Posts Tagged ‘national park’

The Forests of Madhya Pradesh in India – Part Three

Pench National Park and Tiger Reserve

‘Collarwali’ and jackal…the little dog was faster and got away…she is old and has sired 22 cubs…but she still has class…!

In November, the weather is nice and crisp in the morning, as the winter season has just begun in Central India. When entering the forests in an open jeep, it becomes quite chilly first thing and a few layers of warm clothing are imperative. Then as the safari progresses and the sun climbs into the sky, it becomes warmer and those layers are pealed off. It’s a great time to be in the forests of Madhya Pradesh.

‘Collarwali’ on the run after the jackal…!

My time was up in Kanha, and I moved further southwest to the next great tiger reserve named Pench National Park and Tiger Reserve encompassing some 758 sq. kilometers. The taxi ride takes about three hours but is still stressful as is any two-lane highway in India. But again, I arrived in safety at the ‘Tuli Tiger Corridor’ lodge about 15 minutes from the main gate into the reserve.

‘Collarwali’ checking scent marking…!

That night before dinner, my naturalist Omveer Choudary gave me a run-down on what was going on in Pench. There was a female tiger with four cubs hanging around near the road and that our chances of seeing her was good. Also, the most famous female tiger in Pench named ‘Collarwali’ (a mother of 22 cubs) was also around. She was named because she has worn a collar for many years and the thing doesn’t even work now, but the authorities are worried about darting her with cubs and so have left it on. He said our chances were very good and this was coming from a guy who is a top-notch naturalist and driver for 12 years of experience here in Pench (he’s the boss). I was convinced.

The last time I saw ‘Collarwali’…she’s a magnificent big cat…!

The next morning after a quick cup of coffee and some crackers and cookies (standard breakfast fare while on safari in India), we jumped into the jeep at around 5am but it was not as cold as the other two tiger reserves I had just been to. We were the first in line at the gate, which was a good sign. I walked over to a ‘banyan’ tree close-by and wished for good luck. We entered but as the morning wore on, it looked like it would come-up dry.

My first tiger in Pench: She was the female with 4-cubs and it was a tight scene…!

Then, as we were more or less heading back for lunch, we bumped into a large group of jeeps parked on the road, and ‘Ome’ said, “it’s a tiger”. And there she was; the female with 4-cubs about 50 meters away from the road lying down in foliage and just her head showing. I just got glimpses of the cubs. I put a 1.7X tele-converter on my 200-400mm VRII lens to get a closer look and ripped off a bunch of shots.

Three-fanged tigress in the afternoon. She was the same tiger as in morning…!

That afternoon, we bumped into her again at another location close-by but she was still resting with her right side showing this time. Her left lower-fangs is broken. She eventually woke-up and my D3s did not stop shooting when she showed.

A sub-adult male tiger the 2nd morning…lady luck was talking…!

The next morning, we saw a sub-adult male lying down more than 50 meters away. Pench was becoming a favorite after two tigers in two days. Day three was good for other species like sambar, wild dog and jackal. And on day four at 6am in the morning we took a left turn at a junction several kilometers from the gate and all the other jeeps went straight. Around the corner and there she was: Collarwali standing in the road looking at us. Then she started walking towards us. She had her eyes on a jackal and actually chased after one but it was too quick for her. ‘Ome’ backed-up and she did not stop passing us out near the main road junction.

We followed her but the crowds began to show-up so we bugged-out. I had already got a bunch of nice shots of the most famous tigress there. I have no idea, but I really liked Pench and vowed to return again in 2016; and that is the plan for now. Jeep numbers are controlled and it is not too bad in the park like some of the other tiger reserves where it becomes a madhouse around a tiger.

Many thanks to all the staff at Tuli Tiger Corridor lodge and I would especially like to thank Omveer Choudary, my naturalist for a great time and passing on his wonderful knowledge, and to the Pench Forest Department.

Next and last stop on my journey: Satpura National Park and Tiger Reserve – where a monster croc lives…!

Kuiburi National Park: Natural evolution in Southwest Thailand

Home to wild elephant and gaur:

Elephants and gaur just after a rain in the grassland

“Wild elephants should live here in the wild, but the forest must be restored to a state in which it is able to be a source of sufficient food. We must dedicate small plots of land throughout the forest that will serve as food sources. Moreover, elephants must be protected when roaming near the forest edge.”

