Sign Up or Log In

Gallery

Recent posts

- THAILAND’S NATURAL HERITAGE: A look at some of the rarest animals in the Kingdom – Part One

- WILDLIFE in THAILAND: A Photographic Portfolio of Thailand’s Natural Heritage – Part Three

- WILDLIFE in THAILAND: A Photographic Portfolio of Thailand’s Natural Heritage – Part Two

- WILDLIFE in THAILAND: A Photographic Portfolio of Thailand’s Natural Heritage – Part One

Archives

- May 2020

- April 2020

- November 2019

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- August 2017

- July 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- January 2017

- November 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- July 2009

Links

Wildlife Links

Posts Tagged ‘sambar’

Thailand’s mega-fauna caught on video

A Bushnell Trophy Cam set to video (IR capture at night) catches mega-fauna at night (wild elephant, gaur, banteng, sambar and Indochinese tiger) walking up a game trail in the heart of Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, a World Heritage Site situated in Western Thailand. Interestingly, a female tiger fitted with a radio collar is caught twice during the one month stint. All these animals are thriving very well in this amazing protected area, and is a tribute to Thailand’s natural heritage.

Sambar: Thailand’s largest Cervidae

WILD SPECIES REPORT: Majestic Asian deer and even-toed ungulate

Important prey species of the tiger and leopard

Sambar doe and yearling drinking from the Huai Kha Khaeng waterway

A mature sambar stag, Thailand’s largest deer with a heavy antler rack, barks a loud warning and stamps its front feet on the ground alerting all the denizens a predator is nearby. The pungent smell of a tiger floats through the forest, and animals within audible range are now on hi-alert. But the big cat is lightning fast and takes a young sambar doe from the herd that is perfect for a meal. Leaf monkeys squeal, squirrels chatter and birds call from the treetops. It is panic on the ground as the deer bolt in all directions.

But this is just the cycle of life that has gone for millions of years. One animal is sacrificed for the other to survive. Deer play a very important part in the prey-predator relationship for without them, the tiger would struggle to live and carry on its legacy as the largest cat in the world. Carnivores thrive if there are abundant prey animals to hunt.

Sambar yearling in Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary

Unfortunately in most parts of the country, the human being has eradicated sambar and other animal species like wild pig and common barking deer in man’s utter struggle to live. This has up-set the balance of nature. The big cats have also almost disappeared and as of a consequence, are now on the brink of extinction.

Wild animals and their ecosystems are under constant threat as the population expands further into the last vestiges of Thailand’s great natural heritage. At one time, the country was almost completely covered by vast expanses of virgin forests where sambar and other ungulates plus predators lived in complete harmony. That has all changed now and only a few large protected areas can boast that these big deer, or the tiger for that matter, still live in the interior.

Sambar stag after a mud bath in Huai Kha Khaeng

In any given forest, sambar was one of the first animals to disappear when man began cutting down forests to grow agriculture and build settlements. These deer were taken for meat, and their hides were shipped to Japan for ‘Samurai armor’ back before the turn of the 19th Century, and then for military equipment all the way up to just before World War Two. Literally millions of hides were exported and this had a serious effect on all the deer species.

It was a big business at the time and as an outcome, the other large cervids such as Schomburgk’s deer that has been globally extinct since the 1930s plus hog deer and Eld’s deer disappeared from the wild of Thailand. Sambar were more numerous and preferring deep forest, prevailed slightly better.

Sambar stag during the rut in Huai Kha Khaeng

Fossil evidence suggests that sambar evolved sometime during the Quaternary Period from large ungulates living on the huge plains of Asia at the time. The saber-toothed cat was one of the main carnivores that thrived on these hoofed animals.

My very first encounter with sambar was almost 15 years ago when I began photographing wildlife in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. Sambar was seen everyday crossing the river from Khao Ban Dai ranger station at the confluence of the Huai Kha Khaeng and Huai Mae Dee waterways. I was able to catch them on film fairly easily, especially at the mineral licks found by the river.

Sambar stag on the run in Huai Kha Khaeng

Some ten years ago, a large complex was built at Khao Ban Dai for VIPs including a huge visitor center plus three bungalows. Wildlife numbers dropped dramatically in the area due to the construction and the amount of labor numbering about 100 men and women that stayed on location for almost a year. Peafowl also disappeared.

