Posts Tagged ‘Huai Kha Khaeng’

Red Jungle Fowl – Wild ancestor of the domestic chicken

WILD SPECIES REPORT : Endangered Asian Galleopheasants

Red jungle fowl in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

It is 3am in lowland dry evergreen forest of Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary in eastern Thailand. Close by, a familiar sound is heard waking me up from sleep in my hammock. I’m at the wildlife research station close to the headquarters area of the sanctuary during the breeding season. A male red jungle fowl Gallus gallus has just emitted the well known ‘cock-a-doodle-do’ on the hour as its kind has for thousands of years.

These birds are quite common in Khao Ang Rue Nai that borders Khao Soi Dow Wildlife Sanctuary in the Southeast, and is a haven for this Galleopheasant. It has been determined the species is the ancestor to the domestic chicken.

Red jungle fowl male taking off from tree branch

After a quick cup of coffee, I ready my photographic equipment and head out into the bush about 6am at first light with my main lens and camera mounted in the window of my Ford pick-up. I have photographed many animals this way by driving around and when a subject is found, my camera is ready for instantaneous use. As long as I stay in the truck, it is possible to catch many birds, mammals and reptiles in their natural environment.

On this particular morning as I was on the road near a man-made reservoir in the protected area, the sun was just peaking over the distant mountains when I flushed a male and female jungle fowl. They flew to a tree about 50 meters away and stayed for a short while as I fired off a long series of photos. But the male was seriously in love and did not pay me any attention as I edged the truck closer for some full-frame shots of the pair. Then the female took flight, and the cock-in-love chased after her but I was ready catching him in mid-flight just off the branch.

Red jungle fowl male with leg band

A close look at the lead photograph will reveal a band around the male’s left leg. This bird was part of a scientific survey carried out by my very close friend and associate Dr Sawai Wanghongsa, and his staff at the wildlife research station at Khao Ang Rue Nai. The rooster was three to four months old when captured about 500 meters away the previous year, and was now full grown and breeding when this photograph was taken in 2009.

But the amazing thing, I could read some of the numbers on the band after enlarging to extreme size in the computer shown in the inset, and Sawai correlated his data about this particular bird. It certainly was a lucky set of photographs including the flying shot of the wary jungle fowl. He has written several scientific papers on the species.

Red jungle fowl in Huai Kha Khaeng WS – A band of cocks

Two sub-species of red jungle fowl live in Thailand. Gallus gallus spadiceas is found on the western flank from the North all the way down to Malaysia, and in the east lives G. g. gallus. The only distinct difference between these two is a white spot on the ear pad belonging to the eastern species, and a red pad on western birds.

Dr Sawai works for the Department of National Parks and collaborates with Japanese scientists including H.I.H. Prince Akishino-no-miya Fumihito of Japan who is studying the relationship between red jungle fowl, domesticated chickens, and the impact humans has upon the wild species. Dr Yoshihiro Hayashi and others with the University of Tokyo and Professor Wina Meckvichai with the Department of Biology at the Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok are also involved in the project.

Red jungle fowl male and females in Huai Kha Khaeng WS

Between 2005 and 2009 they conducted intensive research on the ecology of red jungle fowl in Thailand for the royal multi-disciplinary research project entitled ‘Human-Chicken Multi relationship Research Project (HCMR)’ initiated by Prince Akishino under the royal patronage of H.R.H Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn of Thailand.

They concentrated their studies in Wat Prathat Mae Jedee in Wiang Papao district of Chiangrai province, northern Thailand where the red ear-lobed jungle fowl thrives in strips of forested areas sandwiched between temples and villages where domestic chickens are raised. Parallel studies were also carried out in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife, where the white ear-lobed jungle fowl exist but are more isolated from villages and people. They have gained much evidence about the domestication of chickens. A new program is now underway to further their knowledge and understanding.

Red jungle fowl in Khao Ang Rue Nai WS infested with ticks

Charles Darwin in 1875 speculated that red jungle fowl was the wild progenitor of all domestic chickens and proposed that Southeast Asia was the origin of domestication. Later, genetic evidence supported the Darwin hypothesis in that this species was the main ancestor of domesticated chickens (Fumihito et al. 1994, 1996), and domestication took place somewhere in Southeast Asia, especially Thailand and neighboring areas some 8,000 years ago. Cave paintings revealed chickens were portrayed on a single cave wall in Khao Pla La, Uthai Thani province dating back 2500-3000 years ago.

Prince Akishino was recently in Thailand and granted a Royal Audience by H.M King Bhumibol Adulyadej. Then, the Prince visited Department on National Park (DNP) officials including Sunan Arunnopparat, the Director General who presented a framed copy of the lead photograph to the Prince. It was certainly a great honor for me as the photographer.

Red jungle fowl in Khao Ang Rue Nai WS infested with a tick

Another interesting set of photographs I acquired in Khao Ang Rue Nai of red jungle fowl is a rooster infected with ticks with a large tick on one side latched on to his waddle, and a smaller tick with a load of little ticks on the other side. Males normally have a red crest but this bird looked like it had lost most of its color and was seemingly rather pale.

This was during the dry season and ticks are everywhere latching on to anything that provides blood. It definitely is a dangerous time for human beings as some ticks have harmful viruses that can make one very sick, and has killed people that contracted Lyme’s disease through tick bites. I dread the little critters and get rid of them as soon as possible if they latch on to my skin. I once had one on my left shoulder after visiting Nam Nao National Park in Phetchabun province that became really infected before I got rid of it, and the swelling and itchiness lasted for months.

The Prince of Japan being presented a framed photo by the Director General of the Department of National Parks

Over on the western side of Thailand in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, red jungle fowl are also very common in this World Heritage Site. I am sitting in my battery powered boat-blind up-river about five kilometers from the southern boundary at Krueng Krai ranger station. The sun is bright and warm on this chilly morning. A red jungle fowl male and his harem of two females are pecking the ground for food by the waterway.

I slowly and silently ease the boat closer to get some frame-filling shots of the group. Again, the cock was only interested in the hens and I was able to get quite close. These birds are normally not that easy to photograph.

