Archive for September, 2009

Goats in the Mist: Thailand’s Goat-Antelopes

Goral and Serow – Rare goat-antelopes

Photographing endangered species has become an obsession to me. Many of Thailand’s wild animals have come so close to extinction that their numbers are counted not in thousands or even hundreds but rather handfuls. Goral Naemorhedus goral are one such animal. Surviving on a few scattered mountaintops in northern Thailand, these even-toed ungulates are on the critically endangered list. With fewer than 60 individuals nationwide and low numbers at each site, the goral is considered one of the Kingdom’s rarest mammals.

Goral kid in early morning light at Keiw Mae Pan cliff – Doi Inthanon NP

Acquiring photographs of these goat-antelopes is a daunting task considering their natural habitat. Hunting pressure and encroachment have forced them to retreat to the steepest, most inaccessible limestone cliffs and forested mountains. Goral are still found in seven protected areas including Doi Inthanon and Mae Ping National Parks, and in the wildlife sanctuaries of Om Koi, Doi Luang Chiang Dao, Mae Tuan, Mae Lao-Mae Sae and Lum Nam Pai, all in the north of Thailand.

Another species of goat-antelope surviving in Thailand is the serow Capricornis sumatraenis. Both species belong to the Bovidae family, which includes cattle, sheep, goats and antelope. Bovids are ruminants with four-chambered stomachs. In some areas, goral and serow share the same habitat. They have short bodies with long legs ending in padded, gripping hooves enabling them to inhabit steep mountainsides and cliffs. They eat grasses, herbs and shrubs and gain moisture from the plants they eat. Their keen eyesight provides early warning of danger. Like all bovids, they do not shed their horns like deer do with antlers. Serow are normally solitary whereas goral are usually form small herds from four to twelve individuals.

Male serow caught by camera trap

Serow and goral are creatures of habit. These lofty creatures have favorite places to sun themselves, usually a rock or grassy mound. They can stand for hours on one rock as I witnessed in Doi Inthanon where a goral stood from about 9am to almost 12noon. Another habit is to defecate at the same place. Piles of pellets can be found wherever they live, usually on or around a large rock. Research on both species has now been undertaken by Mahidol and Kasetsart University staff studying the impact of human settlements near goat habitat and surveying the remaining populations.

Unfortunately, both species have been hunted for their meat, horns and oil which comes from boiling the head. Supposedly, the oil is used to relieve arthritis and bone ailments. The horns of goral and serow are black, corrugated at the base, pointed and swept back (like their relatives, the Rocky Mountain goat of North America). Their horns are not impressive but are still sought after by poachers. The tip of serow horn is used to make deadly spears which can be attached to a rooster’s spur during a cock fight. It is eagerly sought after, especially in southern Thailand.

Goral kid close-up

Hunting has decimated both goral and serow populations that numbered in the thousands as recently as 50 years ago. In many mountainous areas hill tribe people live and encroach on the forest for the purpose of slash-and-burn agriculture. This has played a major role in the disappearance of both species in the North. Lowland people also hunted them. In other areas where the serow are found, they have declined due to continued pressure from man.

Two sites were chosen to photograph these mountain creatures: Doi Inthanon National Park about 80 kilometers south of Chiang Mai and Mae Lao-Mae Sae Wildlife Sanctuary some 60 kilometers to the north. Staff at the protected areas confirmed goral and serow were still surviving. Working closely with the Wildlife Research Division in Bangkok. My plan was to set up photographic blinds as close to wild goat domain as possible and use a long telephoto lens. But this was easier said then done.

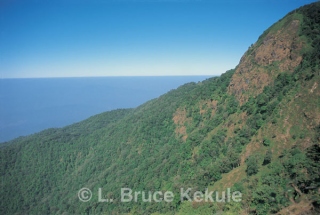

Keiw Mae Pan cliff in Doi Inthanon

Doi Inthanon, Thailand’s highest mountain, supports several small herds of goral around the summit. The animals are quite often seen close to Kew Mae Pan Nature Trail, developed in partnership with the Electric Generating Public Company Limited (EGCO) and the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department (DNP). Three kilometers from the road, a huge cliff rises some 2,500 meters above sea level and is criss-crossed with goat trails etched from thousands of years of use by goral and serow.

The skies are crystal clear over Doi Inthanon in November. This is truly a beautiful and remarkable place. But it does take some effort to get close to the cliff. The nature trail is strictly regulated and a local guide must be used for the three to four hour trek. If you are lucky and get up early, you may see goral and serow sunning themselves on rocky outcrops near the trail. Take a good pair of binoculars or telescope. This is also a good place for birdwatching, and you may see many species including the beautiful endemic green-tailed sunbird.

Doi Inthanon National Park

Mae Lao-Mae Sae is situated along the highway from Chiang Mai to Pai. A part of the sanctuary is divided by the road and Mon Liem, a giant granite massif, rises up to 1,200 meters above sea level. The sanctuary is home to a small herd of goral that survive on the summit. It is also criss-crossed by goat trails, and huge pine trees hundreds of years old are found here. The view is majestic, especially to the north where Doi Luang Chiang Dao Wildlife Sanctuary, another haven for goral, is situated. Wildlife sanctuaries are not open to the general public since they have been set aside for wildlife and biodiversity research. In October 2001, I glimpsed a male goral near the summit as the sun was going down. The goat unfortunately, was out of photographic range.

In November 2001, I visited the superintendent of Doi Inthanon to arrange a photographic trip after both goat species at the cliff. At 2,300 meters above sea level, temperatures can plunge at daybreak to zero degree Celsius with ice forming on the grass. It was tough getting out of the tent at 4 a.m. but it was important to move into the blind near the cliff face before the sun was up in order to photograph these wild goats. For the best photographic opportunities, the blind had to blend into the surrounding terrain so as not to spook the goats.

After four days of freezing, windy conditions, I spotted goral and serow on several occasions about a kilometer away. While scanning the cliff with my binoculars on the last morning, I detected a slight movement. A closer look revealed a male goral lying down on a buff about 500 meters from the blind. A short while later, he stood up. Using my 600mm Minolta lens with 2X tele-converter, I got some acceptable photographs of him.

This male had a fluffy white throat and underbelly. His gray winter coat was beautiful. After some time he did what goral do best – jumping straight down off the ledge in order to get closer to his mate who was feeding below. They butted heads affectionately a few times before disappearing into the maze of the cliff.

I made four trips to Doi Inthanon during the winter of 2001 and 2002 in search of goral and serow. Several herds of goral are still breeding here and can be seen almost every day. Serow are more elusive and only a few individuals were spotted from time to time. The spirits of the mountain listened to my prayers. On the last day of the fourth trip, a young goral about five months old appeared twenty meters away from me stamping its feet and snorting. It was nature at its best, making the front cover of this book.