His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej on July 5, 1999 said on the management of the human-elephant conflict in Kuiburi National Park

A gaur bull in the grassland

Just about every afternoon, a natural phenomenon has evolved into one of Thailand’s greatest wildlife shows. A savannah or grassland situated in Kuiburi National Park in the southwest province of Prachuap Kirikhan provides a backdrop for sighting three of the Kingdom’s majestic wild animals.

Elephants, gaur and banteng seen in daylight are rare occurrences in other protected areas around the country but not here. Due to increased attention, conservation, research, funding and better protective enforcement management, the park is now world famous as a place to see these creatures. Even a tiger was recently seen here in broad daylight.

Asiatic jackal at one of eleven waterholes

This has taken place because many people now see the important aspect and value of protecting Thailand’s natural resources for the world to see. Conservation success stories are as rare as intact ecosystems and our precious wildlife. Kuiburi has become a role model for wildlife conservation in the nation.

His Majesty the King and Her Majesty Queen Sirikit have taken a special interest in Kuiburi from the early 1970s when Their Majesties provided assistance in the construction of the Yang Chum earthen irrigation dam in Kuiburi. Through their guidance in 1979, this Royal Project when completed provided access to 32 million cubic meters of water for the lowland people.

Elephant herd in late afternoon near a waterhole

After a big flood in 1996, the dam’s height was raised two meters with His Majesty providing funding to restrain more water. This was the first dam in Thailand that used earthen material from the United States to raise dam height. Water volume was increased another 9 million cubic meters and still operates to this day providing water for farming and subsidence to the people in the province.

His Majesty was also instrumental in coaxing villagers and farmers out of Kuiburi in the early 1990s, and in 1999 the protected area was finally established as a national park encompassing an area of 969 square kilometers. A large portion of the interior had already been cleared for agriculture with pineapples as the main crop plus sugar cane, vegetables, and several pine and eucalyptus tree plantations. Many people-elephant conflicts arose to become a serious problem for all. The degradation was quite severe but the park was saved just in the nick of time due to His Majesty’s efforts.

Elephant in a waterhole cooling off

Chalerm Yoovidhya of ‘Red Bull’ fame and owner of Siam Winery, has financed many projects improving the habitat for elephants and wild cattle. His first efforts were to develop firebreaks during drought periods and build check-dams in some streams to provide water in case of forest fire.

Another very important program implemented by his team and headed by Chayapol Sornsil has also improved salt licks and the grassland that attract these huge herbivores. Other programs like helping the rangers with food and equipment for patrolling has been undertaken. Chalerm recently started the ‘Thai Gaur Conservation Group’ based just outside the park. He is also organizing a foundation to help the infrastructure, up-keep of the grasslands and other important issues like the patrol rangers.

Banteng cow, mynhas and gaur in Kuiburi

Another important partner is the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Thailand who has also been very busy with many projects in Kuiburi including helping the elephant-people conflict plus doing research and camera trapping in the interior to see what has survived the onslaught of poaching and encroachment over the years. Illegal hunting still goes on but now on a very limited scale. It is a tough one to stamp out completely but under proper guidance and supervision with ‘Outreach’ programs, there is a chance for zero poaching and no encroachment over the long run. They have also been involved in the grassland, salt lick and check-dam projects.

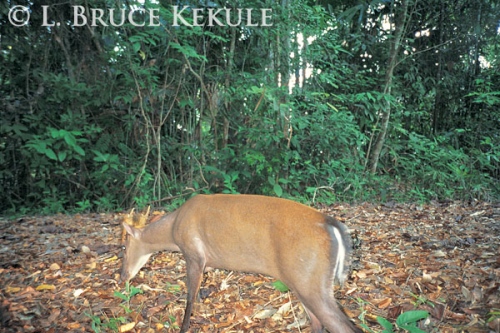

According to Dr Robert Steinmetz with WWF, there are five confirmed tigers and probably more, plus a multitude of other carnivores and prey species. Rare animals like tapir, Fea’s muntjac, clouded leopard plus Asiatic jackals, black bear, sun bear, golden cat among others has also been camera trapped by Robert. Wayuphong Jitvijak, also with WWF, has been extremely busy coordinating with the park’s personnel and local villagers on conservation, especially with the elephants.

