. Cooper and Schoedsack went on to make the classic blockbuster movie King Kong.

Tusker in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

The Asian and African elephants are the only two surviving species of a once diverse and widespread group called proboscids (order Proboscidea), or animals with a trunk. They are characterized particularly by developments of their teeth and adaptation of their limbs for supporting their increasing mass. All total there is fossil evidence of some 350 species of ancestral proboscideans, mastodons, mammoths and modern elephants.

The first ancestor of elephants lived approximately 50 million years ago during the Late Eocene and Early Oligocene Epochs. It was named Moeritherium after the place where it was discovered, the Moeris Lake in Egypt. Though its form and appearance were completely different from the elephant, scientists base Moeritherium’s ancestry of the elephant on its skull and teeth. The skull had air holes, just like the elephant, and four small incisors grew from the upper and lower jaw that the growth of tusks had begun. At least three divergent groups of proboscideans evolved there from Moeritherium or close relatives.

Mature tusker camera trapped at a waterhole in Khao Ang Rue Nai

The next beast of elephantine build and bulk was the Deinotherium that was still not a true elephant. They became common in Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe during the Miocene Epoch. They were very large at 4 meters high with down curving tusks from the lower jaw. Surviving for 20 million years well into the Pleistocene Epoch, Deinotherium was clearly a very successful animal. About the same time Paleomastodon and Phiomia began to evolve and show the closet beginnings of a trunk allowing the species to feed higher off the ground.

Very old tuskless bull in Huai Kha Khaeng

At the beginning of the Miocene epoch about 24 million years ago, the ancestral Gomphotheres was the real commencement of Proboscidean diversity. There were literally hundreds of species at one point including mastodons and mammoths. Elephantidae is the family to which the modern elephant belongs and the first species was Elephas antiquus from the middle to late Pleistocene Epoch. However, by the beginning of the Holocene Epoch around 10,000 years ago, only two species remained: African elephants Loxodonta africana and Asian elephants Elephas maximus.

Tusker in Khao Ang Rue Nai

The main differences between the two species are anatomical. The African elephant are larger and has a more elongated skull, a trunk with deep rings, larger ears, a flat forehead and, in general, holds its head at a 45 – degree angel to the ground. Asian elephants are smaller and have a double – bulged forehead, a trunk with fewer rings, smaller ears and a skull with a 90 – degree orientation.

There are three Asian sub-species: the Sri Lankan elephant Elephas maximus maximus, the mainland elephant Elephas maximus indicus, and the Sumatran elephant Elephas maximus sumatranus, and two African sub-species: the bush elephant Loxodonta africana africana, and the forest elephant Loxodonta africana cyclotis.

Young tusker camera trapped at a waterhole in Huai Kah Khaeng

Prehistoric fossil evidence of proboscideans has been discovered in the north, the northeast, the central plains, and the south of Thailand. The first find in 1948 was fossil bones of Stegodon insignis (mastodon) during the construction of the bridge across the river just south of Nakorn Sawan provincial city. Following this, discoveries were made in lignite deposits in Lamphun, Lampang and Phayao provinces. Fossil teeth of a Deinotherium at Ban Sop Khan in Phayao have been uncovered. Another find new to science is the earliest known species Stegolophodon praelatidens fossils from the Early Miocene discovered in Lamphun and Lampang by Pascal Tassy (from France) and others.

Many extraordinary ancient proboscidean fossils have been unearthed in Nakhon Ratchasima (Korat) province at the Tha Chang and Chang Thong sand pits along the Mun River in Chaloem Prakiat district going back to the middle Miocene about 16 million years ago. Eight different genera of proboscideans have been discovered here and is a testimony to the Kingdom’s fossil record.

Family unit in Huai Kha Khaeng

About 150 years ago, wild elephants were surviving around Bangkok along the Chao Phraya River, and in the districts of Rangsit, Bang Sue, Bang Kapi and Bang Na. The ‘City of Angles’ was a real jungle back then. It seems difficult to believe but in those days, Thailand was almost completely covered by forest cover – more than 90 percent. Today, only 30 percent remains. Due to the immense destruction, elephants have been at the forefront of a disappearing habitat.

