Sign Up or Log In

Gallery

Recent posts

- THAILAND’S NATURAL HERITAGE: A look at some of the rarest animals in the Kingdom – Part One

- WILDLIFE in THAILAND: A Photographic Portfolio of Thailand’s Natural Heritage – Part Three

- WILDLIFE in THAILAND: A Photographic Portfolio of Thailand’s Natural Heritage – Part Two

- WILDLIFE in THAILAND: A Photographic Portfolio of Thailand’s Natural Heritage – Part One

Archives

- May 2020

- April 2020

- November 2019

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- August 2017

- July 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- January 2017

- November 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- July 2009

Links

Wildlife Links

Posts Tagged ‘kouprey’

Khao Yai: Thailand’s first and most famous national park

A World Heritage Site in the Northeast

Khao Yai – ‘The Big Mountain’

The concept of parks or wildlife sanctuaries in Siam dates back to the 13th century Sukhothai Period during the reign of King Ramkhamhaeng the Great who created a park known as ‘Dong Tan’ used for royal recreation and preservation. The people were also encouraged to set-up parks around Buddhist temples and other religious sites because it was against Buddhist strictures to take a life and hence all parks were havens of safety for the animals of the forests. However, from the end of the Sukhothai Period to the 19thCentury, parks and conservation declined.

Haew Narok Waterfall in Khao Yai National Park

The Royal Forest Department (RFD) was established in 1896, introducing modern management practices to forestry, especially the teak industry. However, conservation fields were not addressed in the beginning. In 1900, the first law protecting animals was the Law Governing Conservation of Wild Elephants, and thus elephants became the first species protected by a law. In 1921, the law was amended, which superseded the previous act providing better protection.

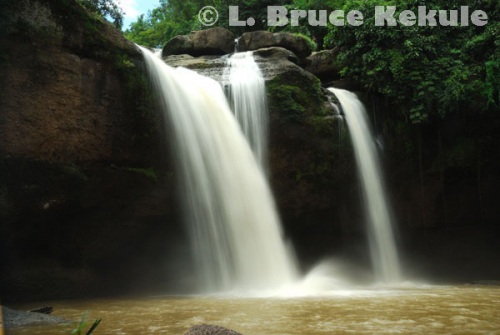

Haew Suwat Waterfall in Khao Yai

Then in 1943, the RFD began turning its attention to conservation and efforts to manage certain forests for the public’s recreational use. The department established Phu Kradueng National Park in Loei province. However, due to World War II and very limited budgets and trained personnel, the park project was shelved.

Tusker in a mineral lick close to the road in Khao Yai

In 1959, Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat, Thailand’s prime minister, voiced his opinion about protecting some of the immense forests that existed in the Kingdom at the time. He made several inspection tours into the wild areas of the North and Northeast, and became impressed with the natural resources. His idea was to establish reserved areas much like Yellowstone National Park in the US and Kruger National Park in South Africa. His foresight has developed into one of the largest concentrations of protected areas in the world. At last count, there are more than 260 national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, non-hunting areas and marine national parks, plus 1,221 reserved forests situated throughout Thailand.

Tusker near the road

Sarit’s fascination with nature prompted him to establish the National Parks Committee and the Wild Animals Reservation and Protection Committee to hash out necessary protective management plans, and to select pristine wilderness areas suitable for preservation. The first new step to conserving wildlife was the enactment of the Wild Animals Reservation and Protection Act of 1960. The next law passed by legislation was the National Park Act of 1961, which really got the ball rolling. By Royal Decree, on September 18, 1962, the 2,165km2 Khao Yai National Park was appointed, becoming the nation’s first national park, thanks to Sarit and many others.

Muntjac munching on leaves by the road

The core group was made up of General Surajit Jarusaraenee, the Minister of Agriculture and General Prapas Jarusatien, who was the Minister of Interior, along with Chalerm Siriwan, the director general of the RFD and Pramual Unhanand, who was the director of the Bureau of Silviculture under the RFD. The first chief of the park was Boonlueng Saisorn. One man who was also involved in the establishment was Dr Boonsong Lekagul, who was the executive-director of the Association for the Conservation of Wildlife that was actually started up in 1951.

Muntjac male by the road in the park

Dr Boonsong, a well-to-do Thai medical physician, was also a hunter and biologist. He published scores of scientific papers and books on mammals, birds and butterflies found in Thailand. His enormous contribution to natural science was the first stepping-stone to knowledge of the natural world and a better understanding about Thai fauna. Dr Boonsong also collected wildlife specimens to document as many species as possible. He certainly made an impact on the movement of wildlife conservation.