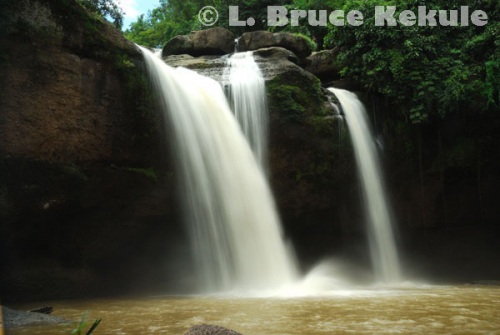

Siriphum Waterfall in Doi Inthanon National Park

These wild goats have an uncertain future. Uncontrolled human population growth both inside and outside of the protected areas is bound to affect them in the long run. There is also the danger of disease carried by domesticated cattle and buffalo around the mountaintops decimating wild goats – something that needs to be checked and stopped at all costs.

Hunting of goral and serow continues in some areas, and the poachers are rarely brought to justice. Jail terms are too light and outdated. As a result, these animals need serious efforts to protect them from the dangers of the modern world with all the resources available, or they could vanish from the Kingdom’s mountaintops forever. A crime against nature should be on par with a crime against a fellow human being. Enforcement must be improved and implemented on a long term-basis. The Thai community needs more wildlife conservation education at all levels of society.

Serow – Capricornis sumatraenis

Serow share much the same predicament as goral but with a larger world range, they have fared slightly better and can be found in many mountainous areas in the Kingdom. In a few places they live all the way down to sea level. These goat-antelopes still survive in the Himalayas, northern India, southern China, mainland Southeast Asia and Sumatra. Several subspecies have been recorded and most populations are localized.

Serow have black or dark-gray coarse hair and a long shaggy mane down their backs. Two subspecies of serow are recognized in Thailand: those found in the steep limestone mountains of the south have black legs and those surviving in the Tenasserim range and further north to Burma have rufous colored legs below the knee. Breeding lasts from October to November and a single kid is born after seven months of gestation. Occasionally, twins are born.

Goral – Naemorhedus goral

Goral are found from about 1000 up to 4,000 meters. Their range is from the Himalayas and northern India, to southern China, Burma and northern Thailand. The Thai species are mainly gray-brown in color much like the boulders and rocks that they live around. A thin black stripe runs along their spine to a short tail. As with other wild Asian bovids like gaur and banteng, goral have white stockings from the knee to the hoof. With white patches on their throat and underbelly that stands out in bright sunlight, goral are distinct. They are compact mammals that can move up and down vertical cliffs with ease, and are tough to spot in their habitat. The breeding season lasts from November to December. One or two kids may be born in May or June.

Elephants : Killing for Cash

THE SAGA OF ‘PANG DURIAN’: An orphaned baby elephant from Phraektakor Reserved Forest in Phetchaburi province close to Kaeng Krachan National Park

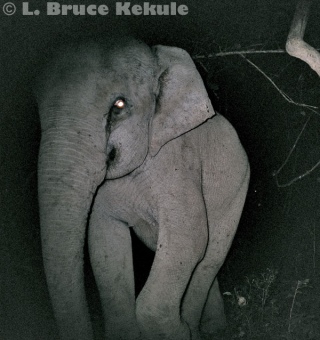

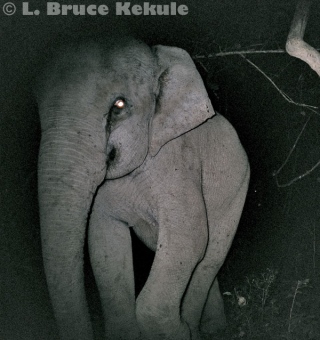

‘Pang Durian’ in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Elephants are being slaughtered in supposedly protected forests so that their young can be used to beg for money on the streets of Bangkok and other cities around the Kingdom. ‘Pang Durian’ is one of those orphaned baby elephants. But unlike other victims of this cruel trade, she has found a new family in the wild. This story is true and based on fact!

‘Pang Durian’ and two step-mothers in Kaeng krachan

A baby elephant wanders aimlessly around her mother lying dead on the ground. The confused young creature has no idea what the future holds as poachers move in to capture her. Her freedom is about to be taken away. Later her spirit will be broken and she will probably end up begging for food and money in some big town or tourist destination

The above scenario is all too common. The killing of mother elephants is perpetrated by some very unscrupulous people who then grab their young and sell them for cash. Other indigenous species like gibbon and langur are hunted down in a similar manner. The middleman and eventual buyers who create the demand for animals snatched from the wild seem to be insulated from the law. When will the killing and kidnapping stop?

Mother and baby tusker camera trapped at a mineral deposit in Kaeng Krachan

The cruelty of this illicit trade is epitomised by the remarkable but traumatic experience of ‘Pang Durian’, a female baby elephant abducted from Phraektakor Reserved Forest, just south of Kaeng Krachan National Park in Phetchaburi province. Her mother was killed by poachers in 1998 and the six-month-old was being kept at Ban Durian, a village just outside the park’s southern boundary. It was there, as she awaited sale on the black market, that she was given her name.

The young orphan was in very poor health. Luckily, however, Royal Forest Department (RFD) rangers in Kaeng Krachan heard about her and investigated. By the time they got to her, she was suffering from a deficiency of protein, calcium and other minerals that would normally come from mother’s milk. Her left leg had become bow shaped and deformed. The villagers hadn’t provided a nutritious, well-balanced diet, and malnutrition had set in.

Elephant family unit in Kaeng Krachan

After negotiations, ‘Pang Durian’ was traded for raw rice, other foodstuffs and construction materials. Shutat Sapphu, head of Ban Krang station in the park, took responsibility and looked after her for several months. Non-governmental organisations including the Wildlife Fund Thailand and Wild Animal Rescue Foundation took an interest in Pang Durian’s plight. After her health began to improve, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF-Thailand) moved her to the well-established Elephant Hospital at Mae Yao Reserve Forest in Lampang. For the next six months, she was in good hands. And her life was about to change for the better. Reintroduction into the wild was the plan.

In 1996, during a state visit to Thailand by Britain’s Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip (then president of the WWF-International), Her Majesty the Queen announced her intention to initiate a reintroduction project for elephants in the Kingdom . The idea was to offer an alternative future to domesticated and traumatised elephants, to let them live out the remainder of their lives as nature had intended.

Family unit camera trapped in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Santuary

In January of 1997, the process officially began when Her Majesty released the first three female elephants ‘Pang Bualoi’, ‘Pang Boonmee’ and ‘Pang Malai’ into Doi Pha Muang Wildlife Sanctuary in Lampang. In February 1998, ‘Pang Sangwan’ and ‘Pang Khamnoi’ were let loose in the same sanctuary as, exactly a year later, were Pang Kammoon and her one-year-old male calf, Plai Song. (“Pang” and “Plai” are Thai prefixes denoting female and male elephants, respectively.)

Some 50 elephants are currently being kept in Lampang for future release and other wilderness areas are now being looked at for inclusion in the project, for which the government recently allocated a budget of 100 million baht. Support for the scheme has come from agencies including the Bureau of the Royal Household, the Thai Elephants Conservation Centre, the Forest Industry Organisation, RFD and WWF.

