Posts Tagged ‘Thailand’s natural heritage’

THAILAND’S NATURAL HERITAGE: A look at some of the rarest animals in the Kingdom – Part One

FRONT JACKET – A young goral kid in Doi Inthanon National Park near the summit of the Kingdom’s highest mountain in Chiang Mai province, Northern Thailand.

BACK JACKET – The Emerald Pool in Khao Phra Bangkram Wildlife Sanctuary in Trang Province, Southern Thailand, and home to the rarest bird in Thailand; the Gurney’s Pitta.

INSET: BACK JACKET – The Gurney’s Pitta in Khao Phra Bangkram Wildlife Sanctuary. Unfortunately, as of this posting, these wonderful avian creatures are now officially extinct in Thailand. Some may be lingering on in nearby southern Myanmar (Burma).

FRONT ENDPAPER: Thailand 130 million years ago.

BACK ENDPAPER – Sunset and lightning in Kaeng Krachan National Park, Phetchaburi province.

THAILAND’S NATURAL HERITAGE

Page 2-3

Common Shelduck in Bueng Boraphet Non-hunting Area in Nakhon Sawan province. This duck species is a rare winter visitor.

Page 4-5

Green Bee-eaters at sunset in Mae Hia Agricultural Research Station in Chiang Mai province. These colorful birds are found in many parts of the Kingdom. They feed on bees and other insects caught in flight by hawking.

CREDIT PAGE

Published in 2004:

WKT Publishing Co., Ltd

102/32 Soi Ronnachai, Setsiri Road,

Phayathai, Bangkok 10400, Thailand

Tel:(66-2) 619-6774 Fax:(66-2) 619-6775

e-mail: lbkekule@mac.com

website: www.brucekekule.com

Distributed in Thailand:

Asia Books Co., Ltd

5 Sukhumvit Road Soi 61

Bangkok 10110, Thailand

Tel:(66-2) 715-9000, 714-0740

Fax:(66-2) 381-1621, 391-2277

e-mail: purchase@asiabooks.com

website: www.asiabooks.com

Photography, text & design:

Copyright © 2004 L. Bruce Kekule

Consulting Editor:

The late Hardy Stockmann

Text Editors:

Ben Davis

Jim Pollard

Proof Editor:

Pongpet Mekloy

WKT Publishing Directors:

Puangpayom Kekule

Marguerite Dalal

Tipp Dalal

Paper supplied:

Advance Agro Public Co., Ltd

Bangkok, Thailand

Reproduction & Printing:

2004 – 1st Edition: Sirivatana Interprint Public Co., Ltd, Bangkok, Thailand

2006 – 2nd Edition: Phongwarin Printing Ltd. Bangkok, Thailand

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying recording or otherwise, without prior permission from:

WKT Publishing Co., Ltd

For information about reproduction, contact WKT Publishing Co. Ltd

ISBN — 974-92327-7-1

Page 6-7

A Gaur bull entering a mineral deposit in Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary in Kachanaburi province along the western border with Burma. They are the largest bovine in the world standing 1.7 meters at the shoulders and large mature bulls can weigh close to a ton. These even-toed ungulates are very shy.

Contents

Foreword 9

The Creatures of Nature 10

Thailand’s Mesozoic Vertebrates 52

Submarine of the Jungle 68

Vanishing Asian Giants 80

The Brink of Extinction 90

The Lonely Crane Incident 100

Wildlife Candid Camera 114

Goats in the Mist 128

Deer in Jeopardy 144

Bulls, Cows and Calves 160

Big Cats in Kaeng Krachan 180

Carnivores of the Phetchaburi River 198

Perils of Wildlife Photography 208

Wildlife in Danger 218

Bibliography 223

Photograph Index 224

Acknowledgements 227

Page 8-9

Sunrise at Mae Lao – Ma Sae Wildlife Sanctuary in the northern province of Chiang Mai. Mon Liem, a granite massif in the northern part of the sanctuary is home to a small herd of goral. Other rare creatures like the Hume’s pheasant, Ultramarine flycatcher and Asian Wild Dog thrive here.

Foreword

Thousands of plants and animals will become extinct in the 21st Century. The world loses some 60,000 species every year to extinction. This situation is unacceptable and unforgivable.

Persistent human encroachment into wilderness is a prime reason for this tragedy. As the human population explodes, expansion into protected reserves is nearly unstoppable. Interlopers takeover land where wild animals live. Forests are transformed into tourist attractions, agricultural land, golf courses and resorts. Wildlife disappears forever.

The importance of protecting and saving the Kingdom’s remaining forests and wildlife is critical. The key to success in preserving nature is to create awareness at all levels of society. Do your part to help Mother Nature and she will reward you.

L. Bruce Kekule

Thailand – 2004

The Creatures of Nature:

An introduction to the Kingdom’s natural history

Page 10-11

Forest Crested Lizard in Sai Yok National Park. These beautiful ground dwelling reptiles are common here, and hunt earthworms and other creatures in the leaf litter.

Life has been evolving on earth for thousands of millions of years. Evolution is the supreme mechanism which continues relentlessly. New species are created by natural selection, Darwin’s chilling insight. Cataclysmic changes are a regular occurrence on Mother Earth.

For all of its ability, intelligence and technology, the species Homo sapiens still remains largely powerless against the forces of nature. Lightning, volcano’s, hurricanes, cyclones, tornados, floods, typhoons, drought, earthquakes and meteor strikes are uncontrollable and unstoppable by any means. As the planet passes through time, natural selection will inexorably generate new species.

Mother Earth hosts a truly wondrous array of animals and plants, each with its own niche. Some have taken to the air, some to the land and many stayed in the sea. Insects, make up three-quarters of all living species and are the most numerous of nature’s creatures. There are said to be 200 million insects for every human being.

Page 12-13

Goral in Doi Inthanon National Park. These goat-antelope can be seen around ‘Kew Mae Pan’ Nature Trail close to the summit of Doi Inthanon, Thailand’s highest mountain. A small herd of goral still survive in the park.

Today several million species survive on the planet. Hundreds of thousands have become extinct. The dinosaur, surely the most exciting in the popular imagination, survived for over 160 million years before succumbing to the law of survival of the fittest.

To properly showcase the beauty of Thailand’s natural heritage, we need to return to the beginning of life. Earth is now thought to have started evolving about 4,550 million years ago (mya). Because sedimentary rocks have not been found from the first 800 million years, the earliest life forms are lost in the geological record. All that can be said for sure, Earth was an extremely inhospitable place during this time of evolutionary change.

Page 14

Elephants camera-trapped at a mineral deposit in Kaeng Krachan National Park in Phetchaburi province. The park is about two hundred kilometers southwest of Bangkok. The forest and its biodiversity is still fairly intact, and the park supports about 200 wild elephants.

During the Archaean eon (4,550-2,500 mya) very primitive life forms appeared and by 3,500 mya began to photosynthesize and increased oxygen in the atmosphere. These first life forms were single-celled creatures known as cyanobacteria (blue-green algae).

The Proterozoic eon (2500-543 mya) brought dramatic changes to Earth. At the beginning of this eon, the only living things were bacteria, but by its end there were multicellular plants and animals, all in the sea. Together, the Archean and Proterozoic known as the Precambrian or ‘hidden life’ taking up 90 percent of Mother Earth’s time clock.

The Phanerozoic eon followed and is also known as ‘visible life’ including the Paleozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras. This eon has produced multi-celled organisms that have dominated life on earth.

Page 15

Gaur bull entering a mineral lick in Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary along the western border with Burma. They are the largest bovine in the world standing 1.7 meters at the shoulders and can weigh close to a ton. These even-toed ungulates are shy and hard to see in the forest due to acute senses of hearing, smell and eyesight, and this bull is in his prime.

In early Archean times, a huge global ocean covered most of the planet. Earth’s first continents were small and evolved from volcanic rock. These islands assembled into proto-continents on tectonic plates that moved across the globe. Continental fragmentation and reassembly took place, and ancient outlines are not certain.