Prehistorically, the genus Gallus was found all over Eurasia. In fact it appears to have evolved during the Late Miocene/Early Pliocene of Greece and surrounding areas. Several fossil species have been described, but their distinctness is not firmly established in all cases.

As this is about red jungle fowl, the other species like grey jungle fowl G. g sonneratii surviving in India, the Sri Lankan jungle fowl G. g. lafayetii coming from the island of the same name, and green jungle fowl G. g. varius from Indonesia are related.

Male jungle fowl have gaudy iridescent colors but the females come with subtle browns and grays for camouflage. The male have a white rump and legs are grey. The species is found in a wide variety of forest types.

During the breeding season, the dominant male will crow (also known as ek-ee-ek-ek) every hour on the hour. Out of breeding, they only call twice a day, once in the morning and again in the late afternoon. Males form harems in December, and breed from January to May. They nest on the ground and have a clutch of eight to ten eggs. After two months, the chicks will disperse.

The domesticated chicken G. g. domesticus is only mentioned in passing for this story. They of course provide humans with meat and eggs that make up one of our most important protein diets. But now domesticated chickens in close proximity to wild birds have created genetic problems that have arisen in forest jungle fowl at certain locations around the Kingdom.

Nowadays, chickens are involved in many aspects of the normal life of man. Chickens are involved in religious ceremonies as a sacrificial animal, in games as in fighting cocks, in leisure activities as pet bantams, and in the commercial poultry sector as boilers and egg layers. It has been estimated that by 2020, some 83 million metric tons of poultry will be globally consumed every year.

Cock fighting as practiced in the South of Thailand uses specially made daggers that are attached to the rooster’s spur. These extremely sharp weapons are made only from serow horn that has greatly affected this goat-antelope once found in just about every mountain in the Kingdom. Due to hunting for meat and their horns, these unique wild ungulates have also become seriously endangered.

Red jungle fowl is now on the endangered list, and the species like all the rest of the animals living in Thailand’s protected areas need absolute protection. Sweeping changes are needed in its implementation. It seems though the long hard struggle to protect the Kingdom’s forests continues to be an up-hill battle, not only for the DNP, but all the other conservation minded people who love nature. The future of wildlife and the forests remains unclear, and increased budgets, more personnel, better management and education to all levels of society are the key!

The Asian Leopard: Thailand’s second largest cat

WILD SPECIES REPORT

An ambush predator – solitary, stealthy and naturally camouflaged

The late French poet Robert Desnos (1900-1945) wrote a short poem entitled “The Leopard”

“If you go into the woods, beware of the leopard.

He meows in subdued voice and arrives from nowhere”

Black leopard in the late afternoon sun

The leopard Panthera pardus described by Linnaeus in 1758 is the second largest cat in Thailand. Once upon a time, leopards could be found in all the forests of the Kingdom. These felines are still surviving quite well in protected areas in the West, and some in the South. The central, eastern and northeastern regions have no reports of leopard for some time now.

A few have been reported in Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary in Chaiyaphum province, but for some reason they have disappeared from most remaining forests. The reason these areas have no leopards are quite simple; prey species has been hunted out including the leopard itself for its pelt and bones, and encroachment has destroyed much of its habitat.

Sighting a leopard in Asia is extremely difficult, and even catching a rare glimpse of this very essential top predator is tough due to its solitary and stealthy behavior. However, luck can sometimes play an important part in viewing the leopard and I feel lucky to have seen and photographed them on quite a few occasions.

Leopard camera trapped in Kaeng Krachan National Park

The most thrilling or heart stopping adventure with a black leopard happened in Huai Kha Khaeng about five years ago while I was sitting up on a bluff overlooking the river. A photographic blind was erected on the rock-face about 20 meters up with a small trail that enabled me to get into the hide. It was a neat location that I had dreamed of sitting here for many years prior. The sun was bright and the weather was warm during the dry season.

About 9am, several monks down by the river passed on but did not see the camouflaged structure as they went their way. After that, I came down for lunch and set some camera traps at a mineral deposit nearby. At 2pm, I settled back in the blind and began a vigil of the river. I started to feel a bit groggy as the sun was beating down on my position. I moved my camera in to save it from the direct sunlight.

All of a sudden, I was startled by a guttural growl outside the enclosure. I stood up slightly and peering out the window came face to face with a huge round black head and yellow eyes about two meters away that penetrated my soul. My first instinct reaction; it was a big black dog. But that quickly changed as the creature stared intently at me before bounding down the trail it had come up. The big cat was gone in a split second. Of course there was not enough time to get any photographs. The incident surely is etched in my memory.

Black leopard camera trapped in Kaeng Krachan

Why had the leopard come so close without smelling me? On that particular day, I was using an old hunters technique by collecting fresh wild water buffalo droppings and putting them in front of the blind, and that probably covered my scent. Maybe the leopard thought there was a newborn calf, or an old weaken animal. Or maybe it used this natural place overlooking the river to spot prey like sambar, barking deer or wild pigs that are abundant here and came up to investigate. The vantage point is on a bend in the river and one can see for quite a distance both ways.

I will never know how close I came to being attacked by a leopard but it was a heart stopper for sure. I sat motionless for quite sometime. Only a few sticks and camouflaged material separated me from a wild creature armed with fangs and claws. On that day, the spirits of the forest looked after me, or was it the ‘Spirit of the Forest’. I like to believe that was the case. I hope one day to go back and stake out this bluff, and believe this leopard is probably a resident around here. Previously, I camera trapped tiger and a yellow phase leopard not far from here.

A leopard resting on a wildlife trail

Speaking of leopard attacks, my close friend and associate Dr Lon Grassman was once seriously injured in Kaeng Krachan National Park, Phetchaburi province by a leopard while working there on a survey to camera trap and collar the big cat. When Lon released one, it looked up and turned on him in a split second mauling his legs and arms. It was a close call but he survived to carry on his work researching wild carnivores. Lon established the home range and other behavior patterns of leopards in the park.