Sambar stag in the campground

Dr George C. Ruhle, an American national park expert from the U.S. National Park Service did a survey in 1959-1960 and a report in 1964 for the ‘International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources’ (IUCN), and the American Committee for International Wildlife Protection’ about the forests. This work contributed to a greater understanding of Thailand’s natural heritage. He made many treks into the wilderness areas of Khao Yai, Thung Salaeng Luang and Doi Inthanon plus many others, and was instrumental in some of the first ‘national parks management plans’ that were to follow.

Banded Kingfisher by the campgrounds

After World War II, about 70 percent of the country was still covered in thick vegetation with an amazing array of wild animals and ecosystems. The first big area to be acknowledged was the primaeval contiguous forest once known as Dong Phaya Fai (or “Jungle of Fire”). This remarkable wilderness stretched from the lower Northeast all the way into Cambodia, and north to parts of the Central and north-Northeast regions. These mountain formations were created during continental uplift about 60 million years ago when the Indian Plate crashed into the Himalayas.

Pig-tailed macaque by the road

Kouprey, a rare wild cattle and now most likely extinct, lived in parts of this great forest. Large tigers preyed on abundant deer and other ungulate species that proliferated in the deep jungle. Smaller species, including clouded leopard, sun bear, gibbons, hornbills as well as many others were common. It was an impenetrable and dangerous place due to the steep mountainous terrain where no roads existed. Very few humans lived in the depths of this once great biosphere. Malaria and fierce creatures reigned supreme.

Great hornbill a its nest by the road

Before Khao Yai was formed, settlers and outlaws used slash-and-burn agriculture in the mountains, creating huge grasslands around the present-day headquarters area. Many of these people were evading the police, but they were evicted after the park was established. The government decided to establish a golf course on the grassland and bungalows to generate income, which was run by the Tourist Authority of Thailand (TAT). Back in the mid-1970s, I actually played golf on the links when it was opened to visitors. It was amazing seeing all those wild animals crossing the fairways. However, the “rough” was jungle, and if you did not hit the ball straight and true, it was a goner! It was a tough course to play on and I lost quite a few balls. It was, however, finally closed in 1991 at the urging of the Anand Panyarachun government.

Male muntjac jumping in front of a motorcycle at khao Khiew

In 1955, a road (Mittraphap Highway: Saraburi to Nakhon Ratchasima) was cut through the forest to facilitate the US military machine at the airbases in Nakhon Ratchasima, Udon Thani and Ubon Ratchathani provinces, as well as Phanom Sarakham district in Chachoengsao province in the Northeast. Later, another road separating Khao Yai and Thap Lan (Route 304: Kabin Buri to Pak Thong Chai) was constructed.

Muntjac jumping 2

These roads basically cut all migration routes of elephant, gaur, banteng and other large mammals established over thousands of years, and opened up virgin forest to settlement. In the meantime, Khao Yai was being encroached on from all sides and can be seen today as resorts, golf courses and agriculture that completely surrounded the park.

Muntjac jumping 3

Khao Yai (“Big Mountain” in English) is part of the Dong Phaya Yen-Khao Yai forest complex covering 6,152km2, and is also Thailand’s second World Heritage Site, which was granted on July 14, 2005 by Unesco. The complex is comprised of five protected areas – Khao Yai, Thap Lan (1981, 2,235km2), Pang Sida (1982, 844km2) and Ta Phraya (1996, 594km2) national parks, and Dong Yai Wildlife Sanctuary (1996, 312km2).

Tusker and tourist bus on the road – a dangerous situation

Khao Yai is Thailand’s third largest national park and covers four provinces including Saraburi, Nakhon Nayok, Prachin Buri and Nakhon Ratchasima (Khorat). It incorporates parts of the Sankampaeng range made up of shale and sandstone at the south-east edge of the Khorat Plateau. The highest peak is Khao Rom at 1,365m and vegetation includes moist evergreen, dry evergreen, hill evergreen, mixed deciduous, dry dipterocarp, secondary forest and grassland. Some formations in the park go back more than 100 million years when dinosaurs roamed here. One set of dinosaur footprints has been found in Khao Yai on an isolated slab of red sandstone by the banks of the Sai Yai River. Some dinosaur fossils have been found close by in Thap Lan and Pang Sida national parks to the east.

Tusker on the road in the late afternoon

Today, elephants, gaur, sambar and muntjac (common barking deer) are still common, but unfortunately, only survive around the Khao Yai headquarters area for about 300km2. Years and years of degradation and poaching have taken its toll imploding towards the centre. Very few animals or birds survive in the outlying areas after many wildlife surveys done by various organisations and individuals came up with data to confirm the void. Even though Khao Yai was the first national park, it certainly has been devastated by years of minimal protective management and prolonged encroachment and poaching.

