Posts Tagged ‘elephant’

Asian Elephants: Thailand’s Mega Fauna

Wild Species Report

A flagship species and cultural symbol

Thailand’s largest terrestrial animal on the brink of extinction

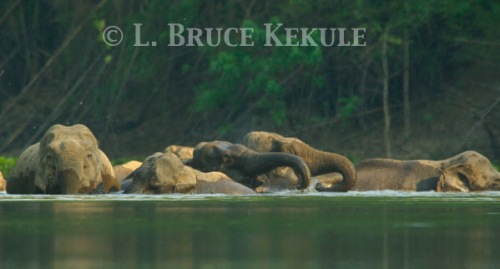

Wild elephant family unit in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Santuary

In 1927, a film was made depicting wild Thailand, and shown to audiences around the world. Entitled ‘Chang – A Drama of the Wilderness’, this epic documentary was produced by two American filmmakers Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, and released by Famous Players-Lasky, a division of Paramount Pictures.

‘Chang’ (Thai for elephant) is a melodrama and silent film about a man, the jungle, and wild animals as its cast. The main character is Kru, a poor farmer depicted in the film that battles tigers, leopards, bears and even rampaging elephants, all of which pose a constant threat to his livelihood. The saga was depicted in the northern province of Nan where thousands of wild elephants survived in vast herds at the time. The footage of elephants in the hundreds is remarkable.

Young tusker at a mineral lick in Huai Kha Khaeng

The film also shows tigers and leopards caught in pit-falls and dispatched with a muzzleloader from the top. It was an amazing piece of celluloid production where logistics must have been really tough. Chang was nominated for an Oscar for Unique and Artistic Production at the first Academy Awards in 1929. Cooper and Schoedsack went on to make the classic blockbuster movie King Kong.

Tusker in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

The Asian and African elephants are the only two surviving species of a once diverse and widespread group called proboscids (order Proboscidea), or animals with a trunk. They are characterized particularly by developments of their teeth and adaptation of their limbs for supporting their increasing mass. All total there is fossil evidence of some 350 species of ancestral proboscideans, mastodons, mammoths and modern elephants.

The first ancestor of elephants lived approximately 50 million years ago during the Late Eocene and Early Oligocene Epochs. It was named Moeritherium after the place where it was discovered, the Moeris Lake in Egypt. Though its form and appearance were completely different from the elephant, scientists base Moeritherium’s ancestry of the elephant on its skull and teeth. The skull had air holes, just like the elephant, and four small incisors grew from the upper and lower jaw that the growth of tusks had begun. At least three divergent groups of proboscideans evolved there from Moeritherium or close relatives.

Mature tusker camera trapped at a waterhole in Khao Ang Rue Nai

The next beast of elephantine build and bulk was the Deinotherium that was still not a true elephant. They became common in Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe during the Miocene Epoch. They were very large at 4 meters high with down curving tusks from the lower jaw. Surviving for 20 million years well into the Pleistocene Epoch, Deinotherium was clearly a very successful animal. About the same time Paleomastodon and Phiomia began to evolve and show the closet beginnings of a trunk allowing the species to feed higher off the ground.

Very old tuskless bull in Huai Kha Khaeng

At the beginning of the Miocene epoch about 24 million years ago, the ancestral Gomphotheres was the real commencement of Proboscidean diversity. There were literally hundreds of species at one point including mastodons and mammoths. Elephantidae is the family to which the modern elephant belongs and the first species was Elephas antiquus from the middle to late Pleistocene Epoch. However, by the beginning of the Holocene Epoch around 10,000 years ago, only two species remained: African elephants Loxodonta africana and Asian elephants Elephas maximus.

Tusker in Khao Ang Rue Nai

The main differences between the two species are anatomical. The African elephant are larger and has a more elongated skull, a trunk with deep rings, larger ears, a flat forehead and, in general, holds its head at a 45 – degree angel to the ground. Asian elephants are smaller and have a double – bulged forehead, a trunk with fewer rings, smaller ears and a skull with a 90 – degree orientation.

There are three Asian sub-species: the Sri Lankan elephant Elephas maximus maximus, the mainland elephant Elephas maximus indicus, and the Sumatran elephant Elephas maximus sumatranus, and two African sub-species: the bush elephant Loxodonta africana africana, and the forest elephant Loxodonta africana cyclotis.

Young tusker camera trapped at a waterhole in Huai Kah Khaeng

Prehistoric fossil evidence of proboscideans has been discovered in the north, the northeast, the central plains, and the south of Thailand. The first find in 1948 was fossil bones of Stegodon insignis (mastodon) during the construction of the bridge across the river just south of Nakorn Sawan provincial city. Following this, discoveries were made in lignite deposits in Lamphun, Lampang and Phayao provinces. Fossil teeth of a Deinotherium at Ban Sop Khan in Phayao have been uncovered. Another find new to science is the earliest known species Stegolophodon praelatidens fossils from the Early Miocene discovered in Lamphun and Lampang by Pascal Tassy (from France) and others.

Many extraordinary ancient proboscidean fossils have been unearthed in Nakhon Ratchasima (Korat) province at the Tha Chang and Chang Thong sand pits along the Mun River in Chaloem Prakiat district going back to the middle Miocene about 16 million years ago. Eight different genera of proboscideans have been discovered here and is a testimony to the Kingdom’s fossil record.

Family unit in Huai Kha Khaeng

About 150 years ago, wild elephants were surviving around Bangkok along the Chao Phraya River, and in the districts of Rangsit, Bang Sue, Bang Kapi and Bang Na. The ‘City of Angles’ was a real jungle back then. It seems difficult to believe but in those days, Thailand was almost completely covered by forest cover – more than 90 percent. Today, only 30 percent remains. Due to the immense destruction, elephants have been at the forefront of a disappearing habitat.

The best current estimates say there are no more than 2,500-3,000 elephants surviving in the wild of Thailand today. There are 60 protected areas that have less than a hundred elephants, and another eight protected areas that have over one hundred individuals as follows: Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary – 280-300; Khao Yai National Park – 200; Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary – 230; Salak Phra Wildlife Sanctuary – 175-200; Phu Luang Wildlife Sanctuary – 100; Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary – 135; Kui Buri National Park – 150 and Kaeng Krachan National Park – 115. Surely, an up-to-date consensus of the wild elephant population should be undertaken by the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP) in all the forests throughout the Kingdom, and a report published as soon as possible. As it stands, many of these quotes are mere guesstimates.