He then moved to Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary, Chaiyaphum province in the Northeast and continued this work catching and releasing quite a few golden cats, clouded leopards and a marbled cat. He eventually received his doctorate for his excellent work.

In the beginning of my profession as a wildlife photographer, I was very fortunate. The Director of the Wildlife Conservation Division of the National Parks Department (DNP) at the time, my dear friend Dr Viroj Pimmanrojnagool (now retired), had confidence in me and gave permission to enter the realm of the leopard and the tiger, something not easily acquired. Entry into wildlife sanctuaries has always been very restricted but is possible with the right qualifications. Viroj and I are still very close and I visit him from time to time at his durian farm in Surat Thani down south where he is happily enjoying retirement.

Leopard in the bamboo – my very first photo of the big cat

My first encounter with the sleek cat goes back to the beginning of my career more than a decade ago. Driving into the forest late one afternoon in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, a World Heritage Site, the sun was low but the light still quite good for photography. The protected area is situated in Uthai Thani province and is part of the Western Forest Complex.

I was about to capture my very first Asian leopard on film. This was in my early days as a wildlife photographer with a newly acquired Nikon N90s camera and 300mm lens. I was on a learning curve that would take me into some unique natural habitats and bump into some very unusual animals around Thailand.

Leopard posing in Kaeng Krachan

About 4pm some 10 kilometers from the headquarters as I was driving in, a leopard jumped in front of my truck and bounded up the steep embankment on my right. I gently came to a halt and there looking down at me was these two big yellow eyes that brought my attention to 100 percent. In the meantime, I had already grabbed my camera and started snapping through the window as fast as possible but quickly slowed the pace concentrating on focus. After a few more shots, the spotted cat melted into a bamboo thicket and was gone. The encounter was measured in mere seconds.

I sat in the vehicle for a few minutes to catch my breath as my heart was thumping. A close encounter with a carnivore capable of tearing us apart is something that can get the blood flowing. I finally got going again as my destination was still a couple of hours away deep in the forest.

Leopard on a sambar kill – my first camera-trap photo of the feline

Arriving at the Kabook Kabieng ranger station just at dusk, the head of the station Loong Waitanyakarn, another good friend, came immediately to the truck and said, “ a sambar mother and fawn have been killed by a leopard or wild dogs not far from the station and let’s go look”.

It didn’t take me long to ponder that an opportunity had presented itself. I had a new infrared sensor for my Nikon camera and decided to set-up the unit next to the dead sambar. A new role of film was loaded and the lens focused on the mother deer. The sensor was active infrared that uses a transmitter and receiver hooked to the camera. When an animal trips the beam, the shutter is activated taking a self-portrait. At the time, this technology was rather new but I needed it to supplement my regular photography.

Black leopard posing for me at a hot spring

The next day at noon some 10 kilometers away, Loong took me to a tree stand over-looking a hot spring. The box-like structure was quite high up and it was a bit scary getting situated in the blind but finally, I settled down with my Nikon 500mm lens and camera scheduled for a three-day stint. The mineral deposit and hot springs attracts many large mammals including elephant, gaur, banteng, tiger, leopard, wild dogs, tapir and many other animals that come for the life-giving minerals, or for prey.

Black leopard at the hotspring

About 3pm, a troop of leaf-monkeys visited the hot springs for a quick drink but did not stay long. They had been spooked by something as they all panicked and gave flight in the trees up the hill. A short time later, a black leopard appeared from the top end and walked over to where the monkeys had just been. The sun was low in the sky and I could see the leopard’s pattern of rosettes through the lens that jumped out at me.

My heart began racing as the stealthy cat stopped at the top to take a drink. It stayed for about an hour. I calmed down but continued shooting changing several rolls of film and watching this magnificent creature. Just before the sun was gone, it moved closer to the tree I was in and then walked across the stream. The cat plopped down on a log and stretched out posing for me, all the while looking up at my position. I kept shooting and then it came even closer before veering off probably spooked by my scent. As the leopard moved through the forest, monkeys, barking deer and sambar barked at the predator.

Leopard mother and cub camera trapped at a sambar kill – A rare photo

showing both color phases

I will never forget these encounters. Three leopards in two days are pretty good going for a new wildlife photographer and it was truly the beginning of many sightings and photographs of this amazing carnivore. I have seen loads of them on film while working in Kaeng Krachan. Both black and yellow phase were camera trapped in three separate locations in the interior at almost every location.

The Tenassarim Range in southwest Thailand is an absolute haven for the leopard due to a very good prey base here. Tigers also survive and have overlapping territories with the spotted cat. Both species hunt during the day and night. My old friend Suthad Sapphu, a forest ranger in Kaeng Krachan, was extremely helpful while we were camera trapping the big cats.

Leopard track in Kaeng Krachan

Without doubt, the future of the leopard depends on one thing only – the complete protection of the remaining forests where they live. If the national parks and wildlife sanctuaries remain intact with a high number of prey species, the big cats will survive. But if over-development, poaching and encroachment are allowed to continue, the large cats will eventually disappear.

Unfortunately, too much time and money is wasted by too many organizations talking about saving wildlife and their habitats, with very little actually being done. Human population growth will eventually destroy most wild places. Only true protection by some dedicated people will slow the destruction of nature’s precious wildlife and wilderness areas. It is hoped the leopard, and the tiger, will continue to survive as they have for millions of years.

Leopard Ecology:

Pound for pound, the leopard can take on some seriously large animals several times its size. The leopard is closely related to the jaguar of South America. Both have a spotted coat pattern, incidence of ‘melanism’ or black phase, and relatively short legs.

The present distribution of the leopard is restricted to Asia Minor, India, Southeast Asia, the Himalayas, Tibet, China, Siberia, and Africa. Fossils of leopards were found in Pleistocene deposits throughout Europe, the Middle East, Java, and Africa, some 1.5 million years old, indicating the leopard arrived after the tiger. These secretive cats are mainly nocturnal but in some localities, they are active in the day too. Their populations and ranges are difficult to determine but radio tracking of collared animals has shed new light on their movements and areas they live in.