Happily, the area around Khao Ban Dai has now begun to return to somewhat normal after observingthe chain of events and making regular visits to the station over the last few years. Sambar, wild pig, muntjac and green peafowl on occasion are seen on the sandbars during the early morning and late afternoon. Evidence of tigers and leopards from camera-traps now show these carnivores are roaming here once again but this is also probably due to its remoteness. Wildlife is making a slow comeback here.

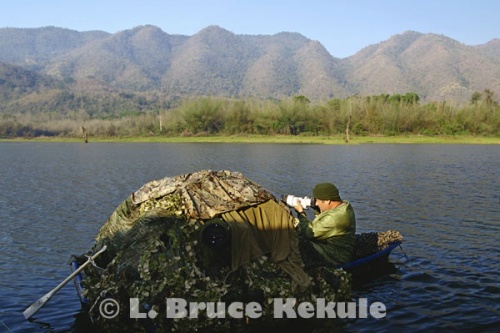

Huai Kha Khaeng – Huai Mae Dee junction

Down in the southern section of Huai Kha Khaeng however, sambar is still quite abundant. One frosty morning about 8am as I was sitting in my boat-blind waiting for wild water buffalo to come to the river, a sambar doe and several of her offspring popped out of the forest for refreshing drinks about four meters away. I had no other option than to take a head shot of them at the water’s edge as seen in the lead photograph. It was exciting to say the least and it took her a few moments to recognize the strange anomaly by the shoreline. She barked a warning at me and at that distance was extremely loud actually making me jump. The huge doe then crashed into the forest followed by the younger deer.

With increased protection, wild animals will survive as long as visitation by documentary film crews, scientific groups, nature lovers and tourists is kept reasonable or on a very limited scale. However, on many occasions large official and influential groups or research parties make their way into some of the very restricted protected areas and hold drinking sessions that carrying on into the wee hours of the morning while running the generator so ‘World Cup or soap operas’ can be watched on satellite TV.

Sambar yearling in Huai Kha Khaeng

Off-road groups still plow into some wildlife sanctuaries because the road conditions are the toughest in the country but these thrill-seekers who are usually connected, don’t care what damage they cause. The roads then become difficult to transverse created by their highly modified off-road vehicles that makes it doubly tough for the patrol rangers who have standard 4X4 trucks.

Over-visitation by the human element is like the plague as seen in many parks around the country with no limitation on vehicles and visitors with their ‘tent cities’ especially during the holidays. All of this of course is damaging but carries on for the prominent and connected, and surely has an affect disturbing the wildlife and ecosystem. A serious look into this behavior should be brought to the forefront. The term ‘double standard’ is also practiced in many reserves by some officials and will be difficult to stamp out.

Sambar stag in Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary

So with all this in mind, it should also be said that the situation on the ground with the forest rangers is still a long way from being good, and is definitely detrimental to good protection and enforcement. The age-old problem of the temporary rangers not receiving any pay for three to four months every year still exists. After visiting several protected areas in the east, west and south over the last few months, the first thing one hears is “no-pay” from October to late January and sometimes beyond due to a glitch in the system, or the so-called lack of a budget.

This phenomenon is not fully understood but it is basically against human rights when someone is employed and not paid especially around the New Year. People really need money at this time. In the last 15 years that I have worked and been around these rangers, it is still very disturbing that the ‘powers-to-be’ continue to overlook this very basic need. Some of these rangers then resort to beg, borrow and steal to survive. Many are in serious debt and struggle with moneylenders. Some commit wildlife crimes to get ahead.

Sambar herd, jungle fowl and crow in Khao Yai National Park

A close friend of mine who retired as chief from a large protected area in southwest Thailand set aside a special fund from his yearly budget to pay the rangers when the money did not arrive from the finance ministry. He also charged no interest when the money was paid back. These men had the highest esteem for this superintendent who really took care of his staff in times of need, and in turn these dedicated patrol rangers made a special effort to take care of this forest that actually flourished.

I know because I was on the ground then and caught many rare creatures like tiger, leopard, fishing cat, sun bear, banded linsang, banteng, gaur, Siamese crocodile plus many others on camera-trap and through the lens. It was truly an exciting experience seeing all these remarkable creatures living as Mother Nature intended.