These early continents came together into one and at the start of the Triassic period, Pangea the ‘supercontinent’ formed with Laurasia in the north, and Gondwana in the south. There was only one ocean; Panthalassa. Pangea stayed stable throughout this period but by Early Jurassic, began breaking up. By the end of the Cretaceous, the continents assembled into the world we know today.

Earth during the Triassic Period

Thailand is formed by two continental blocks that drifted from Gondwana during the Late Devonian-Carboniferous and then collided joining together in the Late Permian-Triassic. The ‘Indochina’ block is in the east, and the ‘Shan-Thai’ or ‘Sibumasu’ block is in the west and peninsula. These two blocks drifted north and then eventually collided with what is now South China in Late Triassic-Early Jurassic.

Southeast Asia and its continental blocks

Many mesozoic vertabrate fossils have been discovered in the Kingdom found mainly on the Khorat Plateau in Khon Kaen, Kalasin, Chaiyaphum and other northeastern provinces. Sauropod dinosaur fossil bones have recently been discovered in the northern province of Phayao and Krabi in the south. Cenozoic fossils have also been unearthed in abundance from lignite mines in the Krabi basin and the northern provinces of Lamphun, Lampang and Phayao.

Page 16

Banteng at a water hole in Huai Kha Khaeng. This mature bull was chasing after a herd during the breeding season. He was very alert for any sign of predators like leopard, tiger or wild dog, and did not stay long. A quick moment in the life of Thailand’s beautiful wild cattle that have become quite rare due to poaching pressure and encroachment.

An enormous array of animals still survive in the Kingdom. Thailand’s geographic position in the heart of Southeast Asia and its varied habitats have gifted the country with an astonishing wealth of biological diversity. The country possesses many different types of wilderness, from seabed to coastal mudflats, from mangrove swamps and lowland evergreen rainforest to montane evergreen pine forest. Luckily, the country’s flora and fauna is well documented.

The Kingdom has recorded some 289 species of mammal, over 1000 bird species, 313 reptile and 107 amphibian species, and many thousands of insect and plant species. An infrastructure of more than 207 protected areas divided into national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, non-hunting areas, and marine parks guard these rich natural resources. The magnificent Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuaries in the west have been bestowed World Heritage Site status by UNESCO in recognition of their biodiversity in wildlife. The eastern Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Cpmplex is now also a World Heritage Site as of 2005.

Page 17

Wild Water Buffalo in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. This young bull was part of a herd of twelve buffalo that just visited the river to drink and cool off during the mid-day heat. They are quite rare with about 50 individuals surviving in this World Heritage Site.

The world’s smallest flying mammal, Kitti’s hog-nosed bat, lives in caves along the western border with Burma. A miniature nocturnal animal no bigger than a human thumb, it is also known as the ‘bumblebee bat’. Sadly, Kitti’s hog-nosed bat is critically endangered because of encroachment and capture for the illegal trade in stuffed animals sold along the streets in cities that have tourists.

On the other end of the spectrum, the Asian elephant is, Thailand’s largest terrestrial mammal. These giant creatures prefer to live in deep forest far away from human beings. The wild elephant have declined over their range and it is estimated that 2,000 or more remain in the larger national parks and wildlife sanctuaries.

Some 2,600 domesticated elephants live throughout Thailand. Unfortunately, many are abused for the sake of money. Some of these poor creatures are paraded around by their mahouts at tourist centers and major cities selling food to be given to the elephants to make merit. Their future is bleak and only improved protective management can save them.

Page 18

Indochinese tiger at a hot spring in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. The tiger is the largest cat in the world and sometimes can take mammals as large as gaur and banteng. They are rarely seen in the open and have keen senses to keep them out of harm’s way. These big cars have become rare in Thailand with about 250 found nationwide.

Other mega fauna include gaur, the world’s largest bovine. These forest-dwelling oxen are dark brown to black with white or yellow stocking feet. Living primarily in evergreen forest, gaur is very shy and not easily seen apart from their hoof prints and droppings. In some protected areas gaur can be found alongside banteng, a red colored bovine which prefers open woodland and dry deciduous forest. Both species visit mineral licks to supplement their diets. In Thailand, banteng are more endangered than gaur. Fewer than 500 individuals of each species remain.

Wild water buffalo are quite rare and survive only in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary which has several small herds with no more than 50 or so individuals. Wild buffalo are much larger and fiercer than domesticated buffalo. All wild bovidae are endangered because of poaching and encroachment of habitat in the protected areas where they occur. Thailand is the only country in the world with three species of wild bovid including cattle, forest ox and wild buffalo.

Tapir, still found in the western forests down to the southern border with Malaysia, are odd-toed ungulates like rhinos. Unfortunately, neither Javan nor Sumatran rhino have been sighted for thirty to forty years. Rhino horn was and still is sought after for Arab dagger handles and for Chinese medicine. These huge beasts vanished from Thailand before any national parks and wildlife sanctuaries were established.

Page 19

Asian Leopard feeding on a sambar carcass close to a ranger station in Huai Kha Khaeng. Both black and yellow phase leopard occur here. This feline species usually feeds on the intestines and buttocks first before devouring the rest, and coming back several times to feed.

Smaller even-toed ungulates of the Kingdom include sambar, muntjac, mouse deer, serow, goral and wild pig. Goral number less than 60 individuals nationwide and are highly threatened. Found only in seven protected areas in the north. Serow still survives in limestone karst mountain areas throughout the country. Both goral and serow are prized by poachers for their meat, horns and bones.

Sambar, the largest deer in Southeast Asia, is found in some of the larger reserves. Male sambar have large multi-tined antlers. Muntjac, popularly called barking deer, is the most common cervidae species, and it still thrives in many forests. The rare Fea’s muntjac is found only in evergreen forests of the western mountains. All deer are sought after for meat, and antlers used in traditional medicine and as a trophy.

Page 20

Asian Wild Dog hunting along the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan National Park. Also known as ‘dhole’, this canine species is still surviving very well in this important watershed. They are very efficient carnivores. These dogs were caught by camera trap.

Eld’s deer and hog deer, each once very common in Thailand, is unfortunately extinct in the wild although they are being bred in captivity for reintroduction. The National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department run several programs. Both species have been introduced into Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary in the Northeast. Schomburgk’s deer was endemic to the marsh habitat of the central plains but became extinct in the 1930s due to agricultural expansion. For centuries, Thailand exported millions of deer to other Asian countries like Japan and China. That was one of the main reasons for the extinction of these deer.

One of the world’s smallest ungulates is the Greater and Lesser Oriental Chevrotain. These delicate mouse deer still live in some forests of the east, west and southern Thailand. Males have no antlers but long fang-like canine teeth much like male muntjac.

Page 21

Malayan Sun Bear in Kaeng Krachan National Park caught by camera trap. This animal is looking up into the trees for beehives or fruit, or maybe scraching it’s back. Known as the world’s smallest bear, they are identified by a u-shaped mark on the upper chest and neck. These omnivores are ferocious creatures and excellent climbers with long claws.

Tiger still survive but only in very small numbers and only in the larger protected areas rich in prey species such as deer, wild pig and wild cattle. With a massive build, powerful legs, and long muscular torso, the tiger is the world’s largest feline and the only one with stripes. The stripes are like fingerprints and thus no two tigers are exactly alike. This magnificent cat has been extremely persecuted for its skin as a trophy, and for bones and other body parts for the Chinese medicine trade. It is impossible to say exactly how many tigers still survive in the wild in Thailand but 250 is the number accepted by most experts. The future is bleak for the big cat unless its remaining habitat is fully protected.

The leopard is the second largest cat in Southeast Asia. They come in two color phases – some have a yellow coat with black spots, and the others are melanistic black. Both have spots but on the black phase, can only be seen in certain light. Still found in a few protected areas, they, like the tiger, have been hunted by poachers for their pelts and bones. The Asian sub-species are slightly smaller than the Indian or African leopard. Leopards survive better than tiger close to human settlements because they are largely nocturnal and because prey species are mostly smaller. The total population of leopard in the Kingdom is not really known.

Large Indian Civet in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. These beautifully marked carnivores feed on small animals but also eat fruit, and thrive close to villages as scavengers and poultry thieves.