Black leopard camera trapped in Kaeng Krachan

The leopard is a member of the Felidae family and is the smallest of the four “big cats” in the genus Panthera, or roaring cats. The other three are the tiger, lion and jaguar. The leopard’s range of distribution has decreased radically because of hunting and loss of habitat. It is now chiefly found in sub-Saharan Africa; there are also fragmented populations in Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Indochina, Malaysia, and China. Because of its declining range and population, it is listed as a “Near Threatened” species by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature).

The species’ success in the wild is in part due to its opportunistic hunting behavior, its adaptability to habitats, human settlements and activity, its ability to run at speeds approaching 58 kilometers per hour (36 mph), its unequaled ability to climb trees even when carrying a heavy carcass, and its notorious ability for stealth. The leopard consumes virtually any animal it can hunt down and catch. Its habitat ranges from rainforest to desert terrains.

Wild Water Buffalo – Part One

WILD SPECIES REPORT: The last wild herd in Thailand

Massive beasts with a mean temperament

Young buffalo bull locked onto my boat-blind

Coincidence, according to the dictionary, is the occurrence of two events at the same time. I guess the following story would be seen by most as just that. However, I personally believe that good things come our way after we have made merit.

Such was the case when I showed up with a bag of rice at Huai Mae Dee, a ranger station in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in March of 2007. My longtime friend and chief of the station at the time, Khun Fern, accepted the rice, saying we would cook it in the morning and make an offering to some monks. I agreed and retired for the evening in my comfortable hammock. The weather was cool and I slept well after the long drive from Bangkok.

Up at six, the food was prepared and we both eagerly waited. After a short while, the holy man arrived with some of his followers. We filled their alms bowls with rice and curry. I gave a Thai version of my second book Thailand’s Natural Heritage to the abbot of the temple, hoping it would help the local people around to understand more about Mother Nature. Feeling good at having made merit, I packed up and headed south to where the wild water buffalo live.

Old buffalo bull by the river

After more then three hours of grueling off-road driving, a forest ranger and I set-up camp by the lower Huai Kha Khaeng about mid-day. We had lunch and put my boat-blind together. I then motored upriver for several hours. On the way, I observed some smooth-coated otters hunting along the shoreline but these carnivores quickly disappeared after seeing the boat.

About 4pm as I rounded a bend, a small group of wild water buffalo cooling off in the river actually surprised me and I hesitated for a few seconds locked-on to the herd. About the same moment, I heard a national parks helicopter in the distance out on patrol and it was headed my way so I quickly gunned the electric trolling motor to get closer to the herbivores not thinking there was any danger.

When I was about 50 meters away, I started shooting my camera knowing the helicopter would certainly spook the buffalo. Nonetheless, I noticed a young bull in the herd staring directly at me. He moved up the shoreline followed by a larger cow and the rest of the herd galloping towards the boat-blind. I just kept firing away until my heart shuddered – as I finally realized I was being charged. I suddenly made a gut-wrenching effort to motor the boat out of harm’s way, just as the noisy helicopter hovered overhead. After a few seconds, I looked back and the buffalo were gone.

Buffalo cow charging my boat-blind

Had I been saved by the arrival of the mechanical flying bird – or was it the spirits of the forest that caused such a coincidence and protected me? I will never know how close I came to an attack by the aggressive buffalo, but these photographs are some of the most exciting I have taken as a wildlife photographer. A month later, I photographed a herd of wild elephants in the river not far from the same site. There were a few tense moments with baby elephants in the family unit. My camouflaged boat-blind has definitely paid for itself.

The most gratifying thing was seeing these rare beasts and catching them on digital. There are only 50 individuals surviving in the sanctuary and they can be tough to see and photograph. But it was not the first or the last time I would bump into wild water buffalo. During the late 1990s’ while I was still shooting film and working in Huai Kha Khaeng at the southern area, I managed to get some good shots of a herd wallowing in the river.

Buffalo bull, a purple heron and several pond herons

Journey through a World Heritage Site: Part Six

Day 7: March 10th – Conclusion: World Heritage in jeopardy

Indochinese tiger at a mineral deposit

After all the dust had settled, I can look back at the situation in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary and honestly make an assessment of how and why this World Heritage Site is in jeopardy.

After hearing about three tigers (mother and her cubs) killed by poisoning, it seems poachers continue to enter this place and kill wild animals in the interior. A serious look at the ranger force and patrolling regimens, and the quality of protection is quickly needed before it is too late.

Deciduous forest abstract

For all the research going on in Huai Kha Khaeng, and the so-called smart patrols, how can poachers kill these rare cats? Other reports that wildlife snares and pipe-guns with trip wires are now found outside the headquarters area in Uthai Thani are alarming. These illegal hunters are slipping through the net so to speak due to too many loopholes in the patrolling and enforcement system.

In India several years ago, two national parks where researchers were working full-time had all their tigers exterminated in a year or so right under their noses. Good patrolling and enforcement is the only option when it comes to protected areas.

Deciduous flowers

Here in Thailand, most of the forest rangers are locals and hence there are not many secrets outside the sanctuary. There are 19 ranger stations that receive money amounting to 1,200 baht cash per patrol for food from the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) who also run the ranger-patrolling program. It would seem that food, clothing and equipment would be better than cash that can possibly go astray.

Approximately two times a month a patrol of five or six men spend a week walking the forests on designated trails. The poachers easily stay out of their way because they know the terrain and continue to do business as usual. It is said a bag of tiger bones now fetches more than a hundred thousand baht. Seems like a great incentive to break the law.

All patrols should originate at the headquarters and nobody knows where they are going or what trail they will take until they are already in the forest to keep leaks to a minimum. Patrol groups should be in the forest 24-7 and continue to revolve so that rangers are always out in the field.

Seub Nakhasathien monument

Without a doubt, new blood in the form of properly trained and sufficiently paid rangers using special-forces techniques is seriously needed in Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai Naresuan next door. Enforcement and arrests of perpetrators should increase and outdated laws up-graded with severe fines and detention, especially for repeat offenders.