Young tusker on the road in Khao Yai National Park

Elephants have been persecuted for a long time. The following scenario has been chosen for this column and has been carried out for decades in Thailand’s forests, and unfortunately is the dark side of nature that carries on to this day. Gunshots reverberate explosively through the forest panicking and scattering a herd of wild elephants. The huge beasts instinctively flee as fast as they can through heavy foliage away from the cacophony. In minutes, the forest returns to normal but the sad fact is humans have just disrupted the herd permanently. A baby elephant mills aimlessly around its mother lying dead on the ground. The confused calf has no sense of danger as poachers move in and capture it to be sold on the illegal black market. The calf will likely be forced to wander city streets or work in tourist camps.

Such atrocities are still practiced by some unscrupulous people intent on killing the mother solely to capture the baby. Many other animals are also hunted down in much the same way like gibbons and monkeys. Middleman and end-use buyers perpetuate this market and seem to evade the law. Wildlife black-market trading is fueled by a few shady individuals and is on-going. Great strides have been achieved by a few wildlife enforcement agencies and many arrests have been made in recent years exposing these law-breaking individuals. However, the so-called ‘big fish’ continue to do business as usual. It is a never-ending battle!

Mature tusker on the road in Khao Yai

In another scenario, a mature bull elephant with a large set of tusks tramples and gores a man deep in a protected forest many days walk from the nearest village. News travels fast but is subdued by the authorities due to the sensitive nature of the incident. The man was with a group of poachers hunting the tusker and he was armed with a crude muzzleloader. He was separated from the group and came upon the huge herbivore firing a shot, which only enticed the old bull to charge. It was all over in seconds and when the man was found critically injured the group rushed him to the nearest medical facility but it was too late. The villagers cried fowl and hunted the old bull down eventually taking his tusks and selling them to a middleman for pennies compared to what they would fetch from a rich end-user or agent. This has been going on for ages to feed the illegal ivory trade.

Human settlement, agriculture and roads have taken over much of the elephant’s habitat. Villages spring up in old elephant terrain, and the trespassers expect the giants to simply fade away into the forest. But elephants can develop a taste for crops grown by farmers, and they often take what they want. Countless conflicts have arisen between villagers and the real owners of the land, whose ancestors have lived there for many thousands of years. Thailand is not alone to crop-raiding elephants. Other countries in Asia and Africa have experienced the same outcome when humans have taken over elephant land.

Very young tusker about five years old in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

Most of the conservation areas where wild elephants live are just small isolated pieces, and agricultural areas or towns surround these forests, a major obstruction to natural breeding. Elephants in each forest are caught on islands and cannot walk back and forth between these areas. Thus, inbreeding among close relatives is inevitable, which leads to an inferior population and causes genetic diseases, and ultimately, to extinction. Belinda Stewart-Cox with Elephant Conservation Network has campaigned relentlessly for the establishment of a corridor between Salakpra and Srinakarin protected areas in order to prevent the total isolation of Salakpra’s elephants. Other corridors in other parts of Thailand are on the drawing boards.

The young tusker a month earlier

Elephants have been maimed and killed by poisoning, pungee stakes and pit-falls, gunshots, and electrocution. They have been chased out of rice paddies, mango orchards, and pineapple and tapioca fields. The use of fireworks, bright lights and gunshots scare them away temporarily, but the elephants are intelligent enough to lose their fear of such ruses. Elephants grow bolder and go on the rampage, sometimes killing people, tearing up villages and damaging DNP facilities usually during the dry season when water is scarce.

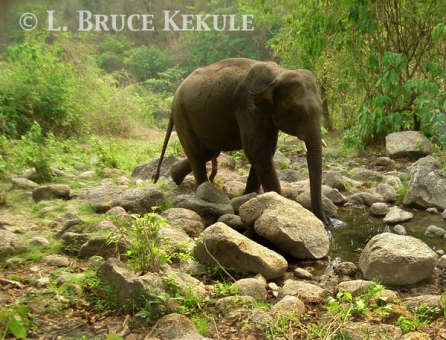

Nick-named ‘Nong Saeng’ after the sanctuary

This year, a herd of wild elephants in a western national park raided a village and broke into a shack with fertilizer. A young calf gorged itself and died shortly thereafter. On the other side of the spectrum, an old tuskless bull killed a ranger in western Thailand, and a tusker gored a villager in the East. Wild elephants have also died or been injured accidently by vehicles speeding on roads in some protected areas. Most of the accidents occur at night when the elephants are difficult to see. Some conservation organizations have erected new signs in some areas warning drivers the danger of elephants on the road at night.

Mature tuskless bull in Kaeng Krachan National Park

These noble beasts have featured prominently in almost every important historical event in the Kingdom. They are national, royal, and religious icons of Thailand. The ‘white elephant’ was on the flag of Siam. They are a national symbol of pride and joy. The Thai elephant’s survival lies in the hands of those responsible for these vanishing Asian giants. Proactive conservation awareness is a top priority for the government and existing outdated laws (some a hundred years old) need to be reviewed and changed for the elephant’s future. Strict penalties and fines for poaching and encroachment need to be enforced to insure the survival of nature’s largest terrestrial mammal in Thailand before it is too late.

Ecology and behavior of elephants:

“Tractors of the forest” is what the late Mark Graham called wild elephants in his excellent book entitled ‘Thailand’s Vanishing Flora and Fauna’ co-authored by Philip Round, the eminent bird ornithologist. Graham went on to say “in all parts of Khao Yai National Park there are trails which have been used by herds of elephants for, in all probability, thousands of years”. This trait is evident throughout continental Thailand where these creatures roamed.

Tusker about 25 years old in Kaeng Krachan

Asian elephants consume 75-150 kilograms of food and about 80-160 liters of water per day. A variety of grass species including bamboo is consumed, as well as tender twigs, barks, leaves and fruit. Natural mineral deposits are also very important to these herbivores supplementing their diet. An adult mainland Asian elephant may reach a height of 3.5 meters and weigh 5,000 kilograms. Elephants form family units but lone bulls are common. Male elephants have tusks but tuskless bulls are now quite common and can be very bad tempered, especially if the bull is in a state known as ‘musth’ where fluid leaks from the temporal gland.

