Archive for the ‘Journal Entries’ Category

Escape to Nature – Photographing rare animals

Visiting the forest during Songkran: Thailand’s New Year and water festival

Huai Kha Khaeng reveals some wild endangered Asian creatures

Indochinese tiger camera-trapped in Huai Kha Khaeng

When I was 19 years old, I arrived in Bangkok at the end of March spending a week or so in the ‘City of Angels’ enjoying the sights and sounds. This was in 1964 just as the Vietnam War was getting into high gear. Pollution was mild and the klongs were not that bad.

I remember riding around in Datsun Bluebird taxis with no air-con and watching the road flash-by between my feet. The gaping hole made me nervous but the capital was an amazing experience all stored in the old memory bank.

Banteng bull and cow at a waterhole in Huai Kha Khaeng

After the hustle and bustle of the city, Dad and I caught the train headed north to Chiang Mai. The next morning at dawn, we passed through Phrae province surrounded by misty mountains. I opened the window and the cool breeze was refreshing. I instantly fell in love with the countryside and decided that Thailand was for me.

We arrived in the northern capital just in time to celebrate Songkran water festival for the very first time. As a teenager, it was a blast. But it was still tough getting around on my motorcycle as the main object of some people especially at intersections was to kill the bike, and then completely drench the rider (me) with water and powder.

Bull gaur arrived at the same waterhole a few minutes after the banteng

Yes, downtown Chiang Mai and the surrounding countryside was a madhouse even back in ‘64’. Songkran lasted for more than seven days in the north starting a few days before April 13th and finishing up a couple of days after the 15th.

As Thailand’s northern forests and mountains provided plenty of water for the festival, there was a seemingly unlimited supply. The watersheds were still very healthy at that time. In late March – early April, the temperature was cool in the evening and warm to hot during the day.

Crested Serpent-eagle flying out of the same waterhole

Eventually I met-up with some fellow Americans and the three of them are life-long friends to this day. John C. Wilhite lll was attending classes at the newly built Chiang Mai University, and his father was a Major in the U.S. Air Force for JUSMAG (Joint US Military Advisory Group) advising Royal Thai Air Force personnel on tactics and operation of AT-28 training aircraft. Johnny and I still continue to communicate after all these years.

Wayne (Beak) Sivaslian and Ed (Mac) McDonnell with the U.S. Army were stationed in Chiang Mai. Their mission was sensitive and classified but we were close friends and still are to this day. We recently held a 40-year reunion back in the States.

Asiatic jackals at a ranger station in the interior

When Songkran rolled around, we got out the old U.S. Army deuce and a half (2 1/2 ton truck) and took off the tarp and filling the back with three or four 200-liter drums with water and ice. We then headed downtown to do battle. As we were higher up than most, we had an advantage and usually won the water fights. At the end of the day, our lips, hands and feet would turn blue and we would be shivering but boy was it fun. Finally, the police outlawed trucks with large drums of water but that did not last long.

Asiatic jackal on the run

One year, I took my family including the wife and daughter plus all the in-laws out on the town in the back of my old Series One Land Rover with no cover, doors or windows. I was the driver and had to keep my wits about me. As we were nearing Suan Dok Hospital, a drunken hooligan dipped a bucket full of dirty klong water to the brim. He then threw the entire load straight into my ribs and face with extreme force from a distance of less than a meter, and that really hurt. All he did was laugh. However, with the family in tow, I kept my cool and carried on.

Asiatic jackal on the run

That was the last time I drove an open vehicle out on the streets of Chiang Mai during the festival. I once saw a bunch of people by the Ping River with a platform and fire-fighting nozzle in a tree, and a pump down by the water’s edge (obviously from the fire department nearby). After a day, the police came around and shut them down as they had damaged several cars with the high-pressure spray.

I went running through town with the Hash House Harriers a few times but again, it was even worse with water in my ears, eyes, nose, and usually contracting a serious cold afterward. I finally decided to retire permanently from the madness.

Abstract- Asiatic jackal on the run

Some may wonder why I am talking about Songkran in this post but it is the main reason I now ‘run away to nature’ every year to enjoy peace and quiet, the birds and bees plus the refreshing coolness of the deciduous and evergreen forests I frequent. No traffic jams or crazy water-throwing people here.

This year I was granted permission to enter Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary by the Wildlife Conservation Division in the Department of National Parks (DNP) to photograph wildlife. It was a great opportunity and I made the best of it.

Jackal pair near the ranger station

Leaving Bangkok on the 11th of April, I arrived at the headquarters and met-up with the new chief Uthai Chansuk who was there to meet me. After consultations with him, I made my way into the interior with three other friends to a ranger station and settled in for a day.

A Thai friend and fellow wildlife photographer Sarawut Sawkhamkhet, has been with me on many occasions and knows this place well. He opted to sit in a permanent blind situated at a mineral lick close to the station.

Jackals chasing each other

My other two friends are Paul Thompson and Ian Edwardes, both Englishmen, and they set-up temporary blinds not far away. These two keen photographers got barking deer and a banteng bull on the very first day.

In the meantime, the rangers took me down to a platform overlooking a water hole and mineral deposit several hours walk away. We arrived at the blind about 10am and they went back to the station. I settled in for an overnight stay. I had plenty of water and food, and the weather was cool. Fortunately, my hammock fits perfectly between two trees that are part of the structure. This was April the 14th as the water festival was in full tilt.

Crested serpent-eagle taking off

The afternoon dragged on and about 2pm, a crested serpent eagle came for a drink. The raptor stayed for short while taking in copious amounts of water and then lifted off while I got a series of shots. About 5pm, as if the ‘Spirits of the Forest’ had granted my wish, a herd of banteng showed up coming straight down to the water hole for a refreshing drink. A huge bull with an enormous set of horns pushed his way through. I immediately began shooting my cameras. All of a sudden, they spooked and retreated up the hill. I thought they had scented me but this was not so.

Banteng herd at the waterhole in late afternoon

Just then, a huge mature bull gaur came down to the waterhole from the same direction as the banteng had come. Two species of large wild bovid in less than five minutes is simply amazing. This bull is very old with many rings at the base of his horns with both tips almost completely worn down. Definitely near the end of his life.