Another very important issue is life and health insurance for the rangers in case someone is injured or killed while on duty, and this should be standard for everyone, whether government officer, or permanent and temporary rangers. A central fund should be established for this and in case of a tragedy or accident; the family will be taken care of.

Protection of this World Heritage Site is a number one priority for the government, and everything else should be second. Over the long run, good management, patrolling and enforcement is the only option to save Thailand’s natural heritage for the future.

Journey through a World Heritage Site – Part Five

Day 6: March 9th – Wild pig again, and a herd of banteng and a tuskless bull elephant pose for the camera

After breakfast, I drove a kilometer with a forest ranger in tow to look after me and parked in the forest. I thenwalked for a half hour to Huai Mae Dee, a tributary of the Huai Kha Khaeng. A permanent photo-blind is erected across from a mineral lick, also visited by all the large mammals.

After an hour and slightly down stream, a single wild pig was having a great time wallowing in the mud by the bank in the mid-day heat. After awhile, this female ungulate got closer as I continued to photograph her. It was the first time I had ever seen a female by herself. Mostly, they are in herds and only the large male boars live solitary lives.

A short time later, a fairly large herd of banteng appeared on a sandbar downstream from the blind. They were just hanging out taking in the sun’s rays and chewing their cud. The cattle then scattered as a huge tuskless bull elephant popped out on the sandbar. He was following a female, probably in heat judging from his actions. The bull did not stay long and actually came up on our side of the river disappearing into the bush, which was a bit unnerving.

At 6pm as darkness fell, our ranger came to help me carry some equipment back actually bumped into the bull elephant but it went crashing off luckily for us. At close quarters, these old cantankerous giants can be extremely dangerous to people and in fact two persons including a ranger and a villager have recently been killed by a tuskless bull in the sanctuary not far from the headquarters. It pays to stay out of their way.

Journey through a World Heritage Site – Part Four

Day 5: March 8th – Waiting on the helicopter

The next morning up at the crack of dawn, I decided to sit in the blind one last time before departing sometime in the afternoon. After an hour, a lone female green peafowl wandered into the mineral lick pecking on the ground for food and coming quite close. A short time later, a little egret also looking for food in the pond was attacked by a changeable hawk-eagle that swooped down from the trees above grabbing and knocking the water bird off its feet. The raptor hung on finally killing the egret. It was all over in a matter of minutes and the bird of prey began feeding.

Finally, the noisy chopper arrived and we piled aboard for the 20- minute ride to the headquarters. Shortly after arriving, we had lunch, and I decided to drive a hundred kilometers south and then west to Khao Ban Dai ranger station that had been our original destination for this trip.

I left after lunch and then stopped at Ban Rai, Uthai Thani for some provisions arriving at the station just as the sun was setting in the west. Dinner was made up of ‘French toast’, a specialty of mine when a quick easy meal is sufficient. Eggs, milk and some whole wheat bread make up the ingredients. The night was cool as I both slept like a log in my hammock.

Journey through a World Heritage Site – Part Three

Day 3: March 7th – Hot trek over the hills

Like clockwork, first light eventually came and after a quick cup of coffee and some breakfast, everyone packed-up their gear and headed out to beat the sun. But it was scorching hot by 10am and the dusty trail went up and down and was long as we threaded our way over the hills on a wildlife trail trodden by elephant and other large animals for millennia.

At lunch, a quick camp was erected down at the river as we all cooled off and enjoyed the refreshing water. An hour later, it was up into the hills again. The rangers attached to me got sidetracked and led us down off trail getting lost for a short period until I headed back up and found the right route. From there, we discovered a pile of gaur bones that had certainly been poached for its horns. Continuing on, we trudged along the path until the late afternoon finally reaching our number one objective as the sun dipped low.

Two large mineral licks situated by the river on either side where large mammals like gaur, banteng and elephant come for the mineral supplements. A set of fresh tiger tracks was discovered on the trail down to the deposit. The rangers quickly set-up a photographic blind in the mineral licks for me as we settled in by the river. Promptly, dinner was served and it was a quick dash to bed for most of the group after the long hot day. The excitement of finally sitting at a mineral lick I had never visited kept me up for awhile as I lay in the hammock.

Day 4: March 8th – Pigeons, parrots, and another wild pig

After that, the day passed slowly and about 4pm, a huge wild boar came to wallow in the mud and take in some vegetation staying for quite sometime. I snapped a long series of photos of the solitary pig. The rest of the day was quiet and we finally retired to the camp just before darkness.

That evening, a decision to cancel the rest of the trip was reached, and to take us by helicopter back to the headquarters due to several issues involving tiger poachers plus the extreme conditions of heat. Three tigers (a mother and two cubs) were found dead from poisoning not to far from our position. Illegal tiger bone hunters were operating in the area and the chief decided to move the group expediently away for our safety as a first priority. In the past, many rangers have been killed or maimed by ruthless poachers. Unfortunately, we would not make our destination down the river but the option to drive there was still open.

Journey through a World Heritage Site – Part Two

On the road to Huai Kha Khaeng

Seub Nakhasatien monument

Day one: March 5th

I left Bangkok slightly behind schedule but made good time as I headed northwest. After five hours of driving with a few pit stops here and there to eat, buy fuel, food and essentials, I arrived at the headquarters of Huai Kha Khaeng. As always, I paid respects to Seub Nakhasatien, a forest ranger who gave his life to nature back in 1990. This site is his spiritual home and many people visit his statue and the house where he lived, in remembrance of his sacrifice. While we were at the headquarters, I photographed a few Eld’s deer that were released into the wild around the station.

Wild boar on the run at a mineral deposit

I then drove another couple of hours going south for a rendezvous at Khao Nang Ram Wildlife Research Station. As I got closer, a huge wild boar flashed across the dirt road and disappeared into the forest giving us a bit of jolt. A total of eight forest guards including the assistant chief graciously welcomed me providing shelter and dinner. I arrived just at dusk and handed over the provisions for the excursion down the river. Dinner was served and we then watched a documentary showing wildlife and tiger research carried out at the station. Everyone retired to bed for an early wake-up.