Smaller cats include the clouded leopard, golden cat, fishing cat, flat-headed cat, jungle cat and leopard cat. As with the larger felines, most are now very rare, with the exception of the leopard cat that is still found in most forests. All wild cats are in serious decline due to human population growth and habitat loss.

The most social of all carnivores is the Asian wild dog, also known by the Indian word ‘dhole’. Preying mostly in large packs on large herbivores, they are very efficient hunters devouring skin, bones and all. Wild dog normally do not eat carrion like their smaller relative, the Asiatic jackal. Both species survive in many areas as long as there are prey species in good abundance. Wild dogs tend to thrive where the tiger and leopard have vanished, taking advantage of the void left by the cats’ disappearance from many forests.

Page 23

Smooth-coated Otter in Kaeng Krachan. This lone male romped about playing in the sand but did not stay for long. An old Siamese crocodile also lives here in the pond and showed up about an hour after the otter had left. A great day on the Phetchaburi River.

Two bear species are found in Thailand: the Asiatic black bear and the Malayan sun bear. Both of these omnivores have been hunted for their paws, gall bladder and bile, rendering them very endangered throughout their range. The sun bear, the smallest bear in the world at about 27-65 kilograms, has a U-shaped mark on the upper chest and neck. Black bears are considerably larger at 65-150 kilograms and carry a V-shaped mark, also on the upper chest. Both species are omnivorous, eating both plants and small animals. The bears eagerly seek bee hives and will claw trees apart for the honeycomb inside.

Page 24

Muntjac at a mineral lick in Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary in western Thailand. Also known as barking deer for the loud bark they make when a predator is detected. This male came in early morning for a drink. These small deer are still found in many forests in Thailand, but are poached mainly for their meat.

Smaller carnivores include otter, civet, linsang, yellow-throated martin, badger, weasel and mongoose. The largest civet is the binturong, which looks like a small bear. The slightly smaller large Indian civet is very beautifully marked. Four otter species are found here and the largest is the smooth-coated otter, found only in a few protected areas in Thailand. Small carnivores have been drastically reduced by loss of habitat and poaching.

Page 25

Sambar Stag at night near a guard station in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. This mature deer was a resident around this area and was seen almost every night. Male sambar is sought after for their trophy antlers and meat.

Primates started evolving in Thailand about 35 mya during the Eocene epoch, when mammalian evolution accelerated. The order Primate includes lemurs, lorises, monkeys, gibbons, apes and humans. This diverse order consists of about 13 families and some 52 genera, and is the largest mammalian order. Also known as simians or simiiforms, the sub-order Anthropoidea is comprised of New and Old World monkeys, including apes and humans.

Page 26

Sambar doe taking a drink at a hot springs in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. This ungulate lived close by and came to this water hole almost daily. These deer are preyed on by tiger, leopard and Asian wild dog.

Several fossils of flying lemur and apes have been found in Krabi, Phayao and Nakhon Ratchasima provinces by Thai and French scientists. This has changed ideas about the evolution of anthropoids in Southeast Asia.

Some scientist now conjecture that hominoid primates evolved in Asia, possibly in parallel with Africa. A faunal dispersal corridor is believed to have existed between Southeast Asia and Africa during the Middle Miocene. Homo erectus has been found both on the island of Java and in China. Many new hotly debated theories have erupted within scientific and academic circles.

Wild Pig at a mineral lick in Huai Kha Khaeng. This solitary boar had been wallowing in mud close by during mid-morning. These ungulates are still fairly common here but are poached for their meat.

A very important find by palaeontologist Dr Yaowalak Chaimanee of the Department of Mineral Resources in 2003 in a lignite mine in Chiang Muan district of the northern province of Phayao was the fossilized teeth of a hominid primate aged between 13.5 to 10 million years old. The ape was first named Lufengpithecus chiangmuanensis and is related to the orangutans but it has latterly been reclassified as Khoratpithecus chiangmuanensis, all because of an amazing new discovery in Nakhon Ratchasima.

Page 27

Asian Tapir camera-trapped in Kaeng Krachan National Park. This is the largest tapir species in the world and their two-tone coloring is natural camouflage breaking up their outline at night and even during the day in dark evergreen forest.

In 2004, a new species of orangutan ancestor about 7-9 million years old was found when fossils were dramatically uncovered on the Khorat Plateau in Nakhorn Ratchasima province and Thailand once again found itself on the world’s palaeontological map. The new ape was named Khoratpitithecus piriyai (ape from Khorat) after Piriya Vachajitpan, who played a major role in the discovery deep in the Tha Chang sandpits of Chalerm Phrakiat district. The lower jawbone and teeth have a U-shaped dental arcade similar to that of the living ape – and of human beings. This fossil dates from way before human evolution in the region began and has been found nowhere else in the world.

Page 28

White-handed Gibbon in Kaeng Krachan National Park. This primate was spotted in late afternoon at the end of the road (Kilometer 36) past Phanern Thung Ranger Station. They are still quite common around the interior of this protected area and their call in the morning as the sun comes up is magical.

Wild primates in the Kingdom include slow loris and various macaques, langurs and gibbons. Many live in the forests of some protected areas. Populations are dwindling, however, as forest habitat is slowly destroyed and unsurped by humans. The future of wild primates is grim.

Three species of gibbon live in Thailand: white-handed gibbon, pileated gibbon and agile gibbon. A ‘hybrid’ has been identified where the white-handed and pileated gibbons overlap in forest habitat in the east. If a forest has substantial gibbon populations, it usually means the wilderness is fairly intact. But some suitable forests are becoming as rare as the animals themselves as the deadly tandem of encroachment and poaching spread throughout the wild primate range.

Crab-eating Macaque troop along the Mae Nam Lo River deep in the interior of Sai Yok National Park. Also known as ‘long-tailed macaque’. They are the most common of the five species of macaque in Thailand.

Gibbons spend their entire life in the trees. Their whooping call can be heard over long distances and can erupt at any time during the day or night. Gibbons often start calling at 4:00 in the morning in some forests and they usually quiet down after mid-morning, although they will sometimes vocalize in the afternoon. Gibbons are very active as the sun rises, usually congregating in fruiting trees. The white-handed gibbon, the most common, is found in most forests while the pileated gibbon survives only in the east. Agile gibbon live in a small pocket in the south near Malaysia.

Page 30

Pig-tailed Macaque in Khao Yai National Park alongside the road near the headquarters. These primates beg for food from passing motorists which have habituated them. They come right up to the vehicle and grab food before running off into the forest. They sometimes become quite aggressive and have bitten unsuspecting people who believe they are doing good. They have very long fangs and a bite can become quite severe.

Four species of langur, also known as ‘leaf monkeys’ share the same predicament as gibbons: Phayre’s, banded, silvered and dusky or ‘spectacled’. All have slender bodies and limbs, with a tail longer than the head and torso. Langur species range widely in coloring: black, gray, dark brown to reddish with some individuals albino. Langurs are eagerly hunted for their meat, blood, and for gallstones, which are valued in Chinese medicine. These nimble acrobats live in trees but do descend to the ground to eat fallen fruit and to drink water.

Page 31 – Photo by: Saman Khunkwamdee

Dusky Langur in Khao Sam Roi Yod National Park alongside the road near the headquarters. Also known as ‘spectacled’ langur, they are found in a wide range of habitats from montane to coastal forests, and even some offshore islands in the peninsula of Thailand.

Five species of macaque are found in Thailand: Assamese rhesus, stump-tailed, pig-tailed and crab-eating. Macaques are the most common wild primate, and some species live near or even within cities, usually associated with Buddhist temples where they have become habituated. Some species live in steep limestone hills and cliffs abounding human settlements. On the road near the headquarters at Khao Yai National Park, pig-tailed macaques beg for food from passing motorists. People who feed these creatures often receive serious bites.

Large Bamboo Rat in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. They prefer secondary growth with large stands of bamboo, where they dig extensive burrows with their feet and teeth. They are often heard digging underground.

Page 32

Common Treeshrew on a wild banana blossom in Huai Kha Khaeng. These insectivores also eat spiders, fruit, seeds, buds, lizards, and even other small rodents.