Mature tusker at a waterhole in Khao Ang Rue Nai

Reproduction of the Asian elephant is the same as the other sub-species. The young are born after a gestation period of 18-22 months. Elephants usually give birth to a single offspring, rarely twins, and more rarely triplets. A female elephant can give birth every 4-6 years, and has the potential of giving birth to seven offspring in her life. Life expectancy for elephants is 60-70 years.

Elephants in domestication:

Elephants are extremely intelligent creatures. For centuries, humans have taken elephants from the wild and turned them into many different uses such as war elephants, working elephants at logging sites, as pets, tourist attractions and street beggers.

Elephant on the highway in Ayuttaya province

My very close friend Richard Lair who works for the Forest Industry Organization at the Conservation Center in Lampang has worked with elephants for many years. He was the first to get elephants to paint in Thailand, and the first in the world to establish a musical band made up entirely of elephants. He has produced several CD’s of this accomplishment.

Begging elephant near the 700 year stadium in Chiang Mai

Probably the most appalling fate for a domesticated elephant is to become a ‘street walker’. These magnificent creatures are forced to saunter hot, dusty and polluted streets of Thai cities ‘begging’ for food and money. Stories about elephants hit by cars and falling into drainage ditches, plus other accidents have been documented. At one time, a trip at night around Bangkok and other cities in the Kingdom one was greeted by a huge gray beast with a red light and a flashing CD attached to its tail. Continuous calls for change went unnoticed by mahouts and the owners of these elephants who sneaked them into cities and tourist sites. Legislation concerning domesticated elephants remains old and out-dated, and law enforcement has also been very poor.

Domesticated elephants being trucked into Chiang Mai

In late-2010, I saw an elephant on the streets of Chiang Mai at night. I took a few photographs but just watched as the mahout and elephant went about their business of begging for money. However, the situation has improved and there are several new sanctuaries dedicated to helping both mahout and elephant. It seems that most of the elephants have left Bangkok but they are still found in the out-lying areas. Hopefully, one day, the street-walker will be a thing of the past and these magnificent creatures will be treated with the respect, love and admiration they deserve.

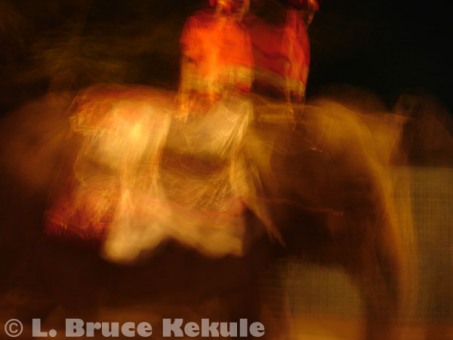

Elephant with handlers on the streets of Chiang Mai – An abstract

Big Cats in Kaeng Krachan: The tiger and leopard

A look at tiger and leopard evolution in Asia

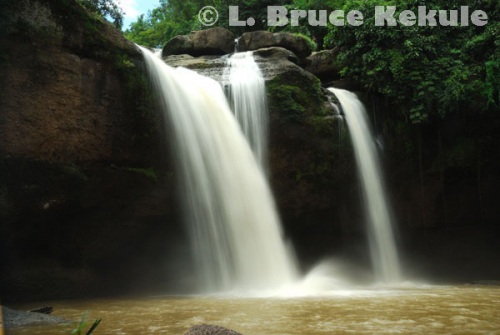

At the beginning of the dry season in January, the jungle canopy is still mostly green but falling leaves begin to carpet the forest floor as the first cold snap arrives. Some species of trees start their transformation, producing a mosaic of yellows, oranges, reds, browns and greens. For the first few hours each morning, heavy fog blocks out the sun as moisture dissipates from the forest. The Phetchaburi River is crystal clear as it flows through this magnificent forest.

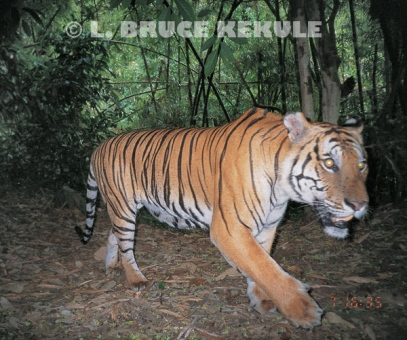

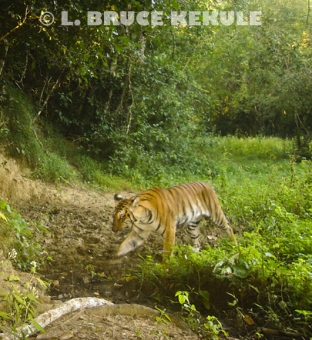

Indochinese tiger camera trapped by the Phetchaburi River

A large predator walks the trails seeking its next meal. Sensing danger, a muntjac barks a warning. The whole community of wild animals is on alert as macaques and langurs cry out from the trees above. A striped carnivore stalks a herd of wild pigs. The nervous omnivores squeal and panic, running through the underbrush to escape. But the big cat is lightning quick – it catches a young pig with sharp claws. The struggle is over in seconds as fangs penetrate to the spine.

Leopard camera-trapped on an old logging road

The tiger has just made a kill. It lifts the lifeless prey into deep cover and devours the carcass. After feeding, the big cat seeks water for a thirst quenching drink. It will then lie down and rest until the desire to eat or drink begins again. Tigers will sometimes move great distances in search of food. But where there is an abundance of prey species, these magnificent cats continue to live in balance with nature. The average kill ratio for a tiger is about twenty unsuccessful attempts for one actual kill. At a certain time of year, the male tiger will seek out a female to carry on his legacy.

Another tiger by the Phetchaburi River

Kaeng Krachan National Park is a great wilderness that sits in the Tenassarim Range in southwest Thailand. It is one of the most beautiful protected areas left in the country. Elephants, gaur, tiger, leopard, tapir, gibbons, hornbills and literally thousands of other plants and animals still survive in a rich ecosystem that is world class.

A tiger camera trapped at a mineral lick in Kaeng Krachan

To understand how the tiger and leopard evolved, we must go back to the beginning of these wild creatures. After the carnivorous dinosaurs died out about 65 million years ago, mammals with sharp teeth, strong jaws and claws replaced them as the top land predators. The first successful mammalian carnivores were the Creodonts that evolved during the Eocene epoch 57-35 million years ago. Creodonts ranged in size from smaller than a weasel to as big as a bear. A bear-dog also evolved during this period. These carnivores all had voracious appetites that were satisfied by large concentrations of prey species, mainly the odd-toed and even-toed ungulates that browsed and grazed the lush forests and plains of the time. The early Creodonts evolved into the modern carnivores that we know today: the bears, cats, dogs and other predators.