Elephants in an old eucalyptus plantation

The most important aspect was the establishment of the grassland just a short four years ago that was compatible with wildlife. Huge areas of invasive Guinea grass (Megathyrsus maximus var maximus) that is not suitable to wildlife were removed, and replaced with Ruzi grass (Brachiaria ruziziensis), a species that elephants, gaur and banteng can live on and propagate. More than 12,000 Rai has been developed. Major funding from the National Lottery Bureau and grass seed from the Department of Livestock in conjunction with more funding from Siam Winery and WWF has been invested.

Another man has also been a very important asset for Kuiburi. He is Boonlue Pulnil, a former superintendent here who took a vested interest in the continued existence of the park. He managed to get funding to establish 11 waterholes that now provide water for the animals especially during drought periods. He still works for the Department of National Parks (DNP) and with several NGOs and groups on improving Kuiburi’s ecosystems and the wildlife. One such group is the Foundation for the King’s Wild Elephant.

Tiger photographed near the grassland in Kuiburi

Other people have taken an interest in Kuiburi’s long-term survival. The present chief of Kuiburi, Cholathorn Chamnankid is actively involved in improving protection and enforcement with a program of wildlife conservation and zero poaching. Other dignitaries include the Governor of Prachuap Khirikan, Weera Sriwathanatrakoon, who has been at the forefront of protecting Kuiburi. General Noppadol Wathanotai, advisor to His Majesty’s Projects, Office of the Principal Private Secretary is also working with the group. Kuiburi District Chief Officer Phongphan Wichiansamut, an avid nature fan, is supporting all activities on wildlife conservation and protecting the park for the future.

In July 2012, a MOU singing ceremony between the main agencies in Kuiburi including the Royal Thai Army (First Army Area of Thailand), Border Patrol Police Bureau and Provincial Police Operation Center made a dedicated effort in the province supporting the Tenasserim Agreement at Yang Chum Dam. These conservation results are positive showing a 100 percent increase in both populations of gaur and elephants. The grassland north of the headquarters is the key.

Mixed banteng and gaur herd in the savannah

Due to its status and improvement in awareness from near extinction to herds of about 250 elephants and more than 150 gaur, the road to recovery is positive. These amazing animals are now thriving very well, mainly around the savannah. Banteng however, is still highly endangered here with just a few individuals remaining including two mature bulls and one cow sighted mixing with gaur. It is hoped there are more banteng in the interior.

The need to protect these forests and wildlife in the lower Tenasserim Range is of vital importance. In the old days before roads, Kuiburi, Practakor reserved forest and Kaeng Krachan National Park to the north was all connected by naturally occurring corridor of thick rainforest along the border with Burma by these mountains.

Some 50 years ago, Thung Plai Ngam – a hunter’s paradise – was a favorite place of the rich to go on hunting trips. It is situated behind Pranburi reservoir but is now completely void of wildlife. Back then there were crocodiles in the river and large herds of elephant, rhino, gaur and tiger were common. Kuiburi was famous for its tigers in the old days.

The grassland success in Kuiburi National Park

As humans built roads and expanded into virgin forests after wood and other resources, agriculture and villages followed and replaced the jungle. All the classic Asian animals and ecosystems were systematically wiped out in man’s eager quest to survive. It is impossible to get all this back but it is imperative that the remaining patches of forest and wildlife must be saved and protected to the full extent of the law.

One of the most important aspects of wildlife conservation is to educate the people on the importance of saving Kuiburi for future generations and the world to see. Also, to keep any expansion in the park to an absolute minimum, and make sure the rangers undertake constant patrols, and arrest and put law-breakers behind bars for long periods of time. It is a fact! With zero poaching and no encroachment, the forest and wildlife will come back over time.

It now seems that Kuiburi is a special place in Thailand, and we all should be proud of the people who are or have been involved it its continued survival. They should be commended for their efforts. It has made the difference and the Kingdom’s natural heritage has recoved from near extinction to this. Finally, constant pressure must be applied to all aspects of protecting the Kuiburi forests so generations to come will see the heroes and successes of today..!