A racket-tailed drongo by the river

Day two: March 6th – A change of plans

Our original plan was to walk from the research station across the mountains and down to the river but due to extremely hot and dry conditions in the mixed deciduous forest and the possibility of forest fire, it was decided to drive further north to the river and walk from an old deserted ranger station named ‘Yang Dang’ so we would have a good supply of water the entire length of the walk. I brought a water purification pump and we always had clean safe drinking water. This tool was simple to use and carry but extremely important for us city folk accustomed to bottled water.

Through the forest we continued west and arrived at Kabook Kabieng ranger station some 50 kilometers north. During the dry season, this part of the forest in Huai Kha Khaeng is still lush hill-evergreen. For me, this place has many fond memories of great photographic sessions.

Another wild boar at another mineral deposit

I got my first ever camera-trap photograph of a leopard on a deer kill very close to the station. On that same trip, I also photographed another leopard along the road in late afternoon from my truck, and captured a shot of a black leopard from a tree-blind at a nearby hot spring the next day. I got three leopards in two days and it still stands out as one of my great achievements as a wildlife photographer. Leopards are notoriously difficult to see and it was a lucky trip.

A black leopard photographed more than ten years ago at a hot spring

Finally, we all arrived at ‘Yang Dang’ and made preparations for the 30-kilometer trip down river. The road was rough on my old Ford Ranger but we chugged along in low gear for some gut-wrenching 4X4 driving. Unfortunately, a carry rack on top of the cab was ripped off and destroyed during the rough and tumble, and reduced to rubble.

Everyone packed up and off we went down the river. We still had to negotiate about 6 kilometers on foot to the first camp during mid-day temperatures that went past 38 degrees centigrade. It was a struggle but we made it and set-up camp by the peaceful Huai Kha Khaeng waterway just as the sun dipped behind the mountains. The water was extremely cool and it was great having a bath and freshening up for the first night by the river. Dinner was served in typical jungle style with rice cooked in army patrol pots and various Thai dishes including some hot curry. Everyone then hit their beds and sleep quickly overcame the group.

Journey through a World Heritage Site – Part One

Journey through a World Heritage Site: Part One

Hot days, rough terrain and wild pigs galore. Thailand’s last great tiger haven

Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary situated in the provinces of Uthai Thani, Tak, Kanchanaburi and Suphan Buri is Thailand’s last great tiger haven. The protected area covers 2,780 square kilometers, and a seasonal river runs through the center of the sanctuary from north to south with many tributaries along its path. During March, the waterway is low but still flowing for most of its length. In some areas however, the sandy river bottom dries up. The weather is very hot during the day with temperatures soaring above 38 degrees centigrade.

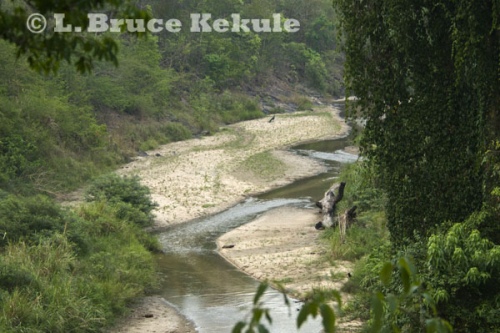

Huai Kha Khaeng riverine habitat

An old dream of mine was to walk the river from north to south and experience this majestic animal kingdom first hand. I met with the Director General of the Department of National Parks at the time, Jatuporn Buruspat, to coordinate all logistics for the trip. The plan was to walk from Khao Nang Ram Wildlife Research Station in the eastern section to Khao Ban Dai ranger station in the central part, a distance of about 30 kilometers. It was expected to take about seven days with several stops along the way at a few mineral deposits, hopefully to photograph wildlife.

My trip began on March 5th and left Bangkok first thing in the morning driving some 300 kilometers diagonally across Thailand going northwest. I passed through the very modern city of Suphan Buri with its excellent roads and modern facilities. My final destination is the Huai Kha Khaeng headquarters area situated in the western forests of Uthai Thani province. The deciduous and hill evergreen forest found in the interior still harbor large herds of elephant, gaur, banteng, sambar and wild pig, plus the amazing carnivores, the tiger and leopard in fair numbers. As a World Heritage Site, it truly lives up to its name as Thailand’s top protected area.

Huai Kha Khaeng forest from a helicopter

Gaur – Majestic Wild Forest Ox

WILD SPECIES REPORT

Rare mammal and the largest bovid in the world

Endangered wild cattle close to extinction

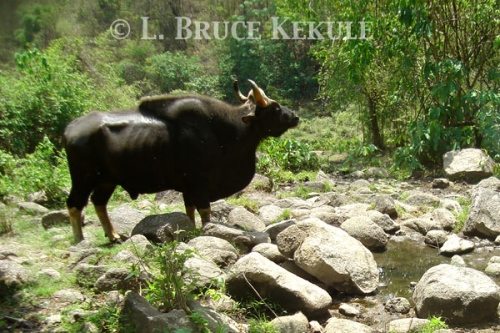

Gaur cow in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

About 20 million years ago, the first ungulates evolved from small, hornless deer-like ancestors. Cattle, sheep, antelopes and goats are grouped together in the family Bovidae, and the most common hoofed grazing animal seen today. Sometime during the Pleistocene Epoch 1.8 million years ago, the genus Bos evolved in Asia and spread to Europe, Africa and eventually North America. Gaur Bos gaurus is a descendent of Bos Bibos, a wild cattle that lived on the great plains of Asia. Saber-toothed cats were one of the top carnivores at the time, and evolved alongside the ancient herbivores.