Sambar doe and fawn in Huai Kha Khaeng

This system should be implemented by all the superintendants in the national parks and wildlife sanctuaries. Another option is to make all temporary hired rangers permanent staff so they at least they get paid on time for work rendered. But even permanent staff is now experiencing half payment. Under these circumstances how can anyone have incentive to go into the dangerous environment of the forest where poachers with guns shoot to kill? These men also have very poor insurance coverage.

It is hoped someone will take action to help these brave forest rangers that are probably the most important key to good protection and enforcement of Thailand’s natural heritage. For without them, sambar and all the other wonderful wild creatures in the Kingdom are in serious jeopardy. Pressure needs to be exerted from the Thai media so this draconian problem of ‘no pay for months’ on end will cease to exist.

Sambar doe in Sai Yok National Park

Sambar Ecology:

Sambar Cervus unicolor is a terrestrial mammal of the order Artiodactyla, or even-toed ungulate with two functional hoofed toes and two dew toes on each foot. These large deer have a four-chambered stomach and feed on plant material. Food is partially digested in the stomach and then brought back up into the mouth again for further chewing, to increase the amount of nutrition that can be obtained from grasses and leaves. As ruminants, this permits large amounts of food to be ingested quickly before moving to sheltered places for chewing, and better protection against predators.

Stags can weigh more than 500 kilograms and attain a height of 102 to 160 cm at the shoulder. They have long legs and can run at a fast pace to evade large carnivores. With their formidable antlers that can exceed a length of over a 100 cm, they are extremely dangerous to man when a male sambar has been wounded.

The coat is dark brown with chestnut marks on the rump and under parts. These cervids live primarily in woodland and feed on a variety of vegetation, including grasses, foliage, browse, fruit and water plants. Sambar is found in habitats ranging from tropical seasonal forests (dry forests and seasonal moist evergreen forests), subtropical mixed forests (conifers, broadleaf deciduous, and broadleaf evergreen tree species) to tropical rainforests.

They are seldom far from water and, although primarily of the tropics, are hardy and may range from sea level up to high elevations such as the pine and oak forests on the foothills of the Himalayan Mountains. They also live in montane mixed forests and grassland habitats at high elevations in the mountains of Northern Thailand.

Sambar needs serious protection to survive into the future. Good protective management with an increase in budget and personnel is needed. A true ranger training school with instructors from the National Parks department, Border Patrol Police, Special Forces, Navy Seals and an NGO like Freeland should be established somewhere in the central provinces away from any national park and all its distractions of over-visitation.

Also, it will provide easy access and distribution for new recruits who graduate as permanent rangers. Temporary rangers can also come and train, and then also become permanently employed. The day this happens will be a step in the right direction for wildlife conservation in the Kingdom.

Khao Yai: Thailand’s first and most famous national park

A World Heritage Site in the Northeast

Khao Yai – ‘The Big Mountain’

The concept of parks or wildlife sanctuaries in Siam dates back to the 13th century Sukhothai Period during the reign of King Ramkhamhaeng the Great who created a park known as ‘Dong Tan’ used for royal recreation and preservation. The people were also encouraged to set-up parks around Buddhist temples and other religious sites because it was against Buddhist strictures to take a life and hence all parks were havens of safety for the animals of the forests. However, from the end of the Sukhothai Period to the 19thCentury, parks and conservation declined.

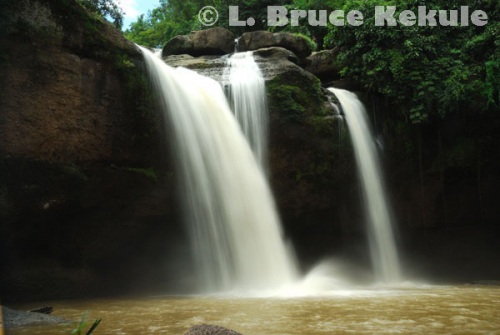

Haew Narok Waterfall in Khao Yai National Park

The Royal Forest Department (RFD) was established in 1896, introducing modern management practices to forestry, especially the teak industry. However, conservation fields were not addressed in the beginning. In 1900, the first law protecting animals was the Law Governing Conservation of Wild Elephants, and thus elephants became the first species protected by a law. In 1921, the law was amended, which superseded the previous act providing better protection.