Stump-tailed macaques are the largest and the fiercest of the five species, living mostly in deep forest far from humans. Males have huge fangs and can inflict terrible wounds. Primarily terrestrial, these monkeys forage for food on the ground and rarely climb trees, although they have been seen in forest canopy, most often when fleeing poachers and gunfire. Now rare in the wild, stump-tailed macaques are found only in a few protected areas.

Page 33

East Asian Porcupine in Kaeng Krachan National Park near Ban Krang ranger station. These nocturnal creatures are Southeast Asia’s largest rodent. They are still quite common in most of the top protected areas in the Kingdom.

Slow loris is the smallest of Thailand’s wild primate species. Nocturnal and arboreal, they inhibit trees of primary and secondary forest and also groves of bamboo. These cuddly balls of fur are seldom found on the ground and are renowned for their deliberate, slow hand-over-hand movement while transversing a tree branch. Slow loris can be seen at night on fruiting trees in some of the best protected areas. Sadly, these vulnerable creatures are sought after for the illegal pet trade.

Page 34

Lyle’s Flying Fox on a tree in a Buddhist temple in Ang Thong district, central Thailand. This species is rare and found only at a few places. Roosting in large colonies, they feed on ripe fruit and can wipe out a farmer’s crop in one night.

Other small mammals found include two species of pangolin: the Malayan pangolin, found all over Thailand, and the Chinese pangolin, living only in the north. Strange looking creatures with scales all over their body, pangolins look like reptiles but in fact are true mammals. (Their scales are composed of the same protein as hair or fingernails.) Pangolins are armed with a long sticky tongue and very powerful claws enabling them to ravage ant hills and termite mounds, consuming up to 200,000 ants in one meal. Being nocturnal, they spend the day curled up in a burrow. When threatened by a predator, a pangolin will wrap its tail completely around its body, locking itself into a ball. Their scales are hard enough to defeat most attackers. Pangolins are hunted for meat, and for Asian medicine and the illegal wildlife leather trade.

Greater Short-nosed Fruit Bat in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. These medium sized fruit bats are wide-ranging and have been recaptured over 90 kilometers away from one capture site. They roost in small groups.

Page 35

Horseshoe Bat in a cave close to the Mae Nam Noi River in Sai Yok National Park. These insectivorous bats survive in the thousands in this cave. Many have been persecuted by humans using nets to capture them as they fly in and out.

Rodents form the largest number of mammal species in the Kingdom. The biggest rodent is the porcupine, of which there are two species: the Asiatic brush-tailed and East Asian. Porcupines are nocturnal creatures armed with quills, used mainly for defense against predators. Quills are hair which has evolved into sharp spines. When threatened, porcupines will spread their quills, turn their back and either attack or wait for the predator to move. The quills detach easily and have caused the death of many predators. Tiger and leopard with quills embedded in their face and front paws are often unable to hunt effectively anymore and eventually die. Some big cats have reportedly become man-eaters after having fallen victim to a porcupine’s defense.

Page 36-37

Green Peafowl in Huai Kha Khaeng. These amazing birds are thriving quite well in this World Heritage Site. They are the largest, and the most beautiful birds in Thailand with their metallic green color.

Three species of bamboo rat, burrowing rodents, still survive: large, hoary and bay. Living underground in bamboo clumps, sometimes they can be heard gnawing on the roots below the surface. Sporting long and razor sharp incisors used for both eating and digging, bamboo rats are ferocious little creatures when cornered. Hunted down for the pot, bamboo rats are considered a delicacy by hilltribe people and villagers alike.

Page 38

Black-winged Stilt in Khao Sam Roi Yod. This national park is in Prachuab Khiri Khan province, southwest of Bangkok along the coast. The species nests on the ground in the mud-flats and marshy areas. The chick is only a few days old.

Asian Golden Weaver in Bueng Boraphet Non-hunting Area in Nakorn Sawan province, Central Thailand. Weavers nest in marshy areas close to paddyfields, and rear three to four young.

Page 39

Purple Swamphen in Bueng Boraphet Non-hunting Area in central Thailand. This wetland, also home to other water birds like watercock, pheasant-tailed jacana and common moorhen, is under serious pressure from humans.

Thailand hosts 28 species of squirrel and flying squirrel. Found in many different habitats throughout the country, some squirrels are nocturnal and others diurnal, some arboreal and some terrestrial. Most eat fruits and nuts, but some supplement their diets with insects and other small animals. A few squirrel species are mainly insectivorous.

The largest is the Black Giant squirrel, a shy forest species which normally haunts the forest canopy; and only rarely ventures to the ground. Other species include: belly-banded, variable, gray-bellied, Burmese and Cambodian striped tree-squirrels. Flying squirrels, mostly nocturnal, do not actually fly but rather glide from tree to tree. The largest flying squirrel is the red giant flying squirrel, found in forests throughout the country. Unfortunately, squirrels are declining in many areas as they are sought after, both for their meat and for the skin and tail which is used to make trinkets such as key chains.

Great Comorant at Laem Phak Bia in Phetchaburi province. Once common along the Kingdom’s coastlines and waterways, this species has unfortunately disappeared but show-up from time to time possibly from Cambodia. Four vagrant birds arrived at this site in 2004.

Insectivores are insect-eating mammals including treeshrew, shrew, mole, moonrat and gymnures. Most insectivores are small although the moonrat can attain the size of a domestic cat. The colugo or Malayan flying lemur, found only in the deep south near the border with Malaysia, is an arboreal insectivore with a wing-like membrane used to glide from tree to tree like flying squirrels.

Page 40

Indian Skimmer at Laem Phak Bia. This lone vagrant arrived here in 2004. It was the third sighting of this rare species in Thailand. It is thought this lonely bird came from the Irrawaddy basin in Burma.

Bats, the only true flying mammals, are distinguished by ‘hand-wings’ formed from elongated fingers with skin stretched between them. The flying fox, still found in some areas of the South, is the largest bat in the world with a wingspan of up to 1.5 meters. Bat habitat includes city buildings, orchards, forests and limestone caves. The Kingdom hosts 112 species of bat divided into two groups: the fruit bats eating mainly fruit and nectar, and the insectivorous bats which feed on amphibians, mice or smaller bats, and some eat fish.

Page 41

Ruddy Shelduck at Mae Jo Agricultural Research Station in Chiang Mai. This female arrived in late 2003. The species is a rare winter visitor to the Kingdom. Only a few sightings occur each year.

Fruit bat have large eyes, dog-like faces and short or no tails at all. Fruit bats are important pollinators of many plants including banana, durian and kapok. A group of long-tongued bats specialise in eating nectar from flowers, inadvertently collecting pollen which they transfer to fertilize other flowers.

Page 42

Japanese Sparrowhawk along the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan. The species is a winter visitor and can be found all over the Kingdom. These raptors have keen eyesight. This juvenile stayed long enough for only one shot.

Insectivorous bats have small eyes and poor sight but very large ears used both to navigate and hunt down prey using echolocation. Emitting a series of high-pitched squeaks from their noses or mouths as they fly, the sound waves striking prey or an object are reflected back to the bat’s ears, enabling them to navigate in dense forest, catch an insect on the wing, or steer safely in a cave crowded with other flying bats. Despite being an incredibly effective means of naturally controlling insect pests, all insectivorous bats have unfortunately declined as a consequence of habitat destruction, poaching for meat, and the black market trade in stuffed animals.

Page 43

White-throated Rock Thrush at Ban Krang ranger station in Kaeng Krachan. This lone winter visitor came to the national park in 2003 and stayed for many months. This male bird became habituated to humans around the camp-ground and was easily seen.

Snakes and other reptiles can be found in several types of habitats, from the northern mountains to the southern rainforests and coral reefs. The king cobra, the largest venomous snake in the world, is found in Thailand. They can grow up to almost six meters in length and their venom is a very potent neurotoxin that can easily kill humans. Other poisonous land snakes include cobras, pit vipers and kraits, among others. Extremely vemonmous sea snakes are found both in the Gulf of Thailand and the Andaman Sea. Many non-poisonous snakes also occur: pythons, water snakes, racers, keelbacks, whip snakes, to name a few. Unfortunately, snakes are persecuted because humans as a whole, have an innate fear of the slithering creatures.