Gaur bull taking a drink at the waterhole

Dr Sompoad Srikosamatara at Mahidol University and Dr Naris Bhumpakphan at Kasetsart University estimated this solitary bull to be somewhere between 14-16 years old judging from the amount of rings. This old boy stayed at the waterhole for more than a half hour taking in his fill. He then snorted and bolted up the hill looking extremely powerful and quick on his hooves.

Lone gaur bulls will sometimes shadow a banteng or gaur herd for protection against tiger attack and poachers. They also sometimes team-up with other bulls. Simply put, more eyes, ears and noses act as security from predation.

Wild pig at the waterhole just before darkness

However, it was not my scent that had spooked the ungulates as a mature wild boar with large tusks then came for a drink just before darkness. Eventually, night set in. I had my little gas stove and boiled up some water for noodles and coffee. After eating, lightning and thunder began in the west but eventually subsided. The weather was nice and crisp, and I slept like a log.

Mineral hot spring deep in the interior of Huai Kha Khaeng

The next morning, I was up at daybreak. After a quick cup of coffee, the banteng herd from the previous day came to the waterhole again. This time they stayed for some time taking in refreshment. Funny enough, the bull had a leafy branch stuck between its left ear and horn. I of course kept shooting until they had gone. These cattle are rare in Thailand and tough to see in the wild. Banteng are a favorite wildlife subject and I felt lucky.

Sambar stag in a mineral lick in the interior

At noon the next day, the rangers and Thompson came to pick me up. Before leaving, we set camera-traps around the mineral deposit leaving them for a month. A young Indochinese tiger visited one of my cameras catching it in a broadside pose shown in the lead photo. This shot is one of my best tiger camera-trap captures ever, as it is close and in beautiful light early one morning just after Songkran.

Young sambar stag at another mineral deposit

Back at the station two Asiatic jackals that had been released by someone who had kept them in captivity were romping about. They have now made the area their home. I was able to get some exciting photographs of these two wild canids as they scavenged around the station. The pair, a male and female, once brought a deer leg from a carcass nearby and devoured it. They certainly have adapted to a life in the wild but are not afraid of humans.

Wild pig and piglets at a mineral deposit

A day later, we moved to a hot springs deep in the interior. Here, we photographed wild pig and sambar. As the rains have come early this year, insect activity is already in full swing. Thompson and I got out our macro lenses and had a great time chasing down the little creatures. We both photographed several new species for us including a lantern bug. The trip finally came to an end and we left the sanctuary with loads of new photographs showing the amazing biodiversity of this place.

Thick-billed pigeon at the hot spring

I know I have written many times about Huai Kha Khaeng in this column, but as the nation’s top wildlife sanctuary, it needs special attention and its continued survival cannot be stressed enough. More work is needed to improve protection with everything else taking a backseat like research and development. Ranger patrolling should be more consistent with revolving teams to create no loopholes for poachers and gatherers. Better budgets and personnel are the key.

Tree frogs mating in a pool on the road in the sanctuary

Thailand contains some of the most beautiful habitats and creatures in the world. The Kingdom is home to more than 70 million people, yet it supports an incredible variety of wildlife. However uncertain the future of the country’s wild flora and fauna may be, their presence today remains a spectacular, intriguing and mystical natural wonder.

Orb web spider at a ranger station deep in the interior

Lantern bugs at the same ranger station

*************************

Thailand’s Miniature World – Part Two

Photographing Mother Nature’s little creatures

Close-up and macro photography: Additional photographs

After more than 15 years of taking wildlife close-ups and macro shots, the following photographs are a collection assembled for this post. Some are from my old film archives and others are recent digital captures. It is hoped these images will instill upon others the positive aspect of photographing nature; whether its the little critters all the way up to the majestic elephant.

However, the message is the same: wildlife photographs are a way of expressing the need to protect and save Mother Nature’s wonderful creations through exposure, education and conservation awareness at all levels of society. The more people learn about the Kingdom’s natural heritage, the better its chances of survival into the future!

Birdwing butterfly in Lampang province

Orb spider at Angkor Wat in Cambodia

Changeable lizard in Chiang Mai province

Blue crested lizard in Salak Phra Wildlife Sanctuary

Oakleaf butterfly in Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary

Lantern bug in Chiang Mai province

Short-horned grasshopper in Chiang Mai

Bombay locust in Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary

Foilage spider in Lamphun province

Skipper butterfly in Chiang Mai province

Lime butterfly in Thap Lan National Park

Bird-eating spider in Phu Khieo

Carpenter ants in Thung Yai

Common rose and blue tiger butterflies in Thung Yai

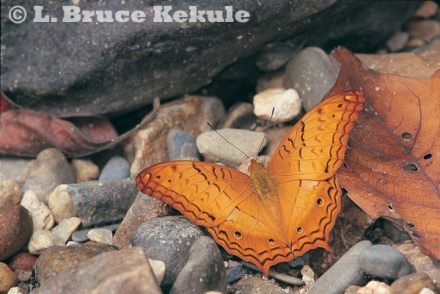

Cruiser butterfly in Sai Yok

Damselfly in Salak Phra

Dragonfly in Thung Yai

Dragonfly in Suphan Buri province

Hawk moths mating in Huai Kha Khaeng

Rhinoceros beetle in Salak Phra

Green-bellied pit viper in Kaeng Krachan

Wild hibiscus flower in Huai Kha Khaeng

Thailand’s Miniature World – Part One

Photographing Mother Nature’s little creatures

Close-up and macro photography: Intricate elements and gear

Yellow-bellied pit viper and carpenter ant in Kaeng Krachan

It is the rainy season and the day is cloudy like most during this time of the year. The rains have stopped temporarily, and the sun peeks through the clouds. Insects, spiders and other creatures such as reptiles and amphibians are extremely active in the forest when precipitation is at its highest.

While walking down a streambed in Kaeng Krachan National Park, southwest Thailand, a yellow-bellied pit viper found on a tree branch is perfect for some serious close-up photography. However, pit vipers can be deadly and extremely quick to strike.