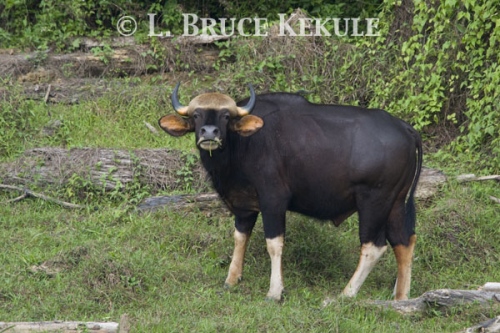

Gaur calf in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

Gaur, the largest bovid in the world, is threatened with extinction and deserves much greater attention. The tiger and elephant have taken most of the conservation spotlight but gaur, like all the other wild animals need just as much protection, research and concern. Unfortunately, these wild forest ox continue to vanish from the wilderness areas in the Kingdom. After years of poor protective management and neglect, poaching and trophy hunting, plus a disappearing habitat suitable for these enormous creatures once found throughout Thailand, is the main reason for the decline.

Over their entire range, they are classified as internationally threatened. But not all is lost as gaur still survive quite well in a few of Thailand’s top protected areas in fair numbers, and where there are true safe havens, the species has actually made a come back. It is now estimated that more than a 1,000 individuals remain in Thai forests. This number is up from the 500 recorded in Dr Boonsong Legakul and Jeffery McNeeley’s book Mammals of Thailand published in 1977. Dr Sompoad Srikosamatara and Varavudh Suteethorn published a paper in the Siam Society’s Natural History Bulletin in 1995 about gaur and banteng. Their estimate then was about 1000 gaur were surviving so the number is basically stable and most likely on the increase.

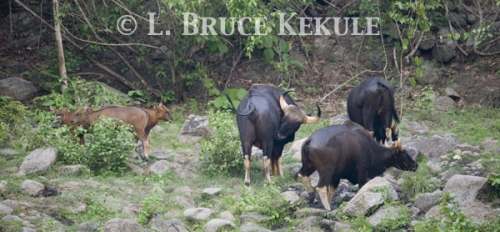

Gaur herd at a mineral deposit in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary

In Southeast Asia and India, gaur is found in scattered and splintered habitats. Other large wild bovine are banteng and wild water buffalo of Southeast and Southern Asia, the yak of Central Asia, the cape buffalo of Africa, and the bison of North America and Europe. In recent times, the number of these wild creatures has dwindled as humans continue to hunt them for meat and trophies, and destroy and encroach on their habitat in some places. The American bison came close to extinction but was saved in the nick of time. Thousands of wild bison now survive due to conservation efforts initiated by many people including the late U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt.

Gaur is Thailand’s second largest terrestrial animal after the elephant and tends to inhibit deep mountainous terrain far from humans. They survive in dry and moist evergreen forest plus mixed deciduous forests and therefore, have fared better than their cousin, the banteng that live in more open lowland forest. Gaur occasionally mixes with banteng that has been documented in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, Uthai Thani province. Gaur will also shadow elephant herds using the same trails made by the larger mammals.

Gaur herd in Khlong Saeng

My favorite photographic wildlife subject is gaur. In Thailand, these majestic ungulates can still be found in the following places: the Western Forest Complex and Kaeng Krachan Forest Complex, both in the west; the Khao Ang Rue Nai Forest Complex in the east; the Dong Payayen – Khao Yai Forest Complex and the Phu Khieo – Nam Nao Forest Complex, both in the Northeast; and down south in the Khlong Saeng – Khao Sok Forest Complex. Due to the serious instability in the deep south, very few surveys have been carried out and there is no consensus on gaur but they do survive in the Hala-Bala Forest Complex situated along the border with Malaysia. It is doubtful if any gaur survive in the North but the Omkoi – Mae Tuen Forest Complex might have few left.

Gaur has a keen sense of smell and hearing, and is always alert for danger. As a result, they can be tough to spot in the dense forests of Asia. However, luck does come sometimes, and the following accounts describe the few times I have had the great fortune to observe these magnificent beasts in the wild.

Gaur bull camera-trapped at a mineral lick in Huai Kha Khaeng

My first photographic encounter with gaur in 1986 was at the beginning of my career as a wildlife photographer deep in the interior of Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. A natural deposit or mineral lick several hours walk from the road attracts many animals – gaur, banteng, elephant, sambar and muntjac come for the life-giving minerals, plus tiger, leopard and Asian wild dog hunt for prey. The balance of nature runs in harmony where “eat or be eaten” is the rule. I was extremely lucky and photographed two mature bull gaur that arrived late one afternoon as the sun was setting. The old bull on the front cover of my first book ‘Wildlife in the Kingdom of Thailand’ stayed at the waterhole for quite sometime and I shot several rolls of film. This place has always been special to me.

A year later, I began visiting Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary along the western border with Burma specifically to photograph gaur. In 1985, a herd of more than 50 individuals was seen from a helicopter by park officials on the huge grassland in the center of the sanctuary. Thung Yai is a tough place to work as many mining trucks plus off-road 4X4 enthusiasts with big tires and jacked-up truck chassis have abused the road into the sanctuary for many years. Deep ruts in many areas make travel along the road difficult even for normal off-road vehicles. The rangers have a real rough time patrolling this sanctuary.

Young gaur bull in Khlong Saeng

On one of my many trips to Thung Yai, and after many grueling hours of travel, and then a couple hours’ walk to a mineral lick in the sanctuary, I set-up a photographic blind along the forest perimeter. Late in the afternoon, two bachelor bulls entered and drank from the spring at the top end. I managed to get some good photographs as they went about their business. One bull snorted at our position as I had placed fresh gaur droppings in front of the blind, and I believe he was just letting us know who he was. Both bulls then departed peacefully and I was elated to say the least. It is estimated that more than 100 individuals thrive in Thung Yai.

In October 2008, I began a camera-trap program and set several units at a mineral lick visited by gaur and elephant in Kaeng Krachan National Park in Phetchaburi province, southwest Thailand. A month later, I visited the park and collected the cameras. A herd of gaur had come to the deposit including several cows and their offspring. It seemed as if the camera had spooked them initially, but the herd came back again the next day and a long series of captures was obtained. There are about 70 of these beautiful creatures thriving and breeding in this protected area.