Page 44

Asian Brown Tortoise along the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan National Park. These distinctive reptiles feed on plants along the river. Ticks were found all over this tortoise.

Other than snakes, Thailand is also home to several other groups of reptiles – the largest are the freshwater crocodiles, but they have disappeared from the wild save a few individuals. Water monitors still thrive as scavengers, even in the canals of Bangkok. Smaller lizards can be found in almost every habitat. Tortoises and turtles occur on land and in waterways. Sea turtles come ashore in southern Thailand to lay eggs. But like in other parts of the world, these ancient reptiles are in serious decline.

Page 45

Hill Frog in Sai Yok National Park. They are predators of insects and other small creatures along forest streams. Amphibians started evolving on Earth about 330 million year ago.

Masters of the air, birds make up a large portion of wildlife. With over a thousand species recorded, bird-watching is very popular in Thailand. In fact, the Kingdom is one of the top birding destinations on the planet.

Page 46

Common Forest Skink along the Mae Nam Lo River in Sai Yok National Park. These reptiles forage for insects and other small creatures amongst forest litter. They are preyed on by snakes and larger lizards.

Insects number in the thousands and is the largest group of animals in the world. They are found in every habitat except the sea. Some insects are pests and raise havoc with agriculture, households and everyday life. Some are eaten and others exterminated. But they are facinating creatures evolving around us. Some need protection just like the plants and larger animals.

Page 47

Green Pit Viper devouring a skink in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. Pit vipers are equipped with heat-sensitive organs to help them locate prey. Their fangs fold back against the roof of the mouth except when they strike. Can be deadly to humans if a bit is inflicted far from medical care and is not taken care of quickly.

The Kingdom of Thailand is truly a remarkable place, and its biodiversity second to none. It is hoped the Thai people will make wildlife conservation a top priority. More emphasis should be placed on protecting the remaining wilderness areas and creatures living within. As the human population expands and natural habitat shrinks, the future hangs in the balance. Only quick positive action by people can avert the disappearing beauty we once took for granted.

Page 48

Blue Crested Lizard in Salak Phra Wildlife Sanctuary, western Thailand. These colorful lizards are abundant and hunt insects on tree trunks. They change color when alarmed.

Rhinoceros Beetle in Salak Phra Wildlife Sanctuary, Kanchanaburi province, western Thailand. These insects are found in elephant dung, which is their main diet. They also lay their eggs in dung.

Cruiser Butterfly along a forest stream in Sai Yok National Park. These invertebrates have three body segments, antennae, three pairs of legs and one or two pairs of wings.

Page 49

Bird-eating Spider in Sai Yok National Park. They prey on insects, small birds, rodents and bats. Arachnida started evolving on earth more than 380 million years ago. Spiders are not insects but many people misunderstand this. They have two body segments and four pair of legs but there are a few six legged spider species.

Damselfly in Salak Phra Wildlife Sanctuary, western Thailand. These delicate creatures are usually found along forest streams where they perch on plants or rocks until they have spotted their insect prey.

Page 50

Dragonfly in Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary close to Burma. These winged predators have been on Earth for some 320 million years from the Late Carboniferous. This one has a striking color pattern like a tiger and was about 2.5 inches long.

Common Rose and Dark Blue Tiger butterflies on the road in Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary. They are attracted to urine left by large mammals like muntjac, sambar and gaur.

Page 51

Hawk Moths mating in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. Male moths use their branched antennae to detect the scent of a female from long distances away. This was a lucky photograph.

THAILAND’S MESOZOIC VERTEBRATES

Endemic dinosaurs that once roamed on this land

Page 52-53

Theropod footprints in Phu Faek Non-hunting Area, Kalasin province, Northeast Thailand. This is the Kingdom’s best preserved dinosaur trackway found by two school girls in 1996.

Page 54

Theropod Dinosaur Footprint in Phu Faek Non-hunting Area. This track is about 140 million years old, and is Thailand’s most intact dinosaur footprint. The creature that left this print is estimated to have weighed about 2 tons and was the ancestor to T-Rex.

During the Early Cretaceous 140 million years ago in what is now Kalasin province in northeast Thailand, a lone theropod dinosaur walked slowly along a riverbank searching for prey. Herbivorous dinosaurs also inhibited this land and were probably the main diet for the huge carnivore. This solitary hunter walked up-right. Weighing about two tons, it left massive footprints in the sandy banks of the river. Over millions of years, the sand bank eventually solidified but these footprints have miraculously remained intact. This remarkable prehistoric site is one of the Kingdom’s many

reminders when dinosaurs ruled the land.

Theropod Tooth from a Siamotyrannus isanensis found in Kuchinarai district of Kalasin province. It is in perfect condition with the serrated edge intact, and is about 130 million years old.

The Mesozoic (meaning middle life) is also known as the Age of Dinosaurs comprised of three periods: the Triassic ( 248-206 mya), the Jurassic (206-144 mya) and the Cretaceous (144-65 mya).

Dinosaurs evolved over 160 million years into a myriad of shapes and sizes. While some were the tallest and heaviest animals to ever walk the earth, others were no bigger than a chicken. Hundreds of species adapted to widely different environments. This adaptation contributed to the success and diversification of the dinosaur.

Thailand has the largest and finest representation of dinosaur fossils in Southeast Asia. The only other fossils in the region are a few small discoveries in Laos. Thai fossils show a close relationship to the Chinese and Mongolian dinosaurs.

To date, all dinosaur fossils and footprints discovered have come from Mesozoic freshwater sediments, turning into sandstone, clays and limestone.

One man has undeniably been at the forefront of the discovery of Thai dinosaurs. A walking encyclopedia on the subject, Varavudh Suteethorn is surely Thailand’s top paleontologist and geologist, of the Department of Mineral Resources. He has found more dinosaur fossils in Thailand than anyone else, and has published scores of scientific papers. Varavudh’s latest find is a stegosaur or ‘plated lizard’ of the Late Jurrasic, and more new species are bound to follow.

Eric Buffetaut and his wife Haiyan Tong of the National Center of Scientific Research in France have worked in a Thai-French project. Considered leading authorities on the identification of Thai dinosaurs, they have published many papers in collaboration with Varavudh. The meticulous work of the Thai-French paleontological team has found some 15 species in Thailand.

Page 58-59

Huai Hin Lat Formation 220 million years old in Nam Nao district in Phetchabun province, Northeast Thailand.

Page 60

Page 61

Archosaur Footprints on the Huai Hin Lat Formation in Nam Nao district of Phetchabun province. The sharp toes (Page 60) indicate this creature was a predator. Dating back to the Late Triassic period, these footprints are the Kingdom’s oldest trackway.

In time, Thailand’s dinosaurs range from the Late Triassic to the Early Cretaceous. The first fossil was discovered in 1976 in Phu Wiang National Park in Khon Kaen province. A femur from a sauropod was discovered by Sutham Yamniyom, geologist with the Department of Mineral Resources.

Then teeth from a theropod and several bones from a sauropod of the Early Cretaceous were found in Phu Wiang. (These discoveries come from the Sao Khua Formation, a very productive stratum.)

Five new species of dinosaur known nowhere else have been found in Thailand. In 1986, Siamosaurus suteethorni, a fish-eating theropod named after Varavudh, was unearthed from the Sao Khua Formation in Phu Wiang.

In 1992, a small, parrot-beaked herbivorous dinosaur, Psittacosaurus sattayaraki, only about a meter long, was excavated in Chaiyaphum province. In 1994, the largest dinosaur ever found in Thailand appeared. A sauropod of the Early Cretaceous, it was named Phuwiangosaurus sirindhornae after HRH Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn, who followed the excavation keenly. This giant plant-eater has been found at three sites on the Khorat Plateau.

Page 62

Fossilized teeth found at Wat Sakawan. These teeth belong to a Phuwiangosaurus sirindhornae from the Early Cretaceous Period, about 140 million years ago. Fossils are very important reminders and proof of dinosaur history in Thailand.