Yellow-bellied pit viper slithering up a tree branch

I keep my distance as the serpent hangs motionless in a coiled position ready to sink its fangs into any victim. I quickly set-up my tripod and my favorite close-up rig at the time, a Minolta D7 digital camera and 200mm f 2.8 lens with a 1.4 tele-converter for an overall length of 280mm.

The most appealing feature of this lens is it can be used further away from the subject than a shorter lens, while flattening the perspective by bringing the foreground and background together. When a wide aperture is used, it will isolate the subject against a blurred background. The 280mm was also handy in the field.

Green-bellied pit viper on forest leaf litter in Kaeng Krachan

I was able to photograph the dangerous reptile from a safe distance. It was a two-day walk to the road and if bitten, I might not make it to the nearest hospital in time. Vipers are not aggressive unless provoked.

While photographing the snake, a one-inch long carpenter ant moved into the frame while I snapped a series of images. It was surely exciting, and two species in one photograph is always a neat experience. In the forest nearby, a green-bellied pit viper in fallen leaves hunting for prey is found. Pit vipers are very common in Kaeng Krachan.

Giant tree frog in a stream in Kaeng Krachan

Along this same stream a day later, we bumped into a rare green tree frog, the largest of this genus. It stayed in place long enough for some good shots but eventually jumped away. A couple days later, I also photographed a river toad further down stream.

River toad in a stream in Kaeng Krachan

While setting-up camera-traps at a mineral lick just off this same stream, a king cobra showed up. Now that was a heart stopper as the big snake rose up. I softly told everyone to stay absolutely still. It then lowered itself and slid back the way it had come. Everyone in the team had the jitters. I had absolutely no time to get any photos and was relieved the ‘king’ was gone. We decided to name this place the ‘King Cobra’ mineral lick.

King cobra hunting by the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan

However, I once photographed a king cobra near the headwaters of the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan, and managed a few off-hand close-up shots with my Minolta before it disappeared into the forest in a split-second. Some photographs are just not worth the risk but this happened so quickly that I snapped away oblivious to the danger. The undisputed ‘king of the forest’ is definitely not a recommended subject for close-up photography.

King cobra just before disappearing into the forest

When I began shooting wildlife with a camera, close-up or sometimes called ‘macro photography’ grabbed my attention. It seemed like the perfect solution to spend time when the large mammals and birds were scarce or while around camp. I reckoned Thailand’s miniature wild world was just as important as the big flora and fauna. Now, it is one of my favorite pass times. Sometimes, chasing the little creatures is not that easy and many variables come into play.

Forest crested lizard in Kaeng Krachan

My first macro lens was a Nikon 60mm that was great for flowers and stationary subjects but not very good for lively butterflies and such. I quickly up-graded to a Nikon 80-200 f 2.8 zoom with a close-up lens attachment which screws on the front of the lens. I also used extension tubes between the camera and lens. This allowed closer focusing throughout the entire zoom range. I photographed many small bugs, spiders, and other subjects of interest including flowers and natural abstracts using this combo.

Tortoise beetle in Kaeng Krachan

Since my early beginnings, I have purchased many cameras and lenses over the years. For close-ups and macro shots, I now carry my trusty Nikon D700 camera (full-frame sensor) and two lenses: a fixed Nikon 105mm f 2.8 VR (vibration reduction) and an older fixed Nikon Micro 200mm f 4. I also use a Nikon D5000 camera (1.5X sensor) with a Sigma 70-300mm Macro lens (effectively a 105-450mm) for more reach, and because it is much lighter than the D700 camera in some situations.

Champange mushrooms in Kaeng Krachan

My favorite lens now is the Nikon 200mm that I find perfect for just about everything and the focal length yields a good working distance. It allows close work on distant subjects that are skittish like butterflies, dragonflies and damselflies. Bees, hornets and wasps are best photographed from a distance for obvious reasons, as are snakes that are poisonous mentioned earlier. If the subject is stationary like beetles, dew-laden insects and spiders, flowers and abstracts, I prefer the Nikon 105mm lens.

Little map butterflies mating in Kaeng Krachan

Whenever I travel and stop by the highway for a rest or nature’s call, or when at base camp in the forest, I always have my camera and close-up lenses with me. You never know when you might bump into a good photo opportunity. This rig is also set-up with a bracket and an off-camera flash with a sync cable that is needed for certain situations. I shoot this off-hand and the flash allows stop-action and sharp images.

Thairus butterfly in a stream in Kaeng Krachan

The difference between close-up and macro photography needs to be clarified to get an understanding of the two terms. ‘Close-up’ photography is usually applied to any situation where the subject is around one-tenth of life size or greater on the image sensor or film frame. The pit viper at the beginning is classified as a close-up.

Shield-backed bug in Lamphun province

‘Macro’ photography on the other hand, is when the subject is reproduced at a magnification of life size (1:1 ratio) or greater with an appropriate camera and lens. Up to four or five times (4:1 – 5:1 ratio) is possible with modern SLR (film) and DSLR (digital) cameras and some lenses, or a combination of lenses and accessories can capture very small subjects.

Stag beetle in Doi Inthanon National Park

Anything smaller than that is possible by using a camera attached to a microscope and is classified as ‘micro’ photography. For example: a photograph of an ant’s eye, a pinhead or smaller. However, this technique is beyond the scope of this story.

Scarab beetle at the top of Doi Inthanon, Thailand’s highest mountain

To better understand reproduction ratios, the following is a simple formula to get an indication of magnification: If a 25mm-long subject is focused so that it fits on a 25mm sensor, the reproduction ratio is 1:1 or 1x; that is, it is reproduced on the sensor at life-size. If a 50mm-long subject is focused so that it fits on a 25mm sensor, then it is reproduced at half-life size, or a ratio of 1:2 or ½x. And finally, if a 12.5mm subject is focused on a 25mm sensor, then it will be reproduced as a magnification of twice life-size, or a ratio of 2:1, or 2x, and so on. A bit technical but it gives an understanding of magnification in close-up and macro photography.