Haew Suwat Waterfall in Khao Yai

Then in 1943, the RFD began turning its attention to conservation and efforts to manage certain forests for the public’s recreational use. The department established Phu Kradueng National Park in Loei province. However, due to World War II and very limited budgets and trained personnel, the park project was shelved.

Tusker in a mineral lick close to the road in Khao Yai

In 1959, Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat, Thailand’s prime minister, voiced his opinion about protecting some of the immense forests that existed in the Kingdom at the time. He made several inspection tours into the wild areas of the North and Northeast, and became impressed with the natural resources. His idea was to establish reserved areas much like Yellowstone National Park in the US and Kruger National Park in South Africa. His foresight has developed into one of the largest concentrations of protected areas in the world. At last count, there are more than 260 national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, non-hunting areas and marine national parks, plus 1,221 reserved forests situated throughout Thailand.

Tusker near the road

Sarit’s fascination with nature prompted him to establish the National Parks Committee and the Wild Animals Reservation and Protection Committee to hash out necessary protective management plans, and to select pristine wilderness areas suitable for preservation. The first new step to conserving wildlife was the enactment of the Wild Animals Reservation and Protection Act of 1960. The next law passed by legislation was the National Park Act of 1961, which really got the ball rolling. By Royal Decree, on September 18, 1962, the 2,165km2 Khao Yai National Park was appointed, becoming the nation’s first national park, thanks to Sarit and many others.

Muntjac munching on leaves by the road

The core group was made up of General Surajit Jarusaraenee, the Minister of Agriculture and General Prapas Jarusatien, who was the Minister of Interior, along with Chalerm Siriwan, the director general of the RFD and Pramual Unhanand, who was the director of the Bureau of Silviculture under the RFD. The first chief of the park was Boonlueng Saisorn. One man who was also involved in the establishment was Dr Boonsong Lekagul, who was the executive-director of the Association for the Conservation of Wildlife that was actually started up in 1951.

Muntjac male by the road in the park

Dr Boonsong, a well-to-do Thai medical physician, was also a hunter and biologist. He published scores of scientific papers and books on mammals, birds and butterflies found in Thailand. His enormous contribution to natural science was the first stepping-stone to knowledge of the natural world and a better understanding about Thai fauna. Dr Boonsong also collected wildlife specimens to document as many species as possible. He certainly made an impact on the movement of wildlife conservation.

Sambar stag in the campground

Dr George C. Ruhle, an American national park expert from the U.S. National Park Service did a survey in 1959-1960 and a report in 1964 for the ‘International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources’ (IUCN), and the American Committee for International Wildlife Protection’ about the forests. This work contributed to a greater understanding of Thailand’s natural heritage. He made many treks into the wilderness areas of Khao Yai, Thung Salaeng Luang and Doi Inthanon plus many others, and was instrumental in some of the first ‘national parks management plans’ that were to follow.

Banded Kingfisher by the campgrounds

After World War II, about 70 percent of the country was still covered in thick vegetation with an amazing array of wild animals and ecosystems. The first big area to be acknowledged was the primaeval contiguous forest once known as Dong Phaya Fai (or “Jungle of Fire”). This remarkable wilderness stretched from the lower Northeast all the way into Cambodia, and north to parts of the Central and north-Northeast regions. These mountain formations were created during continental uplift about 60 million years ago when the Indian Plate crashed into the Himalayas.

Pig-tailed macaque by the road

Kouprey, a rare wild cattle and now most likely extinct, lived in parts of this great forest. Large tigers preyed on abundant deer and other ungulate species that proliferated in the deep jungle. Smaller species, including clouded leopard, sun bear, gibbons, hornbills as well as many others were common. It was an impenetrable and dangerous place due to the steep mountainous terrain where no roads existed. Very few humans lived in the depths of this once great biosphere. Malaria and fierce creatures reigned supreme.

Great hornbill a its nest by the road

Before Khao Yai was formed, settlers and outlaws used slash-and-burn agriculture in the mountains, creating huge grasslands around the present-day headquarters area. Many of these people were evading the police, but they were evicted after the park was established. The government decided to establish a golf course on the grassland and bungalows to generate income, which was run by the Tourist Authority of Thailand (TAT). Back in the mid-1970s, I actually played golf on the links when it was opened to visitors. It was amazing seeing all those wild animals crossing the fairways. However, the “rough” was jungle, and if you did not hit the ball straight and true, it was a goner! It was a tough course to play on and I lost quite a few balls. It was, however, finally closed in 1991 at the urging of the Anand Panyarachun government.