It was decided to release ‘Pang Durian’ along with four adult elephants (two male, two female) into Kaeng Krachan, the Kingdom’s largest national park. According to the park chief, there are about 200 wild elephants, in seven or eight different herds, living in the interior. The question is, after having become used to humans can elephants be introduced into an area where wild ones roam?

By now ‘Durian’ was more than two years old but she would still be very vulnerable to attack by tigers and leopards and susceptible to possibly recapture by humans. So two stepmothers, ‘Pang Buangern’ (Silver Lotus) and ‘Pang Buathong’ (Golden Lotus), were assigned to look after and protect her. The two males in the group bore the names ‘Plai Eak’ and ‘Plai Mangkorn’ — the latter a bull aged about 60.

Tuskless bull camera trapped on an old logging road in Kaeng Krachan

In late May 2000, the five elephants made the 900-kilometre trip from Lampang south to Phetchaburi; it took about 24 hours to cover the distance. A veterinarian named Dr Somkiat Trongwongsa along with a team of mahouts and RFD rangers working with WWF-Thailand were assigned to look after and monitor the group. One of the females had been fitted with a radio collar for satellite tracking. The group were released near the main entrance at Sam Yot (Three Peaks) Gate into Kaeng Krachan on June 1 of that year.

Sadly, ‘Plai Mangkorn’ was found dead of old age six months later, but the rest of the group continued to move in and out of the park. After the intense rains in late 2000, contact was lost for several months, but in mid-2001 the three surviving adults in the group were spotted near Sam Yot Gate. But Durian had disappeared and everyone feared the worst. Had she been taken by a tiger or lost in the thick jungle?

A tusker camera trapped by the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan

The three adults hung around the gate, refusing to go back into the park. It transpired that they had been chased away from several villages in the vicinity and were becoming a serious problem for the RFD. Eventually, almost a year after their release, it was decided that they should be sent back to Lampang.

In September 2002, while working with the RFD in Kaeng Krachan in conjunction with WWF-Thailand, I made a trip into the park to set up some infra-red camera-traps at mineral licks about 12 kilometres from Sam Yot Gate. The cameras were attached to trees on trails leading to the salt licks and left for one month.

‘Pang Durian’ camera trapped in Kaeng Krachan showing her bowed left front leg

Positive proof that she was surviving with a wild herd in the park

When the films were processed in October, low and behold, ‘Pang Durian’ was spotted passing one of the cameras at about 4 o’clock one morning, her deformed left leg clearly visible. It almost seemed as if she was saying, “Here I am!” Other elephants captured on the same roll of film around the same time meant that this remarkable little elephant was now obviously in good hands. She had come full circle and had been adopted by a herd. A magnificent testimony to the tenacity of Thai elephants and a wonderful Walt Disney ending to the whole scenario.

Actually, RFD rangers had told me earlier that they’d spotted ‘Durian’ one night near Ban Krang station. But this camera trap photo confirmed her continued existence in the park and the partial success of a difficult yet ultimately rewarding reintroduction program. According to Dr Somkiat, the Durian success story indicates that it will only be feasible to reintroduce young elephants, about five years old, into wild populations. A year later, I believe I caught her again on a camera trap but it was more difficult to identify her so I’m not sure if it was her or not. Someday I will find this photograph and re-evaluate it.

Tuskless bull in a mineral deposit in Kaeng Krachan

Countless conflicts have arisen between villagers and the real owners of the land; the creatures whose ancestors have lived there for thousands of years. Many elephants have been persecuted and killed by poisoning, gunshot wounds and electrocution (electric fences carrying an alternating current of 220 volts are used). Fireworks are set off to chase them out of mango orchards and pineapple plantations. But this tactic only frightens them temporarily; the elephants get bolder. Some have gone on the rampage tearing up villagers’ houses, RFD buildings and other facilities.

Wild elephants have also been killed or maimed by vehicles traveling along paved roads in protected areas where there are no speed limits in force. Accidents usually happen at night when the animals are difficult to spot until it is too late.

Young tusker elephant in Khao Ang Rue Nai just before

it was killed by a reckless driver on the road through the sanctuary

Above is a young tusker I camera trapped in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary in Eastern Thailand. Two weeks after, he was hit and killed more than twenty kilometers away by a truck traveling at high speed on the road through the sanctuary. The driver was also killed but his wife next to him survived. The powers-to be have now closed the road from 9pm to 5am to allow animals freedom to use the road during the night. Road kill has dropped more than 50 percent and is considered a success in wildlife conservation and the authorities should be commended for taking action. This young tusker did not die in vain

Probably the most appalling treatment meted out to pachyderms is the beatings baby elephants snatched from the wild have to endure as their captors try to make them toe the line. Most are fed totally unsuitable food that lacks the necessary protein, minerals and vitamins. Later, these youngsters will be forced to ply the hot, dusty polluted streets of Thai towns begging for food and money.

Given the lax legislation concerning domesticated elephants, and poor enforcement, the future for these unfortunate animals is bleak. Continuous calls for change are ignored. Mahouts are still bringing elephants into urban areas and tourist traps. At one time, driving around Bangkok at night and you were almost certain to spot a huge gray beast plodding along with a red light or a CD attached to its tail. Even though this has been stopped by the BMA city officials, it still goes on in other parts of Thailand where there are late-night eateries and tourists.

One can only hope that the ‘Pang Durian’ success story will wake people up to the plight of these noble beasts which has played such an important role in Thai traditions, belief systems, culture, society and politics, and which has been involved in almost every important event in the Kingdom’s history.

Once featured on the Thai flag, the elephant is still a national symbol in which we should take pride. It needs our love and compassion, plus our help and respect. Without that, the magnificent Asian elephant is doomed.

Gurney’s Pitta – On the verge of extinction

The Gurney’s Pitta – Thailand’s rarest bird

Gurney’s Pitta in Khao Phra Bang Khram

The dark morning stillness of thick lowland rainforest of Khao Nor Chuchi, Krabi province, is broken by thumping footsteps as two humans move slowly down the trail. We carry heavy photographic equipment to a photo-blind set the previous evening, deep in the jungle. Precipitation is heavy as I set up in the hide. My helper departs quickly, conveying the message to the wildlife in the area that the intruders have left.

The ‘Emerald Pool in Khao Phra Bang Khram

Animals of the night fade into their homes and the ecosystem enters its daylight cycle. As morning light awakens the rainforest, sounds of dripping moisture begin to subside while forest birds and insects start their incessant calls as they have for millions of years.

Well hidden in the blind, I settle down, ever-vigilant for any movement on the forest floor. As the sun arches into the sky, light filters through the forest canopy in patches, illuminating the surroundings. There is a movement near the trail and a Hooded Pitta, common to this forest, hops about looking for food. The striking little blue-green bird with dark brown crown moves closer to the blind seemingly unconcerned about the looming structure.