Sai Yok National Park: Home of the Regal Crab and Kitti’s Hog-nosed Bat

Amazing biodiversity in jeopardy made famous by the ‘Death Railway’ in World War II

On December 8, 1941, the same day of the Pearl Harbor attack in Hawaii (Dec. 7 in the U.S.), the Japanese Army invaded Thailand with thousands of troops and settled in. Sometime in 1942, a decision was made to build a railway from Bangkok to Burma and beyond through the thick malaria and tiger infested jungles in Kanchanaburi province using allied and Asian prisoners-of-war as construction labor.

Regal crab by the Mae Nam Noi river in Sai Yok National Park

Thousands died under the harsh and sometimes brutal conditions. Remnants of this rail line remain today in Sai Yok National Park. Numerous monuments to the men who lost their lives have been erected in Kanchanaburi, and the main cemetery in town is close to the rail line and the famous ‘Bridge over the River Kwai’ (Khwae).

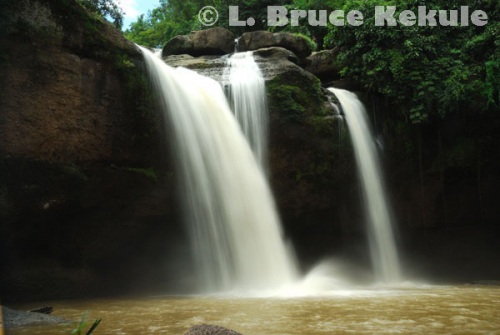

Apart from its popular waterfalls and river trips, this national park is not that well known. Situated in Kanchanaburi province, along Thailand’s western border with Myanmar, its interior is truly a magnificent wildlife paradise encompassing exactly 500 square kilometers. However, it may not remain so for long, as poaching and forest encroachment continues to be a problem for the Department of National Parks (DNP).

Kitti’s Hog-nosed bat in a limestone cave by the Mae Nam Noi

The headquarters of the protected area is at Sai Yok Yai (big Sai Yok) waterfall, about one hundred kilometers upstream from Kanchanaburi town on the Khwae Noi River. This site is visited by scores of local and foreign tourists every year that come to see the waterfall and the smaller one at Sai Yok Noi, both of which are only a short distance off Highway 323 going north. Activities on the river include swimming, rafting, boating and picnicking.

Cave-dwelling Nectar-eating bats in a limestone cave by the Mae Nam Noi

Deep inside the park, however, one of the world’s smallest mammals, Kitti’s hog-nosed bat Craseonycteris thonglongyai discovered by the late Thai zoologist Kitti Thonglongya, is found in limestone caves along the remote Mae Nam Noi and Khwae Noi rivers. Previously, it was thought to be endemic but now this creature has been found in other isolated pockets elsewhere in Kanchanaburi, and is also thought to survive in neighboring Myanmar.

Short-nosed fruit bats

This flying mammal weighs barely two grams. Aptly, it has been called the ‘bumblebee bat’ and has an average wingspan of just three inches. It uses sonar to forage for insects during short periods each night — about 30 minutes — in the evening and again for 20 minutes just before dawn. Numbers are few and is listed by IUCN as vulnerable. At one time, this remarkable little mammal was in fact one of the world’s twelve most endangered animals. Constant foraging by locals for bat dung (guano) and catching bats with mist-nets is a serious problem that needs to be addressed.

Sunset over Sai Yok National Park

Also found in this same area is the regal crab or queen crab Thaiputsa sirikit discovered in 1983 and named in honor of Her Majesty Queen Sirikit of Thailand. This crustacean is known locally as the ‘three-colored crab’. With their white body, purple stripe down the back, and red legs, the regal crab is truly a pretty sight.

Mae Nam Choan tributary in Sai Yok

They live like most crab, in holes, which they dig along the banks of the river. They come out at night to forage for food eating mainly composted leaves. Now few in number, this is yet another species that is seriously endangered and needs complete protection.