The best current estimates say there are no more than 2,500-3,000 elephants surviving in the wild of Thailand today. There are 60 protected areas that have less than a hundred elephants, and another eight protected areas that have over one hundred individuals as follows: Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary – 280-300; Khao Yai National Park – 200; Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary – 230; Salak Phra Wildlife Sanctuary – 175-200; Phu Luang Wildlife Sanctuary – 100; Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary – 135; Kui Buri National Park – 150 and Kaeng Krachan National Park – 115. Surely, an up-to-date consensus of the wild elephant population should be undertaken by the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP) in all the forests throughout the Kingdom, and a report published as soon as possible. As it stands, many of these quotes are mere guesstimates.

Young tusker on the road in Khao Yai National Park

Elephants have been persecuted for a long time. The following scenario has been chosen for this column and has been carried out for decades in Thailand’s forests, and unfortunately is the dark side of nature that carries on to this day. Gunshots reverberate explosively through the forest panicking and scattering a herd of wild elephants. The huge beasts instinctively flee as fast as they can through heavy foliage away from the cacophony. In minutes, the forest returns to normal but the sad fact is humans have just disrupted the herd permanently. A baby elephant mills aimlessly around its mother lying dead on the ground. The confused calf has no sense of danger as poachers move in and capture it to be sold on the illegal black market. The calf will likely be forced to wander city streets or work in tourist camps.

Such atrocities are still practiced by some unscrupulous people intent on killing the mother solely to capture the baby. Many other animals are also hunted down in much the same way like gibbons and monkeys. Middleman and end-use buyers perpetuate this market and seem to evade the law. Wildlife black-market trading is fueled by a few shady individuals and is on-going. Great strides have been achieved by a few wildlife enforcement agencies and many arrests have been made in recent years exposing these law-breaking individuals. However, the so-called ‘big fish’ continue to do business as usual. It is a never-ending battle!

Mature tusker on the road in Khao Yai

In another scenario, a mature bull elephant with a large set of tusks tramples and gores a man deep in a protected forest many days walk from the nearest village. News travels fast but is subdued by the authorities due to the sensitive nature of the incident. The man was with a group of poachers hunting the tusker and he was armed with a crude muzzleloader. He was separated from the group and came upon the huge herbivore firing a shot, which only enticed the old bull to charge. It was all over in seconds and when the man was found critically injured the group rushed him to the nearest medical facility but it was too late. The villagers cried fowl and hunted the old bull down eventually taking his tusks and selling them to a middleman for pennies compared to what they would fetch from a rich end-user or agent. This has been going on for ages to feed the illegal ivory trade.

Human settlement, agriculture and roads have taken over much of the elephant’s habitat. Villages spring up in old elephant terrain, and the trespassers expect the giants to simply fade away into the forest. But elephants can develop a taste for crops grown by farmers, and they often take what they want. Countless conflicts have arisen between villagers and the real owners of the land, whose ancestors have lived there for many thousands of years. Thailand is not alone to crop-raiding elephants. Other countries in Asia and Africa have experienced the same outcome when humans have taken over elephant land.

Very young tusker about five years old in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

Most of the conservation areas where wild elephants live are just small isolated pieces, and agricultural areas or towns surround these forests, a major obstruction to natural breeding. Elephants in each forest are caught on islands and cannot walk back and forth between these areas. Thus, inbreeding among close relatives is inevitable, which leads to an inferior population and causes genetic diseases, and ultimately, to extinction. Belinda Stewart-Cox with Elephant Conservation Network has campaigned relentlessly for the establishment of a corridor between Salakpra and Srinakarin protected areas in order to prevent the total isolation of Salakpra’s elephants. Other corridors in other parts of Thailand are on the drawing boards.

The young tusker a month earlier

Elephants have been maimed and killed by poisoning, pungee stakes and pit-falls, gunshots, and electrocution. They have been chased out of rice paddies, mango orchards, and pineapple and tapioca fields. The use of fireworks, bright lights and gunshots scare them away temporarily, but the elephants are intelligent enough to lose their fear of such ruses. Elephants grow bolder and go on the rampage, sometimes killing people, tearing up villages and damaging DNP facilities usually during the dry season when water is scarce.