Gurney’s pitta male

Snapping a few shots of the feathered creature but not wanting to alarm the other inhabitants of the forest, I continue to sit quietly hoping the spirits of the forest will answer my wish.

A morning rain shower passes by but quickly dissipates. As if on cue, a small black and yellow bird magically appears in front of the photo-blind, catching my eye. It’s the creature I’ve been waiting for: the Gurney’s Pitta!

Gurney’s pitta male

The little bird, perhaps sensing danger, quickly disappears into the darkness of the jungle but within minutes, is back again just long enough for only one shot with the camera.

The chance to see and photograph the Gurney’s Pitta, one of the rarest species in the world, has been my goal for several years. And this particular forest is the last known habitat for the bird which is both Thailand ‘s most endangered and a flagship species for the conservation of southern Thailand ‘s lowland rainforest.

Gurney’s pitta female

Gurney’s Pitta (Pitta gurneyi), or sometimes-called Black-breasted Pitta, is a small terrestrial forest bird endemic to Thailand and Burma . The male, with golden brown wings, bright yellow upper breast and flanks, black head and lower breast, white throat and brilliant iridescent blue crown and tail feathers, is striking indeed. The female is less colourful but, nevertheless, also very beautiful.

The species nests in spiny under-story palms laying three to four eggs but usually fledging at most two or three young. They hop about the forest floor and eat mainly insects and earthworms found amongst leaf litter but also take snails and little frogs.

Banded Pitta male

Extremely secretive, they keep as much jungle between themselves and any intruders. When danger approaches, they hop into the underbrush and disappear.

Of the world’s 31 known pittas, found from Africa to the Solomon Islands , and from Japan through Southeast Asia to New Guinea and Australia , 12 species are found in Thailand . They are Gurney’s, Giant, Banded, Hooded, Blue-winged, Blue, Blue-rumped, Eared, Mangrove, Garnet, Rusty-naped and Bar-bellied, of which the first five mentioned are found at Khao Nor Chuchi. The probable geographic origin of the Family Pittidae is in the Indo-Malayan region.

Banded Pitta female

Gurneys Pitta was first discovered in 1875 by W. Davison, a wildlife specimen collector working in Southern Burma for Allan Octavian Hume, a British civil servant working in India , and doyen of ornithology at that time. The bird was named after Humes friend, J.H. Gurney of the English county of Norfolk , and a fellow of the Zoological Society of London.

In the early 20th century, the bird was actually considered common in southern Thailand . Around the 1980s, it was thought to be extinct after no reported sightings had taken place for at least three decades. Then, in 1986, Philip Round, Thailand ‘s top birder, rediscovered the Gurney’s Pitta at Khao Nor Chuchi. It was big news for bird conservation groups and was heard around the world.

Historically, the world range of Gurney’s Pitta was a small concentrated area of lowland semi-evergreen forest along the coast and inland areas of the Thai peninsula, in the provinces of Trang, Krabi, Nakhon Si Thammarat, Surat Thani and Chumphon and Prachuap Khiri Khan. However, the once magnificent lowland tropical forest, its diversity of flora and fauna unsurpassed, has disappeared from most of those areas, due to man’s incessant greed, and his urge to destroy natural forest for the sake of agriculture and profit.

Khao Nor Chuchi, at Khao Pra-Bang Khram Wildlife Sanctuary, Khlong Thom district, Krabi, about 56 kilometres southeast of the provincial capital, is the last known site for Gurney’s Pitta in Thailand . Khao Pra-Bang Khram, with its headquarters at Ban Bang Tieo village, was established as a non-hunting area in 1987 by the Royal Forest Department (RFD), at the behest of Bangkok Bird Club (now Bird Conservation Society of Thailand-BCST), specifically in order to protect Gurney’s Pitta. It was upgraded to a wildlife sanctuary in 1993, with a total area of 183 square kilometres.

The Emerald Pool (Sa Morakot) within Khao Pra-Bang Khram Wildlife Sanctuary is a beauty spot visited by many local and foreign tourists. There are many trails open to nature explorers and bird watchers known as Thung Tieo Nature Trail Network. At least 318 different bird species have been recorded here.

The site’s alternative name, Khao Nor Chuchi, comes from the 650-metre-high conical mountain which overlooks the area. Bird photographers also come to Khao Nor Chuchi after images of the Gurney’s.

Many people, after travelling thousands of kilometres from different parts of the world, have left very disappointed after not seeing or photographing it. Gurney’s Pitta is a tough bird even to see, let alone photograph.

Although the species once occupied about 40 square kilometres of this area, most of the extreme lowlands where they live and breed were excluded from the sanctuary. As a result, forest is still being destroyed to grow rubber, oil palm and coffee, and human settlement has taken up most of the area.

Villagers still engage in poaching of animal and forest products from the reserved forest. On the day I photograph this Gurney’s Pitta, I still heard a gunshot.

Pitta numbers at Khao Nor Chuchi have declined drastically in the last two decades from an estimated 40 pairs in 1986, down to 21 pairs in 1992. This slide was due primarily to uncontrolled forest destruction, perhaps abetted by capture of the species for the black market trade in forest birds, and even for some government-run zoos.

According to BirdLife International’s Red Data there were only 11 breeding pairs and two extra males remaining in mid-2000. This year, only four to five nests have been found and sightings of individual birds have been minimal. At one nest that was abandoned, local birdwatchers found bird-nets put there by villagers who used the nets to capture the birds.

The species was also found along the coast and inland at the most southern tip of Burma but no reports of them have come from there since about 1914 and it is anybody’s guess whether it still survives. No surveys can be done due to inaccessibility of the area and danger of land mines. Tough government regulations have also kept most researchers away from the area.

BirdLife International, BirdLife Denmark , and NGOs such as BCST and the Oriental Bird Club have implemented a number of projects at Khao Nor Chuchi, in collaboration with RFDs Wildlife Conservation Division. However, these have slowed, but not halted, new settlements and further forest clearance.

Ultimately, unless the wildlife sanctuary can be expanded to encompass all remaining lowland forest, and previously cleared areas reforested, Gurney’s Pitta faces a very bleak outlook for survival. This magnificent bird could disappear before we know it and that would be a sad day for conservation in Thailand .

With just 11 breeding pairs left, the Gurney’s Pitta is very likely to be the first species to go extinct in this millennium, unless all parties concerned join hands in protecting it. On the day this male bird was photographed, a gunshot was heard.

Heavy storms and floods have closed the visitors’ road, and wildlife has thrived because rangers kept it closed

First published in October 2003

Just a three-hour drive southwest of Bangkok, along Phetchaburi province’s border with Burma, lies Kaeng Krachan – Thailand’s largest national park, encompassing 2,915 square kilometers of mostly tropical broad-leafed evergreen and mixed deciduous forests. In the interior live tigers, leopards, elephants, gaur, tapir and many other amazing species. Even the rare Siamese crocodile still lurks in one of the park’s watercourses. Kaeng Krachan is one of the country’s least touched forests.