Olive-back sunbird female by the river

Fortunately, the locals in the area have stopped eating them since they were named after the Queen. They are now protecting the few crabs that are left. This is a case of true conservation and hopefully, the species will survive into the future.

Olive-back sunbird male close by

Elephant, gaur, tiger and leopard, plus many other species, still survive in the interior of the park, but all wild animals are dwindling. Sambar, serow, muntjac, tapir and wild pig are also found and constitute the main prey species for the big cats. Asian black bear, Malayan sun bear, clouded leopard, golden cat and marble cat plus many smaller species like civet, porcupine, gibbon and monkey live here but like all the rest, they too are threatened. Birds, reptiles, insects flourish as well as plant life.

Mae Nam Noi river in Sai Yok

Like most national parks in Thailand, Sai Yok is a target for poaching and logging which seem to go hand in hand. Most of the wildlife is hunted for trophies and meat, primarily during the dry season when there is good road access. It is sometimes common to see poachers in the park, cruising along the roads in vehicles or on motorcycles. Illegal logging has been carried out along the Khwae Noi, Mae Nam Noi and Mae Nam Lo rivers. This has seriously eroded their banks.

Mae Nam Lo river in Sai Yok

Other forms of encroachment include cattle and buffalo corrals that are set up deep in the forest where fodder is easily available. The chance of ‘foot and mouth’ disease being passed on to wild ungulates is real. Fruit orchards pop up in areas along the river inhibited by wild creatures and seem to thrive. Constant illegal activities are affecting the status of the park’s wildlife and watershed integrity.

Leopard camera trapped in the interior of Sai Yok

The forests in Sai Yok are mostly tropical broad-leaved evergreen with much bamboo and mixed deciduous woodlands in the foothills. The highest peak, Khao Khewa, at 1,327 meters above sea level, is part of the Tenasserim Range that runs through the park from north to south. The area was formerly logged so the park has many thin patches where big trees were felled. However, heavy brush continues to grow back strongly in these areas.

Elephants camera trapped by the river

During the height of the rainy season, between July and October, Sai Yok’s wildlife roam and feed fairly safely due to the rough weather and almost impenetrable terrain. The rivers and streams in the park become raging torrents that make crossing them next to impossible. About the only way in is by long-tailed motorboat, with a very skilled operator.

Mae Nam Lo river deep in the interior

Many a boats and rafts has been washed away in rapids on the Mae Nam Noi and Mae Nam Lo rivers. Occasionally, 4×4 off-road vehicles become stuck in the park after heavy rains. Some have even had to wait until the dry season to get out. Elephant just love to play football with these vehicles left behind. I know a man who left his Land Rover through the rainy season and when he returned, it had been flipped over and completely smashed.

Crab-eating macaque by the Lo River

Another very important aspect of Sai Yok is that gaur and elephant come across the border from Myanmar to feed on bamboo shoots in August and September, and then return to the safety of the other side prior to the dry season. Equally interesting, there are unofficial reports of a ‘hybrid cattle’, possibly a cross between gaur and banteng that have been seen by locals.

Young crab-eating macaque with a troop

The numbers of all animals are dwindling, however, due to increased activity in the park. Just a decade ago, green peafowl were found here but they have neither been seen nor heard from for many years. The ever-shrinking wilderness area of Sai Yok is under threat that should be addressed by the DNP if its flora and fauna are to survive intact.

Mae Nam Choan river

Sai Yok has always been special to me. I basically began my career as a wildlife photographer here after making a promise to the ‘spirits of the forest’ to begin documenting Thailand’s wildlife with a camera. Some of my first photographs are the regal crab and the Kitti’s hog-nosed bat shown in the story. I also camera trapped my first and second tiger in the interior. I recently caught a leopard by camera trap along a trail by the river seen here.

Khwae Noi River in Sai Yok

The future of Sai Yok as one of Thailand’s most beautiful and important national parks depends in great measure on the DNP and their ability to enforce the law. Reportedly, greater efforts are being made by the department to protect the park and its precious wildlife and ecosystems. Some poachers and encroachers have been arrested but such campaigns can be difficult to sustain. The long-term effects will become clear over time.