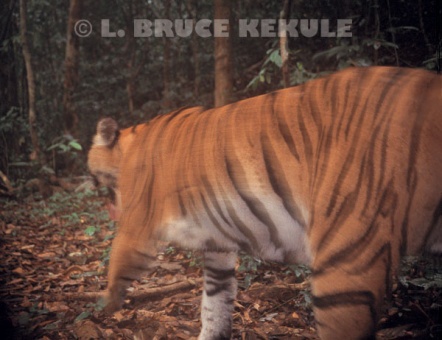

Tiger camera trap abstract

The order Carnivora is separated into three superfamilies: The Arctoidea includes marten, weasel, badger, otter, bear and the panda; the Cynoidea are made up of the dog, fox and the wolf; and the Herpestoidea includes the mongoose, civet, hyena and the cat. Most carnivores are dedicated meat-eaters, but some groups such as civet, panda and bear are omnivorous, eating meat and plants.

Leopard camera trapped on a nature trail in the park

Nimravidae were the first cats to evolve in the Early Oligocene epoch, about 35 million years ago. They lasted till the Late Miocene, some eight million years ago, when huge grasslands had developed around the world. The large saber-toothed cats were the first of the family Felidae. These long-fanged felines evolved alongside huge herds of grazing mammals like antelope and cattle. There were several different species of saber-tooth, but they all became extinct about two to three million years ago.

Black leopard camera trapped on the main road in the park

Modern cats belong to the family Felidae and include: tiger, lion, leopard, jaguar, cougar and cheetah, and all the smaller cats such as lynx, bobcat, jungle cat, fishing cat to name just a few plus domestic cats. Wild carnivores feed almost exclusively on vertebrate prey and sit at the top of the food chain. Tiger and lion have few predators apart from man but a pack of wild dogs however are a constant threat to the large cats and their offspring. The tiger and leopard belong to the genus Panthera, or roaring cats, that include the lion and the jaguar.

Leopard camera trapped in the interior

Thousands of years ago when primitive humans lived off the land as hunters and gatherers, they survived by pure instinct. They killed animals for meat and skins, and also gathered many different tools and plants from the forests. As humans became more sophisticated, they used weapons to take down larger animals. Clubs, spears, knives, bow and arrows were all that separated them from almost certain death at the claws and jaws of a predator many times their size.

Black leopard camera trapped on an old logging road

The possibility of being eaten by a carnivore like a tiger or leopard must have been on everyone’s mind that lived in or near the wilderness. Entering the forest where every step could be the last was like walking a tightrope. Attack normally lasted only seconds as a huge predator pounced from behind, biting the neck and causing almost instant death. Very few people survive such an incident. It must have been a scary environment to live in.

The will to survive, however, was strong and men eventually conquered his fear of the wild cats with more modern weaponry. The tables had finally turned and the predators became the hunted. As human populations and settlements grew, the forests were quickly transformed into agricultural land.

An Indochinese tiger on the prowl at night by the Phetchaburi River

After firearms were invented, European royalty, native kings, landlords, planters, foresters, government officials and many adventurers journeyed to the forests of Asia in search of the tiger. Mostly, they came to prove their dominance over the big cat. A trophy of tiger on the wall or floor at home proved beyond doubt that the owner was the supreme species. One could boast of their prowess as a hunter.

But the fact is most hunters shot tigers and leopards from the safety of a tree-blind, vehicle or elephant back. The cats would be attracted to within gun range by cattle, buffalo or a goat used as bait. For special hunts, hundreds of local villagers were recruited as beaters, trackers and mahouts. To join a shikar (Indian word for the hunt) was the ultimate experience for the adventurous.

The same tiger as above a few moments later

More tigers have been killed for sport in India then anywhere else in the world. In the days of the Raj, it was common to see five, ten or twenty cats lying dead on the ground in front of a hunting party. The Maharajah of Surguja killed some 1,157 tigers during his reign. Some Englishmen claimed to have shot more than 100 tigers. Fortunately in 1972, the Indian government finally banned hunting because the tiger and many other species were threatened with extinction.

The most famous hunter ever to overcome his fear of the big Asian cats was Jim Corbett of India. From 1907 to 1939, he single-handedly dispatched scores of man-eating tigers and leopards. His book ‘Man-eaters of Kumaon’ is a classic. Some cats mentioned in the book had killed hundreds of people. Corbett National Park was established in his honor, and the Indo-Chinese subspecies of tiger Panthera tigris corbetti is named after him.

In Thailand, the tiger and the leopard were also hunted for sport but on a much smaller scale than in India. In the past, rural Thai people living near wilderness areas built houses high off the ground that protected them during the night. But daytime was another thing. If they worked in fields bordering thick jungle or they went into the forest, they risked their lives.

At the turn of the 20th Century as modern firearms, agriculture and transportation took hold in the Kingdom, the forests and wildlife began to disappear. Man-eaters also declined. However, during World War II along the death railway in the Sai Yok district of Kanchanaburi province there were still accounts of man-eating cats. In recent times, there has been no such record. From time to time, domestic cattle are still killed by a tiger or leopard but this is now very rare. Low wildlife densities in the forest and easy prey are the main reason for this occurrence.

Thailand is fortunate in that tiger and leopard plus another seven species of cat still survive in some of the larger national parks and wildlife sanctuaries. Kaeng Krachan National Park is one of those protected areas that still harbor the big cats. Tigers can and do kill the leopard. Although their paths do cross, normally the spotted cat will avoid the striped predator. Documentary accounts and photographs do exist of tigers eating leopards.

In 2002-2003 while carrying out camera trap work in Kaeng Krachan in cooperation with the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department, I was surprised and elated to see both species tripping the same cameras in several areas only days apart. In one month, four different leopards, one of them black, were caught on film. In the following month, a leopard was caught during the day, and a huge male tiger stopped and posed for the camera. Both species were using the same trail for their hunting forays. A few other protected areas like Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai Naresuan wildlife sanctuaries have records of overlapping.