Tusker charging my truck – reverse was the only option

However, much research, training and management planning has been carried out in Khao Yai, primarily around the headquarters area. One of the first people in 1975 was Dr Chumphon Ngampongsai, who studied habitat relation of the sambar. Secondly, Dr Warren Brockelman of the US and some of his students from Mahidol University have conducted what is now the longest primate study in the world at “Mo Singto Forest Dynamics Plot” of the intricate lives and habitats of both white-handed and pileated gibbons that live together and sometimes produce a hybrid of the two species.

Philip D. Round and George Gale also carried out a bird survey in the plot. In 1978, a hornbill ecology research team under Dr Pilai Poonswad began hornbill surveys and helped increase nest sites. In the 1980s, Dr Surachet Chettamas from Kasetsart University wrote a Khao Yai park and recreation management plan, and Robert Dobias from the US also did planning at that time.

In the late-1990s, a master student, Sean C. Austin from New Mexico State University, did a survey for sympatric carnivores such as the leopard cat, clouded leopard, Asian wild dog and binturong, as well as radio-collared quite a few of them. He also used camera trap technology to build up a database.

In 1999, “Wild Aid”, now known as “Freeland”, started the Khao Yai Conservation Project including community outreach, wildlife monitoring, ranger training and park management in partnership with the Department of National Parks, and the Wildlife Conservation Society who did camera trapping and managed to catch a few tigers on film plus a multitude of other creatures.

Wild Aid also set up a team to monitor the park’s wild elephants and provided some equipment to the rangers. Another master student, Kate Jenks, from the Smithsonian Institute carried out a camera trap programme that involved an attempt to photograph carnivores in conjunction with Wild Aid from 2004 to 2007. Sadly, she camera trapped no tigers during the program but did record one set of tiger footprints in 2005.

Dr Naris Bhumpakphan of Kasetsart University sent master student Preecha Prommakul to monitor and camera-trap tigers in Khao Yai, but with a lack of data, the program was shelved. Preecha did, however, see a set of tracks around the back of a camera trap, indicating a tiger was possibly avoiding the traps.

Unfortunately, it looks as though the tiger has probably disappeared from the park. These magnificent cats have not been seen or recorded for some time now and no camera trap photos have been collected of tigers since 2001. However, reports of sightings and tracks do come in from time to time, but these are now rare. If leopards once thrived here, it was a long time ago.

Asian wild dogs are now at the top of the food chain. A large pack of more than 20 dogs devouring a sambar in one hour has been observed by a tour guide and the rangers. These pack animals are ferocious carnivores and once a feeding frenzy has begun, it’s every dog for itself. They have been consistently seen and photographed around the headquarters area.

Khao Yai is one of the best places to see wild elephants up close during the day or night. These giants can be seen along the road down to Nakhon Nayok, but from the safety of one’s motor vehicle. They also can be seen at the mineral licks set up on the grasslands. It is definitely recommended not to exit your car and strike out on foot as the elephants can become irritated and things could get dangerous, especially an encounter with a bull in musth, or a mother with a baby. Bull elephants in the park have killed several Buddhist monks in the forest meditating.

A birdwatcher friend of mine took his family out one night and was surrounded by a herd of elephants on the road. These gentle giants dented his van, costing him thousands of baht in repairs, and scaring the heck out of them while they sat motionlessly waiting for the herd to pass.

The most famous waterfalls in Khao Yai are Haew Narok, which takes a hike of about one kilometre and Haew Suwat, not far from the road. During the rainy season all of the rivers in the park become raging torrents. Quite a few elephants have been washed over the falls at Haew Narok and killed during heavy rain with swollen rivers. A temporary ranger station has been set up to ward off any elephants trying to cross during a heavy surge. There are more than a dozen marked nature trails covering about 50km for the adventurous type, but it is advised to hire a guide from the park as some are ever-changing and one could get lost in the dense forests.

During the rainy season, leeches and malaria mosquitoes are a problem. During the dry season, ticks can be irritating and dangerous to one’s health as some carry diseases. Insect repellent, leech socks and heavy clothing are the best way to ward off the bothersome creatures. But seeing the exotic mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians, butterflies and other insects in their natural habitats, plus the beautiful flora is still quite good and worth the effort.

The best time to visit is during midweek. Make your bookings in advance with the department’s online website for accommodations. Food and services are good but close shop at around 6pm. One of the biggest problems facing Khao Yai is the over-abundance of visitors during the holidays and long weekends, plus excessive spotlighting during these times. There is quite a large number of buildings, bungalows and campsites, and rubbish can be a problem for the park.

Many deer and other animals have perished from foam and plastic intact by eating discarded food containers. Khao Yai as Thailand’s first national park should be a role model for all other conservation areas. Given this important heritage, increased efforts by those responsible need to be made to save this magnificent biosphere. It is a fact that, with good protection, animals and plants will make a comeback. The park has the potential and we the people need to ensure its future survival.