Male muntjac jumping in front of a motorcycle at khao Khiew

In 1955, a road (Mittraphap Highway: Saraburi to Nakhon Ratchasima) was cut through the forest to facilitate the US military machine at the airbases in Nakhon Ratchasima, Udon Thani and Ubon Ratchathani provinces, as well as Phanom Sarakham district in Chachoengsao province in the Northeast. Later, another road separating Khao Yai and Thap Lan (Route 304: Kabin Buri to Pak Thong Chai) was constructed.

Muntjac jumping 2

These roads basically cut all migration routes of elephant, gaur, banteng and other large mammals established over thousands of years, and opened up virgin forest to settlement. In the meantime, Khao Yai was being encroached on from all sides and can be seen today as resorts, golf courses and agriculture that completely surrounded the park.

Muntjac jumping 3

Khao Yai (“Big Mountain” in English) is part of the Dong Phaya Yen-Khao Yai forest complex covering 6,152km2, and is also Thailand’s second World Heritage Site, which was granted on July 14, 2005 by Unesco. The complex is comprised of five protected areas – Khao Yai, Thap Lan (1981, 2,235km2), Pang Sida (1982, 844km2) and Ta Phraya (1996, 594km2) national parks, and Dong Yai Wildlife Sanctuary (1996, 312km2).

Tusker and tourist bus on the road – a dangerous situation

Khao Yai is Thailand’s third largest national park and covers four provinces including Saraburi, Nakhon Nayok, Prachin Buri and Nakhon Ratchasima (Khorat). It incorporates parts of the Sankampaeng range made up of shale and sandstone at the south-east edge of the Khorat Plateau. The highest peak is Khao Rom at 1,365m and vegetation includes moist evergreen, dry evergreen, hill evergreen, mixed deciduous, dry dipterocarp, secondary forest and grassland. Some formations in the park go back more than 100 million years when dinosaurs roamed here. One set of dinosaur footprints has been found in Khao Yai on an isolated slab of red sandstone by the banks of the Sai Yai River. Some dinosaur fossils have been found close by in Thap Lan and Pang Sida national parks to the east.

Tusker on the road in the late afternoon

Today, elephants, gaur, sambar and muntjac (common barking deer) are still common, but unfortunately, only survive around the Khao Yai headquarters area for about 300km2. Years and years of degradation and poaching have taken its toll imploding towards the centre. Very few animals or birds survive in the outlying areas after many wildlife surveys done by various organisations and individuals came up with data to confirm the void. Even though Khao Yai was the first national park, it certainly has been devastated by years of minimal protective management and prolonged encroachment and poaching.

Tusker charging my truck – reverse was the only option

However, much research, training and management planning has been carried out in Khao Yai, primarily around the headquarters area. One of the first people in 1975 was Dr Chumphon Ngampongsai, who studied habitat relation of the sambar. Secondly, Dr Warren Brockelman of the US and some of his students from Mahidol University have conducted what is now the longest primate study in the world at “Mo Singto Forest Dynamics Plot” of the intricate lives and habitats of both white-handed and pileated gibbons that live together and sometimes produce a hybrid of the two species.

Philip D. Round and George Gale also carried out a bird survey in the plot. In 1978, a hornbill ecology research team under Dr Pilai Poonswad began hornbill surveys and helped increase nest sites. In the 1980s, Dr Surachet Chettamas from Kasetsart University wrote a Khao Yai park and recreation management plan, and Robert Dobias from the US also did planning at that time.

In the late-1990s, a master student, Sean C. Austin from New Mexico State University, did a survey for sympatric carnivores such as the leopard cat, clouded leopard, Asian wild dog and binturong, as well as radio-collared quite a few of them. He also used camera trap technology to build up a database.

In 1999, “Wild Aid”, now known as “Freeland”, started the Khao Yai Conservation Project including community outreach, wildlife monitoring, ranger training and park management in partnership with the Department of National Parks, and the Wildlife Conservation Society who did camera trapping and managed to catch a few tigers on film plus a multitude of other creatures.