In Kaeng Krachan, an important discovery is that tiger and leopard hunt at all times during the day. It is usually thought they are only active in the late afternoon and throughout the night preferring to rest during the day. More research is required if we are to determine the pattern of daytime hunting by the big cats here. It is probably due to the pristine state of this forest and the lack of human activity.

Without doubt, the future of the big cats depends on one thing only – the complete protection of the remaining forests where they live. If the national parks and wildlife sanctuaries remain intact with a high number of prey species, the big cats will survive. But if overdevelopment and encroachment is allowed to continue, these magnificent animals will eventually disappear.

Unfortunately, too much time and money is wasted by too many organizations talking about saving the tiger and other wildlife, with very little actually being done. Human population growth will eventually destroy most wild places. Only true protection by a few dedicated people will slow the destruction of nature’s precious wildlife and wilderness areas. It is only hoped that the tiger and leopard will continue to survive as they have for millions of years.

Leopard – Panthera pardus

The leopard is closely related to the jaguar of South America. Both have a spotted coat pattern, incidence of melanism (black phase), and relatively short legs. The present distribution of the leopard is restricted to Asia Minor, India, Southeast Asia, the Himalayas, Tibet, China, Siberia, and Africa. Fossils of leopards were found in Pleistocene deposits throughout Europe, the Middle East, Java, and Africa, some 1.5 million years old. These secretive cats are mainly nocturnal. Their populations and ranges are difficult to determine but radio tracking of collared animals has shed new light on their movements and area they live in. ‘Spots’ is more tolerable to humans and their settlements.

Tiger – Panthera tigris

According to fossil evidence Panthera cats branched from the other Felidae about five million years ago in Asia. The first tigers originated in eastern China. Fossils of the earliest tigers date back to the Pleistocene epoch, about 1.6 to two million years ago, have been found in Henan, southeast China, and on the island of Java in Indonesia. The historic range of the tiger covered much of Asia and some of its islands.

However, humans have had an enormous impact on the geographic range of the species. The big cat only survives in 13 countries: Russia, China, India, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Burma, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. The present range is less than five percent of the tiger’s former range. There are less than 5,000 tigers left in the wild.

Elephants : Killing for Cash

THE SAGA OF ‘PANG DURIAN’: An orphaned baby elephant from Phraektakor Reserved Forest in Phetchaburi province close to Kaeng Krachan National Park

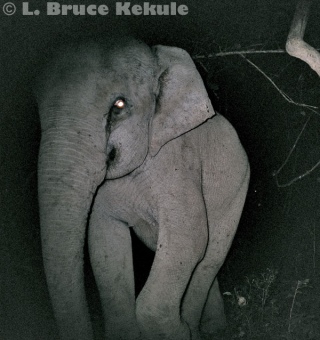

‘Pang Durian’ in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Elephants are being slaughtered in supposedly protected forests so that their young can be used to beg for money on the streets of Bangkok and other cities around the Kingdom. ‘Pang Durian’ is one of those orphaned baby elephants. But unlike other victims of this cruel trade, she has found a new family in the wild. This story is true and based on fact!

‘Pang Durian’ and two step-mothers in Kaeng krachan

A baby elephant wanders aimlessly around her mother lying dead on the ground. The confused young creature has no idea what the future holds as poachers move in to capture her. Her freedom is about to be taken away. Later her spirit will be broken and she will probably end up begging for food and money in some big town or tourist destination

The above scenario is all too common. The killing of mother elephants is perpetrated by some very unscrupulous people who then grab their young and sell them for cash. Other indigenous species like gibbon and langur are hunted down in a similar manner. The middleman and eventual buyers who create the demand for animals snatched from the wild seem to be insulated from the law. When will the killing and kidnapping stop?

Mother and baby tusker camera trapped at a mineral deposit in Kaeng Krachan

The cruelty of this illicit trade is epitomised by the remarkable but traumatic experience of ‘Pang Durian’, a female baby elephant abducted from Phraektakor Reserved Forest, just south of Kaeng Krachan National Park in Phetchaburi province. Her mother was killed by poachers in 1998 and the six-month-old was being kept at Ban Durian, a village just outside the park’s southern boundary. It was there, as she awaited sale on the black market, that she was given her name.

The young orphan was in very poor health. Luckily, however, Royal Forest Department (RFD) rangers in Kaeng Krachan heard about her and investigated. By the time they got to her, she was suffering from a deficiency of protein, calcium and other minerals that would normally come from mother’s milk. Her left leg had become bow shaped and deformed. The villagers hadn’t provided a nutritious, well-balanced diet, and malnutrition had set in.

Elephant family unit in Kaeng Krachan

After negotiations, ‘Pang Durian’ was traded for raw rice, other foodstuffs and construction materials. Shutat Sapphu, head of Ban Krang station in the park, took responsibility and looked after her for several months. Non-governmental organisations including the Wildlife Fund Thailand and Wild Animal Rescue Foundation took an interest in Pang Durian’s plight. After her health began to improve, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF-Thailand) moved her to the well-established Elephant Hospital at Mae Yao Reserve Forest in Lampang. For the next six months, she was in good hands. And her life was about to change for the better. Reintroduction into the wild was the plan.

In 1996, during a state visit to Thailand by Britain’s Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip (then president of the WWF-International), Her Majesty the Queen announced her intention to initiate a reintroduction project for elephants in the Kingdom . The idea was to offer an alternative future to domesticated and traumatised elephants, to let them live out the remainder of their lives as nature had intended.

Family unit camera trapped in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Santuary

In January of 1997, the process officially began when Her Majesty released the first three female elephants ‘Pang Bualoi’, ‘Pang Boonmee’ and ‘Pang Malai’ into Doi Pha Muang Wildlife Sanctuary in Lampang. In February 1998, ‘Pang Sangwan’ and ‘Pang Khamnoi’ were let loose in the same sanctuary as, exactly a year later, were Pang Kammoon and her one-year-old male calf, Plai Song. (“Pang” and “Plai” are Thai prefixes denoting female and male elephants, respectively.)

Some 50 elephants are currently being kept in Lampang for future release and other wilderness areas are now being looked at for inclusion in the project, for which the government recently allocated a budget of 100 million baht. Support for the scheme has come from agencies including the Bureau of the Royal Household, the Thai Elephants Conservation Centre, the Forest Industry Organisation, RFD and WWF.