Candlebra bush flowers in the interior

It is hoped this magnificent wilderness and its wildlife will survive into the foreseeable future. In particular, the home of the world’s smallest bat needs serious attention and protection. It would be a sad day for Thailand if this prestigious mammal were to be lost to extinction.

Keang Krachan: Rare creatures surviving in the park

A collection of photographs taken from 2001 to 2008

of some rare Asian animals still thriving in this amazing forest

Fea’s muntjac camera-trapped at Kilometer 33 on Phanern Thung mountain

Male muntjac also known as common barking deer at a mineral lick

Male muntjac feeding on leaves

Gaur cow at a mineral lick in the interior

Small gaur herd at another mineral lick

Gaur bull and cow footprint compared to my hand

Asian tapir swimming in the Phetchaburi River

Tapir camera-trapped near the Phetchaburi River

Serow camera-trapped on old logging road

Tusker camera-trapped at a mineral deposit at kilometre 12

Tuskless bull elephant in ‘musth’ camera-trapped on an old logging road

Tiger camera-trapped at a mineral lick in the interior

Indochinese tiger camera-trapped by the Phetchaburi River

Asian leopard camera-trapped on a nature trail

Indian civet caught near Ban Krang campground in the park

Banded linsang camera-trapped on a dry streambed

Banded palm civet camera-trapped by a stream deep in the interior

A king cobra hunting for prey by the Phetchaburi River

A green pit-viper and carpenter ant on a small tree

A green pit-viper swallowing a skink

Reticulated python on the road in Kaeng Krachan

Horny tree frog in a stream deep in the park

Giant tree frog further upstream

Great hornbill flying out of a fruit tree

Oriental Pied hornbill feeding its chicks at the nest

Wreathed hornbill at a nest

Oriental dwarf kingfisher near it nest

Pied kingfishers with a fish on a tree branch

Blue-bearded bee-eater with a beetle for its chicks

Red-bearded bee-eater close to its nest in a sandbank

Black-and-red broadbill with a bamboo leaf

Black-and-red broadbill building a nest

Javan Frogmouth by the Phetchaburi River

Lesser fish-eagle chick exercising its wings high up a very tall tree

Lesser fish-eagle mother and chick on the nest above the Phetchaburi River

Lessor fish-eagle on a tree branch behind my blind over the Phetchaburi River

River carp in the Phetchaburi River

Gibbon hanging from a bamboo on Phanern Thung mountaintop

Dusky langur near the Phanern Thung ranger station

Stumped-tailed macaque by the river

Rainbow over the Phetchaburi River

Kaeng Krachan National Park is an amazing place but is fraught with poor management and protection. There are many other animals and ecosystems not shown here but this place is truly one of Thailand’s greatest protected areas.

It takes lots of hard work to get down to the river and collect photographs of the creatures thriving there. But diligence, determination, the right equipment, money and with good guides, is also within the reach of serious amateur photographers or naturalists who just want to look.

The opportunities are endless. It is hoped these photographs will create awareness and help this place survive into the future, so that generations to come can also enjoy the beauty of nature in Thailand’s largest national park.

My next post will be a collection of photographs from Huai Kha Khaeng like this of that amazing World Heritage Site, and hopefully sometime before I travel to Africa for a safari to Kenya in mid-August.

Phu Khieo: Saving a species

Land of the plateau – pristine forest in the Northeast

Hog deer haven and introduction site

On Thai wildlife day, December 26, 1983, Her Majesty Queen Sirikit released four hog deer made up of two mature males and two females in breeding age at ‘Thung Kamang’ grassland in Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary situated in the northeastern province of Chaiyaphum. This was the beginning of what is now a successful introduction program in order to save the species.

Hog Deer on the run in Phu Khieo Wildlife Santuary

The Crown Prince in 1987 introduced another four hog deer, and reintroduced several male and female sambar (Thailand’s largest deer) in the same area. In 1992, Her Majesty the Queen once again released more hog deer to boost the numbers of the herd. She also released three Eld’s deer (one male and two females). Unfortunately, this species has been difficult to monitor because of their preference for deep forest unlike the hog deer that prefer grassland and swampy habitat.