Wild Aid also set up a team to monitor the park’s wild elephants and provided some equipment to the rangers. Another master student, Kate Jenks, from the Smithsonian Institute carried out a camera trap programme that involved an attempt to photograph carnivores in conjunction with Wild Aid from 2004 to 2007. Sadly, she camera trapped no tigers during the program but did record one set of tiger footprints in 2005.

Dr Naris Bhumpakphan of Kasetsart University sent master student Preecha Prommakul to monitor and camera-trap tigers in Khao Yai, but with a lack of data, the program was shelved. Preecha did, however, see a set of tracks around the back of a camera trap, indicating a tiger was possibly avoiding the traps.

Unfortunately, it looks as though the tiger has probably disappeared from the park. These magnificent cats have not been seen or recorded for some time now and no camera trap photos have been collected of tigers since 2001. However, reports of sightings and tracks do come in from time to time, but these are now rare. If leopards once thrived here, it was a long time ago.

Asian wild dogs are now at the top of the food chain. A large pack of more than 20 dogs devouring a sambar in one hour has been observed by a tour guide and the rangers. These pack animals are ferocious carnivores and once a feeding frenzy has begun, it’s every dog for itself. They have been consistently seen and photographed around the headquarters area.

Khao Yai is one of the best places to see wild elephants up close during the day or night. These giants can be seen along the road down to Nakhon Nayok, but from the safety of one’s motor vehicle. They also can be seen at the mineral licks set up on the grasslands. It is definitely recommended not to exit your car and strike out on foot as the elephants can become irritated and things could get dangerous, especially an encounter with a bull in musth, or a mother with a baby. Bull elephants in the park have killed several Buddhist monks in the forest meditating.

A birdwatcher friend of mine took his family out one night and was surrounded by a herd of elephants on the road. These gentle giants dented his van, costing him thousands of baht in repairs, and scaring the heck out of them while they sat motionlessly waiting for the herd to pass.

The most famous waterfalls in Khao Yai are Haew Narok, which takes a hike of about one kilometre and Haew Suwat, not far from the road. During the rainy season all of the rivers in the park become raging torrents. Quite a few elephants have been washed over the falls at Haew Narok and killed during heavy rain with swollen rivers. A temporary ranger station has been set up to ward off any elephants trying to cross during a heavy surge. There are more than a dozen marked nature trails covering about 50km for the adventurous type, but it is advised to hire a guide from the park as some are ever-changing and one could get lost in the dense forests.

During the rainy season, leeches and malaria mosquitoes are a problem. During the dry season, ticks can be irritating and dangerous to one’s health as some carry diseases. Insect repellent, leech socks and heavy clothing are the best way to ward off the bothersome creatures. But seeing the exotic mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians, butterflies and other insects in their natural habitats, plus the beautiful flora is still quite good and worth the effort.

The best time to visit is during midweek. Make your bookings in advance with the department’s online website for accommodations. Food and services are good but close shop at around 6pm. One of the biggest problems facing Khao Yai is the over-abundance of visitors during the holidays and long weekends, plus excessive spotlighting during these times. There is quite a large number of buildings, bungalows and campsites, and rubbish can be a problem for the park.

Many deer and other animals have perished from foam and plastic intact by eating discarded food containers. Khao Yai as Thailand’s first national park should be a role model for all other conservation areas. Given this important heritage, increased efforts by those responsible need to be made to save this magnificent biosphere. It is a fact that, with good protection, animals and plants will make a comeback. The park has the potential and we the people need to ensure its future survival.

Huai Kha Khaeng – A sanctuary of beauty and World Heritage Site..!

THIS POST IS THE FOURTH IN A SERIES OF WILDLIFE STORIES THAT WERE PUBLISHED IN THE BANGKOK POST. Text and photos © L. Bruce Kekule

A sanctuary of beauty: Thailand’s top protected area in the central-west

Wild water buffalo herd in Huai Kha Khaeng

Mist hangs in the air early one morning as a green peafowl calls from up-river. A male bird, its long tail feathers glistening in the early sun, struts across a sandbar looking for something to eat. A pair of wreathed hornbills fly into a fruiting fig tree and two white-winged ducks honk as they wing past Khao Ban Dai ranger station deep in the interior of Thailand’s top protected area.

Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, which covers some 2,780 square kilometers (1,073 square miles) of mountainous forest in Uthai Thani province in the western central plains, is one of the greatest biospheres on the planet. Its status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site is well deserved. The river named Huai Kha Khaeng flows through the middle of the sanctuary for about 100 kilometers before joining the Khwae Yai River further south. This riverine habitat has an unmatched biodiversity with many tributary streams that course through hilly woodland. Thousands of plants and animals thrive here, and the sanctuary is truly a tribute to the Kingdom’s natural heritage.

Tuskless bull elephant at a mineral deposit

Deciduous and hill evergreen forest make up most of this forest. Thousands of insect species thrive and the bird life is exceptional. There are an incredible 22 woodpecker species including the white-bellied and great slaty, the largest of the “Old World” woodpeckers – one of the highest densities in the world for comparable areas. Hornbills and fish-eagles are also found along the river, and all up there are more than 350 recorded bird species.

Banteng cows at a waterhole

Thailand’s largest bird, the green peafowl is now rare and found only in a few locations in the Kingdom. It is the most spectacular of all Thai birds, especially in November when the breeding season begins. The magnificent tail feather display when the male walks along the river is really something to see. The call of a male peafowl is truly inspirational, and its feathers a beautiful translucent green color. These birds still thrive in the deciduous and bamboo thickets along the river and in the interior, and this sanctuary has the one of the last and largest wild concentration of this species in the world.

Banteng bull by Huai Mae Dee, a tributary of Huai Kha Khaeng

Mammals from elephants to treeshrews survive in good numbers in most areas of the sanctuary. Due to an incredible amount of prey animals like deer, wild pig and cattle, the tiger, leopard and Asian wild dog thrive in good numbers too. There are eight species of cat from the tiger down to the little leopard cat, plus another eight species of civet. Three species of wild bovid including gaur, banteng and wild water buffalo are here, probably the only place in the world where this occurs.

Banteng herd including a big bull, cows and calves

Probably, the most significant species in the protected area is the buffalo. This is the last wild herd in the Kingdom, and Southeast Asia for that matter. Centuries ago, wild water buffalo were found in many forests and rivers. A mature bull can weigh up to a ton and have hooves eight inches (20cm) across. They leave deep tracks in the sandy soil along the river. These magnificent bovid are much larger and more aggressive than their domestic counterparts. Wild buffalo have a distinct forehead with horn bases closer together than domestic buffalo, whose boss is wider. Wild buffalo have a fierce temperament and will group together in the herd to face a predator like a tiger or Asian wild dog. Male solitary bulls will charge without hesitation. Many a hunter has had a close call or been killed by these massive low-slung beasts.

Wild water buffalo cow charging my boat-blind

Due to a very small population of just 50 or so individuals, the future of the wild water buffalo in Thailand is uncertain. Many dangers threaten them, such as foot and mouth disease, which could easily be passed on by domesticated buffalo living just outside the southern border of the sanctuary. In the past, local villagers have deliberately mingled their buffalo with the wild herd so that the offspring would be sturdy. Also, a few solitary bulls have come out of the sanctuary looking for females in heat. This is a very dangerous situation, which if not checked, could lead to a decline of all the classic herbivores in Huai Kha Khaeng. The southern border at Krueng Krai ranger station remains a gateway for danger and must be protected at all costs.

Black leopard in the afternoon sun showing its spots

Carnivores such as tiger and leopard are common in the interior, as are the herbivores. The balance of nature is played out everyday where “eat or be eaten” is the norm. Vultures were once found here but have virtually disappeared from Thailand’s skies primarily due to people poisoning carcasses. Illegal poaching, logging and gathering of forest products still occurs on a small scale and is a constant drain on all the species of flora and fauna.

Indochinese tiger at a waterhole deep in the interior

Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary is part of the ‘Western Forest Complex’, the largest forested area in Southeast Asia, which covers some 15,000 square kilometers (5800 sq. miles). All the protected areas are the responsibility of the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation. Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary to the west is also a World Heritage Site and forms a continuous forest with Huai Kha Khaeng.

Seub Nakhasathien – Thailand’s hero of wildlife conservation

There are many heroes of the past but one-man – Seub Nakhasathien – stands out. Seub gave his life for Huai Kha Khaeng and the nature conservation movement. In September 1990, this dedicated ranger, who fought hard for the rights of wild flora and fauna, took his own life at the headquarters area. A large bronze statue has been built close to his house in his honor, and is now his spiritual home. Many people flock to this magic place, including myself, to pay homage to him.