It was decided to release ‘Pang Durian’ along with four adult elephants (two male, two female) into Kaeng Krachan, the Kingdom’s largest national park. According to the park chief, there are about 200 wild elephants, in seven or eight different herds, living in the interior. The question is, after having become used to humans can elephants be introduced into an area where wild ones roam?

By now ‘Durian’ was more than two years old but she would still be very vulnerable to attack by tigers and leopards and susceptible to possibly recapture by humans. So two stepmothers, ‘Pang Buangern’ (Silver Lotus) and ‘Pang Buathong’ (Golden Lotus), were assigned to look after and protect her. The two males in the group bore the names ‘Plai Eak’ and ‘Plai Mangkorn’ — the latter a bull aged about 60.

Tuskless bull camera trapped on an old logging road in Kaeng Krachan

In late May 2000, the five elephants made the 900-kilometre trip from Lampang south to Phetchaburi; it took about 24 hours to cover the distance. A veterinarian named Dr Somkiat Trongwongsa along with a team of mahouts and RFD rangers working with WWF-Thailand were assigned to look after and monitor the group. One of the females had been fitted with a radio collar for satellite tracking. The group were released near the main entrance at Sam Yot (Three Peaks) Gate into Kaeng Krachan on June 1 of that year.

Sadly, ‘Plai Mangkorn’ was found dead of old age six months later, but the rest of the group continued to move in and out of the park. After the intense rains in late 2000, contact was lost for several months, but in mid-2001 the three surviving adults in the group were spotted near Sam Yot Gate. But Durian had disappeared and everyone feared the worst. Had she been taken by a tiger or lost in the thick jungle?

A tusker camera trapped by the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan

The three adults hung around the gate, refusing to go back into the park. It transpired that they had been chased away from several villages in the vicinity and were becoming a serious problem for the RFD. Eventually, almost a year after their release, it was decided that they should be sent back to Lampang.

In September 2002, while working with the RFD in Kaeng Krachan in conjunction with WWF-Thailand, I made a trip into the park to set up some infra-red camera-traps at mineral licks about 12 kilometres from Sam Yot Gate. The cameras were attached to trees on trails leading to the salt licks and left for one month.

‘Pang Durian’ camera trapped in Kaeng Krachan showing her bowed left front leg

Positive proof that she was surviving with a wild herd in the park

When the films were processed in October, low and behold, ‘Pang Durian’ was spotted passing one of the cameras at about 4 o’clock one morning, her deformed left leg clearly visible. It almost seemed as if she was saying, “Here I am!” Other elephants captured on the same roll of film around the same time meant that this remarkable little elephant was now obviously in good hands. She had come full circle and had been adopted by a herd. A magnificent testimony to the tenacity of Thai elephants and a wonderful Walt Disney ending to the whole scenario.

Actually, RFD rangers had told me earlier that they’d spotted ‘Durian’ one night near Ban Krang station. But this camera trap photo confirmed her continued existence in the park and the partial success of a difficult yet ultimately rewarding reintroduction program. According to Dr Somkiat, the Durian success story indicates that it will only be feasible to reintroduce young elephants, about five years old, into wild populations. A year later, I believe I caught her again on a camera trap but it was more difficult to identify her so I’m not sure if it was her or not. Someday I will find this photograph and re-evaluate it.

Tuskless bull in a mineral deposit in Kaeng Krachan

Countless conflicts have arisen between villagers and the real owners of the land; the creatures whose ancestors have lived there for thousands of years. Many elephants have been persecuted and killed by poisoning, gunshot wounds and electrocution (electric fences carrying an alternating current of 220 volts are used). Fireworks are set off to chase them out of mango orchards and pineapple plantations. But this tactic only frightens them temporarily; the elephants get bolder. Some have gone on the rampage tearing up villagers’ houses, RFD buildings and other facilities.

Wild elephants have also been killed or maimed by vehicles traveling along paved roads in protected areas where there are no speed limits in force. Accidents usually happen at night when the animals are difficult to spot until it is too late.

Young tusker elephant in Khao Ang Rue Nai just before

it was killed by a reckless driver on the road through the sanctuary

Above is a young tusker I camera trapped in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary in Eastern Thailand. Two weeks after, he was hit and killed more than twenty kilometers away by a truck traveling at high speed on the road through the sanctuary. The driver was also killed but his wife next to him survived. The powers-to be have now closed the road from 9pm to 5am to allow animals freedom to use the road during the night. Road kill has dropped more than 50 percent and is considered a success in wildlife conservation and the authorities should be commended for taking action. This young tusker did not die in vain

Probably the most appalling treatment meted out to pachyderms is the beatings baby elephants snatched from the wild have to endure as their captors try to make them toe the line. Most are fed totally unsuitable food that lacks the necessary protein, minerals and vitamins. Later, these youngsters will be forced to ply the hot, dusty polluted streets of Thai towns begging for food and money.

Given the lax legislation concerning domesticated elephants, and poor enforcement, the future for these unfortunate animals is bleak. Continuous calls for change are ignored. Mahouts are still bringing elephants into urban areas and tourist traps. At one time, driving around Bangkok at night and you were almost certain to spot a huge gray beast plodding along with a red light or a CD attached to its tail. Even though this has been stopped by the BMA city officials, it still goes on in other parts of Thailand where there are late-night eateries and tourists.

One can only hope that the ‘Pang Durian’ success story will wake people up to the plight of these noble beasts which has played such an important role in Thai traditions, belief systems, culture, society and politics, and which has been involved in almost every important event in the Kingdom’s history.

Once featured on the Thai flag, the elephant is still a national symbol in which we should take pride. It needs our love and compassion, plus our help and respect. Without that, the magnificent Asian elephant is doomed.