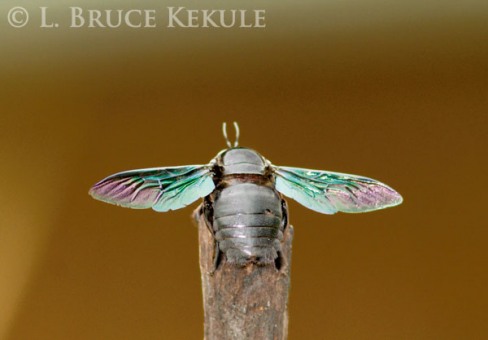

Carpenter bee landing on a perch in Sai Yok National Park

Depth of field, lighting and shutter speed is the three most important elements of close-up/macro photography. Depth of field is the zone in front and behind the point of focus that is sharp. Controlling depth of field is one of the most crucial rudiments in photography and can be checked by using a depth-of-field preview button available on some SLR and DSLR cameras. The use of the lens aperture (f-stop) and the amount of light using the ISO setting to determine shutter speed at the time the photograph is taken is important for sharp and properly exposed images.

Carpenter bee on its favorite perch in Sai Yok

There are many books and magazine stories on the subject of close-up/macro photography available from some bookstores, and these should be sought out to get a better idea what techniques and equipment is needed. Considered the ‘bible’ by many of this form of photography is a book entitled ‘Closeups in Nature’ by John Shaw, and even though this tome was written during the film era, it still teaches all the basics needed to get great shots of the small critters and their environment, and the equipment needed.

Carpenter bee in Tak province

Cameras may include some of the newer digital compact ‘point-and-shoot’ types that have close-up capabilities, and are probably the most reasonable option for beginners. The next step-up is the bridge cameras or SLR-style digital compacts. With the right accessories, close-up and macro photography is possible while the cost is still below the standard single-lens-reflex cameras that can be expensive at the pro-level.

Wood-boring beetle in Sai Yok

But the number one choice for serious amateurs and professional photographers who shoot the miniature world use a SLR or DSLR mentioned previously. There are many models and it all boils down to budget, plus the will to get the best images as the number one priority on the purchase of a camera body. Weight and bulk is also a factor. Most of the newer digital cameras are offering 12 megapixels or more.

Coppery-bordered ground beetle in Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary

If you are a beginner, there are many brands and models to choose from. It is best to check them out at your local camera store and make a choice based on your own criteria. Talk to fellow photographers for advice and read as much as possible to get an idea what you need.

Wasp spider in Thung Yai

If you are shooting a SLR-type camera, the lens and technique is very important for crisp images. Brand names lenses are expensive whereas aftermarket ones can work just as well. Again, shopping for close-up/macro equipment is a matter of choice.

Wasp spider in Chiang Mai province

Lenses for this field exist almost exclusively as fixed focal length. On image quality, they are superior to a standard zoom lens. A high-quality close-up or macro lens can be a companion for life. The focal length you choose depends solely on the type of images you want. The Nikon 105 AF-S VR previously mentioned stands out in its class, because it is the first lens to offer an image stabilizer in the macro range. Other manufactures also offer high-tech bells and whistles, and its up to the photographer to choose.

Tunnel spider in Sai Yok

Extension tubes and some tele-converters that fit between the camera and lens can increase subject size. These can be found easily in most camera shops. Another option that I like is to install a close-up lens in the filter threads of a prime lens. These are not very expensive and add very little weight. However, they are not that readily available but a few specialty firms offer them through the Internet. I use a Nikon 6T close-up lens that is no longer manufactured for both my 105mm and 200mm that have a 62mm filter size.

Tunnel spider in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

Another way to get into the macro range with a standard lens, say like a 50mm, is to install a reversing ring. Another option is to stack lenses such as a manual 200mm with a 50mm reversed using a stacking ring and this can really get down into the 2:1 to 3:1 life sizes.

Jumping spider in Khao Ang Rue Nai

Other options are a bellows unit with a lens installed either normally or reversed. Depending on the extension and type of lens used, bellows devices allow for magnification ratios up to 6:1. But this is better suited for a studio set-up.

Robber fly with prey in Khao Ang Rue Nai

A sturdy tripod and ball head is very important along with an electronic shutter release for sharp images. But they are not always practical where a tripod leg can knock foliage and disturb the subject that will fly or jump away. A monopod will control up and down movement and is easier to set in place but should be used in conjunction with a diffused flash. It is my favorite set-up when I go afield looking for miniature subjects.

Robber fly with prey in Tak province

Natural light is the best choice for close-up/macro photography but not always possible and hence, a flash comes into play. Most flashes today have TTL (through the lens) metering that allows precise flash output. Many new cameras have a pop-up flash that can also be used as long as it can be adjusted for output, and are all right for most applications but should be used with some sort of diffuser like tissue paper in several layers taped over the flash lens to avoid harsh light.

Skipper butterfly in Chiang Mai province

An off-camera flash with a slip-on diffuser plus a bracket and sync cord is tops for close-up photography. It can be adjusted for distance to subject, shot off-hand, and is quick to use. A ring flash is another option for shadow-less lighting and off-hand work.

Lemon pansi on a wild cat scat in Thung Yai

As we pass the first decade of the 21st Century, more and more people are taking up photography as a hobby or profession. The camera and lens manufacturers are constantly bringing out newer and better makes and models, and it is confusing at times.

Water drops on a plant in Eastern Thailand

However, it is an excellent pass time and the world of close-up and macro photography is only limited by one’s own imagination. Get out with camera in hand, even if it is your own back yard, and give it a try. It could become a passion and one that I am thoroughly hooked on. I hope to capture as much wildlife on digital as possible, so that others can also appreciate the wonderful world of nature in miniature.

Photographing three wild species in one day

The beginning of my 3rd book project entitled Wild Rivers

Three species on one lucky day in March of 2005

Like most of my mornings in the forest, getting out of the hammock before dawn is a routine affair for me. Sleeping by the pristine Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan National Park in southwest Thailand is a peaceful and soothing experience with the sound of rushing water flowing down to the lowlands. The night creatures fade into their abodes and daytime is greeted by singing birds and insects. As the sun comes up, gibbons call and hornbills honk from the treetops. It is nature at its very best.