A carnivorous theropod, Siamotyrannus isanensis was found in 1996. The oldest Tyrannosaur found in the world, it is Tyrannosaurus rex’s earliest known ancestor. The next species from the Northeast is a very primitive sauropod from the Late Triassic, Isanosaurus attavipachi. It is the oldest sauropod found in the world so far. The fact that Thailand’s dinosaur discoveries have often proved to be the earliest example of lineages well known all over the world has led many scientists to believe that quite a few dinosaur species originated in Asia.

Page 63

Sauropod dinosaur fossil at Wat Sakawan, Sahat Sakhan district in Kalasin province, Northeastern Thailand. This site has seven fossilized skeletons of the sauropod Phuwiangosaurus sirindhornae.

The Kingdom’s single most significant discovery was in 1980 at Wat Sakawan, a Buddhist temple in Sahat Sakhan district, near the city of Kalasin. The temple lies at the foot of Phu Kum Khao hill and the site attracts many visitors all year round. The first fossils were found and kept at the temple. Subsequent excavations by Thai-French paleontologists in the Sao Khua Formation then discovered seven fossilized skeletons of the sauropod Phuwiangosaurus sirindhornae. Several fragments of theropod teeth were found at the same site suggests scavenging on the sauropod carcasses. Theropod teeth were also discovered together with sauropod fossil bones at Phu Wiang.

In 1996, two schoolgirls spotted two sets of dinosaur footprints in the Phra Wihan Formation at Phu Faek Non-hunting Area in Kalasin province. The two-ton, three-toed theropod dinosaur portrayed at the beginning of this chapter made the clearest and best preserved footprints in Thailand, a total of 21. A smaller set criss-cross the larger set. The prints unfortunately lie in a seasonal stream and are covered with running water during the rainy season.

In 2003, a set of tracks were found by the Nam Nao Conservation Group in Nam Nao district, Phetchabun province. Villagers told of footprints which they believed had been made by the spirits of the forest. Superstition plays a big part in their lives.

Page 66-67

Phra Wihan Formation of the Early Cretaceous Period in Phu Faek Non-hunting Area, Kalasin province, Northeast Thailand.

The conservation group contacted Varavudh Suteethorn, who investigated and determined that the tracks had been made on a huge mud flat by an archosaur or ‘ruling reptile’ sometime during the Late Triassic, 220 mya. (This formation is known as Huai Hin Lat.) Over millions of years, the 200 by 250 meter slab somehow remained intact as geological forces thrust it up to a 40 degree angle. There are three separate trackways, and they are the Kingdom’s oldest fossil footprints. Because this important site is situated just outside Nam Nao National Park, it is not in protected land. Like all fossil sites, it needs absolute protection if it is to survive.

The downside of Thailand’s wonderful discoveries is that fossils are in big demand by both local and international collectors, stimulating village people to pillage fossil sites. Some fossils even end up cold at tourist venues as curios. Knowledge of millions of years of evolution is being lost to wanton ravaging of these sites. It is essential that the looting be controlled.

Thailand has gained the role of a major dinosaur site, in fact one of the richest in the world. Thai fossils are revealing very important information about Mesozoic dinosaurs in Asia. The joint Thai-French search for fossils continues, and surely new revelations will emerge from the rock stratum to delight paleontologists worldwide. Thailand’s dinosaur fossils are priceless and are truly a tribute to the Kingdom’s natural heritage.

SUBMARINE OF THE JUNGLE

The last wild Siamese Crocodiles in Thailand

Page 68-69

A Siamese Crocodile in Klong Takrow in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary, Eastern Thailand with a forest fly resting on its bony ridge.

Two hundred and thirty million years ago, the first crocodiles began to evolve during the Mid-Triassic period of the Mesozoic era. Having branched off from archosaurs or ‘ruling reptiles’ when primitive dinosaur also roamed the planet, crocodilians have changed little in body structure since then. Apart from birds, crocodiles are the only living archosaurs.

In 1909, J.B. Hatcher discovered a few fossilized bits and pieces of a giant crocodile in Montana from the Late Cretaceous period 80 mya of North America. Deinosuchus was also found in Texas by Barnum Brown of the American Museum of Natural History in New York in the 1940s. The skull of this huge crocodilian is two meters long and body length estimated at more than 10 meters. Sarcosuchus, a 12 meter crocodile, was found in Central Africa from the Early Cretaceous 110 mya by France de Broin and Phillip Taquet in 1966. A huge crocodilian was also found in Brazil by a British geologist, and described by Eric Buffetaut and P. Taquet in 1977 as the same species found in Africa. These ‘super-crocs’ pulled dinosaurs into the water and devoured them.

Page 70-71

Siamese Crocodile in Kaeng Krachan National Park, Southwest Thailand. This individual was photographed in 2003 along the Phetchaburi River deep in the interior. The species is considered the rarest wild crocodilian in the world.

In 1979 in the northeast province of Nong Bua Lam Phu, Nares Sattayarak, a geologist for the Department of Mineral Resources, discovered the lower jaw of a huge crocodile in a road-cut excavated from the Phu Kradung Formation of the Late Jurrasic 150 mya. Sunosuchus thailandicus was described as a new species by Eric Buffetaut and Rucha Ingavat (also from the Department of Mineral Resources). Estimated to have been at least eight meters in length and with a lower jaw over a meter long, it was Thailand’s ‘super-croc’.

Crocodilians for most of their 230-million-year history have been large, long-bodied, aquatic carnivores. Armor-plating (in the form of bony scutes set in their hides), extended tails, short strong limbs, and powerful sharp-toothed jaws made them into formidable predators.

Crocodiles come onto land to defecate and, being cold-blooded, bask in the sun so as to regulate their body temperature. Female crocs come ashore to lay from 20 to 40 eggs in mound nests on land near the water’s edge. These streamlined predators glide through water with ease, surfacing and submerging at will. Man is the mature crocodile’s only enemy, and the wild Siamese crocodile are the world’s most endangered crocodilian species.

Siamese crocodiles grow broad and heavy. Mature individuals have distinct bony ridges behind the eye socket. Historical records report specimens of up to four meters in length but three meters is presently average for an adult. They feed primarily on fish but also take frogs, small mammals and birds. Undulating their powerful tails while tucking in their legs, crocs can glide through water without making a ripple. Stealthily stalking prey along the water’s edge, in an instant they can snatch their victim in powerful jaws and pull it below to drown it. Some species lay in wait on the bottom of a river or pond in order to grab fish. (Crocs can stay underwater for long periods of time.) Adults can survive a year without a meal and thus are nature’s most efficient predator in terms of consumption in proportion to body size.

Page 72-73

Siamese Crocodile camera-trapped along Klong Takrow in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary. This individual is the same animal shown on page 68-69. Siamese crocodile hunt mostly fish but also take small birds and mammals.

Thailand once had three species of crocodile found in a host of enviroments: the sea, estuaries, rivers and marshes throughout most of the country. The most common species was the Siamese crocodile Crocodylus siamensis, a freshwater species. Another freshwater crocodile was the Tomistoma schlegelii, also known as the ‘false gharial’. This thin-snouted crocodile was only found in rivers of the southern peninsula. The estuarine saltwater crocodile Crocodylus porosus, is the largest croc in the world. Also known as the ‘Indo-Pacific’ crocodile, it was very common in river estuaries and islands in the Gulf of Thailand and the Andaman Sea. These huge saltwater crocodiles could even be seen swimming in open ocean.

The tomistoma and saltwater crocs are probably extinct in the wild in southern Thailand, but, along with the Siamese, they are farmed. The freshwater tomistoma and Siamese can live in the brackish water found in most farms. A fast growing crocodile has been hybridized by cross-breeding the Siamese and saltwater crocodiles. This human creation is the crocodile most often farmed for its meat and hide.

Siamese crocodile were once very common in Southeast Asia including Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Laos and possibly Burma. Populations throughout the region have declined and exact numbers of wild crocs are not known in any of the range countries.

Page 74

Klong Takrow in Khao Ang Rue Nai. This river dries up in the winter leaving small but deep ponds. Many species of fish survive in this habitat and are the main diet for the Siamese Crocodile found here.