Nick-named ‘Nong Saeng’ after the sanctuary

This year, a herd of wild elephants in a western national park raided a village and broke into a shack with fertilizer. A young calf gorged itself and died shortly thereafter. On the other side of the spectrum, an old tuskless bull killed a ranger in western Thailand, and a tusker gored a villager in the East. Wild elephants have also died or been injured accidently by vehicles speeding on roads in some protected areas. Most of the accidents occur at night when the elephants are difficult to see. Some conservation organizations have erected new signs in some areas warning drivers the danger of elephants on the road at night.

Mature tuskless bull in Kaeng Krachan National Park

These noble beasts have featured prominently in almost every important historical event in the Kingdom. They are national, royal, and religious icons of Thailand. The ‘white elephant’ was on the flag of Siam. They are a national symbol of pride and joy. The Thai elephant’s survival lies in the hands of those responsible for these vanishing Asian giants. Proactive conservation awareness is a top priority for the government and existing outdated laws (some a hundred years old) need to be reviewed and changed for the elephant’s future. Strict penalties and fines for poaching and encroachment need to be enforced to insure the survival of nature’s largest terrestrial mammal in Thailand before it is too late.

Ecology and behavior of elephants:

“Tractors of the forest” is what the late Mark Graham called wild elephants in his excellent book entitled ‘Thailand’s Vanishing Flora and Fauna’ co-authored by Philip Round, the eminent bird ornithologist. Graham went on to say “in all parts of Khao Yai National Park there are trails which have been used by herds of elephants for, in all probability, thousands of years”. This trait is evident throughout continental Thailand where these creatures roamed.

Tusker about 25 years old in Kaeng Krachan

Asian elephants consume 75-150 kilograms of food and about 80-160 liters of water per day. A variety of grass species including bamboo is consumed, as well as tender twigs, barks, leaves and fruit. Natural mineral deposits are also very important to these herbivores supplementing their diet. An adult mainland Asian elephant may reach a height of 3.5 meters and weigh 5,000 kilograms. Elephants form family units but lone bulls are common. Male elephants have tusks but tuskless bulls are now quite common and can be very bad tempered, especially if the bull is in a state known as ‘musth’ where fluid leaks from the temporal gland.

Mature tusker at a waterhole in Khao Ang Rue Nai

Reproduction of the Asian elephant is the same as the other sub-species. The young are born after a gestation period of 18-22 months. Elephants usually give birth to a single offspring, rarely twins, and more rarely triplets. A female elephant can give birth every 4-6 years, and has the potential of giving birth to seven offspring in her life. Life expectancy for elephants is 60-70 years.

Elephants in domestication:

Elephants are extremely intelligent creatures. For centuries, humans have taken elephants from the wild and turned them into many different uses such as war elephants, working elephants at logging sites, as pets, tourist attractions and street beggers.

Elephant on the highway in Ayuttaya province

My very close friend Richard Lair who works for the Forest Industry Organization at the Conservation Center in Lampang has worked with elephants for many years. He was the first to get elephants to paint in Thailand, and the first in the world to establish a musical band made up entirely of elephants. He has produced several CD’s of this accomplishment.

Begging elephant near the 700 year stadium in Chiang Mai

Probably the most appalling fate for a domesticated elephant is to become a ‘street walker’. These magnificent creatures are forced to saunter hot, dusty and polluted streets of Thai cities ‘begging’ for food and money. Stories about elephants hit by cars and falling into drainage ditches, plus other accidents have been documented. At one time, a trip at night around Bangkok and other cities in the Kingdom one was greeted by a huge gray beast with a red light and a flashing CD attached to its tail. Continuous calls for change went unnoticed by mahouts and the owners of these elephants who sneaked them into cities and tourist sites. Legislation concerning domesticated elephants remains old and out-dated, and law enforcement has also been very poor.

Domesticated elephants being trucked into Chiang Mai

In late-2010, I saw an elephant on the streets of Chiang Mai at night. I took a few photographs but just watched as the mahout and elephant went about their business of begging for money. However, the situation has improved and there are several new sanctuaries dedicated to helping both mahout and elephant. It seems that most of the elephants have left Bangkok but they are still found in the out-lying areas. Hopefully, one day, the street-walker will be a thing of the past and these magnificent creatures will be treated with the respect, love and admiration they deserve.

Elephant with handlers on the streets of Chiang Mai – An abstract