Buffy fish owl by the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan National Park

I adhere to an old saying; “an early bird get’s the worm” to sometimes work wonders. This was the case one particular morning in March 2005. After a quick cup of coffee, I got my cameras ready for the days’ shoot. I was about to embark on my third book project capturing some extremely lucky wildlife photographs of three different species in one day.

The mighty Phetchaburi River during the dry winter season

About 6am, one of the Karen porters went upstream and found a buffy fish-owl stuck in his fishnets. I was upset at them to say the least but had to think quickly. The bird was going into shock as hypothermia took control over the owl. It was on the verge of dying and only quick thinking saved this creature from certain death. The campfire was going well so I placed the bird close to warm it up and get its blood flowing. I’m sure the creature had no idea what was going on but the bird was calm and collective as I assured it everything would be OK.

Buffy fish owl just after being saved from certain death

The owl began to perk up and I knew then it would survive. I placed it on a tree branch by the river and it locked its talons into the bark. The bird of prey just sat there while I played wildlife photographer. After shooting almost an entire memory card and without further ado, I left the owl in peace.

As I sat down to eat breakfast, it left its temporary perch and flew across the river disappearing into the dense forest. The bird was not seen again. I felt pleased at having saved this beautiful creature’s life. I had just switched to a Minolta digital SLR camera and was able to double-check all my shots for exposure, color and focus. Everything looked good and I was excited at having photographed this owl during the day as they are nocturnal.

King cobra hunting along the Phetchaburi River

After breakfast, we packed up our gear for a day trip headed upriver. In March, the water level is low, and the riverine habitat easy to transverse. The team and I crossed the river several times till about 4pm when I decided to turn back to camp. Just then, my research companion Detchart “Top” Saengsen sighted a large snake and called out. I reached for my camera with a 280mm lens and found a slithering black reptile in the underbrush. Its head appeared and I started shooting, not thinking about the danger. The king cobra – the world’s largest venomous snake – moved into an overhang so I flipped up the flash and took a few more shots. The reptile did a u-turn and was gone in a split second.

The big snake just before it made a u-turn and disappeared in a split second

The rest of the team had already retreated, leaving the crazy photographer to his own devices. It certainly was an exciting experience. I was elated that I had just photographed the true king of the forest. It is said large mammals like elephants, gaur and tigers stay out of the king cobra’s way. I checked my camera and had two shots left on my card. I decided not to delete any poor images until later as I felt nothing would show itself after the big snake.

Asian tapir swimming in the Phetchaburi River

The team and I were in good spirits as we headed back to camp. Suddenly, an Asian tapir bounced out of the thick forest on the opposite bank about a hundred meters away. It dove into the river and started swimming towards us, now fifty meters off. Tapir have fair eyesight but this black and white creature did not notice five humans standing out in the open up on a sandbank. I took one shot of the swimming tapir then waited, knowing very well I only had one frame left. The creature got closer and then stopped in the water about 20 meters away. I centered the focusing ring on the eye and took the shot. Then we watched this elegant animal go back the way it had come.

Asian tapir posing for me in the late afternoon sun

I know I missed quite a few shots because of old age, forgetfulness (not having spare memory cards), but then again, the two shots I had were more than enough. I was thrilled to photograph the world’s largest tapir in daylight. These creatures are mainly nocturnal and rarely seen. That day was truly the beginning of a new dream and my last shot of this tapir made the front cover of my third book Wild Rivers now published and available at bookstores in Thailand and the region. It certainly was a special day for me and one that is etched in memory.

I am now working on book four which will be a collection of stories published over a two year period in the Bangkok Post, Thailand’s number one English daily. Chapters about the top protected areas in Thailand and ‘wild species reports’ on the animals thriving in the remaining forests including mammals, birds, reptiles, insects and other categories. Hopefully, this book project will create conservation awareness among the present generation. My dream to produce wildlife books continues, but that is another story.

The Perils of Wildlife Photography

The dangerous side of a great profession

Cartoon by Smith Sutibut

Wildlife photography is one of the best professions in the world. To see Mother Nature’s beautiful creatures through the lens and then later in photographs is both exciting and rewarding. Sharing these images with other people creates conservation awareness. Not many people take it up, but those who do know the real benefits. I consider myself lucky working in the field of wildlife photography full time.

But there is a dark side. Many things in the wilderness cut, bite, sting, maim and even kill. Little insects carry diseases that can stop you in your tracks if not diagnosed in time. Such was the case when I caught Plasmodium falciparum (cerebral malaria), which suddenly became a raging infection within a couple of hours. Only a complete blood exchange transfusion saved my life.

Wild elephant feeding on discarded fruit

At the top of the danger list are animals like elephant, gaur, banteng, wild water buffalo, tiger, leopard, bear, wild boar and even male deer. In the event poachers wound any of these animals, they can be very dangerous and can easily kill humans – be they wildlife photographers, nature trekkers, field researchers or park rangers. Some animals are very protective of their young especially elephants. The tiger will also closely guard and defend their kill or their young.

Nothing is scarier than an Asian elephant in dense jungle charging with the intent of crushing you, or the roar of a tiger. Gaur, banteng and wild water buffalo – when wounded – will patiently wait a few meters off the trail and charge as you approach. Wild bovid will hook you with their horns as they pass and many a hunter has suffered a painful death. Buffalo are even worse – they will also come back to trample the intruder. The Asiatic black bear and the Malayan sun bear are fierce and will literally tear you to shreds. People would be lucky to survive an encounter with any of the large mammals.

Carpenter ants in Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary

A friend of mine in Sai Yok district, Kanchanaburi province in Western Thailand barely survived a tiger attack more than ten years ago. A young male tiger and its mother were killing cattle, taking many of the village cows and buffaloes. One day my friend went looking for the killers along a forest road. Spotting the young tiger crouching low a few meters away, he shot and mortally wounded it – but not before it pounced on him. He shoved his gun crosswise into the mouth of the roaring beast and kicked at it but he was bitten and slashed on his arms and legs. The tiger died shortly after with the gun in its mouth and my friend was rushed to the nearest hospital seriously wounded. He very luckily survived the incident but has many permanent scars. The incident made the front-page of a few Thai newspapers.