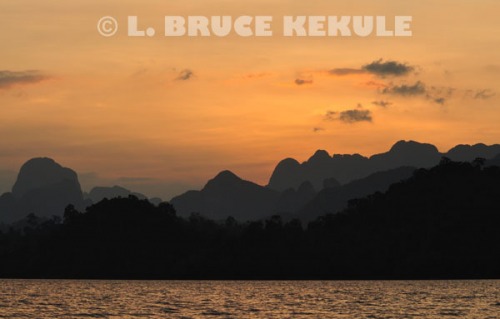

Khlong Saeng: The Lost River

One of the Kingdom’s top wildlife sanctuaries still harboring many endangered but classic Asian animals

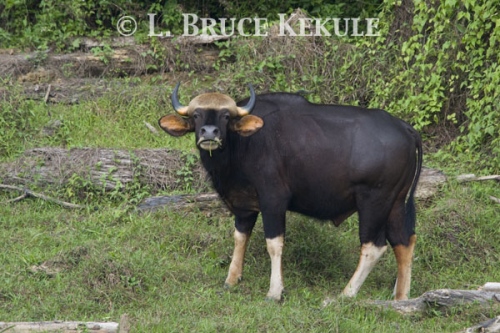

The weather is mostly clear as the sun drops behind a huge cloud close to the horizon. Light monsoon rains have begun at the end of April but hang in the mountains to the west. It has been a scorcher and heat from the day lingers over the reservoir. The light is soft and warm. About 6pm, a small herd of gaur drift out of the forest to drink at the waters’ edge and forage tender new grass. In a boat-blind about a kilometer away, I silently motor the craft closer using a battery operated trolling motor. The timing is perfect as I move in for a shot of Thailand’s magnificent but endangered wild ox.

Gaur cow in late afternoon light in Khlong Saeng

As I get closer, a mature cow feeding on an island in the lake sees something moving 100 meters offshore, and swims across to the mainland to investigate, all the time keeping her eyes locked on the strange anomaly moving in the water. Water drips from her underbelly, and her reddish-brown coat and deeply curved horns standout in the late-afternoon magic. I fire off a salvo of images hoping my camera and lens will capture this beautiful creature so late in the day. For a few brief moments, the old cow showcases Thailand’s natural heritage.

Young gaur bull

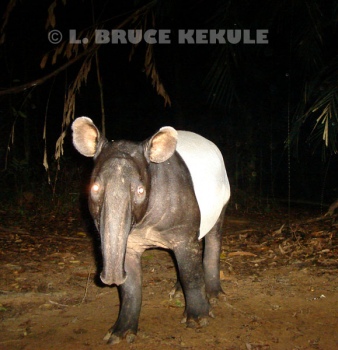

There are many beautiful forests in the South, but one in particular is truly a tribute to nature. Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary was once a magnificent natural watershed that provided water throughout the year to the inhabitants of the lowlands on the east side of the Thai Peninsula. It still harbors some very impressive animals such as elephant, gaur, tapir, serow, sambar, clouded leopard, sun bear, Great Argus (second largest of the pheasant family in Thailand), and the mighty king cobra – and the list goes on.

Gaur calf

Royal Decree encompassing 1,155 square kilometers of dense forest established Khlong Saeng in 1974. The sanctuary is the biggest in the Khlong Saeng – Khao Sok Forest Complex totaling more than 5,316 square kilometers and incorporating 12 protected areas, 11 of which are terrestrial and one with offshore islands in the Andaman Sea. Its forests are predominantly moist evergreen and most of the plants and animals are of Sundaic origin with some Indochinese species interspersed.

Curious gaur cow

Situated in the provinces of Surat Thani, Phang Nga, Ranong and Chumphon, the complex includes: Khlong Saeng, Khlong Yan, Khlong Naka, Khuan Mai Yai and Ton Pariwat wildlife sanctuaries, and Khao Sok, Kaeng Krung, Lam Son, Sri Phang Nga, Khao Lampi – Hat Thai Muang, Khao Lak – Lam Ru and Khlong Phanom national parks. They are under the responsibility of the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department (DNP) to provide protection, management and staff.

Gaur in the late afternoon

Khlong is the southern Thai word for a tributary or canal. The main tributaries of the Khlong Saeng valley include the Saeng, Ya, Yan, Ake, Mon, Ye and Mui that made-up the mighty Khlong Pasaeng. This river ran wild from the Phuket Range down to the Mae Tapi River in Surat Thani and eventually into the Gulf of Thailand. The riverine habitat teamed with flora and fauna, and the ecosystem was absolutely pristine. Tigers and leopards lived alongside many prey species like sambar, muntjac and wild pig. Elephants and gaur were fairly common. It was a magnificent wilderness at one time.

Gaur cow and her calves

But in the mid-1980s, a drastic change to the Pasaeng River was to come about. To increase Thailand’s electrical power needs, and back when building hydroelectric dams was in vogue, it was decided by the Electrical Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT), a state enterprise, and the government, to construct the Rajaprabha Dam that eventually inundated a total of 165 square kilometers (65 sq. miles) of the Khlong Saeng valley to become the Chiew Larn reservoir in 1986. The water body extends into the sanctuary for more than 50 kilometers (30 miles) but is only about two kilometers at its widest point.

Flooded forest in Khlong Saeng

Where rivers and forest previously existed, large waterways now provided easy boat access to virgin wilderness. The skeletal forms of what were once huge forest trees stand as a reminder of what disappeared beneath the flood more than a quarter of a century ago. Some trees still stand but many have come crashing down especially up-stream where decaying is severe. Millions of plants and animals perished as the floodwaters rose. The late Seub Nakhasathien, one of Thailand’s hero’s of wildlife conservation plus rangers and wildlife researchers saved hundreds of stranded fauna caught on islands. There are some 160 of them scattered throughout the reservoir when water levels are low. Some denizens were able to swim and move to higher ground but not all. It was the beginning of a new ecosystem – a large lake with a very long and complicated shoreline.

White-bellied sea eagle with a fish

Probably the most impressive scenic site in the sanctuary is the massive limestone ‘karst’ formations that were formed sometime during the mid to late Permian over 200 million years ago. It was a time of widespread mountain-building and volcanic activity. Thailand was part of Gondwanaland that was still attached to Pangaea, the ‘Supercontinent’. These colossal outcrops, some reaching as high as 960 meters (3,150 feet), look almost ‘architectural’ in design and are as impressive as the famous towers in Phang Nga Bay to the south. These configurations are the remnants of a prehistoric coral reef that once thrived here.

King cobra hunting for prey

Of all the animals in Khlong Saeng, gaur is probably the icon of wildlife in the sanctuary. These bovid are now rare in Thailand surviving only in a handful of protected areas, but they thrive fairly well. However, this only occurs around the upper reaches of Khlong Saeng and several other tributaries. The population of gaur here is estimated to be about 100 individuals and is one of the Kingdom’s best reserves for the species due to the dense moist evergreen forest.