Over in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in the west during December 2008, I also set some digital camera-traps at a water hole, and after one month, two gaur bulls visited the waterhole. I also sat by the river in a photo-blind across from another mineral lick and photographed a large herd of gaur that had come for the minerals and lush grass. It is estimated that 350 gaur survive in this sanctuary. Better protective measures have allowed gaur to breed profusely and this World Heritage Site lives up to its name. Predators like tiger and wild dogs capable of taking on gaur, also thrive here. In the whole of the Western Forest Complex, it is estimated that more than 500 individuals live in scattered areas covering some 15,000 square kilometers.

Gaur cow camera-trapped at a mineral lick in Kaeng Krachan National Park

Early this year while photographing wildlife in Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Surat Thani province down south, I had an amazing journey of discovery. Deep in the protected area, gaur is still thriving quite well. I set camera-traps in the sanctuary and managed to capture a very old bull gaur and several herds at many locations. A close look at the photograph shows seriously worn hooves on his hind feet. He is definitely past his prime and would not be a contender for female gaur in heat. With poor traction, he could not fight the younger bulls with stronger hooves and horns.

I also toured the flooded forests of Khlong Saeng and Khlong Ya rivers created by the Chiew Larn or Ratchaprapra Dam using a boat-blind and silent electric trolling motor. I was able to approach many herds and individuals over a four-month period. In every herd, there were young calves and yearlings indicating a healthy breeding population. Most of the mature bulls have become nocturnal due to past and present poaching pressure in the reservoir. In the Khlong Saeng – Khao Sok forest complex, it is estimated that more than 100 gaur are thriving.

In Kui Buri National Park, Prachuap Kirikan province, gaur has definitely made a come back due to increased awareness by the park staff plus financial support extended to help the rangers. It is now estimated that the population of gaur is about 70 individuals. Khun Chalerm Yoovidhya, MD of the Huai Hin Hills Vineyard and Siam Winery has taken a special interest in gaur at Kui Buri. Working with the park officials, he has funded many projects to help these creatures by sending volunteers to plant grass in selected areas to propagate grasslands, and setting up salt licks and check dams to attract the herbivores. Other projects initiated by Khun Chalerm include selling wildlife photographs and paintings at the vineyard to help the park rangers with food, clothing and equipment giving them more incentive to patrol the forest. Over time, other areas will put on the list for special help to protect Thailand’s natural heritage from the damaging effect of human poaching and intervention.

Gaur spooked by camera-trap in Kaeng Krachan

In the northwest section of Thap Lan National Park, my very close friend Gate Glomchum who worked for the Petroleum Authority of Thailand (PTT) as chief reforestation officer (retired) did some amazing things during his career as a reforester. Prior to 1996, a 10,000 rai area in Wang Nam Kheaw was completed degraded by a logging concession and squatters. Under his management and following a mandate set by His Majesty the King, this forest was replanted and the people were moved out. Today, this forest has completely grown-over, and there is elephant, gaur and tiger plus many other classic Asian species living in total harmony with nature. Other areas in Thailand also reforested under his supervision have had similar success.

Over in Khao Phang Ma just outside the eastern part of Khao Yai National Park, a national forest reserve was reforested by Wildlife Fund Thailand (WFT) and Khun Suthirat Yoovidhya (Director of CSR) of Red Bull-Thailand fame. Gaur moved back into this forest from Khao Yai after protective measures increased. There are about 50 gaur at this location and is probably the only place in Thailand where gaur live outside a protected area. Many projects like helping the rangers, setting-up salt licks and check dams have also been funded by Khun Suthirat under the ‘Red Bull Spirit’ program that is on-going. A couple of years ago, WFT shutdown all conservation operations due to internal conflicts but the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP) took over responsibility of the reserve. They should be commended, and it is reassuring that some people are serious about conserving the Kingdom’s natural heritage.

Gaur herd camera-trapped at a mineral lick in Kaeng Krachan

In the long run, the importance of protecting a prey species like gaur should be the number one priority for the government. The DNP need to increase budgets and personnel to look after these forests and animals. Thailand remains one of the best places for the survival of gaur in Southeast Asia. Protection, conservation awareness, education and monetary support are the keys to the future of these magnificent creatures of nature, and it is hoped they will continue to live in their natural habitat far from the destructive forces of man.

Ecology and Behavior

Gaur is the largest bovid in the world with a distinctive dorsal ridge and a large dewlap, forming a very powerful appearance. A fully mature bull stands about 1.6-1.9 meters at the shoulder and average weight of a big bull is 900 kilograms on up to a ton. Cows are only about 10cm shorter in height, but are more lightly built and weigh 150 kilograms less. These even-toed ungulates have stout limbs with white or yellow stockings from the knee to the hoof. The tail is long and the tip is tufted. Newborns are a light golden color, but soon darken to coffee or reddish brown. Old bulls and cows are jet black but south of the Istamas of Kra, many take on a reddish hue.

All bovine share common features, such as strong defensive horns that never shed on males and females, as well as teeth and four-chambered stomachs adapted for chewing and digesting grass. Their long legs and two-toed feet are designed for fast running and agile leaping to escape predators. They are gregarious animals, staying in herds of six to 20, or more.

Due to their formidable size and power, gaur has few natural enemies. Leopards and Asian wild dog packs occasionally attack unguarded calves or unhealthy animals, but only the tiger has been reported to kill a full-grown adult. Gaur grazes on grass but also browse edible shrubs, leaves and fallen fruit, and usually feed through the night. They also visit mineral licks to supplement their diet. During the day, they will rest-up in deep shade.

There are three separate sub-species of gaur: Bos gaurus gaurus of India and Nepal, Bos gaurus readi of Indochina and Bos gaurus hubbacki of Southern Thailand and Malaysia. However, in 1983, the zoological classification of both the Indochinese and Southern gaur was changed to Bos gaurus laosiensis. In 1993, Pleistocene fossil evidence of Bos gaurus grangeri, an ancient sub-species, was uncovered by G.B. Corbet and J.E. Hill in Sichuan province, China.