Oriental darter drying its wings in the morning sun

Seub helped to propose Huai Kha Khaeng as a World Heritage Site, along with Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary to the west. But he did not live long enough to see the proposal accepted. Together, the two sanctuaries help protect 6,427 square kilometers (2,481 square miles) of pristine wildlife habitat. They make up one of the finest and largest protected areas in Southeast Asia. The flora and fauna of this area includes an exceptional number of species from four bio-geographic zones – Sino-Himalayan, Sundaic, Indo-Burmese and Indo-Chinese, with significant habitat diversity.

The author in an old boat-blind after wild water buffalo

Four or five years ago, the department built a huge visitor center and three VIP bungalows at Khao Ban Dai. More than one hundred construction workers camped out here and materials were trucked into the location. Construction took more than a year. During and just after the completion of these buildings, I made many trips to the station only to find out that green peafowl and many other creatures normally seen had disappeared, or it seemed that way. Last month, I made a trip to Khao Ban Dai and it was an inspiration to see that green peafowl, wreathed hornbills, fish-eagles, banteng, gaur have returned to this magnificent natural paradise. It means, increase protection and patrols by the DNP are really working over the long run.

However, the importance of saving Huai Kha Khaeng for future generations cannot be stressed enough. It is hoped that management of the protected area will continue to improve, and government funding will also increase. More personnel are needed to take care of these valuable places. As it stands, budgets have been consistently slashed across the board for all protected areas over the last few years by bean counters. The department’s old policies need to be improved, and a constant watch kept for corruption – it can be tough to prevent. Only time will tell if Huai Kha Khaeng can survive such threats.

NOTES FROM THE FIELD:

In December 2008 when the first cold snap arrives, I was fortunate to visit Huai Kha Khaeng for a week or so. The dry season had begun and dead leaves carpeted the forest floor. Along Huai Mae Dee, the largest tributary of Huai Kha Khaeng, several wildlife-viewing platforms have been erected allowing rangers and researchers to do surveys, and wildlife photographers a chance to photograph the magnificent wildlife thriving here including elephant, banteng, gaur, sambar, muntjac, and very occasionally a tiger or leopard. Other creatures like macaque monkeys, green peafowl, yellow-throated martin and many other smaller animals are also seen here.

Tuskless bull elephant in the afternoon sun

On the morning of Christmas Eve, I awoke early, ate breakfast and drove some 8 kilometers to the trail leading down to the photo-blind. As I walked down the trail about 6am, I came upon a large pile of fresh elephant dung that had just been deposited. A large solitary bull elephant was close by. I hesitated, but carried on feeling lucky that I would not bump into him. I reached the blind and began climbing up the ladder when a rung gave way and I fell through. When the smoke cleared, I had broken two ribs. I then picked up my cameras and other equipment and managed to climb up crossing over where the third rung had been.

I then settled in the blind with my cameras facing across the river at the mineral deposit (commonly called salt lick). Many creatures come to these natural seeps for the life giving minerals. After waiting all day in pain, at about 4:30pm, a large tusk-less bull elephant stepped out of the forest in beautiful afternoon light and crossed the river just 20 meters from where I was. He then headed down river and I gave out a sigh of relief. Loners like this old boy (estimated about 40 years old) are sometimes very aggressive to anything it senses as a threat. It has become difficult to get good photographs due to their elusive nature. Our paths crossed very briefly and I feel privileged to have seen and photographed this magnificent wild elephant.

New addition to the above that was not published with the original story due to space in the newspaper…Update: 18 July, 2017….!

However, I was not doing too good. I had to leave all my stuff as I could not carry anything back for an hour’s walk to the truck with the worrisome rib bones that hurt like hell.

The next day, I tried to sit in another blind closer to the road but that was really tough. I finally got back to my truck and drove to Bangkok where I was omitted to the hospital with two broken ribs. It put me out of action for quite awhile as it is tough moving around with said ribs and one must strap-up with large belly-band belts, all day and all night for quite a while (over one year for me) to heal…it was a very slow process and after two years, I feel OK…but every once in awhile, I get a twinge in the small of my back where the break took place……!

Published in the Bangkok Post’s Outlook Section on April 27, 2009. Most of the photos shown above were actually used in the newspaper article when it was published.