Phu Khieo massif

Over the years, the herd of hog deer has steadily increased due to a safe haven away from poachers and encroachment. In 2004, there were approximately 75 deer, and in May 2008, Kasetsart University conducted a survey around the grasslands and headquarters area counting more than 120 individuals. There are now approximately 140 hog deer in three or four separate herds. The sanctuary officials are constantly monitoring the herd with six hog deer fitted with radio collars and have established their range in the sanctuary.

It’s November and not a single cloud can be seen in the clear blue sky. Early morning air is crisp and cool. Heavy dew blankets Phu Khieo as mist rises from the forest. The sun arcs up into the sky and morning heat builds up. A mature sambar stag barks a warning call alerting all the animals within audible range that a predator is on the prowl. In the grasslands, a herd of hog deer grazing on tender young shoots is now on high alert. They are nervous and begin moving as the top carnivore of this forest stalks them.

Sambar yearling doe in late afternoon light

A pack of hungry Asian wild dogs working like a well-oiled machine concentrate on their target. They bump into the deer scattering them. The dogs go after an inexperienced doe and separate her from the herd. The chase is on. The deer becomes confused and makes a wrong turn. The dogs pull the struggling creature to the ground and go in for the kill. Within an hour the carcass is stripped and almost nothing is left except a few scraps. But it’s just another day in the balance of nature where natural selection and the struggle for life and death between predator and prey is played out.

In the early 1830s’ during the reign of King Mongkut, the French missionary Monsignor Jean-Baptiste Pallegoix, in his excellent book entitled ‘Description of the Kingdom of Siam’ published in 1850 reported seeing large herds of deer grazing on the central plains. Hog deer were still quite common in the Kingdom even at the turn of the 19th Century and could be found in all the river basins of the far North, the Northeast, the West and the whole of the Chao Phraya River basin and its tributaries. Hog deer fossils taken from sand dredging in many rivers dates back thousands of years to the Holocene, and teeth fossils of hog deer were discovered in a cave in Phu Khieo dating to the Pleistocene.

Hog deer buck and doe – the male has a radio collar

Unfortunately, these lowland deer were totally overcome by habitat destruction converting natural grasslands and swampy areas into agricultural land throughout the hog deer’s former range. Hunting deer was also a big business and warfare in Asia drove the skin trade. From the late Ayutthaya Period up to the early 20th Century, Siam exported millions of deer pelts from all the large species of deer including Schomburgk’s deer (extinct), sambar, Eld’s deer and hog deer to Japan. Deerskin being soft and supple was used to make leather for Samurai armor and clothing, boots and equipment mostly for the military. This was one of the main reasons for the disappearance of these remarkable creatures from the wild.

Short-nosed fruit bats

Captive breeding of hog deer, Eld’s deer, sambar and muntjac (barking deer) is carried out in some of the 22 wildlife breeding centers around the Kingdom set up by the Royal Forest Department, and now managed by the National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department (DNP). The Phu Khieo Wildlife Breeding Center outside the sanctuary has been active since 1983 and is still breeding deer and wild pigs for future release into other wildlife sanctuaries and national parks.

Essarn is not all barren and dry like many people think. Over in the western part of the Northeast is Phu Khieo – Nam Nao Forest Complex that incorporates 19 protected areas, covering some 7,725 km2 (twelve national parks and seven wildlife sanctuaries) in the provinces of Chaiyaphum, Khon Kaen, Nong Bua Lum Phu, Udon Thani, Loei, Phechabun and Lop Buri. The complex incorporates a number of large forests on the Phetchabun and upper Dong Phayayen ranges. Phu Khieo, established in May 1972, is the largest sanctuary in the complex at 1,560 km2 made up of, a rocky plateau and steep mountains. The protected area is covered in forests of pine, deciduous, dry dipterocarp and evergreen with many streams that flow into the Chi, Lam Phrom and Sa Phung rivers.

Bird-eating spider

Phu Khieo has elephant, gaur, sambar, muntjac, mouse deer, tiger, clouded leopard, golden cat, back-striped weasel (extremely rare), black bear, gibbon, langur and macaque plus many other mammals can still found here. Jeffery McNeely found tracks in 1977 of the Sumatran rhinoceros on a mountain in the middle of the sanctuary. The last set of rhino footprints was recorded by the sanctuary staff some 10 years ago but has not been seen since. Crocodiles are thought to lurk in the backwaters but again, only footprints and feces have been discovered several years ago. These two species need further investigation and research to establish if they still exist, especially the rhino.