Black Leopard phase

Prior to the government ban in 1989, logging was carried out in the lowland areas of Kaeng Krachan. Timber cutters cut an 18km road into the interior from Sam Yot Mountain to transport logs from the concession areas. When logging ceased, the Royal Forest Department extended the road another 18km to Phanern Thung Mountain to facilitate visitors to Thor Thip Waterfall.

Kaeng Krachan became a popular destination, with thousands of visitors each year. But too many visitors ruined some areas in the park. Wild creatures, especially mammals, faded into the more inaccessible areas and were not often seen along the road.

In October of 2002, two back-to-back violent tropical rainstorms hit Kaeng Krachan, overflowing the park’s streams and rivers, and inundating much of Phetchaburi province. Five local villagers, along with homes, vehicles, and livestock, were swept away in the worst flooding in more than 40 years. Blame for the flash floods was placed on excessive logging of the past.

Road washed out

There was extensive devastation inside the park as well. Floods washed away many sections of the main road, and more than 50 landslides uprooted trees and blocked access by tourists. The National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department (DNP) has to wait for funds to repair the road, and this takes time. That ended the flow of people in their noisy vehicles, and the wild creatures began to use the road in their search for food and water.

Yellow phase leopard in the interior

For the last few years I have worked with the RFD and later the DNP, to carry out infrared camera-trap surveys in Kaeng Krachan to monitor large and small mammals. Some exciting photographs have resulted. Tigers and leopards, both in black and yellow phases, have come into almost every camera trap. The big cats are also surviving in overlapping territories in quite a few areas, especially along the Phetchaburi River, and along the road close to the ranger station on Phanern Thung Mountain.

Indochinese Tiger camera-trapped

Last January, more than three months after the storms closed the road, was a great opportunity to camera-trap. Four camera-trap units were placed at Kilometres 31, 32, 33 and 35, and the units started photographing almost immediately.

Tigers and leopards were now using the road to hunt day and night, and creatures like the very rare Fea’s muntjac were also caught on film. Other animals such as Asian wild dogs, black bears, large Indian civets, leopard cats, common muntjac and porcupines were also camera-trapped.

Fea's muntjac camera-trapped

One of Kaeng Krachan’s biggest advantages (from the animals’ viewpoint) is that the rainy season makes its interior inaccessible. It is almost impossible to move in and out of the main Phetchaburi watershed area when the river is swollen by heavy rains, meaning from June to October. At present, the river is a raging torrent and only professional rope handlers could possibly hope to cross. And this doesn’t mention the leeches, which are everywhere.

Without human interference, the wildlife of Kaeng Krachan lives in total peace. The ecosystem rejuvenates itself.

An example: The staff at the national park headquarters decided to close an old logging road about 12km from the main gate at Sam Yot, securing it with a steel pipe barrier. No vehicles were allowed to enter this 9km road, which leads to important Huai Mae Sariang watershed. After about a month, I set 10 cameras along the road and nearby mineral licks. Tigers, leopards, elephants, gaur, sambar, serow, common muntjac, civet cats and porcupines made an appearance.

At one camera, four different leopards, three in yellow phase and one in the black phase, were camera-trapped. The next month, a mature leopard was caught at midday, and after that, a huge male tiger (shown in the main photograph) was captured on film. The road is now used mainly by wild creatures and forest rangers on patrol and in many places, the forest on either side has grown together.

The DNP should be commended for cleaning up the park while the road was closed. At Ban Krang ranger station alone, they collected hundreds of rubbish bags full of trash thrown into the bush by visitors.

The department has also set new regulations for visitors. Other than the headquarters area down the mountains, camping is allowed only at Ban Krang. Only day trips to Phanern Thung and Thor Thip waterfalls are allowed, and a forest ranger must accompany the visitors.

Without doubt, these measures will help Kaeng Krachan’s natural ecosystem. Due to the recent heavy rains, the park is closed once again until the beginning of the dry season next month.

These camera-trap programs have barely scratched the surface of the park’s full potential. There are still many species that surely survive in the interior. Further research and surveys should be carried out by the department to determine the diversity of this great forest.

Photo captions: The tiger, the leopard and the Fea’s muntjac are just a few examples of predators and prey that venture out on the park’s road while it is closed to tourists. Since last year, violent storms have torn up many sections of Kaeng Krachan’s main road, cutting human access to the forest’s interior.

Khlong Saeng: The Lost River

One of the Kingdom’s top wildlife sanctuaries still harboring many endangered but classic Asian animals

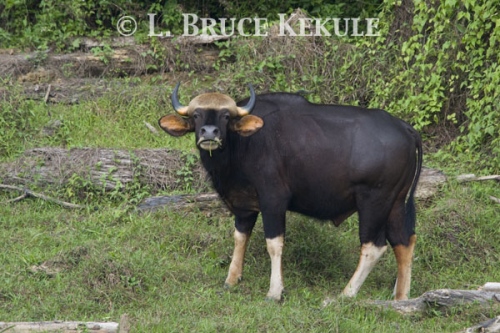

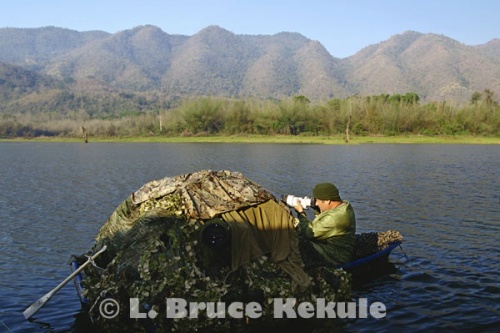

The weather is mostly clear as the sun drops behind a huge cloud close to the horizon. Light monsoon rains have begun at the end of April but hang in the mountains to the west. It has been a scorcher and heat from the day lingers over the reservoir. The light is soft and warm. About 6pm, a small herd of gaur drift out of the forest to drink at the waters’ edge and forage tender new grass. In a boat-blind about a kilometer away, I silently motor the craft closer using a battery operated trolling motor. The timing is perfect as I move in for a shot of Thailand’s magnificent but endangered wild ox.

Gaur cow in late afternoon light in Khlong Saeng

As I get closer, a mature cow feeding on an island in the lake sees something moving 100 meters offshore, and swims across to the mainland to investigate, all the time keeping her eyes locked on the strange anomaly moving in the water. Water drips from her underbelly, and her reddish-brown coat and deeply curved horns standout in the late-afternoon magic. I fire off a salvo of images hoping my camera and lens will capture this beautiful creature so late in the day. For a few brief moments, the old cow showcases Thailand’s natural heritage.

Young gaur bull

There are many beautiful forests in the South, but one in particular is truly a tribute to nature. Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary was once a magnificent natural watershed that provided water throughout the year to the inhabitants of the lowlands on the east side of the Thai Peninsula. It still harbors some very impressive animals such as elephant, gaur, tapir, serow, sambar, clouded leopard, sun bear, Great Argus (second largest of the pheasant family in Thailand), and the mighty king cobra – and the list goes on.