At the end of World War II, crocodile farming came into vogue in the Kingdom, and wild crocs were captured for breeding stock. Thousands upon thousands were caught in the booming trade. Habitat loss and crocodile farming started the countdown to extinction for these ancient creatures. There were no laws to protect them and the crocodiles was eradicated from every river and swamp in the country. Only the Siamese crocodile survives in a few places in the wild.

Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary in the province of Chachoengsao, is about three hours drive from Bangkok. It was established in 1977 and the protected area, consisting mainly of semi-evergreen forest and many streams, is eastern Thailand’s largest remaining tract of lowland rainforest, with a rainfall of some 3,000-4,000 millimeters a year.

This wilderness was almost completely surrounded by agricultural land, and squeezed down to the last 1,030 square kilometers before being gazetted by royal decree. Fortunately, enough forest was saved that elephant, gaur, banteng and many other animals have been able to survive so far, including birds such as the black-and-red broadbill and the Siamese fireback pheasant. Khao Ang Rue Nai is home to one of the last wild Siamese crocodiles in eastern Thailand.

The opportunity to photograph one of Thailand’s rarest animals had been a dream of mine for some time. In January 2001, I erected a photographic blind on the banks of Klong Takrow close to where a croc had been seen basking.

Page 75 – Photo by: Kitti Kreetiyutanont

Siamese Crocodilein Khao Ang Rue Nai. This mature crocodile was photographed in 1993 by Kitti Kreetiyutanont who did a survey of wild crocodiles in the Kingdom for the Royal Forest Department.

The murky waters of the forest pool lay still and quiet in the mid-morning heat. Now and then a fish catching an insect or a falling leaf would disrupt the mirror image of the pond. A pair of wreathed hornbills croaked nearby while high in the trees, pileated gibbon sang a booming crescendo. It was nature at its best.

Page 76-77 – Photo by: Kitti Kreetiyutanont

Siamese Crocodile in Khao Ang Rue Nai photographed back in 1993.

Dripping with sweat, I sat hoping to see a crocodile. A slight movement in the water at the far end of the pool caught my eye. A strange but familiar shape surfaced and then submerged, moving closer to its basking spot. Slowly, its eyes and snout rose to the surface. A large forest fly landed on the bony ridge behind its eye to drink the salty secretions from the croc’s eye (Page 68-69). As the reptile checked the surrounding area for danger, I snapped a long series of photographs of Thailand’s most endangered animal. Suddenly, as if sensing it was not alone, the croc submerged and disappeared into the depths of the pool. My dream had come true and 230 million years of evolution had passed through my lens.

For capturing images of such elusive creatures like crocodiles, infrared camera-traps is a very productive alternative to endless days of sitting in a hot photo-blind. Crocodiles are creatures of habit, so I set a camera-trap at its favorite basking spot. The croc was caught on film many times during a two-week session, the best shot being on page 73. Since Siamese crocs can live for 60-70 years, it is hoped this individual will be in Khao Ang Rue Nai for a long time to come.

Kaeng Krachan National Park, mostly semi-evergreen forest, is the Kingdom’s largest national park with an area of some 2,915 square kilometers. Probably Thailand’s most intact remaining ecosystem, much was saved from logging by the ban in 1989. The main water course is the Phetchaburi River, which flows down to the Kaeng Krachan reservoir from the Tenasserim Mountain Range staddling the border with Burma. Kaeng Krachan is just three hours drive southwest of Bangkok.

Many species still thrive in the park: elephant, gaur, tiger, leopard, and many more including the Siamese crocodile. In early 2001, park rangers found crocodile tracks along the river and a Siamese crocodile was camera-trapped on a sandbar. A few months later, I found another set of tracks further up-river from the first set. No crocs were sighted at this time, but a population may exist in the interior nonetheless.

In March 2003, while tending camera-traps along the Phetchaburi River, I found crocodile feces and tracks at the 2001 site where I built a photographic blind across the river. After a two day wait, a mature croc emerged at the deep end of the pool in mid-morning. Fortunately, it was within range of my Minolta 600mm lens and 2X tele-converter. Several rolls of film later, the rare croc submerged and disappeared. These photographs are the first ever through the lens of a Siamese crocodile in Kaeng Krachan.

Both brief encounters will remain etched in my memory for as long as I live. The solitary crocodiles have instilled an urge in me to help these rare creatures – but how?

As of 2004, Khao Ang Rue Nai and Kaeng Krachan are the only known sites where the Siamese crocodile is found – and only one animal is confirmed at each site. In 2003, a female croc with eggs was killed by poachers in Yot Dom National Park not far from Cambodia. Its skull and skin are now on display at the park.

Page 78

Crocodile Tracks along the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan National Park. Crocodiles are creatures of habit and come to the same spot to bask and deficate unless disturbed. This river is also home to the otter, fish-eagle and water monitor.

Some old reports suggest that Siamese crocodile may still exist in the northeast in several other protected areas: Pang Sida National Park (Sa Kaeo province) and Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary (Chaiyaphum province). Kitti Kreetiyutanont of the Royal Forest Department, wrote a paper on Siamese crocodile sightings in 1993 and, indeed, photographed the croc at Khao Ang Rue Nai.

The National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department and other organizations should support surveys to see if other crocodiles still exist in Thailand. With only a couple of animals confirmed, action must be taken to ensure their survival. Restocking a few carefully selected sites with yearling Siamese crocodiles seems to be the only solution. But that raises questions about the farmed crocodiles available for release. Have farmed Siamese crocodiles been subject to excessive inbreeding? Even more critical, have they been crossbred with other species? Only good DNA analysis can unravel this intricate problem of the species integrity in captivity.

Page 79

Crocodile Pond along the Phetchaburi River. This waterway could possibly be a reintroduction site in the future for the extremely endangered reptile, but extensive surveys are required to determine if a viable population exis. Only one individual has been photographed and camera trapped here.

Serious efforts are required to save Thailand’s remaining wild crocodiles from total extinction. No matter how many crocodiles are kept in farms, only an intact wild population can save these ancient creatures.

Public access to the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan and to Klong Takrow in Khao Ang Rue Nai should be limited and strictly regulated. These crocodiles need absolute protection if the species is to continue to survive the dinosaurs. Thailand should serve as a role model for wildlife conservation in Southeast Asia, and the people need to join hands to protect their Kingdom’s natural heritage for future generations.

TO BE CONTINUED IN ‘PART TWO’

The River Runs Wild…!

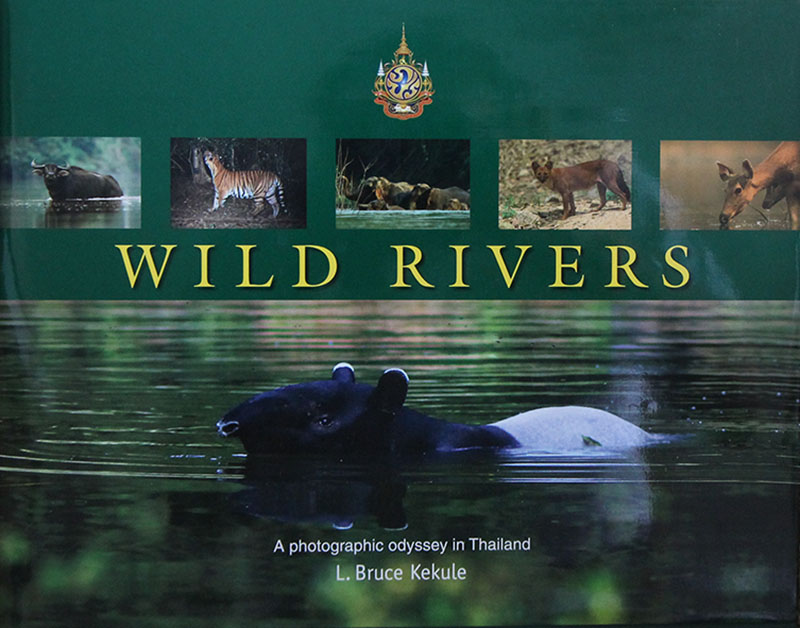

THIS POST IS THE SECOND IN A SERIES OF WILDLIFE STORIES THAT WERE PUBLISHED IN THE BANGKOK POST. IT IS ABOUT THE FIRST EDITION OF MY THIRD BOOK TITLED ‘WILD RIVERS’

Photographic book focuses through the lens of Thai national heritage on five rivers

By: PANYAPORN PRUKSAKIT

A culmination of 12 years work and including a selection of more than 300 photographs, Bruce Kekule’s Wild Rivers is truly a photographic odyssey. From the front cover, graced by the Asian tapir, an animal so rare it is considered a living fossil, one feels like this will be a truly special read. Kekule’s 20 years’ experience as a wildlife photographer, trekking and again through Thailand’s jungles, is invaluable to his epic undertaking, this his third book.