Osprey in the mid-day heat

Breeding seems to be healthy; as many calves and young gaur of various ages have been seen in several herds I photographed at this site. Large solitary bulls keep the herd in stable breeding condition. These herbivores need huge tracts of forest free of human presence to survive. Being extremely shy, these wild cattle flee on the first sign of man. Good availability of food, water and minerals are important to their survival and the sanctuary provides these in abundance. There are still some elephants but their numbers seem to have declined. Further downstream, human activity has all but obliterated the large mammals including the tiger, which has not been seen for more than twenty years, even after extensive camera-trap surveys carried out by the research unit at the sanctuary headquarters.

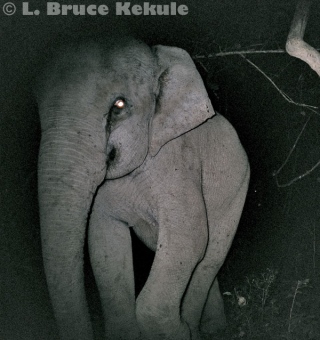

Young Asian Tapir camera-trapped

Next door to Khlong Saeng is Khao Sok National Park covering 739 Square kilometers established in 1980. Khao Sok is well known around the world. The national park’s mandate in Thailand is to promote and encourage tourism into various nature sites within the protected area. After the Rajaprabha dam was completed, boats and wooden rafts were built at an alarming rate to accommodate this new business of boating visitors into the lake. Now there are hundreds of craft, many extremely noisy. Fishing was allowed and it was a free-for-all in the beginning with everyman for himself. All forms of fishing were used including explosives, electricity, nets, trap-lines and spear guns. Many areas were quickly depleted of fish, and fisherman must now venture deeper into the reservoir trying to eek out a living.

Old bull gaur camera-trapped

Actually, the Fisheries Department (FD) has a regulation in place that states ‘no fishing’ is allowed from the dam five kilometers to the limestone cliffs during the breeding season from 15th May to 15th September. This ban should extend completely into Khlong Saeng. Unfortunately, there seems to be little or any formal protection in place as boats and people come and go with no restrictions. Also, in Khao Sok, there are many rafts that have extensive facilities including a ‘karaoke’, which seems distant from nature. Every year the FD releases several species of fish into the reservoir. The ‘giant catfish’, a species found in the Mekong River, was released here and are most likely competing with other large resident fish. The FD has banned its capture but all fish are being caught for the pot, or sale to waiting ice vendors at the dock.

Dusky langur on a stump

However, a more serious problem exists that needs immediate attention before it is too late. When the Rajaprabha hydroelectric dam was finished and working on-line, EGAT passed a regulation and transferred protection duties to Khao Sok National Park. This included the complete waterway and 100 meters up into the terrestrial landscape meaning the entire water body intrudes deep into Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary for more than 50 kilometers and the mandate for its use and protection is controlled by the national park. People easily penetrate Khlong Saeng to poach, gather and fish, and the sanctuary officials have no authority on the waterway. Budgets are low and therefore, protection and enforcement is minimal. It is an extremely large loophole that needs to be fixed soon!

Gaur cow feeding on grass

EGAT, DNP and FD should join forces to find a viable solution, and take corrective steps to re-zone the reservoir. The solution is easy. About 20 kilometers into the lake at the mouth of Khlong Mon, the lake narrows down to about two hundred meters across. A rope barrier and guard post has been erected by the sanctuary but is unmanned for the most part due to the national park’s mandate. Constant overfishing and visitation to the upper reaches of Khlong Saeng over the long run will definitely have a serious impact on this sanctuary, especially gaur due to their very shy nature. Another very sensitive species is the Great Argus. These beautiful birds will abandon a breeding site if disturbed by humans. There are six hornbill and two gibbon species indicating a pristine forest. Stump-tailed macaque is the largest primate and dusky langur or leaf-monkeys are common. White-bellied sea eagle, lesser fish-eagle and osprey plus otters depend on fish and even though there is still some species in abundance, saturation fishing will eradicate most fish over time.

Sunset over the Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

The DNP’s mandate for ‘wildlife sanctuaries’ is straightforward; they have been set aside for wild species propagation, biodiversity research and habitat preservation. With hundreds and possibly thousands of people visiting Khlong Saeng every year, it is doubtful whether the sanctuary can sustain its habitat diversity over the long term. Also, trash and oil pollution from the boats is serious problem that needs attention and constant surveillance.

Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary is a beautiful but forbidding forest, and its incredible biodiversity it a tribute to the Kingdom’s natural heritage. In terms of research, very little is actually known about the interior but its future depends on many things. Most of all; the protected area should become the focus of attention so that all concerned may take a hard long look and save it for the future. Decisive and quick action in the only recourse before it is too late.

In the field:

After more than a decade of visiting forests in the East, West and North, I decided it was about time I went down South. From January 2009, I began a photographic and camera-trap program in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary. Over the course of five months, a trip every month was scheduled. On the very first outing, we arrived at our final destination after a four-hour boat ride. I jumped onto a floating raft (ranger station) not far from the headwaters of the Khlong Saeng. After a few minutes of unpacking and getting settled in, someone shouted out that an elephant was by the waters’ edge across from the ranger station in plain sight.

Young tusker elephant in Khlong Saeng

What a strange bit of luck. We immediately jumped back in the boat and crossed over to where a young tusker was feeding on bamboo leaves and occasionally taking a drink from the lake. He was alone and we could not figure out why. Possibly the herd bull or an old belligerent cow elephant had pushed him out. We will never know. This little bull was in good condition and looked fine. The next day, I was back at the same spot waiting but he did not show. The morning after, he was back. I left the next day but before we parted company, I decided to name him ‘Nong Saeng’ after the river. I thought that would be the last time I would see the little youngster.

Young bull gaur

A month later I was back at the station and the first thing I asked; where was ‘Nong Saeng? No one had seen him. Two days later about 4pm while I was traveling up-river in my boat-blind, I bumped into him again, but much farther into the reservoir. He was back by the shoreline feeding and I was elated to say the least. I stopped the boat and had a great time photographing this lively young elephant once again. He was seen a couple more times by the rangers but since then, ‘Nong Saeng’ has probably gone up into the hinterland as the monsoon rains have begun. This encounter will always create fond memories of nature’s little quirks and how things work out sometimes. Hopefully, I will get a chance to see him again next year in January when I return to continue documenting the wildlife at Khlong Saeng.