Gaur calf

Royal Decree encompassing 1,155 square kilometers of dense forest established Khlong Saeng in 1974. The sanctuary is the biggest in the Khlong Saeng – Khao Sok Forest Complex totaling more than 5,316 square kilometers and incorporating 12 protected areas, 11 of which are terrestrial and one with offshore islands in the Andaman Sea. Its forests are predominantly moist evergreen and most of the plants and animals are of Sundaic origin with some Indochinese species interspersed.

Curious gaur cow

Situated in the provinces of Surat Thani, Phang Nga, Ranong and Chumphon, the complex includes: Khlong Saeng, Khlong Yan, Khlong Naka, Khuan Mai Yai and Ton Pariwat wildlife sanctuaries, and Khao Sok, Kaeng Krung, Lam Son, Sri Phang Nga, Khao Lampi – Hat Thai Muang, Khao Lak – Lam Ru and Khlong Phanom national parks. They are under the responsibility of the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department (DNP) to provide protection, management and staff.

Gaur in the late afternoon

Khlong is the southern Thai word for a tributary or canal. The main tributaries of the Khlong Saeng valley include the Saeng, Ya, Yan, Ake, Mon, Ye and Mui that made-up the mighty Khlong Pasaeng. This river ran wild from the Phuket Range down to the Mae Tapi River in Surat Thani and eventually into the Gulf of Thailand. The riverine habitat teamed with flora and fauna, and the ecosystem was absolutely pristine. Tigers and leopards lived alongside many prey species like sambar, muntjac and wild pig. Elephants and gaur were fairly common. It was a magnificent wilderness at one time.

Gaur cow and her calves

But in the mid-1980s, a drastic change to the Pasaeng River was to come about. To increase Thailand’s electrical power needs, and back when building hydroelectric dams was in vogue, it was decided by the Electrical Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT), a state enterprise, and the government, to construct the Rajaprabha Dam that eventually inundated a total of 165 square kilometers (65 sq. miles) of the Khlong Saeng valley to become the Chiew Larn reservoir in 1986. The water body extends into the sanctuary for more than 50 kilometers (30 miles) but is only about two kilometers at its widest point.

Flooded forest in Khlong Saeng

Where rivers and forest previously existed, large waterways now provided easy boat access to virgin wilderness. The skeletal forms of what were once huge forest trees stand as a reminder of what disappeared beneath the flood more than a quarter of a century ago. Some trees still stand but many have come crashing down especially up-stream where decaying is severe. Millions of plants and animals perished as the floodwaters rose. The late Seub Nakhasathien, one of Thailand’s hero’s of wildlife conservation plus rangers and wildlife researchers saved hundreds of stranded fauna caught on islands. There are some 160 of them scattered throughout the reservoir when water levels are low. Some denizens were able to swim and move to higher ground but not all. It was the beginning of a new ecosystem – a large lake with a very long and complicated shoreline.

White-bellied sea eagle with a fish

Probably the most impressive scenic site in the sanctuary is the massive limestone ‘karst’ formations that were formed sometime during the mid to late Permian over 200 million years ago. It was a time of widespread mountain-building and volcanic activity. Thailand was part of Gondwanaland that was still attached to Pangaea, the ‘Supercontinent’. These colossal outcrops, some reaching as high as 960 meters (3,150 feet), look almost ‘architectural’ in design and are as impressive as the famous towers in Phang Nga Bay to the south. These configurations are the remnants of a prehistoric coral reef that once thrived here.

King cobra hunting for prey

Of all the animals in Khlong Saeng, gaur is probably the icon of wildlife in the sanctuary. These bovid are now rare in Thailand surviving only in a handful of protected areas, but they thrive fairly well. However, this only occurs around the upper reaches of Khlong Saeng and several other tributaries. The population of gaur here is estimated to be about 100 individuals and is one of the Kingdom’s best reserves for the species due to the dense moist evergreen forest.

Osprey in the mid-day heat

Breeding seems to be healthy; as many calves and young gaur of various ages have been seen in several herds I photographed at this site. Large solitary bulls keep the herd in stable breeding condition. These herbivores need huge tracts of forest free of human presence to survive. Being extremely shy, these wild cattle flee on the first sign of man. Good availability of food, water and minerals are important to their survival and the sanctuary provides these in abundance. There are still some elephants but their numbers seem to have declined. Further downstream, human activity has all but obliterated the large mammals including the tiger, which has not been seen for more than twenty years, even after extensive camera-trap surveys carried out by the research unit at the sanctuary headquarters.

Young Asian Tapir camera-trapped

Next door to Khlong Saeng is Khao Sok National Park covering 739 Square kilometers established in 1980. Khao Sok is well known around the world. The national park’s mandate in Thailand is to promote and encourage tourism into various nature sites within the protected area. After the Rajaprabha dam was completed, boats and wooden rafts were built at an alarming rate to accommodate this new business of boating visitors into the lake. Now there are hundreds of craft, many extremely noisy. Fishing was allowed and it was a free-for-all in the beginning with everyman for himself. All forms of fishing were used including explosives, electricity, nets, trap-lines and spear guns. Many areas were quickly depleted of fish, and fisherman must now venture deeper into the reservoir trying to eek out a living.

Old bull gaur camera-trapped

Actually, the Fisheries Department (FD) has a regulation in place that states ‘no fishing’ is allowed from the dam five kilometers to the limestone cliffs during the breeding season from 15th May to 15th September. This ban should extend completely into Khlong Saeng. Unfortunately, there seems to be little or any formal protection in place as boats and people come and go with no restrictions. Also, in Khao Sok, there are many rafts that have extensive facilities including a ‘karaoke’, which seems distant from nature. Every year the FD releases several species of fish into the reservoir. The ‘giant catfish’, a species found in the Mekong River, was released here and are most likely competing with other large resident fish. The FD has banned its capture but all fish are being caught for the pot, or sale to waiting ice vendors at the dock.

Dusky langur on a stump

However, a more serious problem exists that needs immediate attention before it is too late. When the Rajaprabha hydroelectric dam was finished and working on-line, EGAT passed a regulation and transferred protection duties to Khao Sok National Park. This included the complete waterway and 100 meters up into the terrestrial landscape meaning the entire water body intrudes deep into Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary for more than 50 kilometers and the mandate for its use and protection is controlled by the national park. People easily penetrate Khlong Saeng to poach, gather and fish, and the sanctuary officials have no authority on the waterway. Budgets are low and therefore, protection and enforcement is minimal. It is an extremely large loophole that needs to be fixed soon!