Asian wild dog in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Asian wild dog and feral dog can also be a serious menace when in large packs. A huge pack of more than 20 wild dogs in Khao Yai National Park has scared people walking on the trails. Another friend of mine who works in the park came across this pack and watched the dogs devour a sambar in one hour, bones and all. Feral dog are a nuisance on Doi Inthanon National Park, south of Chiang Mai, where a pack of some 30 dogs roam around the radar station on the peak. These dogs are killing off wildlife in the park such as deer and wild pig one at a time, and there is no telling what they might surround and eat in the future if the dog pack is not totally eliminated.

Reticulated python in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary

Snakes like the king cobra have attacked during nesting time in February if unsuspecting people find themselves between a mother snake and her eggs. I knew of a man in Eastern Thailand who failed to come home after three days. Family members found him with three puncture wounds on the head and shoulders, and his upper torso had turned black from the venom of a big snake.

I know someone who jumped off a boat wearing rubber thongs and romped in the jungle on Phi Phi Island near Phuket in the south, where he was bitten on the foot by a green pit viper. Only quick action by Royal Thai Navy personnel, who rushed the man to a hospital by helicopter, managed to save him. His foot went black and swelled up to twice its normal size. He was extremely lucky – doctors at a hospital in Bangkok saved his foot and possibly his life.

Green pit viper in Kaeng Krachan

Many other poisonous snakes can kill, if they bite you. I once had a scary encounter sitting on a chair in a photographic blind in Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary as I waited for gaur and other animals near a mineral lick. I happened to look down when a pit viper slid between my legs from behind. A natural instinct might have been to stomp on it, but I froze and the snake continued on its way. I was at least two days travel to the nearest hospital and, if bitten, would probably not have made it back for medical treatment in time.

Very mature pythons can and will, on occasion, take people. These snakes cannot differentiate between large mammals and humans that approach them. A friend of mine was out looking for bamboo shoots in the forest when a large python took his dog some 20 meters ahead. Within seconds, the dog had been suffocated and crushed to death. He looks back on the incident and says it could easily have been him. While looking for frogs one day in a forest stream, he was chased by a big python but managed to escape.

Forest scorpion in Huai Kha Khaeng

Little arthropods like spiders, scorpions and centipedes love dark and damp places. Boots and sleeping bags are inviting to these dangerous creatures. Many of them have venomous bites and stings that can become extremely serious if not treated quickly. Bees, wasps and hornets will attack intruders who walk into their space. I was stung on the back of the head by several wasps once while running in a mango orchard. Luckily, I was not allergic to their venom. A friend running behind me had to go to hospital. His head swelled up with welts where he had been stung, and he lost consciousness. But he survived the ordeal.

During the dry season, ticks of various sizes will latch onto just about anywhere on your body. Many of them have microbes that can make humans very sick, not unlike Rocky Mountain fever and Lyme’s disease. I once had a tick that clamped on to my upper shoulder while in Nam Nao National Park in Petchabun province, Northeast Thailand. By the time I realized the tick was there, it was too late. An infection had set in and my shoulder and head throbbed for many days afterward. The bite was very itchy and bothersome for more than six months until antibiotic cream finally killed the infection.

Leech in Thung Yai Naresuan

Leeches, found in many of Thailand’s forests, are a problem for photographers or naturalists wanting to romp around in the wet season. In some areas along the Phetchaburi River in Kaeng Krachan National Park, there would be 20 to 30 leeches crawling up my pants at any one time while looking for the Siamese crocodile. I was wearing high-top combat boots, leech-proof socks and tucked-in nylon pants that prevented them from getting to my legs. But some of these tenacious bloodsuckers still climbed up and got in around my waist, wrists and neck. These invertebrates fortunately do not carry a disease, although bites can stay infected for months.

Ants can also be very annoying. Some are harmless but others are downright dangerous. A single ant bite can leave a serious welt, and getting bitten by hundreds of the little creatures can quickly create a disaster. They invade clothing or sleeping areas looking for food. Some species start biting on contact with humans. The large carpenter ant about an inch long can stop you in your tracks.

Poachers with sambar antlers in Huai Kha Khaeng

Spider web is also a nuisance that you can encounter just about anywhere. I once walked into to a web and ended up with both my eyes infected for several days. Fortunately, I always carry a good supply of medicines and had antibiotic eye cream that helped kill the infection. Some microbes in water and dirt are also very dangerous and can cause intestinal and skin problems.

One of the smallest but most irritating and dangerous of all insects is the mosquito. There are more than 420 species in the Kingdom but only three species of Anopheles carry the deadly malaria. Other dangerous diseases such as dengue and encephalitis transmitted also by the mosquito can also kill.

Poachers and dog camera-trapped in Sai Yok National Park

Malaria is one of the major diseases of the tropics. There is three strains found in Thailand: Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium falciparum. The P. vivax infection can last for three years and a relapse may occur when your body’s immunity level drops. P. malariae stays with you for your entire life and P. falciparum on the other hand, strikes once and after treatment, will not return unless re-infected. All three strains have the same symptoms when infection begins, and all three are deadly.

My bout with P. falciparum was a close call. I have had P. vivax off and on for over 30 years. But this time I misjudged the infection and delayed for four days before going in for a check-up. When a blood test was taken at Mahidol University’s Tropical Disease Department in Bangkok, I had P. falciparum and about 30 percent of my blood volume was infected.

After being moved to Vichaiyut Hospital on Rama VI road in Bangkok, the infection started proliferating very quickly and rose to 80 percent by the afternoon. I was going into shock as the microbes took control of my body. Fortunately for me, the director of Vichaiyut Hospital, Dr Sompong Punyagupta, and his assistant Dr Thanomsri Srichaikul, have saved many malaria victims in Thailand with a technique called ‘Blood Exchange Transfusion’ for patients with infections of 50 percent and above of P. falciparum.

The patient’s blood is replaced with new blood at 1.5 times the person’s total volume. A special attachment is surgically inserted into the main artery in one leg, which allows the draining of old blood and the infusion of new blood at the same time. Survival rate is about 90 percent for serious cases and I thank my lucky stars that this technique was available to me. It was a close call and one that I hope will not repeat itself.

