The Asian Tapir – Living fossil and bizarre mammal

Odd-toed ungulate and strictly vegetarian

The Asian tapir still thrive in Thailand’s dense evergreen forests in the West and South

It was an amazing day in March 2005 near the headwaters of the Phetchaburi River deep in Kaeng Krachan National Park situated along the border with Burma in southwest Thailand. One morning, a buffy fish-owl found stuck in a fishnet was going into shock from hypothermia. I luckily saved this creature from certain death.

Asian tapir posing in the Phetchaburi River

The campfire was going well and I used it to warm up the bird of prey. When it could stand by itself, I placed it on a tree branch and then played wildlife photographer for a short while. I then left the confused animal in peace and it eventually flew across the river and disappeared into the forest. I felt good saving the owl. Under other circumstances, it might not have fared too well.

Buffy fish-owl saved from certain death

Later in the day as we were up-river and just about ready to turn back, a huge king cobra showed-up hunting for prey along the riverbank. I was able to catch a few photographs of the largest venomous snake in the world before it U-turned and disappeared into the forest.

King cobra hunting by the Phetchaburi River

That definitely got the blood flowing as I checked out my shots on my brand new Minolta D7 D-SLR digital camera, the first with anti-shake technology in the camera body. I shot off-hand and was getting some acceptable digital captures. When the smoke cleared, I had only two shots left on the card and decided not to delete any poor exposures as I felt nothing would show after the big snake.

Asian tapir swimming in the Phetchaburi River

It was about 4pm and the light was nice and warm as we headed back to camp more than an hour away. Just then, an Asian tapir bounced out of the forest and dived into the river. It submerged for a short time probably trying to evade a swarm of biting forest flies before surfacing and swimming towards us. I took a shot waiting for the ungulate to get closer. It stopped in the water about twenty meters away.

The tapir has very poor vision and it took a few seconds before the unusual creature saw five humans standing out in the open. Just as I snapped my last shot shown in the lead photo, it swam away and jumped back into the forest it had come from. Seeing one of nature’s remarkable animals, even though briefly, is the ultimate thrill for me.

I know I missed quite a few shots because of old age forgetfulness (not having spare memory cards), but then again, the two shots I captured were more than enough. I was thrilled to capture the world’s largest tapir in broad daylight offhand. If I used a tripod that day, I might have missed it. These creatures are mainly nocturnal and rarely seen during the day. This event was truly the beginning of a new dream and this tapir made the front cover of my third book Wild Rivers. It certainly was special for me, and is etched in memory.

In Thailand, photographing three separate species in one day is surely a rare occurrence as most animals are now tough to see and photograph, especially the tapir. It must have been something about saving the owl earlier in the day and the ‘spirits of the forest’ made up these magical sightings. I will never know. It had been a dream of mine to photograph a tapir in the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan National Park after seeing a painting in a book produced by the Tourist Authority of Thailand (TAT) about the park.

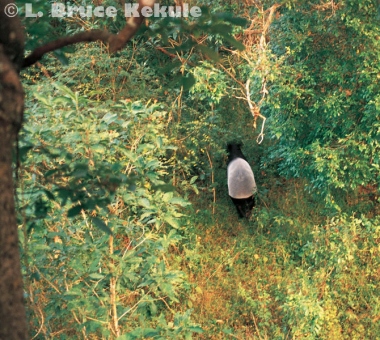

My first tapir from a tree-blind in Huai Kha Khaeng

Years ago when I made regular trips to Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in western Thailand, one visit stands out as a lucky tapir sighting. There is a hot spring deep in the interior that attracts all sorts of large mammals including the tiger, leopard, elephant, gaur, banteng, and the tapir among others. This mineral deposit is part of a complex natural seep several hundred meters long. I was sitting at the bottom-end in a tree blind about eight meters up and waited throughout the day until about 5pm. A few sambar stags came for a drink followed by a doe. A barking deer nervously stepped in but somehow was spooked by something on my right and departed.

My first tapir moving in the forest under the tree-blind

A few minutes later, a black and white creature plowed through the brush and popped out into the clearing. I quickly snapped off a bunch of frames with my Nikon camera and 600mm lens as the tapir took a long drink filling the frame with the large mammal. The tapir then moved under the tree I was in and I managed a couple of shots with a smaller lens as the tapir disappeared into the forest behind me. In those days I was shooting film and was not sure my photos were good until I processed the film back in Bangkok. Shooting black and white mammals is fraught with exposure problems but most of the shots were OK. It was my first lucky sighting of an animal known for its secrecy and nocturnal habits.

Tapir and gaur photographed at a hot-spring in Huai Kha Khaeng

Another memorable tapir sighting was not by me but my close friends, Samak Khodkaew, Amonsak Sirwichai, Sarawut Sawkhamkhet and Ajarn Prapakorn Tarachai. These gentlemen are nature photographers and have helped me in the past with my book projects. I set the four of them up in a permanent photographic blind about noontime at the top-end of the hot spring mentioned above. I then waited for them back at the truck.

Just as darkness arrived, a bull gaur and a tapir arrived almost together. I have never seen a bunch of excited photographers like this group when they finally came out. Two species in one photo is also quite an achievement. I was happy and glad the ‘spirits of the forest’ had smiled on them.