Gaur cow feeding on grass

EGAT, DNP and FD should join forces to find a viable solution, and take corrective steps to re-zone the reservoir. The solution is easy. About 20 kilometers into the lake at the mouth of Khlong Mon, the lake narrows down to about two hundred meters across. A rope barrier and guard post has been erected by the sanctuary but is unmanned for the most part due to the national park’s mandate. Constant overfishing and visitation to the upper reaches of Khlong Saeng over the long run will definitely have a serious impact on this sanctuary, especially gaur due to their very shy nature. Another very sensitive species is the Great Argus. These beautiful birds will abandon a breeding site if disturbed by humans. There are six hornbill and two gibbon species indicating a pristine forest. Stump-tailed macaque is the largest primate and dusky langur or leaf-monkeys are common. White-bellied sea eagle, lesser fish-eagle and osprey plus otters depend on fish and even though there is still some species in abundance, saturation fishing will eradicate most fish over time.

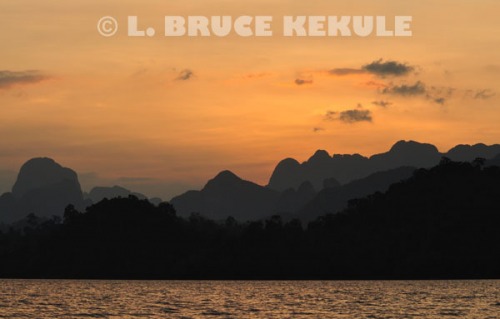

Sunset over the Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

The DNP’s mandate for ‘wildlife sanctuaries’ is straightforward; they have been set aside for wild species propagation, biodiversity research and habitat preservation. With hundreds and possibly thousands of people visiting Khlong Saeng every year, it is doubtful whether the sanctuary can sustain its habitat diversity over the long term. Also, trash and oil pollution from the boats is serious problem that needs attention and constant surveillance.

Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary is a beautiful but forbidding forest, and its incredible biodiversity it a tribute to the Kingdom’s natural heritage. In terms of research, very little is actually known about the interior but its future depends on many things. Most of all; the protected area should become the focus of attention so that all concerned may take a hard long look and save it for the future. Decisive and quick action in the only recourse before it is too late.

In the field:

After more than a decade of visiting forests in the East, West and North, I decided it was about time I went down South. From January 2009, I began a photographic and camera-trap program in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary. Over the course of five months, a trip every month was scheduled. On the very first outing, we arrived at our final destination after a four-hour boat ride. I jumped onto a floating raft (ranger station) not far from the headwaters of the Khlong Saeng. After a few minutes of unpacking and getting settled in, someone shouted out that an elephant was by the waters’ edge across from the ranger station in plain sight.

Young tusker elephant in Khlong Saeng

What a strange bit of luck. We immediately jumped back in the boat and crossed over to where a young tusker was feeding on bamboo leaves and occasionally taking a drink from the lake. He was alone and we could not figure out why. Possibly the herd bull or an old belligerent cow elephant had pushed him out. We will never know. This little bull was in good condition and looked fine. The next day, I was back at the same spot waiting but he did not show. The morning after, he was back. I left the next day but before we parted company, I decided to name him ‘Nong Saeng’ after the river. I thought that would be the last time I would see the little youngster.

Young bull gaur

A month later I was back at the station and the first thing I asked; where was ‘Nong Saeng? No one had seen him. Two days later about 4pm while I was traveling up-river in my boat-blind, I bumped into him again, but much farther into the reservoir. He was back by the shoreline feeding and I was elated to say the least. I stopped the boat and had a great time photographing this lively young elephant once again. He was seen a couple more times by the rangers but since then, ‘Nong Saeng’ has probably gone up into the hinterland as the monsoon rains have begun. This encounter will always create fond memories of nature’s little quirks and how things work out sometimes. Hopefully, I will get a chance to see him again next year in January when I return to continue documenting the wildlife at Khlong Saeng.

Khao Ang Rue Nai – Natural splendor in the East

Thailand’s largest remaining tract of lowland evergreen rainforest and a very important wildlife sanctuary

During mid-morning at a secluded murky stream deep in the Eastern evergreen rainforest, a single reptile glides effortlessly through the water to a favorite basking spot. Lying on the bank some three meters long, this freshwater Siamese crocodile warms-up in the bright sunlight. Judging from the many photographs taken of this individual, it is a mature animal. Sex and actual age are not known, but it has been here for sometime now. The habitat consists of several connecting deep ponds with abundant fish stocks. The crocodile takes occasionally small mammals and birds. It is a lucky but lonely survivor.

Sunrize in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

During mid-morning at a secluded murky stream deep in the Eastern evergreen rainforest, a single reptile glides effortlessly through the water to a favorite basking spot. Lying on the bank some three meters long, this freshwater Siamese crocodile warms-up in the bright sunlight. Judging from the many photographs taken of this individual, it is a mature animal. Sex and actual age are not known, but it has been here for sometime now. The habitat consists of several connecting deep ponds with abundant fish stocks. The crocodile takes occasionally small mammals and birds. It is a lucky but lonely survivor.

Little grebe in the reservoir

Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary is home to probably the last truly wild Siamese crocodile in eastern Thailand. There are just a few surviving in nearby Cambodia but their future is threatened by the construction of hydroelectric dams. Since Siamese crocs can live for 60-70 years, it is hoped this individual will be in Khao Ang Rue Nai for some time to come.

Bull elephant at a waterhole

Kitti Kreetiyutanont, a forest official working in the sanctuary, recorded the first sighting of this individual in 1987 by photograph. The croc still survives to this day, and is a tribute to the tenacity and longevity of the species. However, it is a case in point where humans are to blame for the disappearance of these remarkable creatures, from the lowlands all the way up into the forest; by encroachment, poaching and logging that went on for decades.

Bull elephant on the move

Some 230 million years ago judging from fossil evidence, the first crocodilians evolved from the Archosaur. Crocodiles have outlived the dinosaur but here in Thailand, the demise of the wild species is close at hand. In the past, crocodiles were found in just about every main river system throughout the Kingdom. Modernization has brought these mystical creatures to the brink of extinction. They were mainly captured to stock crocodile farms, and were also killed by the people who mostly feared the sometimes aggressive reptiles. With no laws in place at the time to protect these animals, extinction was imminent.

Banteng herd at a waterhole in Khao Ang Rue Nai

However, a very small reintroduction program could be implemented here, and with increased protection, could work to save the remarkable Siamese crocodile from extinction in the wild. There are several other sites that can also be used for reintroduction such as Yot Dom National Park in Ubol Ratchathani province, and Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary in Chaiyaphum province where crocs were once common. There are thousands upon thousands of crocodiles in farms, mostly by crossbreeding and hybridization. A wild population is the only option. A few of the crocodile farms still have

Banteng herd at a waterhole

Siamese crocodiles taken from the wild and could easily start a program to save the species. There has been one attempt at a national park to release crocodiles but it apparently was abandoned. Also, several Siamese crocodile have mysteriously showed up at Khao Yai and Thung Salang Luang national parks and believed to have been released clandestinely. These crocodiles should be captured and DNA checked to see if they are truly wild crocs.