Rare birds such as the Oriental darter and white-winged duck live in the secluded wetlands found in this forest. Other birds include hornbill, osprey, black baza, blue pitta, Siamese Fireback, plus loads of babblers, flycatchers, barbets, kingfishers and other forest birds. The very rare purple cochoa has been sighted and photographed here.

Oriental Darter by the lake

Much research has been carried out by foreign and local researchers from various organizations. Stonybrook University in New York sent a team to monitor and record behavioral habits of the Phayre’s langur and crab-eating macaque. Lon Grassman, as a master student with Kasetsart University, did a camera-trap survey and, collared golden cat and clouded leopard plus other carnivores with support from Texas A&M University and he received his PhD from this excellent work. Kitti Kreetiyutanont who heads the Phu Khieo Research Station has done much research on biodiversity of flora and fauna found here, and in the buffer zone outside the sanctuary. He also has done some archaeology work finding pottery and tools thousands of years old. There are some cave drawings in the sanctuary indicating past civilizations. Wanchnok Suvarnakara, the deputy superintendant, is an avid wildlife photographer and has recorded many species on film and digital, and published a photographic book.

Pansi butterfly

For the first time in the history of wildlife sanctuaries since Salak Phra in Kanchanaburi was established in December 1965, a woman has been nominated as superintendant to Phu Khieo. Dr Kanjana Nitaya received a doctorate on management, and has run this protected area with determination to succeed. The staff and locals who have benefited from her management skills and leadership over the last four years respect her. In 2006, Phu Khieo was voted as the best wildlife sanctuary in all categories by DNP due to criteria established by the department. She is proud of this achievement and hopes this will help the conservation of this magnificent place well into the future.

Bombay locust

However, poaching and encroachment is still an on-going problem for the staff. Another serious long-term idea from politicians in the lowlands is to build a dam across the Sa Pung Nua River on the southern face of the plateau not far from Nong Bua Daeng in Chaiyaphum. If this dam were to become a reality, a large swath of forest would be inundated and damage the ecosystem already in jeopardy. All efforts should be made to stop this project before it goes too far. As Thailand’s best wildlife sanctuary, it should not be compromised by the construction of a man-made scheme.

Saving a species from extinction should be a top priority of the DNP. Other ungulates like goral, serow and banteng should be reintroduced into protected areas where they once thrived. Some may argue against introduction or reintroduction, but as we loose more and more species, release is a practical way to save Thailand’s rare animals from extinction in the wild. It is up to the department to instigate and increase these introduction/reintroduction projects, and then to protect these animals from danger by all means available. Budgets for enforcement and protection need to increase, and more staff to man any project to save a species from extinction is an utmost priority.

Hog deer buck in the grassland

Historically, the range of the hog deer spread from India and Nepal, east through Burma and Thailand, to Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. This deer is now restricted to just fragments of its former range. In Thailand, the last sighting of hog deer was in Nong Khai province in the Northeast sometime during November 1963. There are some hog deer herds in the wilds of Cambodia and Laos.

Hog deer were typically found on alluvial plains and lowland forest along rivers, particularly near marshes with tall grass. Today it would be impossible to reintroduce these deer into any of their former habitat, but a few protected areas like Phu Khieo are ideal. Any introduced or reintroduced species needs the full protection afforded by a national park, wildlife sanctuary or non-hunting area.

Hog deer are medium-sized animals that resemble the larger and more common sambar deer in appearance. Male hog deer antlers are similar in shape as sambar but smaller. Depending on the season, they have grayish to dark brown fur. Females like all other deer species, have no antlers. Fawns have spotted coats. Spots can also be clearly seen on some adults.

These deer are more of a grazer than a browser and feeds on grass. They are gregarious, forming large family groups. The rut starts in September and goes on through October. A single fawn is born eight months later, during the rainy season around July or August. Hog deer received their name because of the way they move. Unlike other deer, they seldom jump over a bush or high grass, but they tend to run through the underbrush with head held low to the ground, much like a hog.