An old banteng bull and cow at a waterhole in the Western Forest Complex of Thailand

Kekule calls this a continuation of his dedication to the “Thai Natural Heritage” with Wild Rivers dedicated to His Majesty the King on his 80th birthday anniversary. On why he chose these particular rivers – the focus of this book is on fiver rivers: The Phetchaburi. Huai Kha Khaeng, Mae Klong, Khwae Noi and the Mae Ping – Kekule remarks the main reason was that they still have wildlife left, he says, as humans have been relentless in their expansion and development plans on other waterways.

Having lived in Thailand for over 40 years, he says that these rivers and the surrounding jungles are some of his favorite places in the country. A rather spiritual man, he recalls how the inspiration for his series of wildlife photography books came to him in a dream. Kekule’s passion for his career of choice is evident – one of his favorite quotes is by the Chinese philosopher Confucius, that one should choose a job you love and you will never have to work a day in your life.

An Oriental Dwarf Kingfisher in Kaeng Krachan National Park, Southwest Thailand

From the opening pages of Wild Rivers, it is clear that Kekule not only seeks the natural beauty of Thailand’s rivers with the reader, but also to inform and educate about these “natural treasures”, as he calls them. As Kekule states in his forward, “without water, there would be no life.” The book begins with a history of Thailand’s formation, and the importance of Thailand’s rivers – what Kekule calls “the lifeblood of the nation”…(as) plants, animals and humans carry out (their) daily lives dependent on water.”

Kekule’s extensive experiences is evident in the clarity, sharpness and vivid colors which define all of his photographs. But what makes Kekule’s shots truly spectacular is that the animals he captures on film are truly in their natural habitat, almost unaware of his presence.

Equally as rivetingas the photographs, which fill the book is the narration from Kekule himself, about his adventures while writing the book. Entitled “notes from the field”, he tells of his encounters with rare creatures such as the king cobra. These stories are both endearing and amazing at the same time – he recalls how he “felt extremely happy at helping to save this beautiful bird of prey from dying,” upon finding an “owl going into shock from hypothermia” and using the campfire to warm-up this creature from a certain death.

Wild pig along the river in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary

Kekule seems to have had more than his fair share of luck – indeed he concedes that he has been luckier than most other wildlife photographers, in coming upon rare animals such as the Asian tapir in the daytime. They are primarily nocturnal and hardly seen in the day, let alone photographed with good light. But he believes strongly in the “spirits of the forest”, whom he believes guide and help him. He writes how he pays his respects to the spirits – always before eating.”

However, Kekule’s career as a wildlife photographer has not been without its occupational hazards. He recalls in his book how he “became ill with the deadly Plasmodium falciparum (celebral malaria) that almost killed [him].” Kekule states that only a “medical procedure practiced here in Thailand for patients with severe malaria called a blood exchange transfusion” saved him. While he comments that he was lucky to survive”, even this experience has not kept him from capturing the wildlife of Thailand. However, he now takes some wise precautions that he did not previously adhere to, such as not photographing in the monsoon season.

Wild Rivers – 1st Edition dedicated to His Majesty the King on his 80th birthday anniversary

Kekule states how he will continue with his career for as long as he “can hold a camera and walk”, such is his determination. The most gripping and urgent message of Wild Rivers is found in the penultimate section of the book, entitled “Wildlife in Peril: Dangers threatening the natural world”. Kekule writes about how Thailand’s ecosystems are being progressively destroyed by encroachment, poachers, the black market and the traditional Asian medicine trade. He also writes how education and aid for local village Thais and hill tribe people is needed as middlemen “flash money at the people who are mostly poor and easily persuaded to break the law in order to feed this voracious [black market] trade.” Kekule outlines a step-by-step plan for the government, for “taking care of the natural resources” of Thailand, which included suggestions about budgets and addressing grassroots problems.

Kekule’s love of Thailand as a nation, and the setting for his wildlife photography adventures, is evident in every page of Wild Rivers. He hopes that his books will serve as part of education, which must be implemented in Thai schools to change the mentality towards wildlife and nature, and promote their conservation rather than their destruction. The stunning beauty of Kekule’s book and its important message can certainly not go unnoticed, if only because of the great artistry it showcases. But perhaps the reader can also take away Kekule’s message that “all humans have a right to exist, but unfortunately, not at the expense of the natural world.”

Published in the Bangkok Post’s Outlook Section on November 10, 2008. The photos shown were actually used in the newspaper article when it was published.

LAST OF WILDLIFE TRIOLOGY

THIS POST IS THE THIRD IN A SERIES OF WILDLIFE STORIES THAT WERE PUBLISHED IN THE BANGKOK POST. WRITTEN BY USNISA SUKHSVASTI

LAST OF WILDLIFE TRIOLOGY

Male Indochinese tiger at a water hole in the Western Forest Complex

Wild Rivers: A Photographic Odyssey in Thailand is the third in a series of wildlife books — the first two were Wildlife in the Kingdom of Thailand and Thailand’s Natural Heritage – by L. Bruce Kekule, respected wildlife photographer and long time resident of Thailand. His books follow a pattern; First is an English-language edition, followed by a Thai language one.

Wild Rivers (1st Edition) was published in 2008, as dedication to His Majesty the King on the auspicious occasion of his 80th birthday, and the Thai edition (2011) recently out at the same time as the second-edition of the English version, dedicated to His Majesty the King on his 84th birthday, with the aim of sharing the beauty of the country’s natural heritage and its wildlife with the Thai people.

Wild Water Buffalo in the Huai Kha Khaeng River

The book covers six of Thailand’s major waterways: The Phetchaburi River, Khlong Saeng River (a new addition to the first edition), Huai Kha Khaeng, Mae Klong River, Khwae Noi River and the Mae Ping River.

The introduction describes the geographical locations of each river, emphasizing as always the importance of preserving these watersheds and the habitat for resident wildlife.

Black-and-red broadbill in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Each river is illustrated with photographs that he has collected from his forays into the wild over the past 12 years, allowing readers to admire the country’s wild animals in their natural habitat.

The book also includes a chapter on Thailand’s nature photographers where 1o Thai photographers and one foreign photographer have shared some of their most cherished images.

In the ‘Wildlife Photography’ chapter, Kekule shares tips and personal experiences gained from his decades in the field, his choice of equipment, the need for patience, the art of stealth, camera techniques, and even computer skills. He also mentions the hazards and dangers of being in the field, not only threats from large animals but also from the tiniest of creatures like ticks, ants and mosquitoes…!

He ends with a plea for nature conservation in ‘Wildlife in Peril’ to create awareness among readers to the diminishing numbers of animals in the wild due to human ignorance or greed.

Wild Rivers – 2nd Edition dedicated to His Majesty the King on his 84th (7th Cycle) birthday

Wild Rivers – Thai Version (1st Edition) also dedicated to His Majesty the King on his 84th (7th Cycle) birthday

Readers can be sure of a visually pleasing read. Wild Rivers received a gold medal for the “Best in Sheet-fed Offset” and another gold award for “Best 4-color Printing” at the Thai Printing Association’s 4th Thai Print Awards in 2008.

The Thai version titled ‘Sai Natee Haeng Pong Prai was translated by Capt. Araya Amrapala, PhD.

Note: The photos shown here were actually used in the newspaper article when it was published.

The Asian Leopard – Thailand’s 2nd largest wild cat…!

This film is a culmination of videos and still photographs of leopards captured by video and DSLR camera traps in the ‘Western Forest Complex’ of Thailand. The first black cat video was taken just a few months ago. Enjoy..!