Many people ask about preventative medicine against malaria. The best prevention is not to get bitten by malarial mosquitoes, which only come out in the evening for a couple of hours and then again in early morning. Keep well covered up, use good insect repellent and always sleep in a mosquito net. All of Thailand’s border areas are havens for these deadly insects, and thousands of people die every year from these dangerous diseases resistant to medical treatment.

Some plant species can also be very dangerous. Thorns with razor-sharp points can easily penetrate clothing and skin leaving deep scratches. Sometimes the point will break off inside and quickly cause infection. Rubbing up against some plants can give you immediate pain; and if one is allergic, can turn into serious complications. Just a small amount of sap from the Sapium tree entering the bloodstream through a scratch will easily kill a human. In the old days, hunters to bring down large animals used this sap on crossbow arrow tips.

Probably the most dangerous encounter one could have is to bump into poachers, bandits or drug runners in the forest. Many National Parks or Royal Forest Department guards plus police and army personnel have been killed or wounded in the line of duty by these ruthless people. Once I was sitting alone in a photo-blind in a wildlife sanctuary at a mineral lick waiting for photographic opportunities when six poachers walked down to the water hole. Five of them had shotguns and the sixth man a set of sambar antlers.

I snapped a couple of frames, and sat motionless hoping they would not detect my presence. The spirits of the forest looked over me on that day and the group passed by without incident. It was however, a very dangerous situation and one that I hope will not happen again.

There are a multitude of other dangers that can happen in the forest, like dead tree branches falling on you or devastating flash floods during the rainy season. One could easily fall and break a leg or arm kilometers from a hospital or medical attention.

Getting lost in the forest can also make life miserable. This happened to a good friend of mine who went out for some bird watching. She and another two people were lost for several days without food and water. They became quite ill but were saved in the nick of time. Sometimes the forest can be unforgiving.

Respect for Mother Nature is important but remember, when off the beaten track, be prepared for the worst. Always take good first-aid kits, plenty of food and water, and good shelter. Know your limitations and let someone be aware of your movements in and out of any wilderness area. If you love nature, I believe the spirits of the forest will take care of you. But you should always follow the old boy scout motto: Be prepared!

Journey through a World Heritage Site: Part Six

Day 7: March 10th – Conclusion: World Heritage in jeopardy

Indochinese tiger at a mineral deposit

After all the dust had settled, I can look back at the situation in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary and honestly make an assessment of how and why this World Heritage Site is in jeopardy.

After hearing about three tigers (mother and her cubs) killed by poisoning, it seems poachers continue to enter this place and kill wild animals in the interior. A serious look at the ranger force and patrolling regimens, and the quality of protection is quickly needed before it is too late.

Deciduous forest abstract

For all the research going on in Huai Kha Khaeng, and the so-called smart patrols, how can poachers kill these rare cats? Other reports that wildlife snares and pipe-guns with trip wires are now found outside the headquarters area in Uthai Thani are alarming. These illegal hunters are slipping through the net so to speak due to too many loopholes in the patrolling and enforcement system.

In India several years ago, two national parks where researchers were working full-time had all their tigers exterminated in a year or so right under their noses. Good patrolling and enforcement is the only option when it comes to protected areas.

Deciduous flowers

Here in Thailand, most of the forest rangers are locals and hence there are not many secrets outside the sanctuary. There are 19 ranger stations that receive money amounting to 1,200 baht cash per patrol for food from the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) who also run the ranger-patrolling program. It would seem that food, clothing and equipment would be better than cash that can possibly go astray.

Approximately two times a month a patrol of five or six men spend a week walking the forests on designated trails. The poachers easily stay out of their way because they know the terrain and continue to do business as usual. It is said a bag of tiger bones now fetches more than a hundred thousand baht. Seems like a great incentive to break the law.

All patrols should originate at the headquarters and nobody knows where they are going or what trail they will take until they are already in the forest to keep leaks to a minimum. Patrol groups should be in the forest 24-7 and continue to revolve so that rangers are always out in the field.

Seub Nakhasathien monument

Without a doubt, new blood in the form of properly trained and sufficiently paid rangers using special-forces techniques is seriously needed in Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai Naresuan next door. Enforcement and arrests of perpetrators should increase and outdated laws up-graded with severe fines and detention, especially for repeat offenders.

Another very important issue is life and health insurance for the rangers in case someone is injured or killed while on duty, and this should be standard for everyone, whether government officer, or permanent and temporary rangers. A central fund should be established for this and in case of a tragedy or accident; the family will be taken care of.

Protection of this World Heritage Site is a number one priority for the government, and everything else should be second. Over the long run, good management, patrolling and enforcement is the only option to save Thailand’s natural heritage for the future.

Journey through a World Heritage Site – Part Five

Day 6: March 9th – Wild pig again, and a herd of banteng and a tuskless bull elephant pose for the camera

After breakfast, I drove a kilometer with a forest ranger in tow to look after me and parked in the forest. I thenwalked for a half hour to Huai Mae Dee, a tributary of the Huai Kha Khaeng. A permanent photo-blind is erected across from a mineral lick, also visited by all the large mammals.

After an hour and slightly down stream, a single wild pig was having a great time wallowing in the mud by the bank in the mid-day heat. After awhile, this female ungulate got closer as I continued to photograph her. It was the first time I had ever seen a female by herself. Mostly, they are in herds and only the large male boars live solitary lives.

A short time later, a fairly large herd of banteng appeared on a sandbar downstream from the blind. They were just hanging out taking in the sun’s rays and chewing their cud. The cattle then scattered as a huge tuskless bull elephant popped out on the sandbar. He was following a female, probably in heat judging from his actions. The bull did not stay long and actually came up on our side of the river disappearing into the bush, which was a bit unnerving.

At 6pm as darkness fell, our ranger came to help me carry some equipment back actually bumped into the bull elephant but it went crashing off luckily for us. At close quarters, these old cantankerous giants can be extremely dangerous to people and in fact two persons including a ranger and a villager have recently been killed by a tuskless bull in the sanctuary not far from the headquarters. It pays to stay out of their way.