Banteng cow with a lame right rear hoof

Khao Ang Rue Nai is situated in the provinces of Chanthaburi, Prachin Buri, Chachoengsao, Chon Buri and Rayong. The sanctuary headquarters is located about three hours drive from Bangkok and was established in 1977 by Royal Decree. The protected area consists mainly (80 percent) of dry-evergreen forest with moist and hill evergreen, dry dipterocarp and mixed-deciduous forests interspersed with many streams, and are eastern Thailand’s largest remaining tract of lowland evergreen rainforest in the country. An annual rainfall of some 3,000 to 4,000 millimeters (118-160 inches) has been recorded.

Mother elephant and infant

The sanctuary is 1030 sq. km (398 sq.miles) in area and is part of the Prachinburi floodplain. It is the largest protected area of the Eastern Forest Complex, which includes four national parks and three wildlife sanctuaries: included are Khao Chamao – Khao Wong, Khao Khitchakut, Namtok Phlio and Khlong Kaeo national parks, and Khao Soi Dao, Khlong Khrua Wai Chaloem Phrakiat and Khao Ang Rue Nai wildlife sanctuaries. Unfortunately, these protected areas are mere islands in a sea of humanity.

Burmese reticulated python

In the old days, the Eastern Forest Complex was known as the Phanom Sarakham forest, and was one of the richest forests in Thailand famed for its abundant flora and fauna covering an area of about 8,000 square kilometers. Just a short 50 years ago, this dense, lush and vast jungle was home to large herds of elephant, gaur and banteng. Tigers and Asian wild dogs were common as were most of the smaller mammals like sambar, serow, wild pig, and muntjac (barking deer). Hornbills and gibbons, indicator species of an intact forest, thrived. But that quickly shrank as the human population expanded in causing irreversible damage to the ecosystems.

Variable squirrel

Due to its close proximity to Bangkok and other cities, many city hunters entered this forest at night spotlighting, either on foot or by jeep. This decimated the wildlife as everything was taken without regard for species, sex or age. The most damaging was the eight 30-year logging concessions carried out by logging companies that cut many roads into the forest. This alone-allowed easy access to virgin forest and it was not long before most everything vanished. In the meantime, this wilderness was also completely surrounded by agricultural land, which also took its toll.

Crab-eating macaque eating ‘mama’ dried noodles found in a trash can

Fortunately, and before it was too late; enough forest was saved so that the mammals and others were able to survive to the present. Although populations of the large herbivores have declined, they can be still be seen at various sites within the sanctuary. Unfortunately, the tiger has disappeared but a few Asian wild dogs still roam the interior and are at the top of the food chain.

Lessor whistling ducks

In 1967 when the Vietnam War was in full swing, the government cut many new roads through the forests in eastern Thailand supposedly to facilitate movement of US personnel and equipment from Utapao Airbase to other airfields in the Northeast. At the end of the Cambodian civil war in 1986, the Thai Army made one such road through the top half of Khao Ang Rue Nai. The impact of the road on this forest and the animals has been devastating and many creatures have been killed or maimed by vehicles on this thoroughfare.

Lessor whistling ducks

The research unit stationed at Khao Ang Rue Nai on road-kill, deer and bovid population, elephant management and jungle fowl has carried out much research. Most accidents happened from 6pm to 6am. After much publicity, the road is now closed from 9pm to 5pm everyday and road-kill has dropped 70-80 percent. This is a plus for conservation where like-minded people have taken action to help prevent further carnage of wild animals.

Lessor whistling ducks

A total of 132 mammal, 395 bird, 32 amphibian and 107 reptile species have been recorded. Thousands of plant and insect species are found. Birds such as the black-and-red broadbill and the Siamese Fireback thrive. The rare woolly-necked stork and lesser adjutant once lived in these forests but have not been seen for sometime and are presumed extinct locally.

Oriental darter

Rare water birds like the Oriental dater and great cormorant migrate here and stay for several months at a reservoir built near the headquarters. This water source was created for the elephants during the dry season hoping to help eliminate human-elephant conflict. The marauding giants in search of food and water have killed and hurt many people. There are also recent reports of foraging gaur attacking farmers outside the sanctuary by mostly young bulls kicked out of the herd.

Oriental darter

The dangers facing Khao Ang Rue Nai are now severe as poachers and farmers snare indiscriminately. Cheap and simple rope snares have killed many elephants, gaur and banteng plus many other mammals. The villagers say they are protecting their crops. But many areas are in close proximity to the forest and interaction between wild beast and humans is a serious problem for the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department, who are constantly under pressure from these conflicts. More personnel and protective management plus a bigger budget are needed to protect these forests.

Great cormorant and little cormorant

Great cormorant

Little cormorant

But it must also be understood by the general public that wildlife sanctuaries are not open to the general public and have been set aside for species conservation, protection and bio-diversity research. Unlike national parks, recreation is not encouraged although it does occur, especially at waterfalls and viewpoints. Needless to say, the future of all conservation areas in the Kingdom is in the balance, and only increased protection, conservation awareness and education are the keys to sustain Thailand’s wonderful natural heritage.

Notes from the field:

For capturing images of such elusive creatures like crocodiles and elephants, infrared camera-traps are a very productive alternative to endless days of sitting in a hot photo-blind. Crocodiles are creatures of habit, so I set a camera-trap at its favorite basking spot by Klong Takrow. The croc was caught on film many times during a two-week session. One frame shown above was taken in early morning light. It seems as if the crocodile is smiling, and saying, “I’m right here”. I was elated to get such a lucky shot.

Siamese crocodile camera-trapped at Klong Takrow

Khao Ang Rue Nai is currently home to about 130 wild elephants. The road transects the northern part straight through old elephant habitat. The narrow road was widened and resurfaced allowing faster speed. In 2002, a man and woman in a pickup truck barreling through the sanctuary at high speed did not see the elephants on the road until it was too late. The truck crashed head-on into a 5-year-old tusker. The truck’s driver was killed on impact but the woman survived. The young elephant died shortly after.

The ironic circumstances of this accident – ancient animal and modern machine – weighed heavy in my heart. I had set camera-traps near the crocodile pond in the sanctuary a couple of weeks before. When the film was retrieved and processed, I was elated that a herd of elephants had triggered one of the cameras producing several frames. One frame showed an inquisitive little tusker looking straight at the camera. My elation quickly subsided a few days after the terrible news on TV and newspaper reports that a small tusker had been killed in the sanctuary. My worst fears were confirmed after consultation with Royal Forest Department officials and comparing photographs. A scar on the dead calf’s forehead proved it to be the same animal that I had ‘camera-trapped’.

Such accidents are a terrible blow to the conservation of Thai elephants, because tuskers are particularly vulnerable, being subject to hunting for their ivory. This young tusker was not the first and probably not the last elephant killed by reckless driving on this road. However, the Royal Thai Army and the Department of National Parks should be commended for taking the initiative by partially closing the road at night.

It is hoped that one day the time will be extended from 6pm to 6am to increase the animal’s chances for survival. This is the logical step and humans using this road would have to adjust to the new times for the sake of saving the wildlife.