Asian tapir camera trapped in Kaeng Krachan

When I began a photographic and camera-trap program in 2005 along the Phechaburi River in Kaeng Krachan, it was not long before I caught a mature tapir at a mineral deposit late one night. They are thriving there as are other large mammals like tiger, leopard, sun bear, wild dogs, elephant, gaur and sambar.

Asian tapir mother and calf camera trapped in Khlong Saeng

In early 2009, I started a new program in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Surat Thani province down South. I now have quite a few camera trapped tapir photos where the species is proliferating. The flooded forest of Cheiw Larn reservoir habitat is now unnatural for them but they have adapted to the changed landscape. These amazing herbivores are surviving quite well in the mountains of Khlong Saeng-Khao Sok Forest Complex.

Tapir calf camera trapped in Khlong Saeng

However, tapir numbers have decreased in recent years, and today, like all of the species, is in danger of extinction. Because of their size, tapirs have few natural predators, and even reports of killings by tigers are scarce.

Young ear-bitten tapir camera trapped in Khlong Saeng

The main threat to the Asian tapir is human activity, including hunting for meat, deforestation for agricultural purposes, flooding caused by the damming of rivers for hydroelectric projects, and illegal trade. Protected status in Thailand, which seeks to curb deliberate killing of tapirs but does not address the issue of habitat loss, has had limited effect in reviving or maintaining the population.

In closing, this remarkable wild animal is just another cog in the wheel of Mother Nature’s wonderful array of species adapted to living in the evergreen forests of western and southern Thailand. Their survival depends on one thing: protection and enforcement of the protected areas where they live. Over the long run, it is up to the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, and the Department of National Parks to insure that the tapir and all the other beautiful creatures get the best possible safeguards for the future. It is hoped the powers to be will take action to prevent further destruction of the Kingdom’s natural resources.

Tapir up-close

Tapir are considered living fossils as the genus has been traced back as far as Early Oligocene times. These remarkable mammals have been on the planet for about 40 million years. The first tapirs are named Miotapirus judging from fossil evidence found in North America. Tapiridae, a sub-family belong to the Order Perissodactyls, or odd-toed ungulates that goes back to the Late Paleocene 55 million years ago including rhinoceros-like creatures evolving in North America and eastern Asia from small animals similar to the first horses.

The Asian tapir Tapirus indicus, also called the Malayan tapir, is the only one native to Southeast Asia. It has an unmistakable black and white two-tone pattern distinguishing it from the other three tapir species of Central and South America. The Asian species is the largest, and is the only ‘Old World’ tapir with the females slightly larger than the males. They live in the rainforests of Thailand, Myanmar, Malaysia and Sumatra.

The general appearance and characteristics of the Asian tapir is easily identified by its markings, most notably the white “saddle” which extends from its shoulders to its rump. The rest of its hair is black, except for the tips of its ears, which, as with other tapirs, are rimmed with white. This pattern is for camouflage as the disrupted coloration makes it more difficult to recognize it as a tapir at night, or in the dark jungle during the daytime that they prefer. They are mainly nocturnal but do show sometimes in the late afternoon at the river or mineral deposit. Other animals like tiger may mistake it for a large rock rather than a form of prey when it is lying down to sleep.

The Asian tapir grow to between 1.8 to 2.4 m in length, stand 90 to 107 cm tall, and typically weigh 250 to 320 kg, although they can weigh up to 500 kg. The females are usually larger than the males. Like the other types of tapir, they have small stubby tails and long, flexible proboscises. They have four toes on each front foot and three toes on the back feet.

The tapir has very poor eyesight, and making them rely greatly on their excellent sense of smell and hearing to go about their everyday lives. The tapir has small, beady eyes with brown irises on either side of their face. Their eyes are often covered in a blue haze, which is corneal cloudiness thought to be caused by repetitive exposure to light. Corneal cloudiness is when the cornea starts to lose its transparency.

The gestation period of the Asian Tapir is approximately 390-395 days, after which a single offspring, weighing around 6.8 kg, is born. Young tapirs of all species have brown hair with white stripes and spots, a pattern that enables them to hide effectively in the dappled light of the forest. This baby coat fades into adult coloration between four and seven months after birth. Weaning occurs between six and eight months of age, at which time the babies are nearly full-grown, and the animals reach sexual maturity around age three. Breeding typically occurs in April to June, and females generally produce one calf every two years. Asian Tapirs can live up to 30 years, both in the wild and in captivity.

Tapir are primarily solitary creatures, marking out large tracts of land as their territory, though these areas usually overlap with those of other individuals. Tapir mark out their territories by spraying urine on plants, and they often follow distinct paths that they have bulldozed through the undergrowth.

Exclusively vegetarian, the animal forages for the tender shoots and leaves of more than one hundred species of plants (around 30 are particularly preferred), moving slowly through the forest and pausing often to eat and note the scents left behind by other tapirs in the area. They tend to eat soon after sunset or before sunrise, and they will often nap in the middle of the night.

However, when threatened or frightened, the tapir can run quickly despite its considerable bulk. They can also defend themselves with their strong jaws and sharp teeth, and have thick hides protecting them from predator attack. They communicate with high-pitched squeaks and whistles. They usually prefer to live near water and often bathe and swim, and they are also able to climb steep slopes.