Journey through a World Heritage Site – Part Four

Day 5: March 8th – Waiting on the helicopter

The next morning up at the crack of dawn, I decided to sit in the blind one last time before departing sometime in the afternoon. After an hour, a lone female green peafowl wandered into the mineral lick pecking on the ground for food and coming quite close. A short time later, a little egret also looking for food in the pond was attacked by a changeable hawk-eagle that swooped down from the trees above grabbing and knocking the water bird off its feet. The raptor hung on finally killing the egret. It was all over in a matter of minutes and the bird of prey began feeding.

Finally, the noisy chopper arrived and we piled aboard for the 20- minute ride to the headquarters. Shortly after arriving, we had lunch, and I decided to drive a hundred kilometers south and then west to Khao Ban Dai ranger station that had been our original destination for this trip.

I left after lunch and then stopped at Ban Rai, Uthai Thani for some provisions arriving at the station just as the sun was setting in the west. Dinner was made up of ‘French toast’, a specialty of mine when a quick easy meal is sufficient. Eggs, milk and some whole wheat bread make up the ingredients. The night was cool as I both slept like a log in my hammock.

Journey through a World Heritage Site – Part Three

Day 3: March 7th – Hot trek over the hills

Like clockwork, first light eventually came and after a quick cup of coffee and some breakfast, everyone packed-up their gear and headed out to beat the sun. But it was scorching hot by 10am and the dusty trail went up and down and was long as we threaded our way over the hills on a wildlife trail trodden by elephant and other large animals for millennia.

At lunch, a quick camp was erected down at the river as we all cooled off and enjoyed the refreshing water. An hour later, it was up into the hills again. The rangers attached to me got sidetracked and led us down off trail getting lost for a short period until I headed back up and found the right route. From there, we discovered a pile of gaur bones that had certainly been poached for its horns. Continuing on, we trudged along the path until the late afternoon finally reaching our number one objective as the sun dipped low.

Two large mineral licks situated by the river on either side where large mammals like gaur, banteng and elephant come for the mineral supplements. A set of fresh tiger tracks was discovered on the trail down to the deposit. The rangers quickly set-up a photographic blind in the mineral licks for me as we settled in by the river. Promptly, dinner was served and it was a quick dash to bed for most of the group after the long hot day. The excitement of finally sitting at a mineral lick I had never visited kept me up for awhile as I lay in the hammock.

Day 4: March 8th – Pigeons, parrots, and another wild pig

After that, the day passed slowly and about 4pm, a huge wild boar came to wallow in the mud and take in some vegetation staying for quite sometime. I snapped a long series of photos of the solitary pig. The rest of the day was quiet and we finally retired to the camp just before darkness.

That evening, a decision to cancel the rest of the trip was reached, and to take us by helicopter back to the headquarters due to several issues involving tiger poachers plus the extreme conditions of heat. Three tigers (a mother and two cubs) were found dead from poisoning not to far from our position. Illegal tiger bone hunters were operating in the area and the chief decided to move the group expediently away for our safety as a first priority. In the past, many rangers have been killed or maimed by ruthless poachers. Unfortunately, we would not make our destination down the river but the option to drive there was still open.

Journey through a World Heritage Site – Part Two

On the road to Huai Kha Khaeng

Seub Nakhasatien monument

Day one: March 5th

I left Bangkok slightly behind schedule but made good time as I headed northwest. After five hours of driving with a few pit stops here and there to eat, buy fuel, food and essentials, I arrived at the headquarters of Huai Kha Khaeng. As always, I paid respects to Seub Nakhasatien, a forest ranger who gave his life to nature back in 1990. This site is his spiritual home and many people visit his statue and the house where he lived, in remembrance of his sacrifice. While we were at the headquarters, I photographed a few Eld’s deer that were released into the wild around the station.

Wild boar on the run at a mineral deposit

I then drove another couple of hours going south for a rendezvous at Khao Nang Ram Wildlife Research Station. As I got closer, a huge wild boar flashed across the dirt road and disappeared into the forest giving us a bit of jolt. A total of eight forest guards including the assistant chief graciously welcomed me providing shelter and dinner. I arrived just at dusk and handed over the provisions for the excursion down the river. Dinner was served and we then watched a documentary showing wildlife and tiger research carried out at the station. Everyone retired to bed for an early wake-up.

A racket-tailed drongo by the river

Day two: March 6th – A change of plans

Our original plan was to walk from the research station across the mountains and down to the river but due to extremely hot and dry conditions in the mixed deciduous forest and the possibility of forest fire, it was decided to drive further north to the river and walk from an old deserted ranger station named ‘Yang Dang’ so we would have a good supply of water the entire length of the walk. I brought a water purification pump and we always had clean safe drinking water. This tool was simple to use and carry but extremely important for us city folk accustomed to bottled water.

Through the forest we continued west and arrived at Kabook Kabieng ranger station some 50 kilometers north. During the dry season, this part of the forest in Huai Kha Khaeng is still lush hill-evergreen. For me, this place has many fond memories of great photographic sessions.

Another wild boar at another mineral deposit

I got my first ever camera-trap photograph of a leopard on a deer kill very close to the station. On that same trip, I also photographed another leopard along the road in late afternoon from my truck, and captured a shot of a black leopard from a tree-blind at a nearby hot spring the next day. I got three leopards in two days and it still stands out as one of my great achievements as a wildlife photographer. Leopards are notoriously difficult to see and it was a lucky trip.

A black leopard photographed more than ten years ago at a hot spring

Finally, we all arrived at ‘Yang Dang’ and made preparations for the 30-kilometer trip down river. The road was rough on my old Ford Ranger but we chugged along in low gear for some gut-wrenching 4X4 driving. Unfortunately, a carry rack on top of the cab was ripped off and destroyed during the rough and tumble, and reduced to rubble.

Everyone packed up and off we went down the river. We still had to negotiate about 6 kilometers on foot to the first camp during mid-day temperatures that went past 38 degrees centigrade. It was a struggle but we made it and set-up camp by the peaceful Huai Kha Khaeng waterway just as the sun dipped behind the mountains. The water was extremely cool and it was great having a bath and freshening up for the first night by the river. Dinner was served in typical jungle style with rice cooked in army patrol pots and various Thai dishes including some hot curry. Everyone then hit their beds and sleep quickly overcame the group.